Memorable races match two top rivals of comparable skill and equal valour, driven by the need to succeed, riding machines at the leading edge of performance, backed by well-drilled and determined teams. The Isle of Man Tourist Trophy provides the perfect setting to test man and machine, with challenges of the timed interval start, the mountain climb and weather, and the ordinary roads. My “Greatest TT race”, the Senior TT of 1935, brought all this together to provide one of the epic races of all time. But the story of this race really began in 1933.[By David Royston]

Preparation

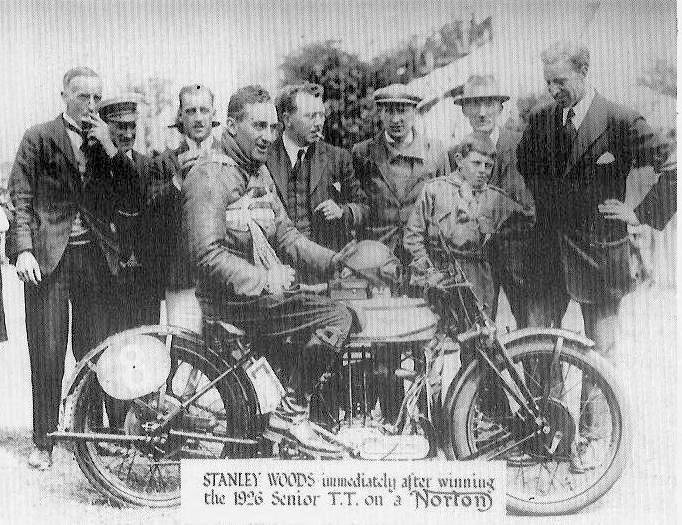

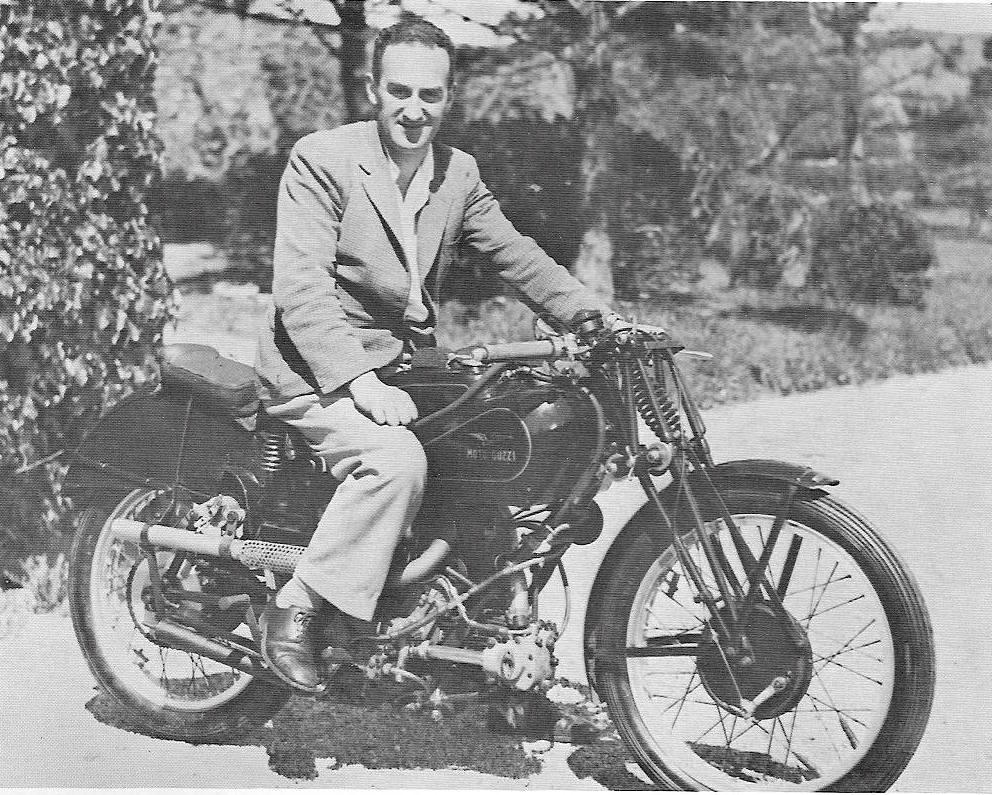

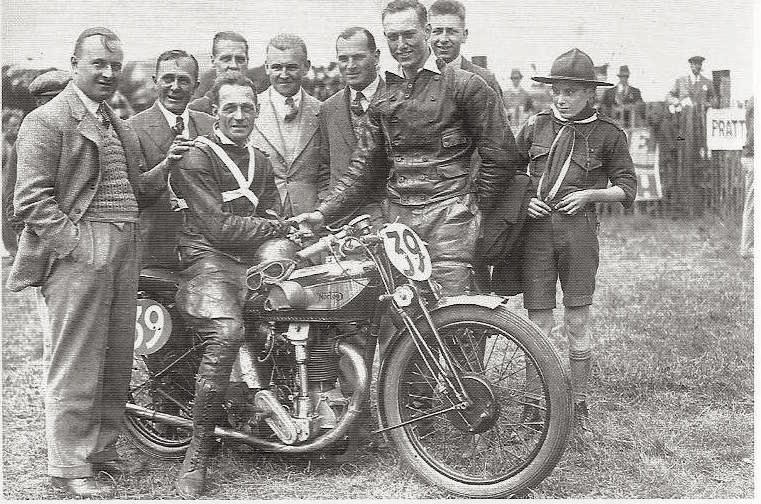

Stanley Woods, a Dubliner and rider of outstanding talent on any form of motorcycle, began his TT career in 1922 as a precocious 17-year old. Initially he combined riding with his work as a salesman for the sweet makers Mackintosh’s. In the following years Woods would provide boxes of toffees (from a business with his father) for the boy scouts that ran the leader board at the TT. He won his first (Junior) TT in 1923 on a Cotton; he moved to Norton in 1926 to win the Senior TT that year (at 21) and to begin a string wins for Norton including the Junior and Senior TTs in 1932 and 1933. By 1933 Norton had established such supremacy its winning was called “the Norton Habit” and the team began to allocate wins to particular riders in the team. This did not suit