It isn’t an everyday occurrence, finding yourself in a time capsule house in France, looking at a 1940 Triumph Tiger 100, sat parked in a hallway since the 1980s. Prewar T100s are rare — they were rare when new — and given the onset of WW2, 1940 models are very rare indeed. Most were exported to the United States, but a few went elsewhere. This machine in the hallway was ordered new by a Frenchman, who collected it from a Triumph dealer in the northern French town of Amiens, in November 1939.[Words: Prosper Keating]

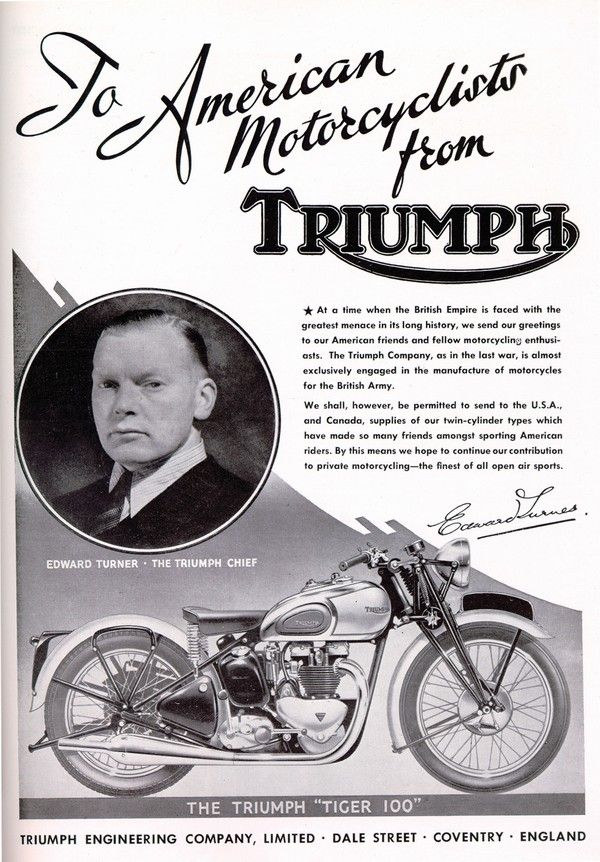

Historians among you will doubtless wonder what kind of nonsense you are reading, given that the British War Department requisitioned all stocks from the largest motorcycle factories, shortly after the declaration of war with Germany – September 3rd 1939. Triumph motorcycles were not exempt… except for the firm’s 500cc parallel twins. They were considered too exotic and high-performance for the armed forces, and no mechanics had yet been trained to work on anything but sidevalve singles. Not only did the military not want the Speed Twins and Tiger 100s, but Triumph was authorised to continue producing and exporting them despite the war, and the governmental interdiction on civilian vehicle production announced in May 1940. Thus in the United States, the late summer and autumn 1940 issues of Motorcyclist magazine carried Triumph advertisements bearing Managing Director Edward Turner’s signature under the following, somewhat Churchillian announcement.

“At a time when the British Empire is faced with the greatest menace in its long history, we send our greetings to our American friends and fellow motorcycling enthusiasts. The Triumph Company, as in the last war, is almost exclusively engaged in the manufacture of motorcycles for the British Army. We shall. however. be permitted to send to the U.S.A., and Canada, supplies of our twin-cylinder types which have made so many friends amongst sporting American riders. By this means we hope to continue out contribution to private motorcycling — the finest of all open air sports.”

By Summer 1940, of course, the Germans were installed in Paris and all along the coast facing Britain, having invaded France and other countries that May. But in November 1939, when ‘our’ Tiger 100 arrived in Amiens, Britain, France and Germany were still engaged in what Germans nicknamed the Sitzkrieg, and the British called ‘The Phoney War’. Lines of communication and trade between Britain and France remained open. Triumph owner Jack Sangster was a powerful businessman, and persuaded his pals in government on the fiscal benefits of permitting his firm to carry on exporting its successful 500cc twins to the all-important US marketplace, where Turner had bolstered Triumph’s presence since 1937. That Triumph was awarded the prestigious Maude’s Trophy in November 1939 surely helped Sangster’s argument.

