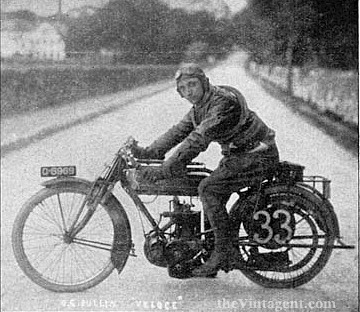

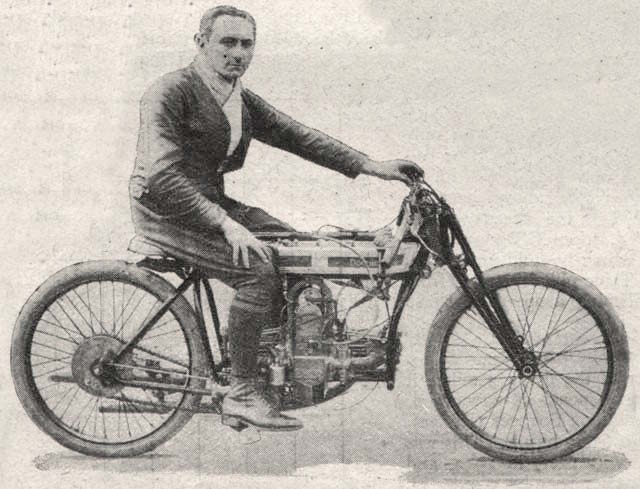

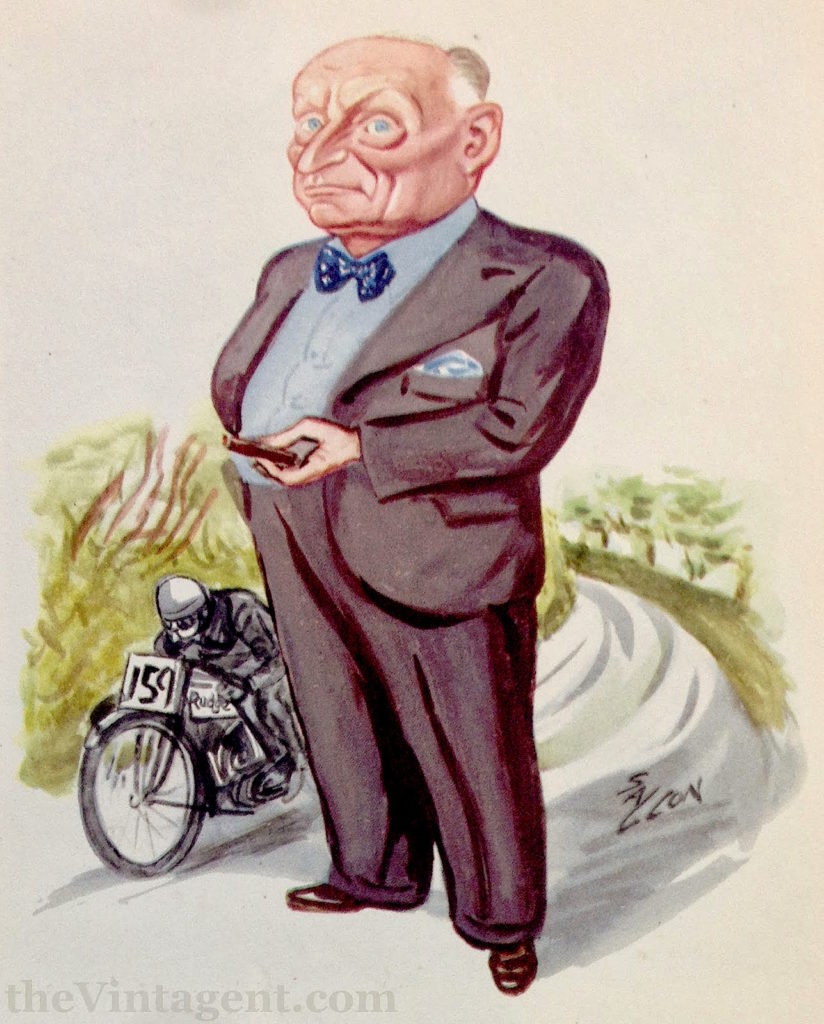

Cyril Pullin was a rare bird among the many fascinating motorcycle inventors of the early 20th Century; while there were many rider-designer-manufacturers during the era, he was in very rare company of men who not only designed, built, and raced motorcycles, but also won an Isle of Man TT race, a distinction he shares only with Howard R Davies (HRD) and Charlie and Harry Collier (Matchless).The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world’s rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

Related Posts

July 27, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 1: Billy Wells

Over 100 years ago, Indian swept the…

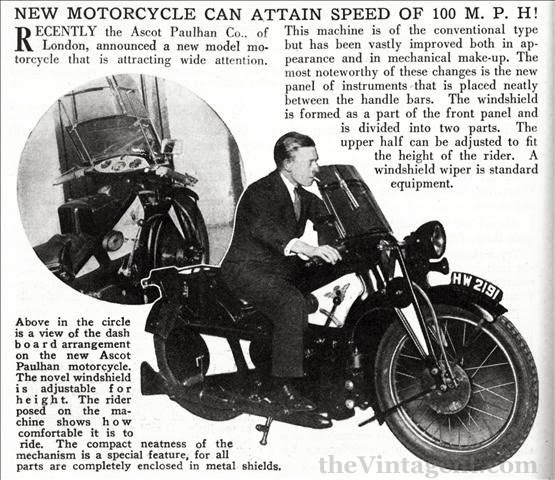

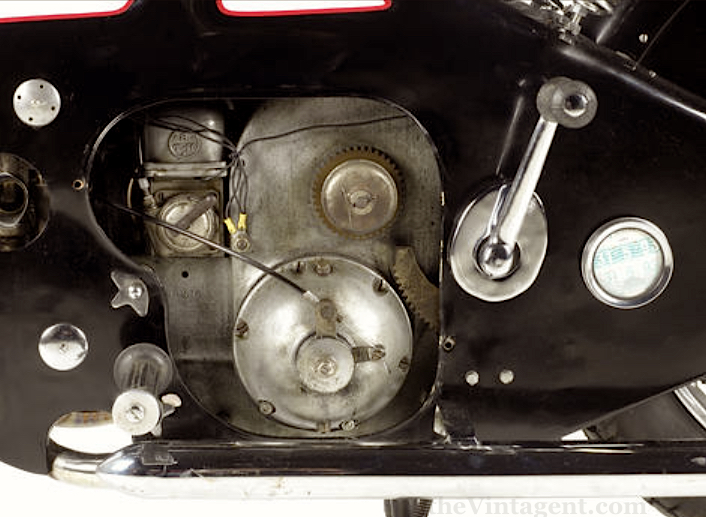

In the book “Behind the scenes in the vintage years”, Arthur Bourne (a.k.a. “Torrens”) comments on testing the Ascot-Pullin. In the original press presentation he tested one of the machines in natty suiting and bowler hat through Regent’s Park. He found the steering poor, the clutch did not free and the gear change was bad. He raised these points and was invited to further testing at the works at Letchwork. He would have lunch with works riders at the George and Dragon Hotel in Baldock and test the machine.

He headed for Great North Road and opened up. Speedometer climbed just over 60 with no more throttle left and Torrens would experience his first tank-slapper. Before falling, he jumped off. He had a heavy coat, but a sparkplug in his pocket hurt him. He jumped up and asked for another machine and continued testing.

He then was told by a friend of a friend that one of the test riders at Letchworth had been admitted at hospital with compound fractures. The test rider some months later would ask Torrens for a job and confirm it was him who had had an accident with the same bike that almost did Torrens himself!