Woods who was the Norton team’s star. By the early 1930’s, motorcycling had become a professional sport and Woods, now at his peak, relied on wins and retainers to make his living: he decided to leave Norton. For the 1934 TT he was retained to ride the 500c twin Folke Mannerstedt designed light, powerful, but thirsty Husqvarna.

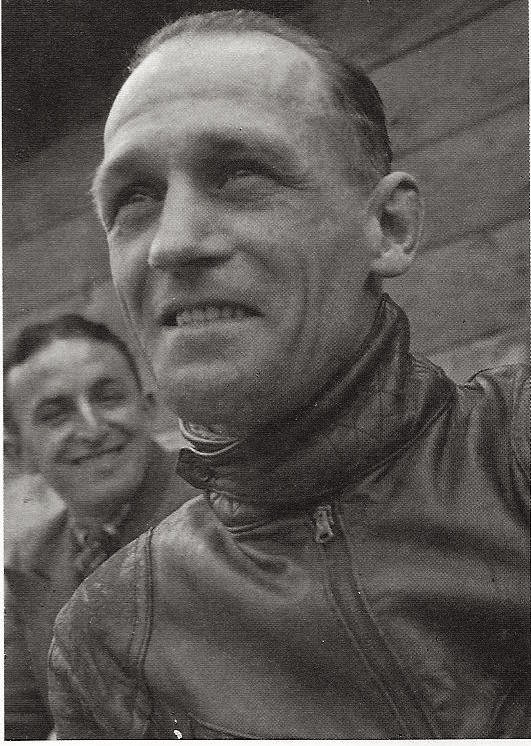

Jimmie Guthrie was from Hawick in Scotland, where he ran a successful motor business with his brother Archie. A survivor of the horrific 1915 Quintinshill troop train rail crash near Gretna, he served in Gallipoli and Palestine, then as a dispatch rider at the Somme and Arras. Guthrie had come into national motorcycle racing in his late 20’s, competing in his first TT in 1923 (the year of Woods’ first win). Four years later he returned as a regular competitor; he finally got a works ride with the Norton Team in 1931. Guthrie was well aware that he was older that other competitors and he had a vigorous training programme to keep fit. Guthrie took over as the lead rider for Norton at the end of 1933 and immediately showed he was on top of his form. He made his mark winning the 1934 Junior and Senior TTs. The latter after a strong challenge to the Norton team from Stanley Woods. That challenge failed on the last lap with a spill at Ramsay Hairpin followed by the Husqvarna running of fuel 8 miles from the finish: the feared threat from foreign machines, ‘the foreign menace’, was at the doorstep.