The Maudes Trophy

In late February 1939, Auto Cycle Union (ACU) officials were invited to choose a random Tiger 100 from any Triumph dealer they wished, and a Speed Twin from any other Triumph dealer. The selected T100 and 5T were registered for the road by the Triumph works as EDU 223 and EDU 224 respectively (EDU being a Coventry registration prefix). To run in the motors, Triumph employees rode the two twins from the factory in Coventry to John O’Groats on the northernmost tip of Britain – around 580 miles. Followed by ACU observers, the Triumphs were then ridden from John O’Groats to Land’s End – Britain’s southernmost point.

The weather conditions in the Scottish Highlands were atrocious, but the riders pressed on with reduced speed, and on reaching Land’s End, they rode to Brooklands. There two experienced Brooklands Boys took the handlebars, and rode the Triumphs at high speed around that banked autodrome for six hours. The Tiger 100 and Speed Twin were then ridden back to the works in Coventry, and stripped for inspection under ACU observation. Negligible wear was found in the motors. The road route of over 1,800 miles was covered at an average speed of 42 mph. At Brooklands, the T100 averaged 78.5 mph with a best lap of 88.46 mph and the Speed Twin was not much slower at an average of 75.02 mph and a best lap of 84.41 mph. Apart from two flat tires and one of the machines falling over whilst parked on its stand, the riders encountered no problems, and Triumph was awarded the coveted Maudes Trophy in November 1939.

