Already the biggest motorcycle auction in the world by a long shot, this year the Mecum Las Vegas auction at the South Point Casino will be their biggest ever, run over six days from January 22-27th. Their sale includes 238 bikes from the excellent MC Collection of Sweden, which includes some of the rarest and most desirable motorcycles on the planet, like a 1925 Brough Superior SS100, several Husqvarna racers, early American machines, and European sports and racing motorcycles too. The full Mecum catalog is here, and it’s a whopper [full disclosure – our own Paul d’Orléans wrote the auction catalog]. This is going to be one hell of a sale, and Vintagent Contributor Tim Huber picked 5 bikes to discuss from the over 1000 machines for sale. Here are some of Tim’s favorites:

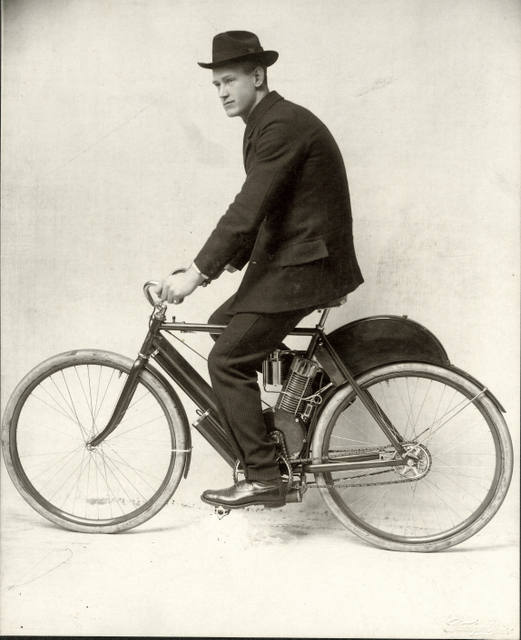

1905 Indian Camelback

What’s today known as the Indian brand first began in 1897, operating under the flag of the Hendee Manufacturing Company. Founded by George M. Hendee, the American outfit got its start pumping out bicycles with names like the “Silver King” and “American Indian” — the latter of which was shortened to “Indian”.

After a couple years of operation, Hendee brought on Oscar Hedsrom in 1901 to develop a gas engine that could be fitted to one of Hendee’s pedal-powered two-wheelers. Later that same year the company opened its first factory in Springfield and introduced its first prototype; a 2.25hp, 260cc (15.85ci) ) “F-head” (inlet over exhaust) single-cylinder engine that doubled as part of the scoot’s diamond frame. The pedal-assisted runner offered a top-speed of around 30mph and utilized a chain final drive.

Dubbed the “Camelback” on account of its rear-fender/fuel-cell/oil-tank combo, the company’s first model went into production in 1902, and remained in largely unchanged until 1906, when Indians got a top-tube tank. Indian outsourced the production of its engines to the Aurora Automatic Machinery Co. (makers of Thor) until it began making its own mills in-house in 1907. The Camelback was a strong seller for Indian, largely because the new single was very reliable, thanks to Hedstrom’s patented spray carburetor design. The model was also popular amongst racers.

Throughout the duration of the Camelback’s production, the Springfield-based marque developed an impressive reputation, with its machines taking part in an endurance race from NYC to Boston in 1902, one year prior to Hedstrom clocking a new world speed record of 56mph. Indian offered its first ever V-twin to the public in 1907, and soon their V-twins would overtake the single-cylinder models in sales, just as with other American makes. 1906 also saw an Indian ridden from San Francisco to New York in 31.5 days, supposedly sans mechanical failure.

Very few Camelbacks left the factory in its first four years of production, and only a fraction of those still exist today, making early examples particularly rare. This restored 1905 specimen is expected to bring in between $85-110K this January.