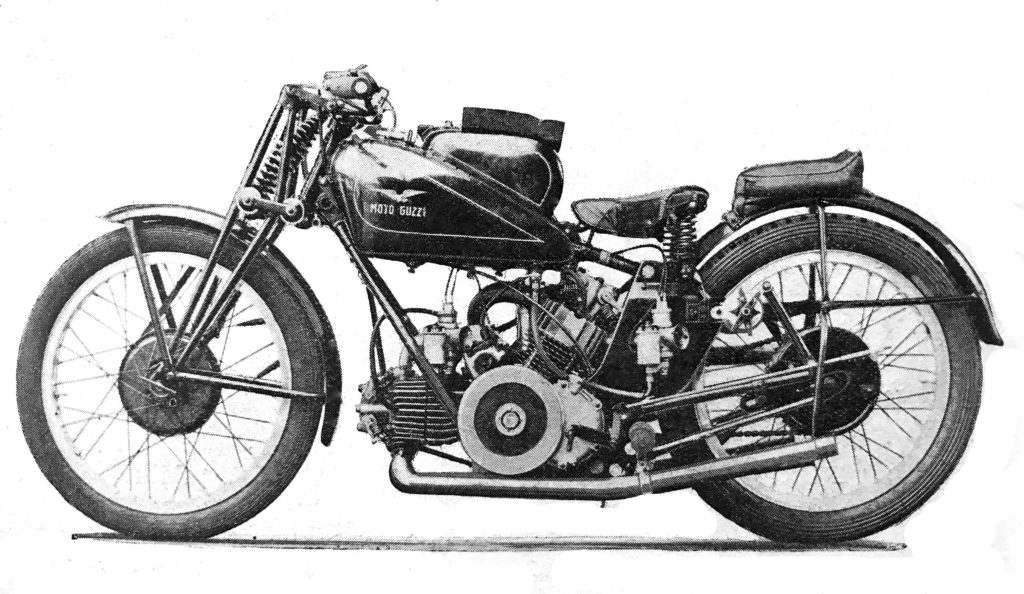

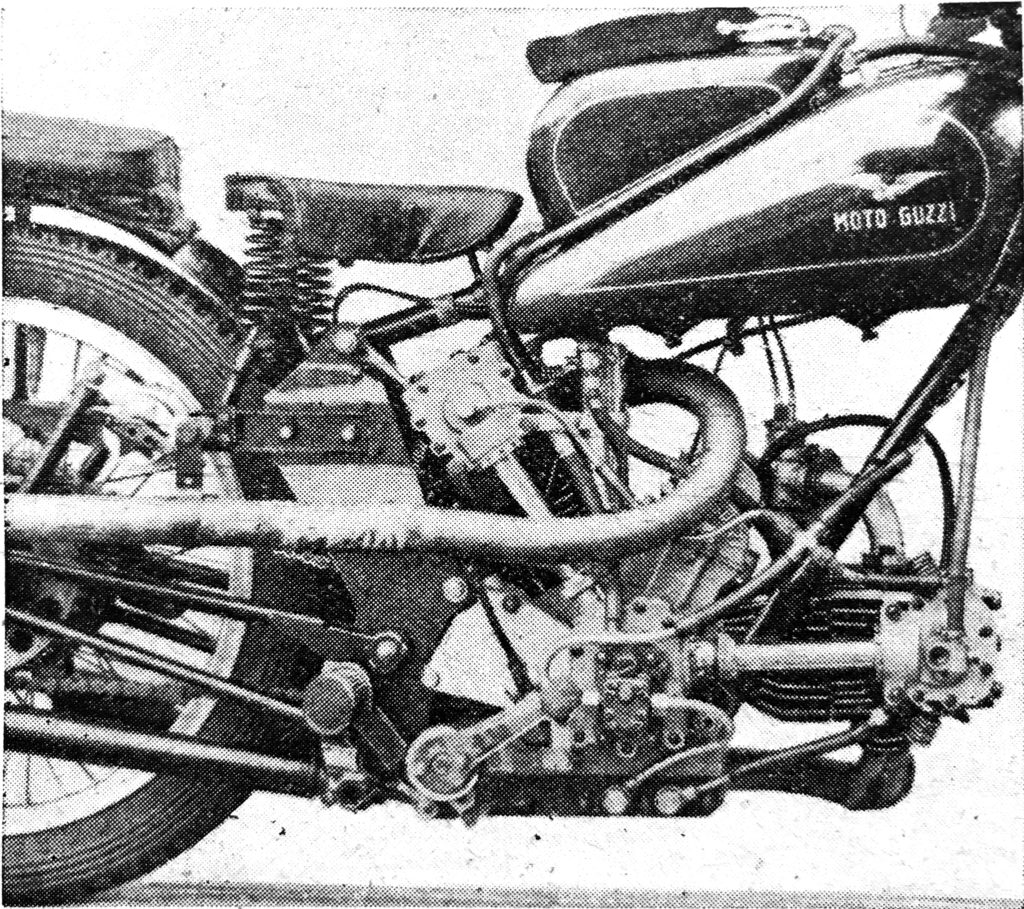

By 1935, the Norton team was a well-oiled TT-winning machine with ‘the Fox’ Joe Craig (and his TT signal stage system) in charge. Its bike was the best in the business. Walter Moore designed a powerful ohc-single engine in 1926/7 for Norton (Moore used the Chater Lea system for reference; Stanley Woods said impishly Moore took the worst aspects from it). Though the engine was an immediate winner it was unreliable and was progressively redesigned and improved significantly from 1929 by Arthur Carroll and Joe Craig, to more closely resemble the Velocette system of 1925; Moore had ‘copied the wrong one!’ The 500c engine probably was developing 35-38 bhp by 1935 (sadly the year Arthur Carroll died in a crash while riding his fast ‘tweaked’ side-valve Norton). The TT Norton had a good handling (for the period), though it still used a rigid frame with girder forks. The whole package was refined with an emphasis on lightness. Velocette was still in its wilderness years: it had pioneered the ohc single successfully at the TT in the late 1920’s but had lost its way at the top level on frame design and brakes.