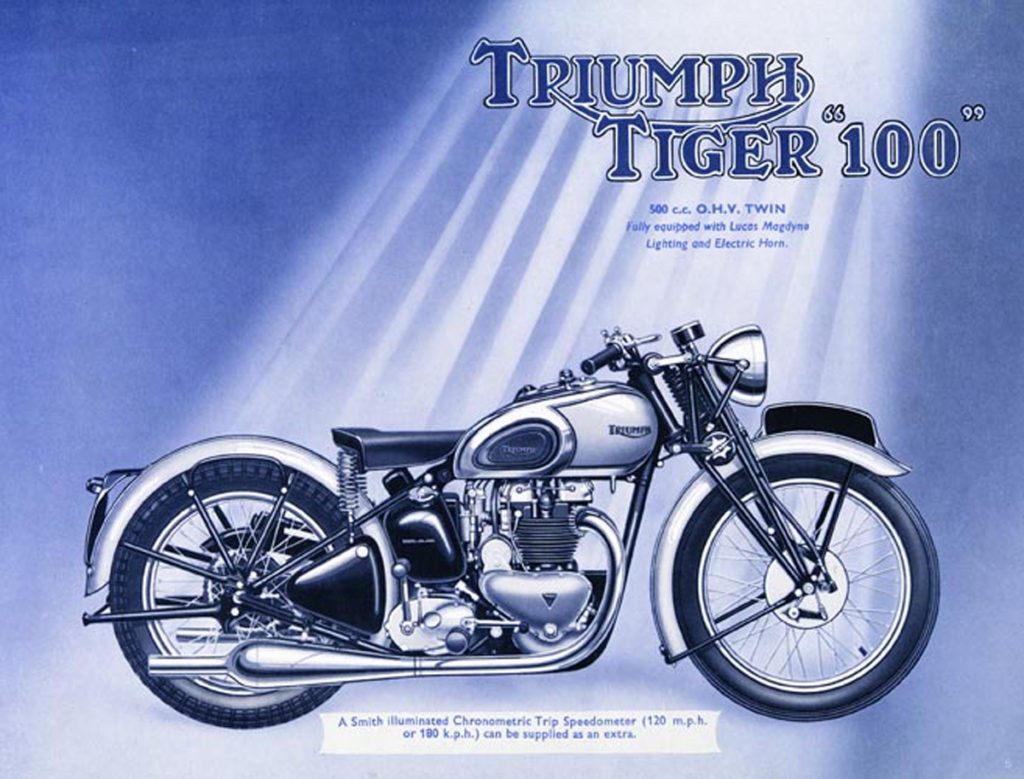

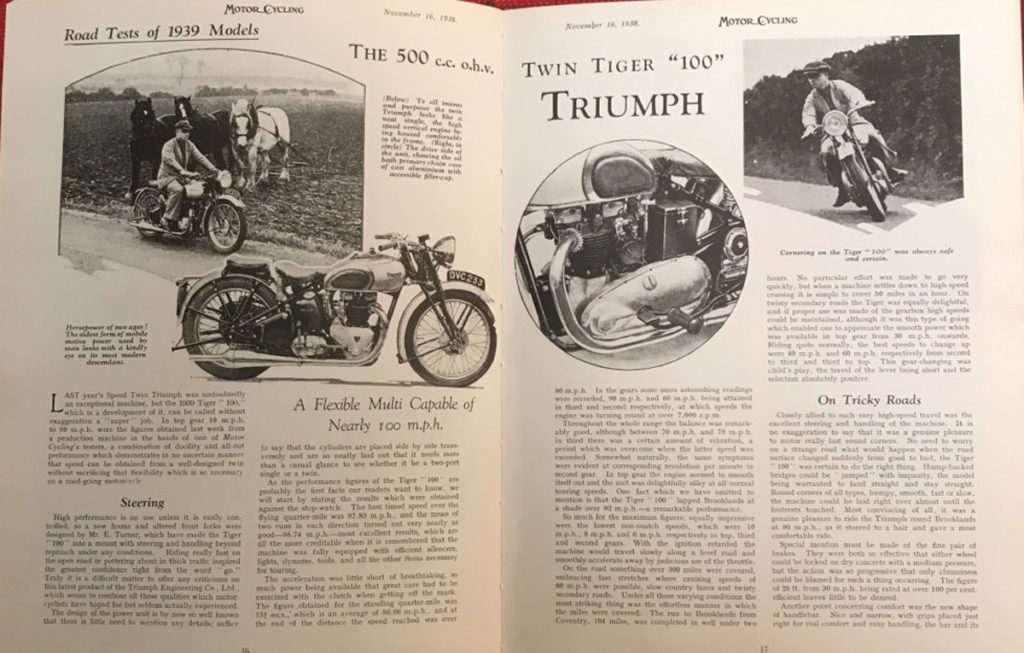

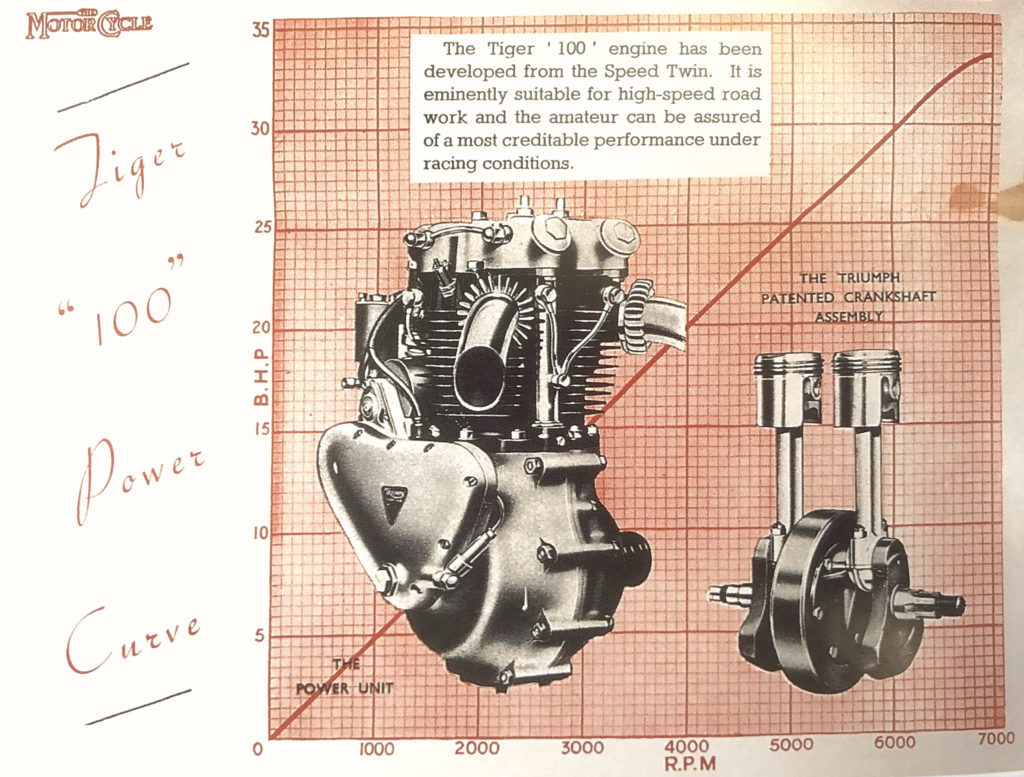

Triumph’s new Tiger 100 model was first tested by the British monthly Motor Cycling a year before (November 1938), and had reached 98 mph in full road trim, which was very fast; in those years, a family sedan might blow a gasket or worse if driven at 60 mph for any distance. The Tiger 100 cost £80 (plus £2 10s for the speedo), and would easily exceed 100 mph on open pipes. When Triumph introduced the so-called ‘cocktail shaker’ silencers for the 1939 season, riders could remove the quickly-detachable end caps and baffles, transforming the silencers into open megaphones. Every Tiger 100 built in Coventry (ie, before the factory was bombed during WW2, and rebuilt in Meriden, near Birmingham) came with a dynamometer test certificate, and differed from its Speed Twin brother only with 8:1 compression pistons, polished inlet tracts, and a 1/16” larger carb – enough for a claimed 8hp increase! By comparison, BSA’s 500cc M24 Gold Star single cost £82 exclusive of extras like pillion footrests and the speedometer and might hit 95 mph downhill with the wind behind it. The competition and racing versions were faster but cost more. A Vincent H.R.D. Comet cost £86 plus extras and was good for 90 mph with a jockey-sized rider aboard. To borrow the catchphrase of a motorcycle dealer I knew in London decades ago, who had started racing in the 1930s, the Tiger 100 was “a lot of bike for the money, son!”

The Picardy Tiger

