Artist Billy Al Bengston packs quite a wallop in his slight 83-year-old frame. One of his best friends is architect Frank Gehry, who, like Bengston, came west to ply his avant-garde craft at a time when design, art and culture was rigid and uptight. Bengston was a motorcycle racer, and his abstract approach to art attracted other like-minded characters in `60s southern California, where Bengston has called home ever since, specifically Venice. Actor and director Dennis Hopper, portrait artist Don Bachardy and his partner—the novelist Christopher Ishwerwood—blended cultures and influences that still resonate decades later.Photos: Billy Al Bengston

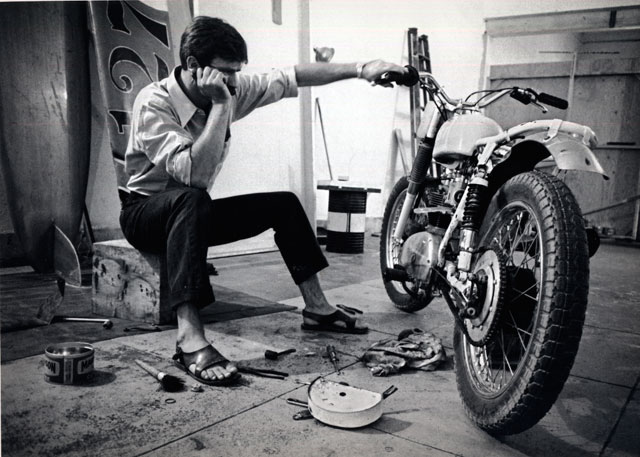

In the early ’60s, Bengston began racing motorcycles professionally; he found inspiration in the bikes, incorporating them as a subject. At the same time, Bengston made his name in the art scene by using lacquered auto paint to create high-gloss geometric and abstract forms on metals and canvases, using the chevron and iris as his calling cards. “Both racing and art take tenacity, talent, hard work, knowledge and skill,” he said in a 2004 interview.