A further test was scheduled at Brooklands. There was a meeting so the gate at the front of the test hill, where he wanted to have some pictures taken, was closed, which forced him to approach the hill from the summit. After the photographs were taken, he tried to restart the engine, the carburetor flooded, the engine backfired and the carburetor caught fire. The machine had no exhaust valve lifter that would allow a kickstart that could kill the fire, so he let it run down to the paddock, where there were fire extinguishers. The machine required a new electrical system.

A last test was scheduled the following Saturday following the West of England Open Trial. The performance was not very good and “Torrens” ended up pushing it up a hill. One further road test would happen on Monday. The mail arrived in the morning and in it was a communication that Ascot-Pullin was going into liquidation.

Cyril Pullin ended up running the George and Dragon hotel in Baldock some time later.

Then I should be called Lucky to have escaped with my skin!

The tragedy of every ‘great idea’ is the capital required to make it work flawlessly. Clearly, the Ascot-Pullin, like so many other small manufacturers, did not have the cash or the time to sort their design properly. Nor did the Majestic, the MGC, the MacEvoy, and a dozen others under the letter ‘M’… and there are 25 letters more to choose from, Ascot-Pullin to Zegemo, all under-funded and short-lived!

Even large factories flub on the ‘rushed development’ score – think of the first oil-in-frame Triumphs of 1971; the first computer-designed motorcycle frame, which had a 33″ seat height when actually built, and the engine didn’t fit! This fiasco took 6 months’ heroic efforts to amend by the factory workers, but the crucial Spring shipment to the USA had been missed, which led directly to the (attempted) shut-down of Triumph in Sept 1973. And the workers’ sit-in which led to the Meriden Co-op – I’ll be writing that story soon!

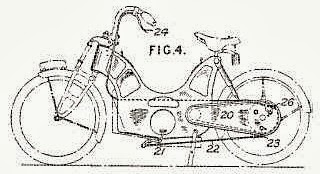

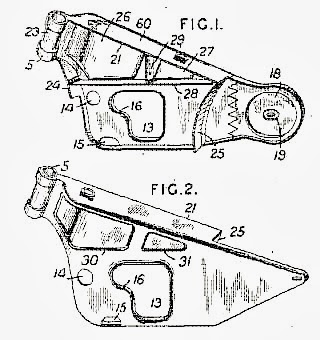

Thank you for this informative article. As a relation of Cyril Pullin, it’s always interesting to read these things! I have a few of his patent files displayed at home too, which I found on eBay.

He was a pivotal character in the British motorcycle industry, and a man full of ideas!

Stanley Groom was my great uncle. He was married to my Great Aunt Andree (maiden name Arnaud.

If anyone has information on Stanley Groom I am very interested. He was an engineer and a founder of what is today known as Carrier Air conditioning. Groom was a close friend of Willis Carrier

If anyone should require a cylinder head for a 500 Ascot-Pullin, I have one!

Now that’s a rare spare!

Cyril Pullin was my grandfathers brother on my mothers side – Alfred Pullin. Up until about 10/15 years ago I was in touch with one of the Bailey family who had some bits and bobs about the Pullins- I had stuff as did he and we swapped. Unfortunately, he used faxes to send me images and print whih have now faded completely so I now have lots of plain fax paper.. Out of interest Fenton Bailey, the grandson is known for creating a number of TV shows including a very different kind of race….Ru Pauls Drag Race!

it would be good to know any more info about Cyril as it would link into the lack of info I have on my grandfather- if any one can point me in the right direction.

I remember seeing one of the Ascot Pullin Motorcycles in the science museum many years ago ( 1970’s) however its no longer there. I have seen the black and white one and know of a red one and a blue one but would be nice to know where the survivors are. i always thought it was a beautiful looking machine and ahead of its time with some great Art Deco styling

Hi Scott,

the only published book is this curious compilation of available articles:

https://www.morebooks.de/shop-ui/shop/product/9786135882476

There’s plenty of info on Cyril in various sources, but no proper book in this interesting character. If you re-connect with your extended family, I’d love to see what they turn up – I can always write another article!