But back to our Picardy Tiger 100, the King of Route 29. The story is third-hand, the main players no longer around, but it’s a good tale and worth telling, and probably true (or as true as such stories can be). My friend Laurent Mimart, or ‘Mimo’ to those who know him as France’s go-to man for pre-unit Triumphs, mentioned a 1939 Tiger 100 he’d heard of in Saint-Quentin, on the Somme river in Picardy. Yeah, we’ve all heard those stories, but we had nothing else going that day so we drove from Paris. The house was a 1950s time warp, and was full of Triumph motorcycles and spares dating from the 1920s to the 1950s. It took us a couple of hours to dig a 1926 sidevalve and its parts out of the earthen floor of the dungeon-like cellar with our bare hands. There was a rare and genuine 1953 US market 6T Blackbird parked in the hallway, its cylinder head in a crate in a bedroom serving as a workshop. The Tiger 100 sat behind the Blackbird, its striking but non-original green-and-black finish typical of an older French enthusiast’s fondness for personalising his motorbikes. Mimo and I didn’t care about the green paint, being riders rather than collectors; what grabbed our attention was the engine number prefix: 40-T100.

Let’s call the Triumph’s owner ‘Gaston Blanchard’. He had died and his brother needed to clear the house out, but he didn’t want to sell Gaston’s motorbikes to any Tom, Dick or Harry. They had to go to people of whom his brother would have approved. As we sat drinking coffee in the dusty old house, Gaston’s brother told us the story of the Tigre Cent as he recalled it. In 1966, or maybe it was 1965, the nineteen year-old Blanchard, a keen scrambles fan like many Frenchmen at the time, was looking for an old motorbike to use as a field hack. Someone put him in touch with a Monsieur Morin, a retired railway signalman who lived near Amiens, some eighty kilometres to the west of Saint-Quentin along the Route Nationale 29, a post-Napoleonic highway that runs almost as straight as a Roman road between the two towns.

