The attempt was set in motion by Velocette managing director Bertie Goodman. Veloce Ltd were a small, family-owned company with a peerless reputation for quality machines, and an excellent racing pedigree. Unlike the Board of nearly every other motorcycle manufacturer, the helmsmen (and women) of Veloce were daily riders of their own machinery, and enthusiastic supporters of racing, to the extent of participating in record runs and even the occasional international-level road race. For example, during his stint as Sales Director, Bertie placed 3rd in the 1947 Ulster GP, and his son Peter had significant success in racing as well.

As Managing Director from the 1950s onwards, after the death of his father Percy Goodman, ‘Mister Bertram’ (as factory employees called him) took special pleasure in speed-testing the company products at the MIRA test-track, which he insisted helped keep his weight down! Such testing proved excellent for revealing faults, and Velocette production models were renowned for their mechanical reliability and excellent handling.

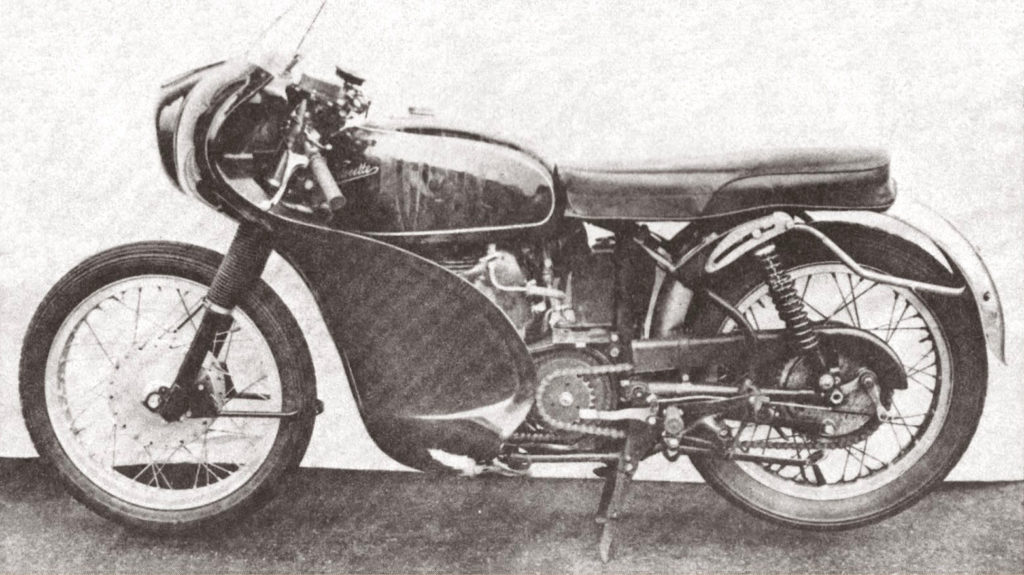

Their nearly standard ‘Venom’ 500cc model had been very carefully assembled, but was not highly tuned. Goodman insisted using time-proven production parts meant less likelihood of component failure, so the record-breaker Venom differed from standard only in the addition of a GP racing carburetor, megaphone exhaust, and production prototype fairing, made by Doug Mitchenall, a friend of the Goodman family, and manufacturer of Avon Fairings (and the beautiful bodywork on Rickman motocrossers). Much was removed from the Venom though! The front mudguard, battery, lights, speedometer, number plate, headlamp cowl, primary chain cases, etc, were all removed, probably 50lbs of extraneous metal.

Building the record-breaker Venom took 5 months, as the Veloce race shop had closed 8 years prior, after taking 2 World Championships and countless Isle of Man and GP victories, in a bid for the tiny, family-run company to focus on their production roadsters. When the bike was completed, Bertie Goodman tested it at MIRA for 14 hours at absolutely full throttle, averaging nearly 110mph. The engine was never internally inspected or disassembled during or after testing; that means it ran 1400 miles at full bore, before the record attempt had even begun.