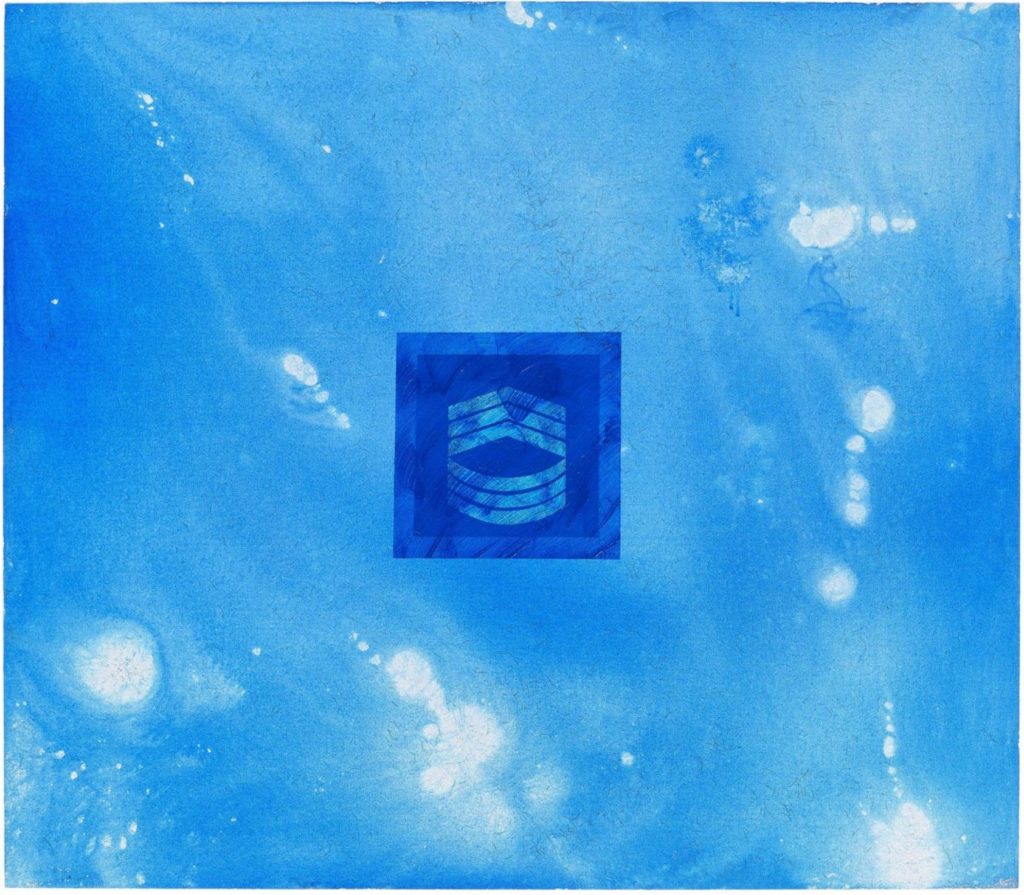

In October 2016, Bengston had a showing at VENUS Over Manhattan gallery on Madison Avenue in New York, where he presented his B.S.A. Motorcycle Series, (1961), 12 paintings originally shown at Ferus gallery on North La Cienega Boulevard in Los Angeles in 1961, in addition to new blue monochromes dedicated to Aub LeBard, an off-road motorcycle racer, and co-owner of the LeBard & Underwood motorcycle shop, Bengston’s first sponsor. “I went to Europe in 1958, and rode all around on a Lambretta,” Bengston said in an interview with Jennifer Samet. “I returned to New York, waiting for my scooter to come. It finally came, but they managed to drop it off the van, and bend the front forks. I sent it back to California but I couldn’t get anyone to fix it. “I called around and finally talked to the LeBard shop. Even though they were a B.S.A. motorcycle shop, they agreed to fix it. I so admired the motorcycle racers and the people. I said, ‘I have got to get into this.’ It was a thrill and a half. Aub LeBard was an inspiration and later became my sponsor.

“Racing motorcycles was supposed to be the most dangerous thing you could do,” Bengston said. “So I did it to make a living. I did stunts in movies, too. I had done gymnastics training. I always tried to take a job that would pay the most for the least amount of time, so that I could go back to work quickly. I could jump off a building and make enough to live for a month, without even thinking about it. Sometimes it would be enough to live for three or four months—rent and food.” Bengston’s grit came from his pursuit of a handmade world, one where he determined his vocation and destiny. Thank God it included motorcycles. “I do what I do,” Bengston added. “I have no fucking idea why. When I painted these motorcycle paintings, I pissed people off beyond belief. I don’t know why. They’re just paintings. You don’t have to look at them. Whenever I get in trouble, I quote Ken. He said, `The only thing you have to do to outrage people is anything.’ Throughout his career he’s ebbed and flowed with monochromatic paintings, which he says is somewhat of an inside joke. His 2016 show included a motorcycle he raced, which he got from Aub’s shop.

“At the time, I told him, ‘I’m going to paint this motorcycle.’” Aub said, `You can paint it any color you want to, as long as it’s blue.’ Everything he owned was blue. It’s a challenge to do everything in monochrome. You have to do a lot with textural variation—thin and thick paint. You remove highlights so you have to build highlights. You remove the center of interest, so you have to build center of interest. They’re all built differently.” Bengston also thinks inspiration comes and goes, but is never eternal, and rarely replicated.