Blanchard rode there with his brother. Morin did indeed have an old motorbike that he hadn’t used in more than a dozen years since the lights had stopped working because the dynamo was foutu (f*cked). It was a fast machine, though, a Tigre Cent that he had owned “since the war”. It was the fastest motorcycle on the RN29 for a time, except for a very loud motorbike that had overtaken him one night at high speed and pulled away into the gloom. Knowing that a Tiger 100 in good tune was capable of just short of the magic ton in road trim, Mimo and I wondered aloud if the faster rider might have been on one of the first postwar Vincent H.R.D. Rapides imported to France just after WW2. Blanchard’s brother disagreed, saying that Morin had spoken of having to hide the Tiger 100 before he could seek out the challenger to prevent the French armed forces from requisitioning it.

So this Tiger 100 had been in France since before the war? No, said the brother. It had been imported from England during the war, but before the German invasion. It was a 1939 machine, he said, laying a 1980s document on the table, which gave the date of first registration as 1939. According to the (few remaining) factory records that survived the German air raid on Coventry during the night of November 14th 1940, when the Triumph works were destroyed, Triumph produced a total of 8,818 motorcycles from January to November 1940, of which just 274 were Tiger 100s. The engine and frame numbers of Morin’s T100 suggest it rolled off the Priory Street production line in October 1939. So the French bureaucrat who issued a new registration document in the 1980s was not mistaken: the T100 was indeed made in 1939 but for the 1940 season.

Tigers in Wartime

After Triumph relocated to Meriden, the firm was able to complete a few orders using parts salvaged from the ruins of the Coventry works. The Hollywood actor Rod Taylor is said to have received his new Speed Twin in 1942, delivered in a crate marked as tractor engine spares. Maybe this was the bike Taylor rode up to Hollister in 1947 with other Hollywood area bikers, but that is another story. Some students of the subject believe the last ‘Coventry Tiger 100’ made was the racer ordered by Rody Rodenberg on March 30th 1940 and dispatched to the US on May 18th that year. Rodenberg’s specifications included the optional bronze cylinder head and an Amal TT carburettor. Sold at auction by Bonhams in 2010, Rodenberg’s T100 comprises frame number TF 4030 and engine number T100-31131, Triumph having dropped the year prefix by then, according to some sources.

The topic of late prewar and early wartime Triumph frame and engine numbers is worth a digression if only to save people from buying bitzas or, now that prices are rising, fakes. From 1937 on, all new Tiger engines were numbered in sequence, regardless of the model type. The 1938 Speed Twin engine, though not a Tiger, was included in this sequence, as was the Tiger 100 when it arrived for 1939. The 5T engine was fitted to the Tiger 90 chassis, which was given its Amaranth Red and chrome finish to distinguish it from the blue-lined silver-grey/chrome colour scheme of the Tigers. The engine numbers were prefixed by the year and model codes. The 500cc and 600cc engines were fitted to Triumph’s heavyweight chassis whose serial numbers were prefixed by the code TH for ‘Triumph Heavyweight’. The smaller models had lighter frames marked TL for ‘Triumph Lightweight’. However, the TH frame was barely able to absorb the power of the new twin engine and when racers and dragsters tuned their Speed Twins, frames and lugs would crack.

The Speed Twin engine produced 26bhp, or more with hotter pistons and cams. However, the six-stud barrel-to-crankcase joint was prone not just to oil leakage at sustained high revs, but sudden, violent separation as studs were ripped from the alloy. Triumph introduced a new crankcase and cylinder block for the T100 with an eight-stud joint. The cylinder head was also new, with a larger one-inch inlet manifold and polished ports. It was made by the Birmingham firm of Birco, which some say explains the B suffix to the part number: E1454B. Birco also produced the optional bronze head (as fitted to the Rodenberg racer) that cost an extra £7 4s or $36 at contemporary exchange rates. The prewar bronze heads were also numbered E1454B but Birco produced a batch of bronze T100 heads for Triumph just after the war, in response to orders from the United States. These postwar heads were numbered E2258.