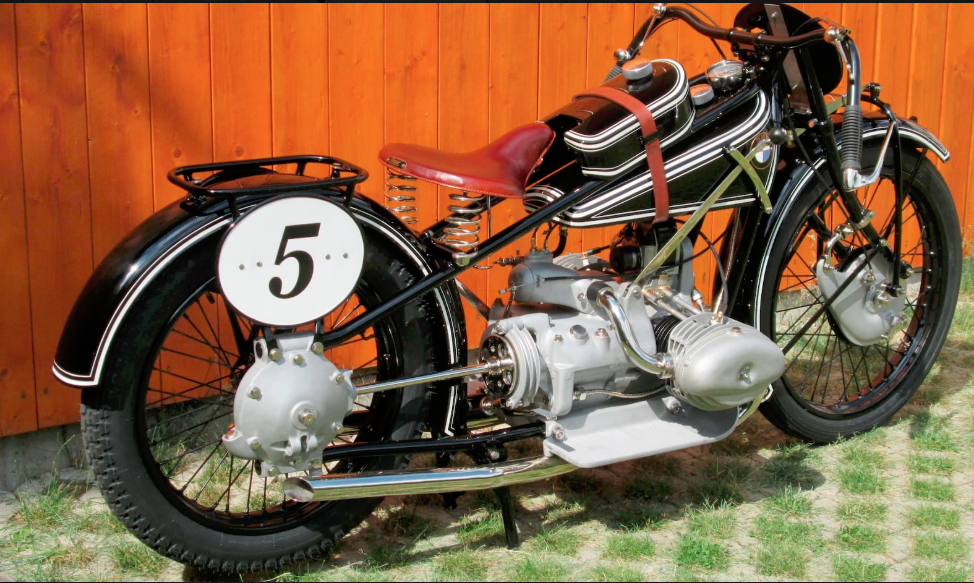

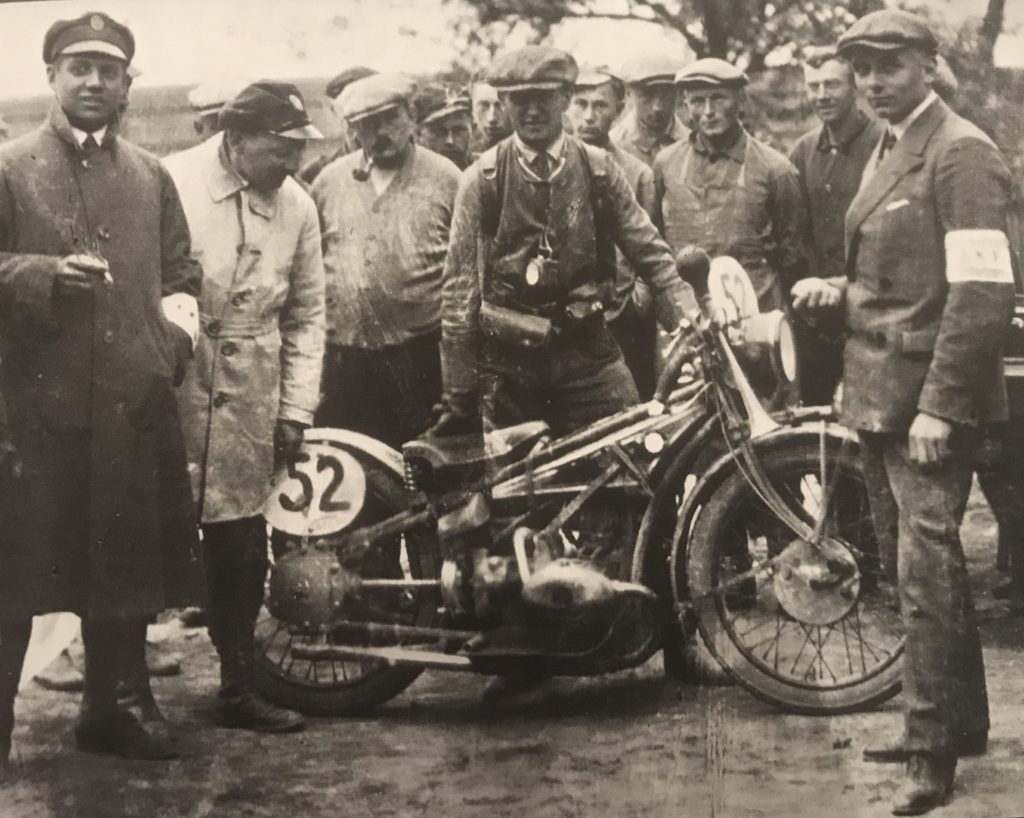

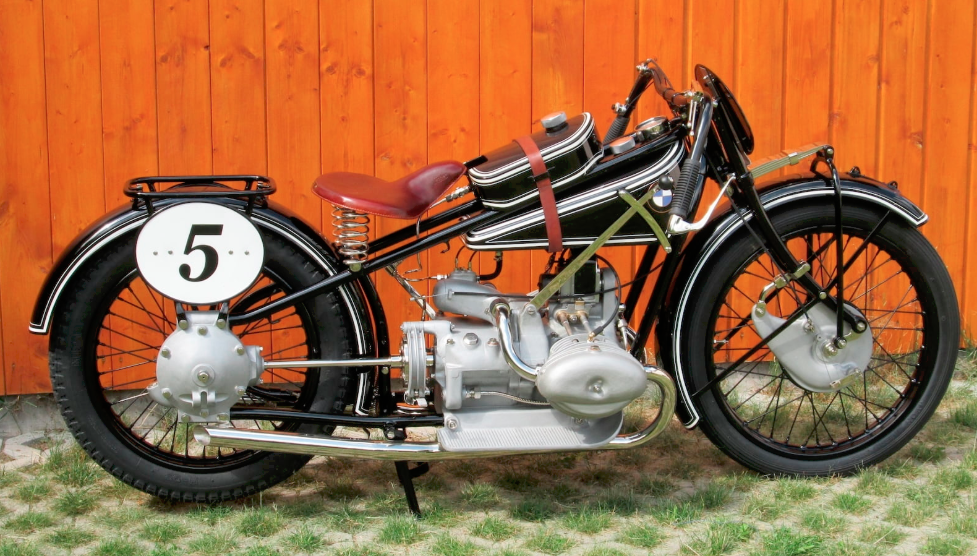

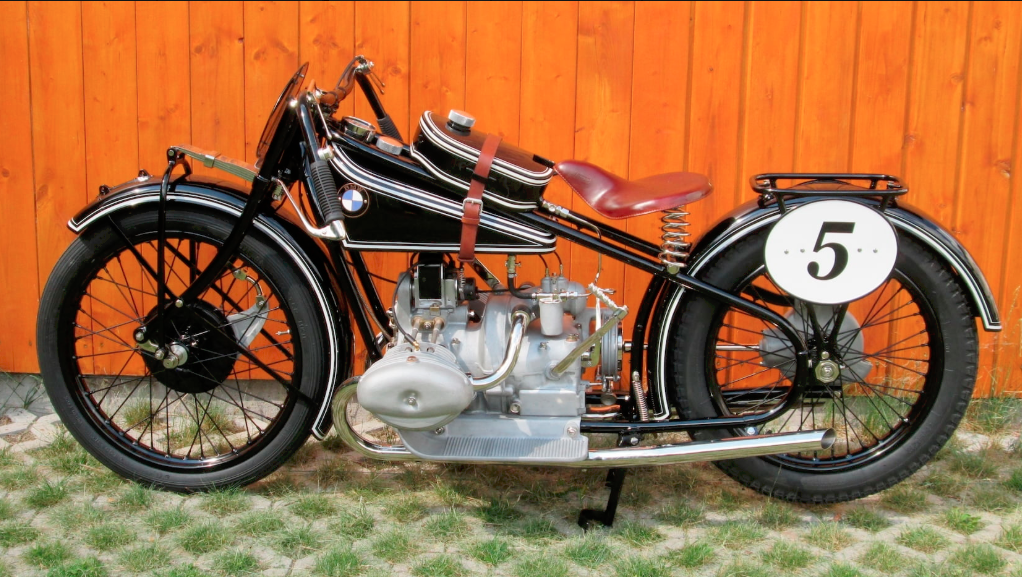

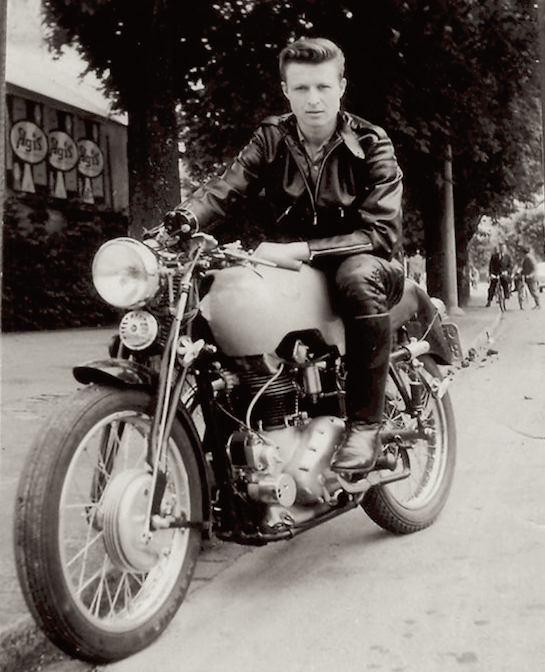

1928 BMW R47 Racer

BMW first got its start making aircraft engines in the First World War, but after Germany was no longer permitted to produce planes or aviation hardware, the company pivoted to building motorcycles (after a less-than-fruitful, short-lived attempt at producing brake systems for trains). In 1923 the Bavarian brand introduced its first motorized two-wheeler, the R32. A truly revolutionary offering in the 1920’s, BMW’s inaugural bike was powered by a 494cc, twin-cylinder, horizontally opposed, four-stroke engine (known as the “Boxer”) — a layout that BMW continues employing to this day.

[Mecum]

The R32 was followed by its higher-spec sibling — and BMW’s first sports model — in 1924 with the R37. Though the R37 was an impressive machine in its time, the suits at BMW knew its relatively exorbitant manufacturing costs were a problem. So the engineers in Bavaria were tasked with delivering a successor to the R37 that was not only markedly cheaper to produce, but one that would also boast superior performance.