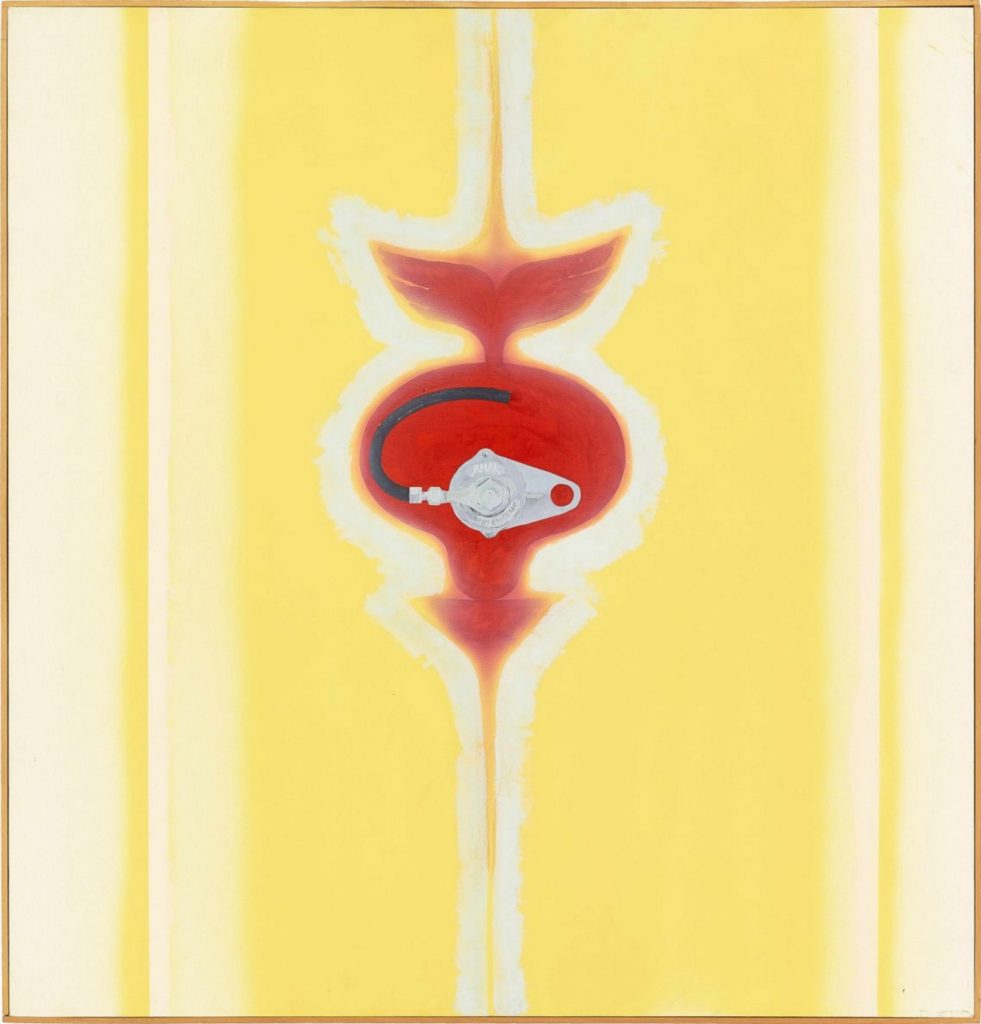

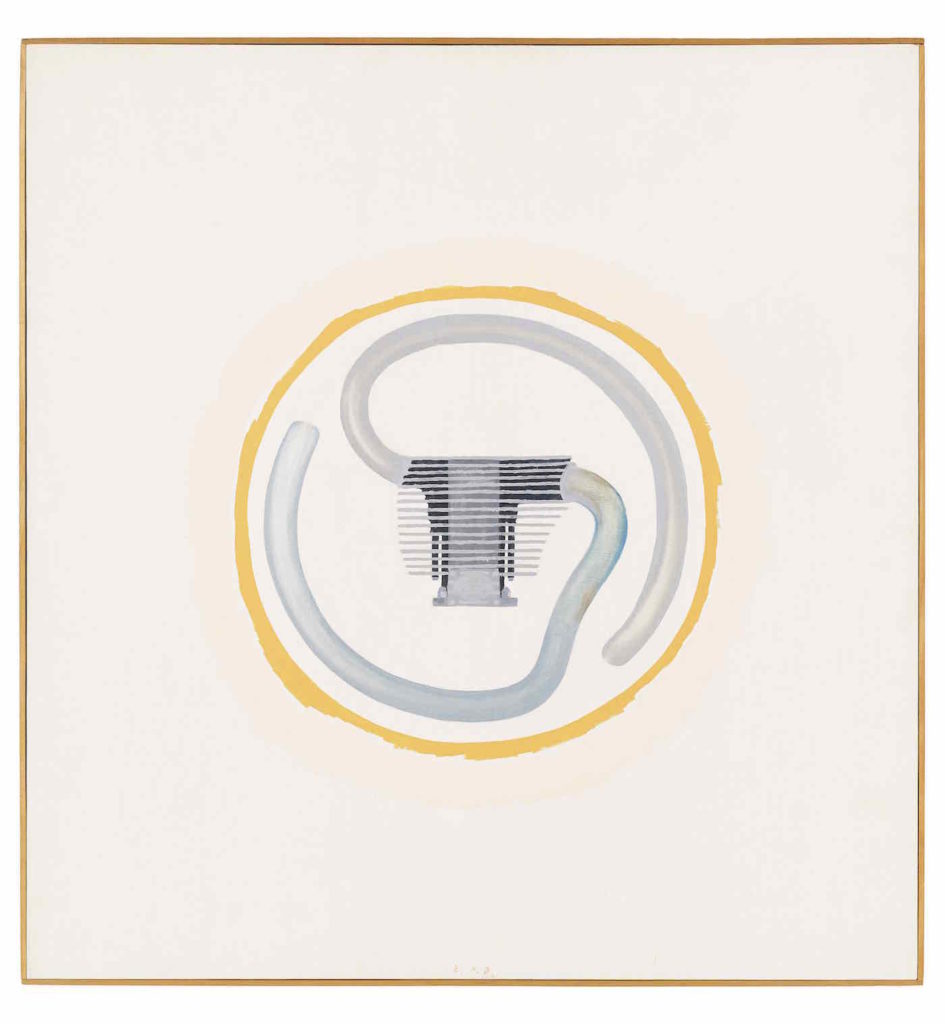

“The painting Ideal Exhaust (1961) is so naïve that I could never do it again,” he said. “I couldn’t do it that good. I don’t think there’s anything here I could do again. If you get it real realistic, you can do it again. But if you’re clumsily making it abstract, it’s very hard to repaint. You don’t have the instruments; you don’t think the same way. Your hand works differently.”

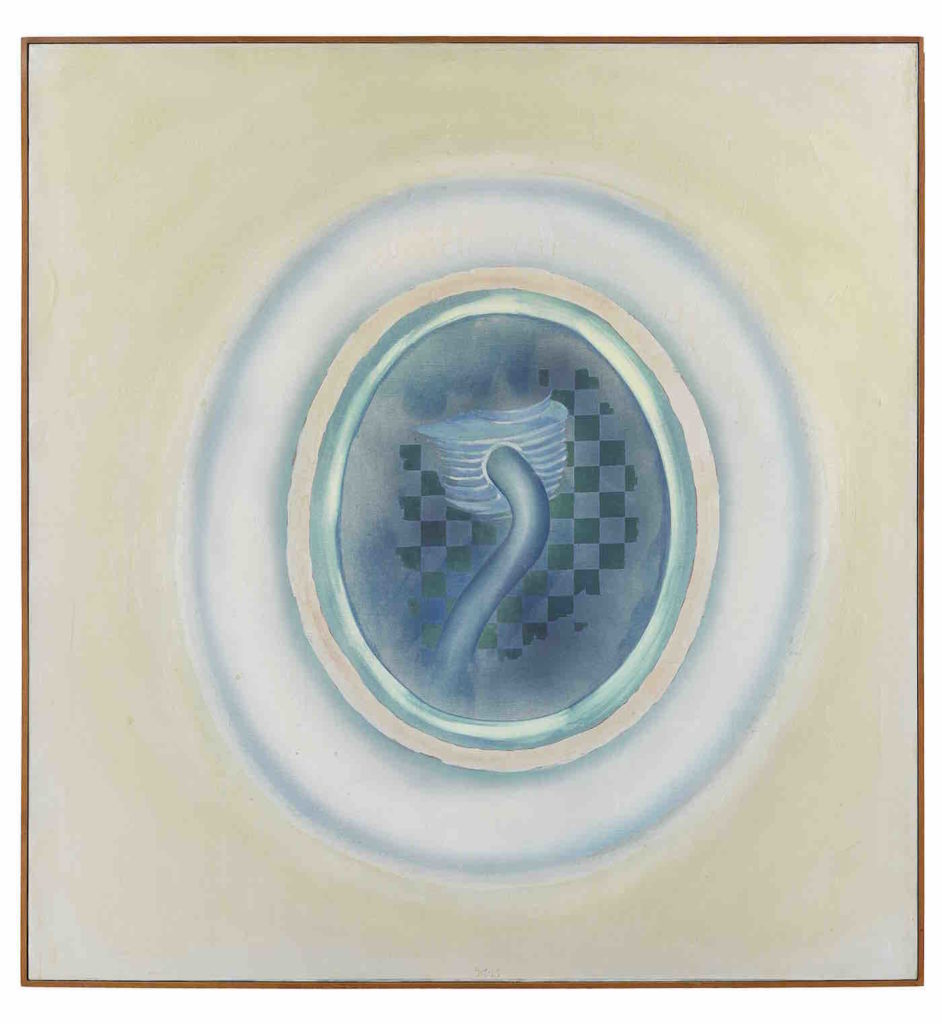

“There are mistakes in that painting that I can’t believe that I made—three or four things I could point out, but I won’t. If you look at Barrel & Exhaust Pipe (1961), the exhaust pipe is incorrectly placed. It don’t look like that. I don’t know why I did it that way. Maybe because I couldn’t do it right, and I thought no one else would know the difference. I’m not really anal compulsive. I sorta like zits sometimes. If you like perfection, it ain’t gonna look perfect later. You’ve gotta learn to love it (or not).”