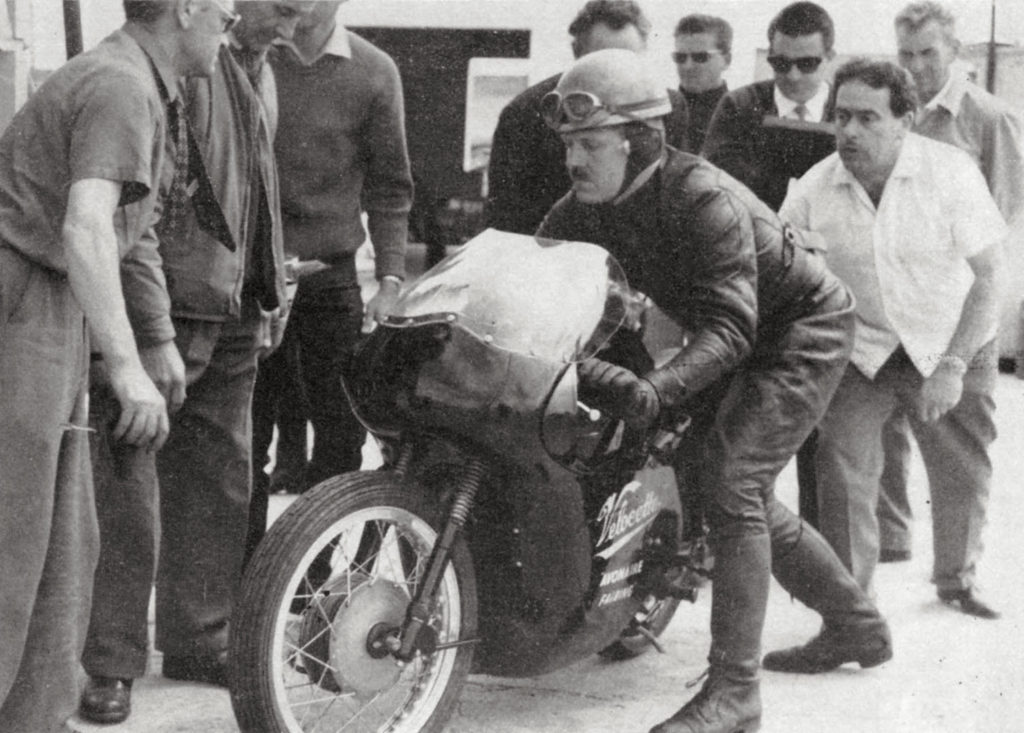

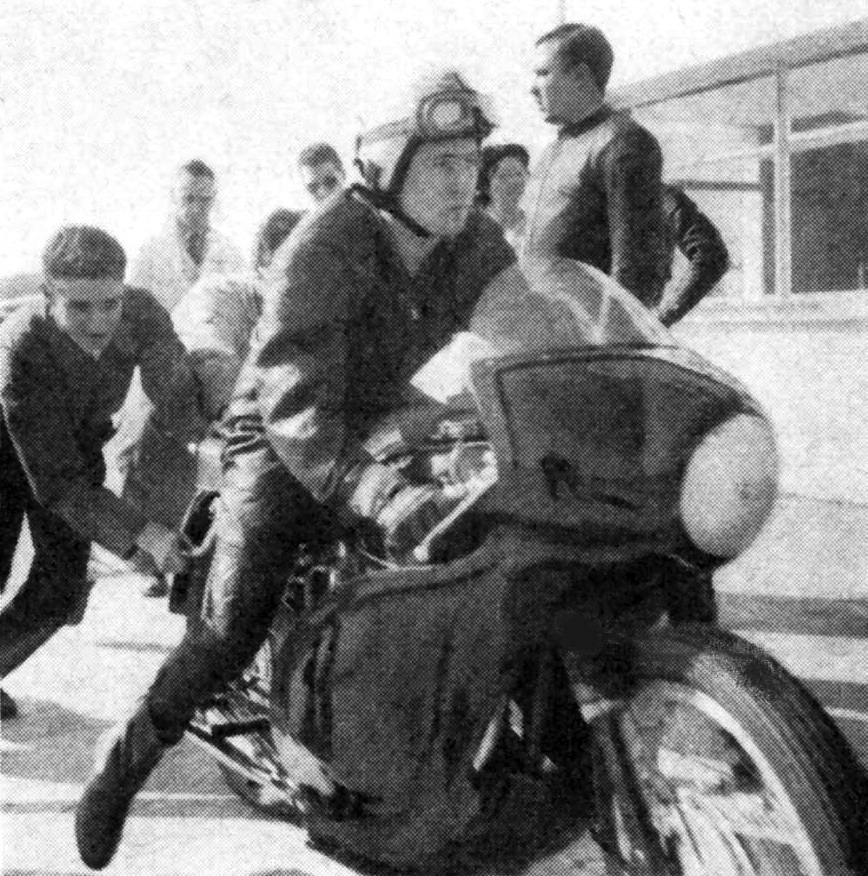

Management of the record attempt, including sponsorship deals and track arrangements, was the job of Georges Monneret. As the Montlhéry circuit had no lights, the 12 hours of night riding were illuminated by 55 Marchal car headlamps connected to batteries! Rider testing – to determine team members – was carried out the night before the record attempt; if you didn’t have the ‘bottle’ to keep the throttle right at the stop, you were out! The team thus consisted of Bertie Goodman, Bruce Main-Smith, Georges and Pierre Monneret, Pierre Cherrier, Alain Dagan, André Jacquier-Bret, and Robert Leconte. While Bertie Goodman was a relative ‘oldster’ at 42, Georges Monneret was 55 at the time… and of course, these two old dogs were among the most consistent and fastest of the attempt.