Some tuners fitted the T100 head to Speed Twin engines as the head stud configuration remained unrevised. I have a low-mileage 1939 Speed Twin motor given to me years ago by the son of a London Ton-Up Boy who had used for a season in his Norton-Triumph Special as a temporary replacement for his blown-up all-alloy T100C engine. The Ton-Up Boy had fitted it with a new T100 iron head, and I can confirm that the Triumph sales blurb about ‘polished ports’ was no lie. The Tiger 100 came with 8:1 forged alloy ‘slipper’ pistons. Other than that, the internals were Speed Twin, including the camshafts. In other words, the standard engine produced 34bhp, 8bhp over the Speed Twin. Tuned carefully, it was capable of far more, as Triumph’s Chief Development Engineer Freddie Clarke proved when he set a lap record of 118 mph at Brooklands in 1939.

As stocks of the six-stud 5T crankcases were used up during the 1938 season, 5T motors were built using the new eight-stud crankcase and cylinder block but the existing 5T head. Towards the end of the 1939 production run, a few dozen 5T motors were installed in T100-spec TF frames. From then on, all Triumph heavyweights had TF frames. A total of 4,413 TF frames are logged in surviving Triumph records to 1942, by which time Triumph was in Meriden and concentrating on military motorcycles and other war-essential products. In other words, all genuine Coventry Tiger 100s should have TF frames but not all of the higher-numbered TF frames began life as Tiger 100s. As we know, just 274 of the 8,818 motorcycles made in Coventry from January to November 1940 were Tiger 100s. The first 1940 Tiger 100s would have been assembled from late-August 1939 onwards.

One of these was the Tigre Cent ordered by Monsieur Morin, Roi de la RN29 or King of Route 29 for a brief time early in the winter of 1939, before he had to hide his T100 from the French military and then, of course, the Germans. As a railway signalman, Morin was in a reserved occupation and therefore exempt from the military mobilisation of all Frenchmen of military age. This explains why he was around to collect his new Triumph from the firm’s northern French concessionaire, the Grand Garage Paul Passet in Amiens. Blanchard’s brother mentioned Passet’s as the place where his brother went to order spares for the T100. Founded by Paul Passet before WW1, the dealership had a second branch in Abbeville by the late 1930s, and sold other imported marques like BSA. Paul Passet’s son Georges was a well-respected Clubman racer in the 1930s. In 1970, when the Bol d’Or was held at the Montlhéry circuit south of Paris for the last time, Georges’ son Jean-Paul would race Triumph factory racer Percy Tait’s T150 triple, such was the close relationship between the Passet family and Triumph. The dealership closed down in 1980 and their old Amiens premises now houses the town’s Police Municipale.

Le Roi de Route 29

Many French speed freaks on two, three and four wheels tried their luck on the RN29 in the interwar years, after the abolition of speed limits on French highways in 1922. You could get up to full race speeds between the towns and villages along the 80-kilometre or 50-mile stretch between Amiens and Saint-Quentin, cutting across the Picardy landscape like a steel rule. Prudence aside, the law required that you slow down through built-up area, and the gendarmes would lie in wait, hoping to catch roadhogs and hooligans rash enough accelerate before the derestriction signs marking the end of the speed limit. As Morin told the Blanchard brothers in the mid-1960s, ‘les flics’ had nothing capable of catching his Tigre Cent on full song. Running from the cops was easier when they did not have radios to alert their comrades further up the road…but they still telephone ahead in the late 1930s. If hotshoe riders like Morin thought they’d been clocked, they would turn off the highway into the hinterlands, lying low for a while, before returning home through the back lanes. At night, it was even easier to vanish, by simply turning off their lights.

Morin, as an ‘essential worker,’ needed to travel between different railway signal boxes in the Amiens area, and had a fuel allowance for a motorcycle, but once the French authorities started requisitioning private vehicles (including more than 56,000 motorcycles, many of which would end up in German hands), Morin would have been expected to take the train to work, or to use a bicycle. No more gallivanting up and down the RN29. As mentioned, he must have hidden his precious Tiger 100, first form the French military, then the Germans. After the war, Morin retrieved his Tiger 100 from its hiding place and used it as daily transport, until the dynamo stopped working. After Gaston Blanchard bought the T100 from Morin, he used and abused it as a field scrambler for another few years until the magneto died. As anyone who has a prewar Triumph twin knows, the twin-lead version of the Lucas Magdyno is a rare item, so the T100 was going nowhere. Blanchard dumped it in the cellar of his mother’s house in Saint-Quentin.