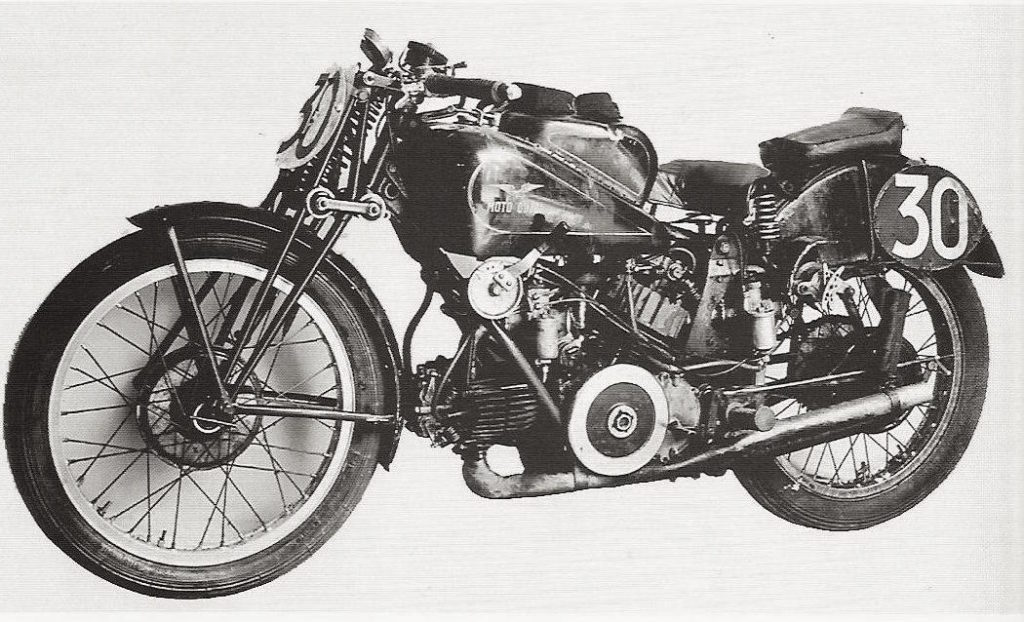

In practice for the Senior TT, Norton preparation was developed to new levels. But in the background there were reports of high speeds from the Moto Guzzi including on the last day of practice an unofficial lap record. Then Stanley Woods won the Lightweight TT on a 250cc horizontal single Moto Guzzi, a first for a foreign bike: the ‘foreign menace’ had arrived.

The Race

Fog covered the Isle of Man on Friday June 21st the day of the Senior TT and the race was postponed to 11 am the next day. As Saturday dawned fog still covered the Island and many were concerned that the race could be cancelled. The start was put back half an hour to 11:30. With tension building the clock crept towards the new deadline. Finally the fog lifted enough for the race to start; all involved looked to the event with great expectations.

The third lap was the one where teams were to take on fuel. Guthrie came into the pits after yet another lap record of 26 minutes and 28 seconds. The Norton team moved smoothly into well-practiced action and had him refuelled and out in 33 seconds by the reporter’s stopwatch. Almost 15 minutes later Woods came into the pits now 52 seconds behind and, to the surprise of onlookers, in a lightening stop was away in 31 seconds by the same watch. With such a short stop there was speculation as to whether the twin had enough fuel to make the next four laps at record pace? Especially given the Husqvarna experience the year before.