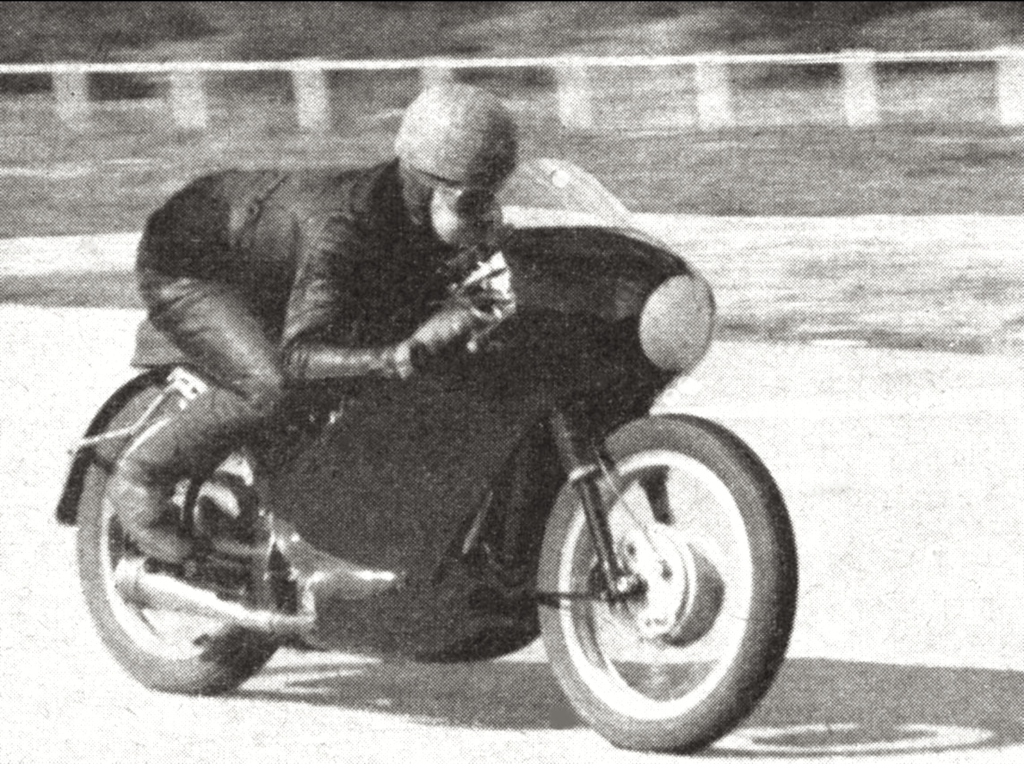

Night riding at 107mph through stroboscopic bands of light and dark proved psychologically demanding in ways the riders could not have anticipated; hallucinations, hypnosis, and phantom ‘fog’ beset every rider, and those with steely temperaments (Goodman, Dagan, and the Monnerets) shouldered the heaviest riding burdens. The bumps were awful, but the Velo steered as they all do, “taut, waggle-free, 100% safe” said BruceMain-Smith, in his epic writeup of the event. He wrote “I am genuinely frightened…punishment from the bumps is awful…my nose and mouth run, onto the chin pad to which I press my head to keep it behind the screen…it seems an eternity…the noise from the megaphone chases me round the track like a wild beast…after 60 laps I know it would sabotage the attempt if I continued. I come in…” He finds motivation to continue, thinking first of his Country, then his readers, and finally – that he was being paid!

The rough hours of the day passed into evening, and with them the 12-hour record at 104.6mph. Worth celebrating, but the grim reality of constant pounding and a further 12 hours’ riding meant no champagne. The nightmare hours hammered onward, punctuated only by fuel stops and rider changes, at times after only 15 minutes, as younger riders complained of blurred vision and fatigue. The older riders (Goodman, Monneret) dutifully fulfilled every one-hour stint, while young Dagan, the fastest of them all, was first to leap onto the saddle and revive the average speed when others flagged or surrendered. By morning’s first light, he made the final push, bringing the Velo over the timing line for the last time. All were exhausted, cold, and ready for sleep! Yet, for 2400 miles and a road average of 107mph, the Velo never skipped a beat, and gave a remarkable 37mpg, ridden flat out. When the engine was finally opened for FIM inspection, after 3800 miles of 100+mph riding, it was found to be in perfect condition.