The result was the R47. Using the half-liter OHV mill from the R37 as the starting point, the team designed and implemented a new, simplified duplex-loop chassis paired with improved, lighter suspenders in the form of a leaf-sprung trailing-link front fork. A large portion of the electronics were also deleted. In the end BMW was able to bring down the cost of production by more than 1/3 (36% to be exact) without compromising performance — the exact opposite actually. The Boxer’s prowess was a clear reminder that BMW’s former occupation was producing machines that took flight.

The revised engine — which was a lot like the unit found in the touring-focused R42, aside from the loss of the side-valves — made around 50% more power at 18hp (at 4,000rpm) and allowed for a top-speed of around 70mph thanks to its sub-300lbs weight. The powerful engine made the R47 particularly attractive to racers, as did the fact BMW further encouraged the new mount’s competition use by selling it as a barebones model that could be fitted with an array of optional factory parts. This included components such as headlights, generators, and horns for road use, as well as number-plates and a supplementary quick-release fuel-cell for longer races.

Additional highlights on the R47 included a Cardan drive rear brake, a Bosch magneto, a three-speed gearbox and a single-plate dry clutch, and most notably; replaceable bushings, and roller-bearings utilized in the valve rocker arms — supposedly a first. Produced for just two-years in ’27 and ’28 before being replaced by the R57, BMW sold more than 1,700 R47s — reportedly ten times the number of R37s sold by the factory.

The R47 has become one of the most prized and sought-after ‘flat tank’ models from this iconic brand. The Weimar era – after WW1 and before the Depression – was of monumental importance to BMW, with the brand producing (or rather licensing) its first ever car, the 3-15PS (or the “Dixi”) in 1928, a year prior to a BMW motorcycle (piloted by the great Ernst Henne) achieving the world speed record of 134mph (216km/h) in ’29 on a public highway outside Munich. This particular 1928 R47 racer is in immaculate condition and features a number of period-correct options, including the extra quick-release fuel-cell.