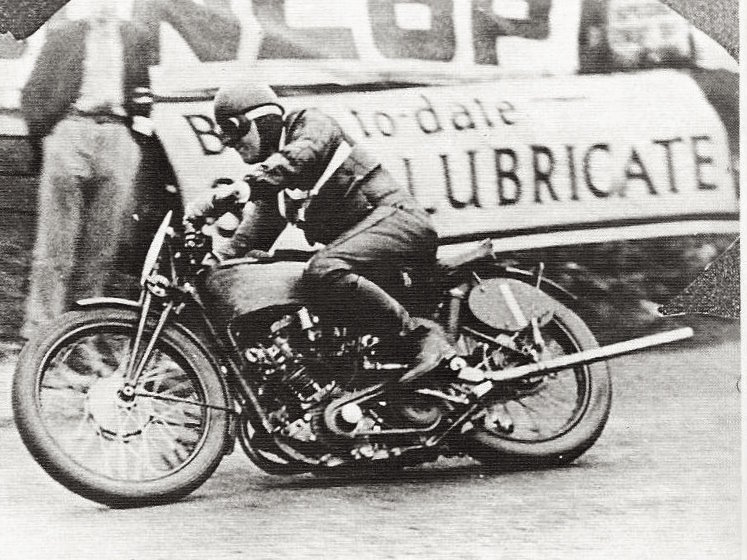

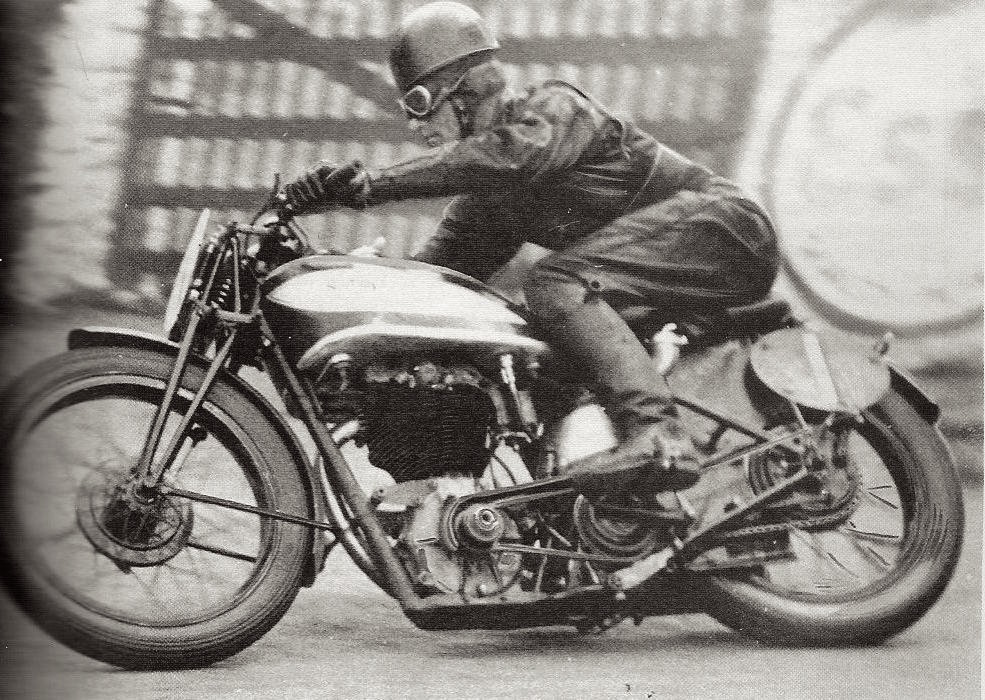

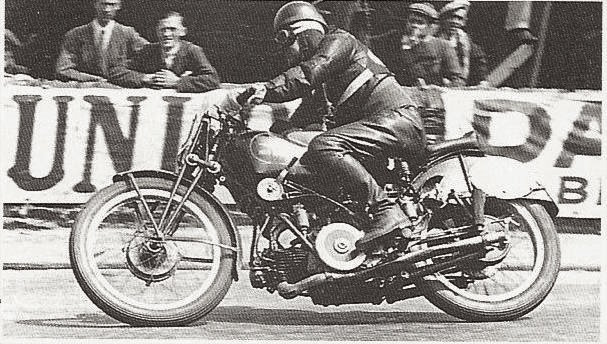

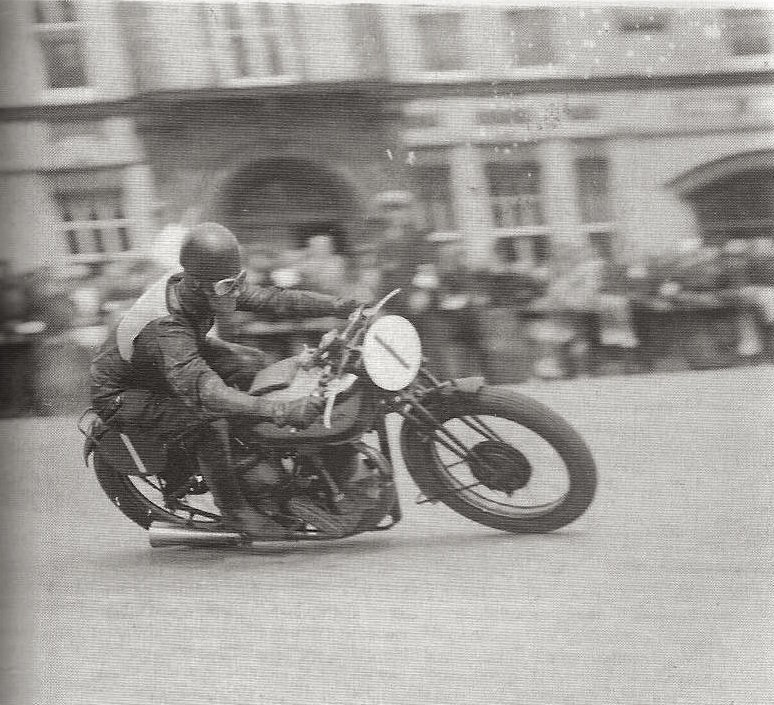

On the Fourth Lap, both Guthrie and Woods continued at near record pace. Motorcycling magazine shows pictures of both riders and their bikes coming down Bray Hill. The Norton has its front wheel in the air; the Moto Guzzi is firmly planted on the ground. It was said the sprung frame could be worth as much as 20 seconds a lap, would this tell? Woods closed the gap to 42 seconds.