A slice of life in the fast lane!! Great read. Thanks again.

Wonderful, Thank you Paul! Perfect timing for the spring fever. It inspires to get the Velos out sooner this season!

Superb post Paul – an inspirational account of courage and determination.

Superb read! Really Great post, Thanks for sharing

Bertie Goodman looks like a regular bloke, doesn’t he?

Such a wonderful achievement this 24 hour record from a factory of self-made engineers and craftsman. We may never see the like again. Thank you, Paul.

Actually, the bulk of current record-breaking is privately financed and engineered. Folks like Alp Sungurtekin build their dreams and break records with old engines, proving heroism isn’t dead!

Hey Paul, there seems to be a twist in the story….an extract from ‘Velocette motorcycles MSS to Thruxton’ Rod Burris – ‘ Suddenly one of the French riders dropped the machine and about 30 precious minutes were lost while race mechanic Jack Passant sorted out the gear selection problem that resulted. Eventually the team succeeded in achieving the 24 hour record by averaging 100.05 mph. This machine was seriously damaged in a fire at the National Motor Museum and has been restored by Ivan Rhodes.’ So they just made it by the skin of their teeth.

I had the pleasure of working with Doug Mitchenall in the 1989. He knew everything there was about GRP and working for him meant that he would scrutinise everything you did, there was no place to hide! Doug showed me an insight into engineering and manufacture that I still use today, perfection at every level. He even gave me a nickname, ‘CB’. I still use it today, ‘Cleverbee’

I was aware of this record from years ago. The source of the informations was lost to me in the mists of time, although it may have been through Geoff Dodkin, not sure.

So it is an absolute delight to come across this great article with accompanying photos, Bravo.

My Venom has just celebrated its 50 anniversary of my ownership !