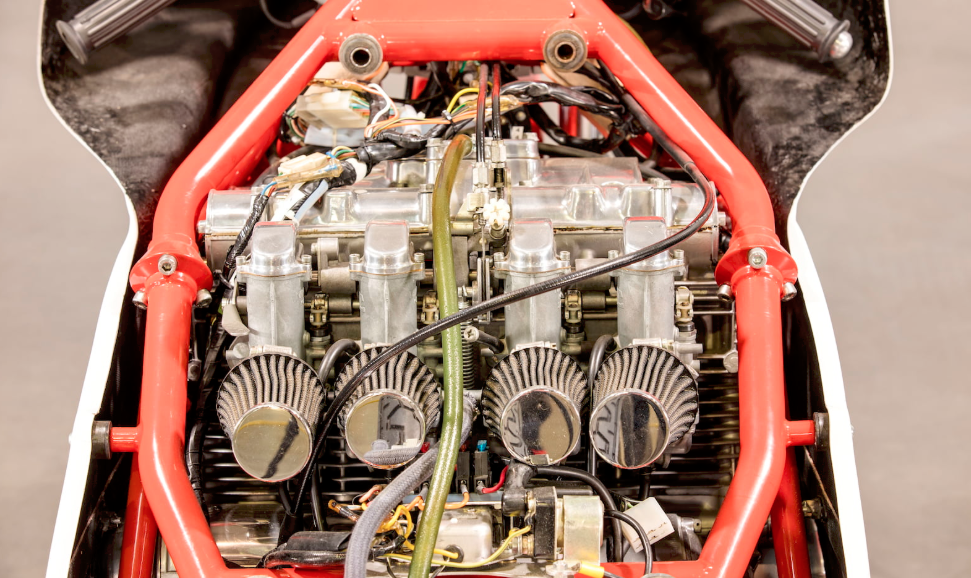

1980 Bimota SB2

Not unlike the speed wars of the 1990s, in the 1970s the motorcycling industry experienced a pattern of engine design greatly surpassing that of chassis technology, at least among the Japanese manufacturers dominating the business. While the first generation of Japanese fours were plenty fast, they seldom possessed adequate frame rigidity, suspension damping, or stopping power to accommodate their increasingly potent power plants. This inspired three motorcycle enthusiasts in Italy to form Bimota, to create cutting-edge frames to house Japanese engines, which were than outfitted with a smorgasbord of equally trick components.

The first model from the boutique manufacturer was the Honda CB750-powered HB1 (or “Honda Bimota 1”) in 1973, and less than a dozen were built. Despite their tiny production, the HB1 gave this Rimini-based outfit a reputation for building first-rate racing chassis, with exceptional build quality. Two years later Bimota unveiled another production racer, the Suzuki TR500-based model ‘SB1’ at the 1975 Milan Motor Show.

At the 1977 Bologna Motor Show Bimota debuted its first road-legal motorcycle, the aggressively sexy SB2. At the heart of the new model was Suzuki’s GS750 mill wrapped in an ultra lightweight chromoly trellis frame. Its DOHC motor was a stressed frame member, and the frame featured an adjustable steering-head angle. The three-quarter-liter engine had been bumped up to 850cc, and was hotted up with Yoshimura pistons and cams, and the SB2 generated 78hp at 8,700rpm, 42ft-lbs of torque at 8,250rpm, and boast a top-speed of 135mph, making it one of the fastest motorcycles in the world.

The trick frame — which only weighed around 20lbs — was paired with race-spec 35mm Ceriani forks up front and a Corte & Cosso monoshock out back. Braking duties were bestowed upon a trio of Brembo discs married to lightweight magnesium alloy, gold anodized, Campagnolo rims. The SB2 also got brake caliper mounts, fork yokes, and rear-set brackets machined from billet aluminum. Weighing in at just 432lbs, the SB2 was a whopping 66lbs lighter than the stock GS750, though the lightness (and all those top-shelf parts) didn’t come cheap: the SB2 sold for a cool $4,000, (a figure that translates to just over $17K today with inflation) approximately triple the price of the stock Suzuki.

Undeniably the most eye-catching aspect of the SB2 is its sweeping and curvaceous bodywork. The unapologetically 1970s, Tamburini-designed bodywork was made up of a one-piece tank and tail section comprised of aluminum-lined fiberglass, with a removable 3.4 gallon inner fuel-cell. The design originally planned for the exhausts to exit via the tail, though testing revealed that this layout generated too much heat, negatively affecting carburetion: it was decided to run a low-hanging four-into-one system instead. However, instead of redesigning the exhaust ports on the tail, Tamburini opted to use the recesses for the SB2’s rear indicators.