On the fifth lap Woods reduced the lap record to 26 minutes and 26 seconds, closing the gap to 29 seconds. He had pulled back 13 seconds on just one lap; the challenge was on.

We now come to end of the critical sixth lap. Guthrie’s Norton went through without stopping. The Moto Guzzi team busied themselves setting up for a fuel-stop and the grandstand crowd expected Woods and the thirsty Guzzi to stop for fuel. Joe Craig may have thought Norton had the race won. It is said he had sent signals to his station at Glen Helen for Guthrie, almost ⅔ of a lap ahead, to ease his pace perhaps fearing the record laps could affect the bike and the rider.

Stanley Woods and the Guzzi could be heard approaching the Grandstand. To the surprise of everyone but the Guzzi team, he shot through, on the tank, flat-out, now 26 seconds behind: man and machine on a mission. Could the Moto Guzzi pit-stop ploy have made a difference? Norton immediately rang through to Ramsay to signal Guthrie to speed up. It was now all up to Woods. As Mario Colombo (from a Guzzi perspective) puts it: “L’ultimo giro, il settimo, si svolge in un’atmosfera di tormento e di sofferenza, gli occhi al cronometro, l’orecchio teso” (“The seventh and last lap unfolded in an atmosphere of suffering and torment, with all eyes on the stopwatches and all ears alert”). Reports were coming through that Woods was running fast all around the circuit: the Moto Guzzi ‘bicilindrica’ was rising to the occasion. At the base of the mountain he had the gap down to 12 seconds, down the mountain he had the bike wound up to 125mph. At Creg-Ny-Baa the gap was 6 seconds. Guthrie had come through on his seventh and final lap at near-record pace – he knew Woods well enough maybe not to trust the signals. Colombo writes: “Guthrie arrived at the finish and silence fell like a tangible thing: everyone had their eyes fixed on the beginning of the final straight”. Not all it seems, the officials and the radio commentary, based on the times from the sixth lap, thought Guthrie had won. He was toasted and congratulated by the Governor of the Isle of Man. Motorcycling magazine has a photograph of the Guthrie and the bike surrounding by supporters as a smiling ‘winner’. An official was leading Guthrie to the microphone when, after 14½ minutes of suspense, with its characteristic roar, the red Guzzi with Woods “buried in the tank” flashed across the line. “A thousand stopwatches clicked and feverish calculations were made”. That official was stopped with the news that Woods had won by 4 seconds. He’d done it. Woods had ridden an outstanding last record lap (26minutes and 10 seconds, 86.53 mph). His race time was 3 hours 7 minutes and 10 seconds, an average speed of 84.68mph. The crowd understood the significance of the moment, setting aside any thoughts of the ‘foreign menace’, the grandstand rose to cheer the winning team and rider, “…spectators thronged around Guzzi, Parodi, Woods and the mechanics in a display of sporting spirit those present never forgot”.

