John McInnis is a designer working under Alta co-founder Jeff Sand, the Chief Design Officer and original architect of the Alta Redshift motor. McInnis came to Alta from Lightning Motorcycles, where he was responsible for Class A surface modeling on its LS-218 electric superbike that broke records at Bonneville (the ‘218’ was its top speed on the salt) and kicked the ass of every dinosaur-powered factory racer on Pike’s Peak in 2013.

At Alta, McInnis’ role bounces between surface/solid modeling, concept sketching, and a little bit of graphic design. All of which are his favorite aspects of the design process. “I definitely feel fortunate to have found myself here; it’s an absolute dream job,” he told me from his office in Alta’s Brisbane, California headquarters – eight miles south of downtown San Francisco. “Alta is definitely doing some of the raddest things in motorcycling and it’s great being a part of it.”

And it doesn’t get any radder than a silent dragster called the Crapshoot.

Q: John, how and when did the Crapshoot project begin?

We knew we wanted to bring another bike to The One Moto show in Portland, the question was obviously “what?” Jon Bekefy, our marketing director at the time, had challenged me to come up with something unexpected; something you wouldn’t see any other electric OEMs do. We agreed it wasn’t going to be a café or a scrambler, because that felt just a little too obvious. Some other ideas we threw around were an `80s GP-inspired muscle bike or a speedway bike before we landed on one of the most niche segments: vintage drag bike!

After looking through the history books, some of the builds that stood out to me were by Boris Murray with his twin-engine, fully-faired Triumph and Leo Payne, creator of the awesome “Turnip Eater” Ironhead Sportster. These guys built these fantastic machines out of garages in the `60s, and I wanted this build to reflect that “handmade-ness”. My mission was to prove that a regular guy with regular tools and basic fabrication skills can take a Redshift and turn it into something pretty wild, without needing to be an electrical engineer. So in that spirit, all of the electronics and the core of a bone-stock Redshift remained unchanged.

Q: How many different versions were explored before this one was built?

I had only done a handful of pen sketches and one digital sketch before people were pretty excited about it and the rough silhouette was solidified. I had planned on it being a hardtail from the beginning, and getting it as low as possible was a priority. Once I created the hardtail section in CAD, that part stayed the same. The bodywork changed based off of what I could get in the limited time and what would fit best on a 250cc equivalent dirtbike (not much..) but the people at AirTech have quite the selection of fairings, and ended up with their AJSM5 three-piece fairing.

Q: Who laid hands on this project, and what were their contributions?

Once I had a sketch to work from, I took it to our assembly line supervisor, Vinnie Falzon, who’s a proficient welder and fabricator. He was instantly excited to be part of the project and ordered material to build the hardtail that day. We bent the tubing using Jeff Sand’s old Hossfeld that was in a container behind the shop. He’s responsible for all the major fab work on the hardtail section, plus the sleek, hand-formed aluminum seat section that he didn’t even start until about two weeks before the bike was to be displayed in Portland. [And, it should be noted, Sand’s design/fabrication chops are massive; he basically invented the step-in snowboard binding at Switch – ed.]

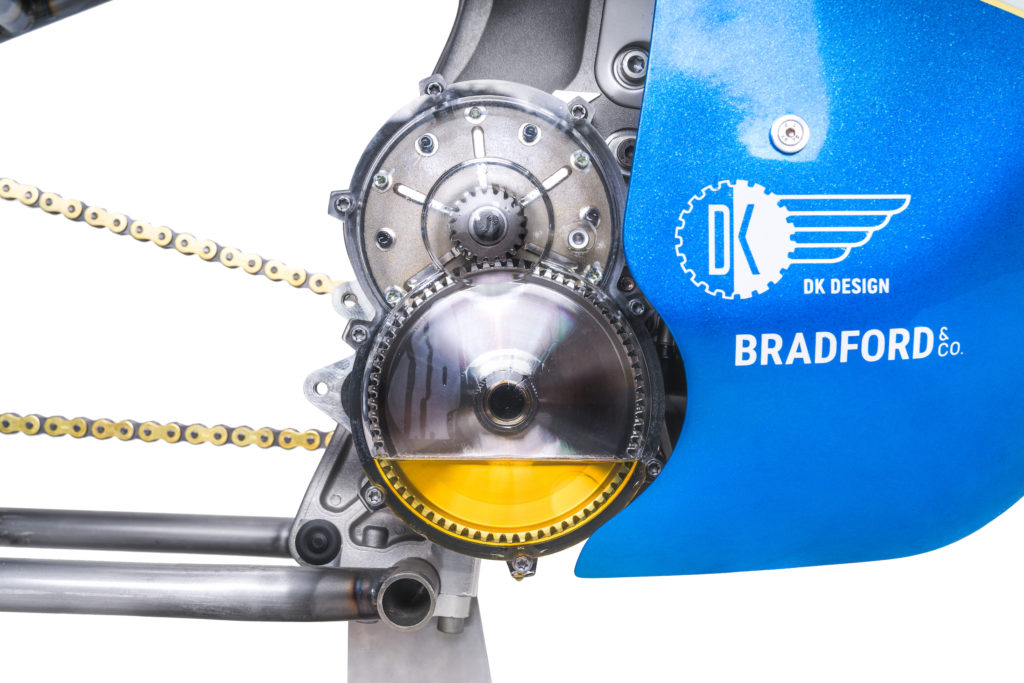

Once I figured out the mounting brackets and trim lines for the body work, I sent the fairing to Dennis Hodges of DK Design in San Francisco, who didn’t bat an eye when I told him exactly how much metal flake I wanted on this thing. He’s responsible for all the clean up work and paint on the fairing, and converting it to a single piece, eliminating the unsightly part line. His accomplice, Jon Bradford, was able to turn our “crapshoot” logo into a sweet decal for the side of the bike.

The seat was a total custom job by Frances Midori, also from SF, who does a lot of work out of Hodges’ shop. We basically dropped off our seat pan and said “make it look like grandpa’s smoking chair” and she totally nailed it. It was the cherry on top for this little retro futuristic period piece, from the future.

Q: How many hours total were invested?

We started bending the tube for the hardtail around the middle of January, and from then until we were doing final assembly in the van on our way up to Portland was nonstop. Vinnie has 40 hours into the seat section alone and I’m pretty sure Dennis didn’t sleep a few days while doing paint and bodywork. There’s at least 100 total man hours into the build.

Related Posts

October 20, 2017

The Current: Mission Motors Electric Sportbike

The Mission One was the most advanced…

I wish I could dream that. I wish I could build that. I wish I could ride that

another POS paper weight… why do they call it a dragster, how about “soy-boy wet dream”