While its performance might not sound that impressive by today’s standards, upon its release, the SB2 was some serious next-level machinery, and the fact it just happened to be adorned in some of the sexiest bodywork of the decade was just the icing on the cake. This particular 1980 example was last ridden in ’84, before being expertly restored in 2012. One of the 140 SB2 units to leave the factory in Rimini, this exact example bears the nickname “The Blix Gordon” and currently resides in the MC Collection of Stockholm, though it’s expected to fetch between $29-36K come its turn to cross the block in January.

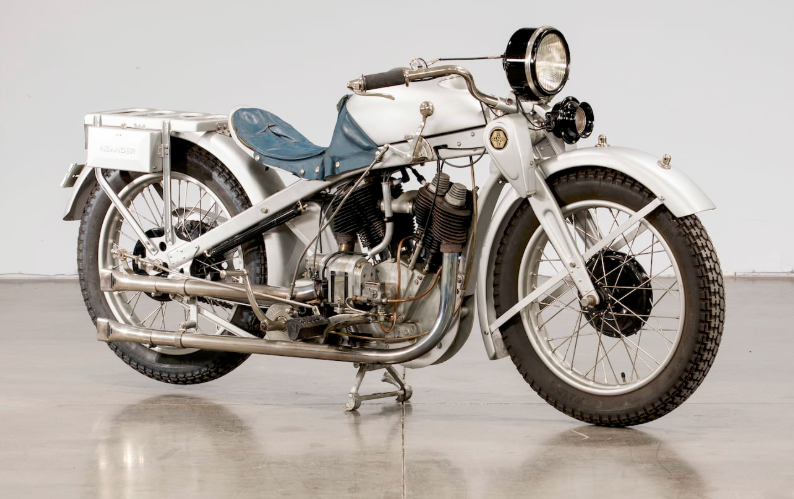

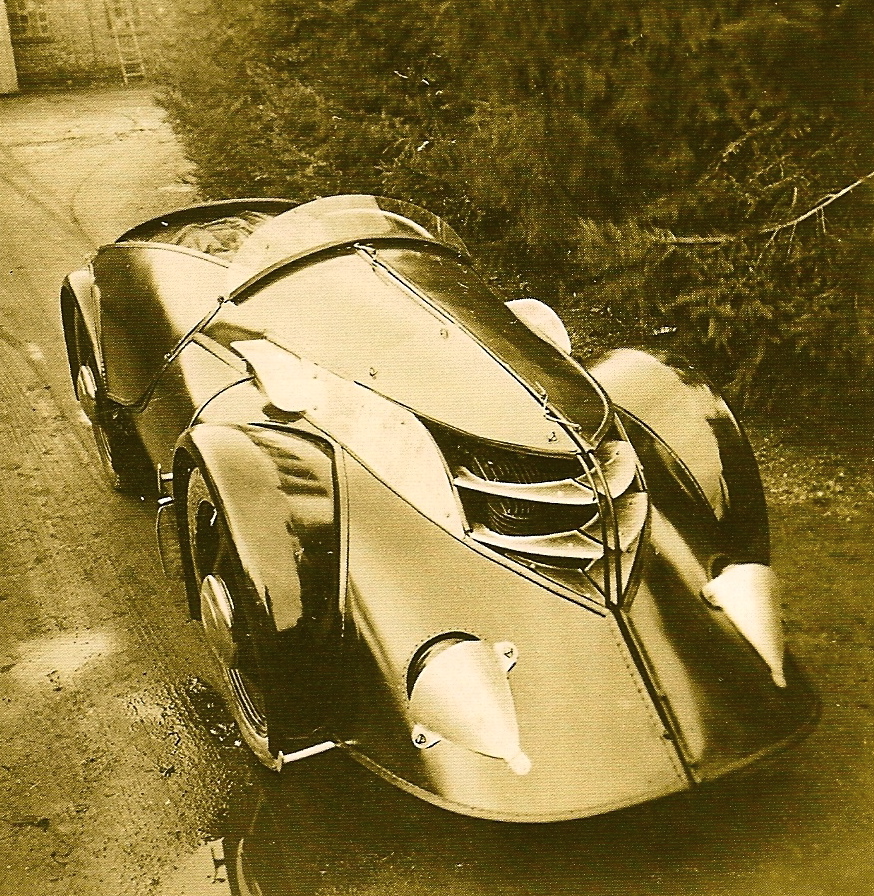

1929 Neander-JAP V-twin

Born in 1871 in the Prussian city of Kassel, Ernst Neumann-Neander trained as an artist in Germany, and moved to Paris in 1903 to pursue his art. While there, Ernst befriended a number of major players from the rapidly emerging auto industry. Son of the famous sea and landscape painter, Emil Neumann, Ernst relocated to Berlin in 1908 where he started his own studio, “Ateliers Neumann”, where he designed Art Nouveau-style posters and advertisements for car companies, though it didn’t take long for the German to shift his career focus from marketing vehicles, to making them.

Neumann had reportedly been tinkering with motorcycle design largely behind closed doors for around 20 years, building a steam-powered tricycle concept in the late 1800s (hipsters, eat your heart out) before officially starting his own marque. His first foray into vehicle design was penning coachwork for noteworthy companies like Szawe, Schebera, and Rolls Royce. With time, Neumann’s work on wheels became his primary focus, and in 1924 he moved to Euskirchen (an hour south of Cologne) where he founded the Neander Motorfahrzeug GmbH. He also took Neander as his last name, which is Greek for ‘new man’, as our Ernst was a Utopian visionary, who believed technology would transform human life.

Motorcycle chassis technology had come a long way since the introduction of the motorized two-wheeler, however there was still plenty of room for innovation as far as Ernst was concerned. In place of the standard structures of the day the former artist assembled a complex riveted box-section frame design comprised of duralumin — an aluminum and copper alloy invented in 1903 by fellow German, Alfred Wilm — plated in cadmium. Though the lightweight metal was primarily utilized by the aviation industry, Neumann felt the trick new material had properties that would lend themselves well to motorcycle frames.