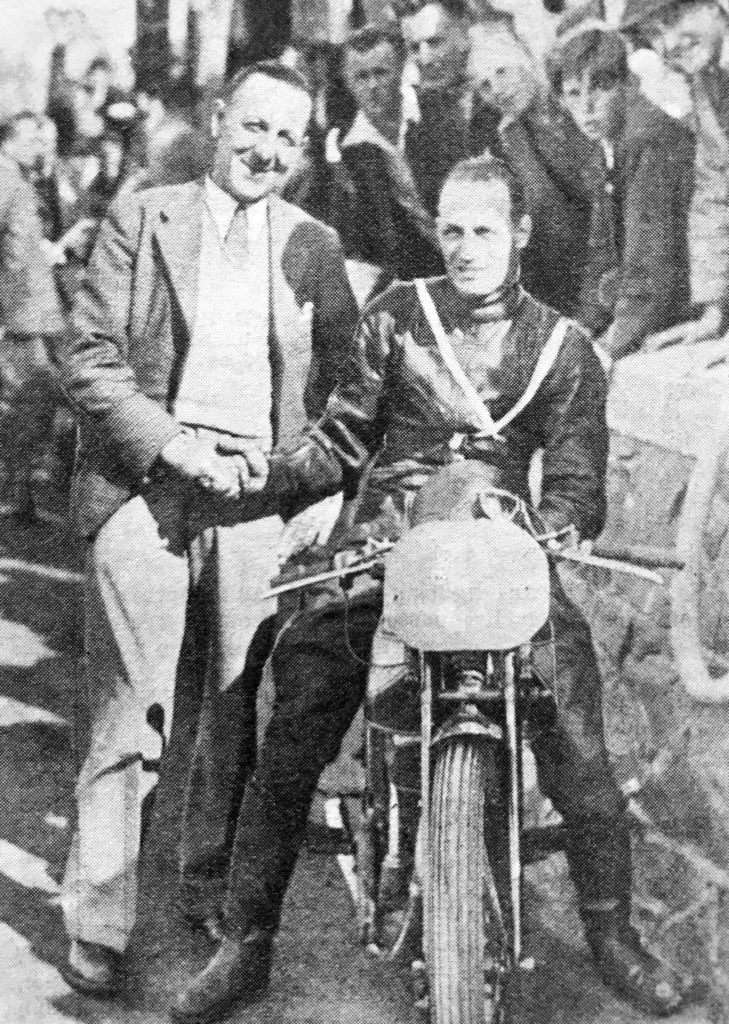

Guthrie looked dazed by the abrupt change of fortune but took it in good grace reflecting the depth of his character and reserved manner (off a bike!): he was amongst the first to congratulate Woods. After the race Jimmie Guthrie said; “I went as quick as I could but Stanley went quicker. I am sorry but I did the best I could.” They were friends as well as rivals. Stanley Woods said years later: “I turned on everything I had on the last lap. I over-revved and beat him by 4 seconds and put up the lap record by 3-4 mph. And that (beating Norton), I think, gave me more satisfaction and more joy, the fact that I had beaten Norton. Its what I had set out to do. It was very very satisfactory”. MotorCycling magazine carried a second photograph with Stanley Woods, and his trademark grin, as the true winner of my ‘Greatest TT’.

Was the difference in those pit stops? It is possible both riders covered the ground in the same time. What about the fuel in Wood’s tank? A reporter said there was an inch in the bottom almost enough for another lap; it seems that the Guzzi did have an extra-large tank for the TT, maybe it was very full on the first slow laps. MotorCycling magazine discussed whether the fake pit stop was sporting but accepted the tactic as legitimate (quaint considering team tactics these days). Perhaps for once the fox was just outfoxed?

What happened to these two great riders? Guthrie continued with Norton and turned the tables in the 1936 Senior TT (winning by 18 seconds over Woods now riding for Velocette). In 1937 Guthrie won the Junior but his bike broke down at ‘The Cutting’ in the Senior. He was killed later that year (at 40) while leading the German GP at the Sachsenring. Woods was slowed in that race (by broken fuel line) and saw a rider ahead too close to Guthrie. It was said the accident was a result of mechanical failure. Woods, interviewed in 1992, said he thought Guthrie had been forced off line and into the trees at the Noetzhold corner. Woods was the first on the scene and went with him to the hospital: “the surgeon came out and said that they’d revived him momentarily, but that he had died. You can imagine how I felt. We’d been friends, team-mates and rivals for ten years. I was shattered.” The ‘Guthrie Memorial’ stands where he had stopped in his last TT; the ‘Guthrie Stone’ marks the accident spot at the Sachsenring. Woods won the Junior TT for Velocette in 1938 and 1939; also with Velocette he was a close second to Norton in the Senior TTs of ’36,’37 and ’38 and just missed third by 6 seconds behind Freddie Frith (Norton) when the BMW supercharged bikes took first and second in 1939. Woods did not return to racing after 1945 but did test rides (including on the Guzzi V8 in ’56) and demonstration rides at the TTs into his 80’s. It took Mike Hailwood to beat his ten TT wins. Stanley Woods died in 1993 aged 90, still regarded by many as the greatest rider of all.

Hi I have alot of pictres from this race