Taking early retirement in the 1980s, the unmarried Gaston Blanchard moved in with his mother. He bought a 6T Blackbird and became quite keen on classic bikes, even subscribing to the British magazine Classic Bike and joining the Triumph Owners Motor Cycle Club, whose badge we found on his workbench. At some point Blanchard must have realised that his old T100 was in fact quite special, and worth restoring. His paint job was competent but gives the Tiger the look of a BSA. His homemade wiring harness was rustic and an eyesore with only thick red wires, but it works well. However, Gaston Blanchard’s engine-building and fitting skills were beyond reproach. He renovated the engine and transmission with genuine, new old-stock parts. The rare MN2L Magdyno is a Lucas-reconditioned unit dated 1954, with an expensive-looking bronze plate repair to the drive end bearing housing. It must have cost a lot, even in the 1980s. Judging by the faint traces of soot on the plugs and in the ends of the cocktail shaker silencers, which appear to be genuine NOS pieces (as nobody was making replicas back then), Blanchard probably fired the Tiger 100 up a few times to check the timing and lighting. We can be sure that he did not ride it as the bottom fork yoke was fitted back-to-front, interfering with the chassis geometry. It would have been dangerous. In any case, he had his 650cc Triumph, which locals remember seeing him riding from time to time.

We took the Triumph back to Paris, where Mimo and I sorted out the fork, and checked the engine and transmission. Jake Robbins Vintage Engineering supplied the right fork spring – Blanchard had fitted a spring from the lightweight chassis. The fork is not the 1940 type with the double counter-springs but that is just a detail, like the paintjob. The headlamp is wrong but who’s asking? It throws a beam up the road and finding an 8-inch original or a decent copy is not a priority. The priority is to run-in the motor carefully and take the Tigre Cent back to the Route Nationale 29, which still exists but was renamed the D1029, with heavy traffic routed on the new A29 motorway, built a few kilometres to the south. Mechanically, the motor is almost noiseless, with minimal noise from the transmission and gearbox. The cocktail shaker silencers emit a powerful burble that rises to a menacing snarl when the throttle is blipped. The twistgrip is a very rare, original example of the ratchet type available as an option to riders wanting a form of cruise control. It is useful as enables you to make hand signals, although most car drivers these days are unfamiliar with hand signals, apart from the single or twin-finger variety one makes after being cut off by them. I have never liked the rubber-mounted handlebars fitted to late 1930s Triumphs but tightened up good and hard, the bars don’t move and handling is very light and precise. Speed cameras and traffic cops with penalty quotas to fill each month will make it hard to beat Monsieur Morin’s times between Amiens and Saint-Quentin in November 1939, but we will salute his ghost as we give the old Tigre Cent a handful of throttle along the RN29. Perhaps the ghosts of World War One, who haunt the many battlefields along the route, will remember Monsieur Morin’s Triumph.

How can they not, when she sounds like this?

Related Posts

July 25, 2017

The Vintagent Trailers: Morbidelli – a Story of Men and Fast Motorcycles

Discover the story of the Morbidelli…

At 15 years or age in 1960 l bought a sprung hub Tiger 100. I paid 20 UK pounds for it. The engine was amazing. Sadly l destroyed it on the North Circular Rd, Hit a stationary car. No lights and that part of the road was unlight to. At our speed we had no chance avoiding the car. Tiger 100 wow l still love that amazing engine but too old to ride now.

Triumph Engineering Company, Ltd., Meriden Works, Allesley, Coventry.

This was a Coventry firm, with the exception of a short time spent in Warwick, while the new factory was being built, from the beginning to the end, 1983.