The new channel-section frame design boasted superior performance capabilities, being light and resistant to corrosion. As it was rivetted together and could be assembled from prefabricated parts, production time for the frame was reduced fivefold, from around 20 hours to less than four. Up front, Neumann used a relatively sophisticated suspension setup of his own design, with a pivoting leaf-spring setup, and with the unique spring boxes located at the steering head. As demonstrated by the Neander’s success in competition, when wrapped around the right engine, the Neander frame design made for a particularly competent racer — a fact used to market the unique machine during its short-lived production run.

The Neander Motorfahrzeug introduced the new frame design on a range of models, with a number of smaller bikes powered by 175cc Villiers two-strokes, and several bigger singles and V-twins (as large as 1,000cc) from companies like JAP, Motosacoche, and Küchen. The Neander’s innovations and racing success brought industry attention, and in 1928 Opel licensed the Neander design, which was sold as the Ope Motoclub, and built until the company ceased motorcycle production in 1931, when Opel was acquired by American auto powerhouse, General Motors.

The Neander’s innovative frame and front-end made it an attractive offering — as Paul learned when he test-rode a JAP-powered Neander in the mountains of Bavaria — but furthering the model’s desirability was its distinctive appearance which undeniably benefitted from Neumann’s background as a formally trained painter and sculptor. The model sported an body-hugging saddle protruding from a surprisingly modern-looking fuel-cell — both of which were incredibly ahead of their time aesthetically and a major departure from the elongated, tear-drop style tanks and bicycle saddles of the day.

At the dawn of the next decade as the world reeled from a global financial crisis, Ernst Neumann-Neander began developing his vision for a ‘people’s car’ – a utilitarian, no frills, vehicle for the everyman. He developed a series of Fahrmaschinen (Driving Machines), which were small cars with an interesting leaning/tilting chassis, that had excellent performance. But setbacks like exorbitant production costs, a lack of interest from the public, and the machine’s unorthodox nature meant only about 20 were built before the plug was pulled on the project, on the outbreak of World War Two.

