While stylistic exuberance can shroud its origins, racing has always been the #1 starting point of most custom bike styles – Class C racing begat the bob-job, dragsters led to the chopper, GP the café racer, and dirt racing the tracker and scrambler styles. Uwe Ehinger of Germany’s Ehinger Kraftrad isn’t a typical custom builder, and takes his inspiration from the far corners of racing; hillclimbing, ice racing, and now speedway. Speedway is the toughest genre of all to riff on, and few builders have successfully adopted what’s cool about these hyper-specific machines. Speedway bikes are absolutely minimal, and little about them has changed from their perfected golden era post-1930. A modern Rotax-powered racer could be set beside a 1930 Rudge-Whitworth or Harley-Davidson Peashooter, and one could justifiably wonder if any progress has been made in the sport? Then again, part of its enduring popularity is exactly this simplicity and tradition, which keeps the price of entry for spectators and riders very low.Ehinger Kraftrad’s remarkable ‘Speedster’; history through a hi-tech lens.

Traditional custom builders usually shun small bikes, and speedway racers are tiny, with ultralight rigid frames, single-cylinder engines, no gearbox, and flimsy forks. They’re delicate and fit only for a single purpose, so translating their visual cues to a roadworthy motorcycle, especially with a big-capacity V-twin, often looks like a fat man in a tutu. But two builds debuted this year have successfully captured the spirit of speedway; the single-cylinder ‘#7’ by Jeremy Cupp, and the Ehinger Kraftrad ‘Speedster’. Uwe Ehinger explains, “Jeremy and I both built speedway bikes – we discussed how two people can have the same idea at the same time. His machine is much more like a real speedway bike, and mine is more a mix from everything.” Still, it was Ehinger’s bike that took and award -‘Best Sidevalve’ – at Born Free 7.

You’re reading that correctly – the BF7 organizers stretched their category a bit to fit the Ehinger Kraftrad machine, which as you can see has an OHV engine. But the crankcases are sourced from a ’37 Harley-Davidson UL, with modified Knucklehead top ends grafted on. Uwe Ehinger considers the engine the heart of his creations, and chose the UL motor for its four cams hidden within that shapely timing chest. To anyone savvy with H-D history, the 4-cam motor is what the factory raced from the ‘Teens till today, and was first offered on a road bike in 1928, with the JDH. Four cams give better valve control, meaning higher revs and more HP, but in this case, the UL’s lifters don’t exactly line up with the pushrod positions for a Knucklehead. While H-D are reputed to never unnecessarily change anything, the truth is there’s little interchangeability of motor components between different models. For example, putting aluminum XR1000 cylinders and heads on an XL Sportster bottom end might seem a logical job, until you wear two footprints in front of a milling machine to make them fit. Same story with the Ehinger Knuck conversion – the tale is told by the pushrods, which sit at unnaturally wonky angles. Uwe doesn’t mind – that sort of thing is a calling card to the cognoscenti, who recognize the work involved to make it functional.

Part of that work was making new rocker arms to accommodate the odd pushrod angle, and therein lies a tale; one might picture a gifted mechanic sketching out the necessary design on a graph paper or even a CAD program, but Ehinger’s process goes far deeper than that. “Ehinger Kraftrad custom bikes are only 1% of my business; I do a lot of other work for the film industry and design consultancy. I’ve digitalized all Harley parts from 1903 to the present; that’s over 62,000 parts 3d modeled, and with this I can do 3d simulations of a running engine complete with stress analyses, just like the car industry. When I build an engine like the Speedster, it’s already been worked out in 3d, with all the angles, ideas, and materials required, before I even start. In the end I’m 90-95% certain the design will work well. When I first started digitizing in 2002, everyone thought I was crazy, but now with a 5-axis milling machine I can build a whole bike out of aluminum. I used to create animation for films, and also studied particle physics and engineering, and I’ve worked with Audi and Porsche, etc. The bikes were more a hobby until 2008 when I turned 50, and decided to move away from working with the big industries, and bring this technology to custom bikes.”

Ehinger Kraftrad customs might appear traditional, but how they’re designed and built is clearly not. Uwe Ehinger is digging through the past with a high tech toolkit, and while you might have only recently heard of him, he’s built choppers since 1977. He also spent ten years (’79 to ’89) unearthing vintage bikes from South America at a time they were more likely to be scrapped than restored, as documented in his book ‘Rusty Diamonds’. His love of vintage machinery is clear, and evidenced in the ‘Speedster’ even in his choice of rocker gear for the OHV heads; rather than use the aluminum covers of the Knucklehead, he’s kept the cast iron rocker supports exposed, showing off his aluminum rocker arms. The impression is no longer H-D, but J.A.P., looking more like a late ‘20s Brough Superior KTOR racing engine, which powered many a World Speed Record machine in the day.