Hello Lino. Thank you for your comment. I’ve heard people from Coventry and Birmingham claim Meriden as their own. It is also considered to be part of Solihull. In the early 1940s, Meriden was a country village roughly halfway between Coventry and Birmingham. The Priory Street works were in Coventry itself, around 150m from the city’s cathedral. The firm did indeed relocate to Warwick for a short time, setting up in the Benford cement mixer factory, whilst Triumph argued with the Meriden rural district council because the village was not in an approved industrial zone. In 1941, while the new factory in Meriden was being completed, the firm also worked from the ruins of the Priory Street works. In May 1942, all production and management moved to the Meriden premises. Many Coventry employees remained with Triumph. I did not go into this aspect of Triumph history in detail because I was focusing more on the Tiger 100 we had found, and which another reader seems sure he saw back in 1970. Another Meriden factoid concerns its claim to be at the center of England.

Hello Prosper,

First of all, thank you for your reply and belatedly thank you for the excellent article.

As a proud Coventrian, I personally would never try to claim Meriden as part of Coventry. It has always been known locally to be in the borough of Solihull. There’s a sign saying just that AFTER you have gone past the old site of the factory on the long approach road to the village of Meriden, over a mile further on.

So not IN the village of Meriden and not IN Solihull.

Remember it was Coventry City Council that Triumph owed business rates to.

You make no reference to Triumphs official address I pasted at the top of the previous reply? This is the address from their own letterhead. Surely they know where they are?

On a lighter note, it’s very heartwarming to see the enthusiasm for the original Triumph, it’s a shame they just couldn’t have hung on a bit longer to catch this wave

Your points are well-taken, Lino! We could cause real trouble on Triumph enthusiasts forums by pointing all of this out. Imagine the flame wars! Coventry…Meriden…where they paid their rates. You will be glad to learn that we are building one of the other 1940 T100s up. Not an easy task given the rarity of forks and other parts like the rocker and oil pump feed union! But if it were easy, everyone would be at it, right? Mind you, I have taken the loafer’s way out with my 1939 5T/T100 engine. I’m putting it in a 1937 Norton 16H as a homage to Rex McCandless’ wartime Triton. Mind you, he used his Norton Inter, which had a cradle frame so I’m having to be inventive. However, it will mean another Coventry twin out there on the road, making babies smile and dogs bark. Best wishes, PK

Very strange …when a young motorcyclist, a friend took me in a place , near of St Quentin (beetween St Quentin and Péronne exactly ) and showed me a pre-war Twin Triumph , painted with a toilet brush. I think it was in winter 1971 or 72…

Since that time, I often think about it as it was quite abandoned in an farmer estate …

And in the eighties , I had the pleasure , as I lived in Amiens, to have coffee every saturday morning with Paul Passet, in the little bar sitting near of his premises … not long before the closing time . he had many stories to tell , and it was a pleasure.

And in his shop, as it had been opened long before WW1 , there were so much rarirties !!!

Regards,

Gigi , from Amiens

Gigi d’Amiens, Bonjour. Il semble fort probable que la twin avant-guerre dont vous vous souvenez fût celle que vous ayez vue il y a 46 ans près de Saint-Quentin. J’ai changé le nom de la famille. The painted finish was better when we found the T100 but, as Paul d’Orleans’ photographs taken in Paris show, not the correct colours.

It maybe the same …pre-war tigers are not so common in our countryside …Glad to know it didn’t finish as crap !

But this part of Picardie was quite rich and we found some british iron sleeping in barns …a friend found in this neighbourhood a G3LSC Matchless for peanuts few years ago …

There are many treasures sleeping in French farms, houses and barns, Gigi. I am sure that the Tiger 100 in the article was the same bike you saw 46 years ago. It had been used as a ‘scrambles’ bike by the owner and was badly beaten-up and painted with a brush. He restored it in the 1980s but you can still see all the scars from its hard life as a ‘field bike’ in the 1960s and early 1970s. However, he renovated the motor and the transmission to a very high standard using genuine old spares. But he was not so talented with the chassis. The fork yoke was installed back-to-front and the rear chain sprockets were 1.5cm out of alignment. It is a good thing he did not try to ride it and kept it parked in the house! He might have crashed and killed himself.

Bonjour

Avis aux amateurs je viens de trouver dans la cave du grand père le catalogue anglais triumph de 1938 et celui de 1939 avec 3 magazines motor cycle de 1942

Phil de Rouen