In the end about 2,000 Neander motorcycles left the factory, plus the Opel models built under license. Neumann-Neander passed away in 1954 at the age of 83, having pursued his vision and successfully produced his idiosyncratic machines, which today are coveted by collectors. This particular Neander is fitted with a JAP 1,000cc, V-twin sidevalve K-series engine, married to a hand-shifted three-speed gearbox, and a Bosch magdyno. Currently part of the MC collection of Stockholm, this 1929 example is all original, even still wearing its leather tank wrap, knee-pads, and pouch/pocket, rear-luggage, and lighting from the factory. This rare museum-worthy survivor is expected to bring in between $50 and 65K when it crosses the auction block next month.

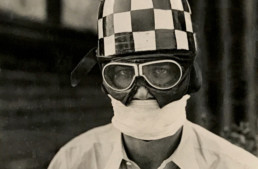

1948 Egli-Vincent Cafe Racer

Like several other examples on this list, Vincents were ahead of their time in myriad areas, and their well-developed engines held the distinct honor of being the most powerful mills in the world from ’36 to ’73, though their “frames” left something to be desired over the years. Many racers — including John Surtees — attempted to get around the frame’s limitations by dropping the robust V-Twins into a more capable chassis. One racer (and engineer) from Switzerland, Fritz Egli, created his own chassis in 1967 that employed a large tubular backbone unit (welded together, not bolted) that functioned as the oil-tank in addition to the main structural member.

Despite the Egli’s engine being more than a dozen years old, the excellent frame, when combined with top-of-the-line running gear, resulted in a terrific racer. In 1968 an Egli-Vincent won a prestigious European hillclimb event, and that same year Egli kicked off micro-batch production. Supposedly only around 100 original Egli-built Vincent were ever built, making them wildly hard to find.

After Fritz quit building motorcycle chassis, a talented Egli-Vincent enthusiast, Patrick Godet, started reproducing the Swiss-framed, British-powered icons. Godet’s expertise made him the only person to receive Egli’s official blessing to recreate his chassis. The Frenchman spent decades building officially licensed Egli-Vincents to order. Godet sadly passed away only a few weeks ago, so the fate of his company is unclear.

This particular Egli-framed 1948 Vincent cafe racer is propelled by a genuine Series B Rapide engine and shows only 2,352 miles on the clock. The Series B Rapide was the new engine design introduced after World War Two by Philip Vincent and Phil Irving, improving on their already famous Series A Rapide. The new Vincents went on to bag win after win in numerous competitions and classes, including Rollie Free’s famous 150mph Bonneville speed-record in ’48.

Expected to fetch between $60 and 80K, this cafe’d Egli-Vincent sports a knee-dented tank, cafe fairing complete with headlight bubble, machined rear-sets, velocity stacks, disc brakes fore and aft, two-into-one pipe, and clip-ons, amgonst other highlights. Part of the MC of Stockholm collection, this gorgeous two-wheeler is adorned in a royal blue livery with silver stripe and genuine Egli-Vincent badges and is one of the raddest cafe racers in the world.

For more info on Mecum’s 2019 Las Vegas auction you can check out this full-length preview/promo video for the MC Stockholm collection, or click here to view all 52-pages of the auction’s lots.

Related Posts

December 21, 2018

The Vintagent Selects: The MC Collection Of Stockholm // Mecum Las Vegas Motorcycles 2019

This is the MC Collection.

May 25, 2018

A truly mouthwatering selection. The Bimota SB2 is my pick, although it’s worth noting that the Laverda Jota was actually the fastest production bike at that time. I believe it was clocked at around 145 mph in contemporary tests.

Thanks Chris – agreed about the SB2, what an amazing piece of kit, and the best looking four for years. Noted about the speed:

will amend.

Respect and appreciation once again for the engineering and design master behind the SB2- Massimo Tamburini. Notice that the frame is wrapped so tightly around the engine, that there isn’t even room for the four original chrome round cam end covers. A small detail that shows how serious and single minded this design is. Italian design and styling icon.

Looking forward to hearing your broadcast commentary and insights again, Paul.