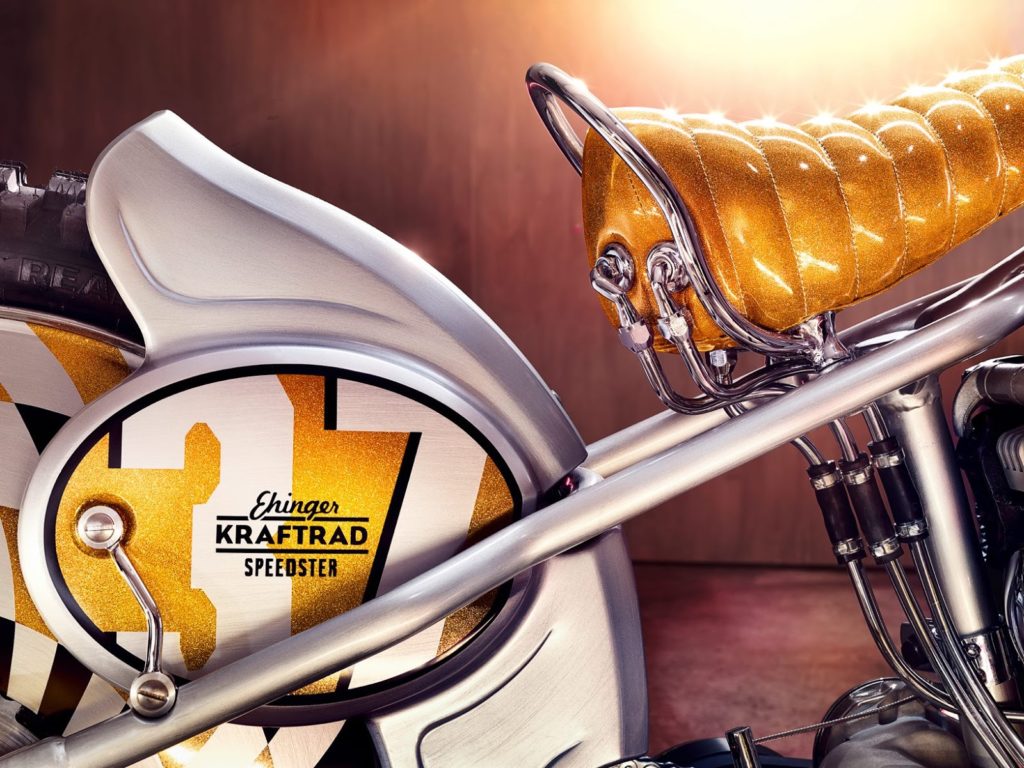

A shorter throw on the wayback machine explains the oil tank–cum-banana seat, a wholly unique creation harkening back to everyone’s Schwinn Stingray. Hidden under the metalflake vinyl padding, the oil tank is transformed into a psychedelic golden caterpillar. The oil filler sits at the seat nose, while the plumbing exits at the rear, and yes of course the seat is going to get warm, but the bike lives in Germany, not the Mojave desert, so it might remain a tolerable ride. That cater-padding extends atop the minimal fuel tank, which mimics a popular chop-job on Harley Peashooter tanks in the ‘30s, an example of which is famously housed in Jeff Decker’s basement. The headlamp is a chopper trope from the 1960s – a VW Beetle backup light.

Those unusual brakes are Beringers, originally developed for Cessna aircraft. Hardcore moto-historians like Uwe grok the connection between planes and bikes, especially as early motorcycles poached advances in aviation. We must thank Velocette’s Harold Willis for his the swingarm/shock absorber idea, inspired by the Oleomatic landing gear on his beloved Tiger Moth. OHV and OHC cylinder heads were adopted on aircraft a decade before they came into general use on bikes, although racers like George Dance grafted aero heads onto his sidevalve Sunbeams in the late ‘Teens. “The inboard brakes from Beringer are a nice idea – they’re originally from small airplanes. It’s hard to tell the story of motorcycling without the aircraft industry, but you need a lot of knowledge for an understanding of it. I felt it was over the top to try and discuss this at Born Free – nobody is really interested there.” Ah, but we are, Uwe!

Ehinger prefers to keep the steering geometry of his machines to the factory standard, and no longer builds raked choppers; “I use standard because it’s more reliable – its really about the bike functioning on the street, because it’s all about the road in the end, not the show. It’s nice to have a good-looking bike but it’s all bout the street. To have a non-riding bike is stupid.” He adds, “It’s not an original idea to put the OHV top end of the sidevalve lowers – Koslow did this in the ‘30s. My idea is to make the mix 100% H-D, but surpass what H-D did. For example I’ve used the ‘70s Sportster bottom with a Shovelhead top end for drag racing, it’s not a new idea but different in the way I did it. In bikes everything has been done before – today everyone is talking about 8-valve motors, and those ideas are a hundred years old.”

Ehinger’s ‘mix of everything’ method includes, as he puts it, ‘a bit of a California beach cruiser vibe’, although the mechanical details are too gnarly for a cruise. Wild handlebar risers attach to clip-ons, creating an aggro roadster stance atop the narrowed springer forks. The horn of the black Schebler carb is no bong song; it’s a racer’s trumpet, and the faired metal number plates integrated with the hyper-abbreviated rear fender (with a classic H-D kicktail) all suggesting competition. That dramatic rear-wheel disc cover is a speedway convention, being a convenient spot for team colors or sponsor logos on racers with no other sheet metal. The disc is the first thing one sees on the Speedster, and its arresting signature; the black/gold/white pattern was actually borrowed from a hypnotherapy book. Gaze deeply on the wheel…relax…you will like the Ehinger Kraftrad Speedster…and will open your eyes feeling alert and refreshed.

This article orginally appeared in Cycle World: subscribe here to the world’s largest-circulation motorcycle magazine!

Loved watching the heroine on the Indian jump into the river chasing the train. You can see me road racing the ’26 Indian and ’51 Velo MAC next year in AHRMA western races. Maybe a movie?2

JDH is a Two Cam, not 4. Right?