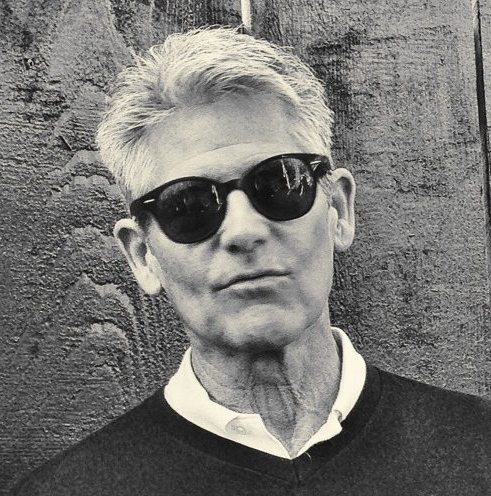

Book Review by Charles Fleming

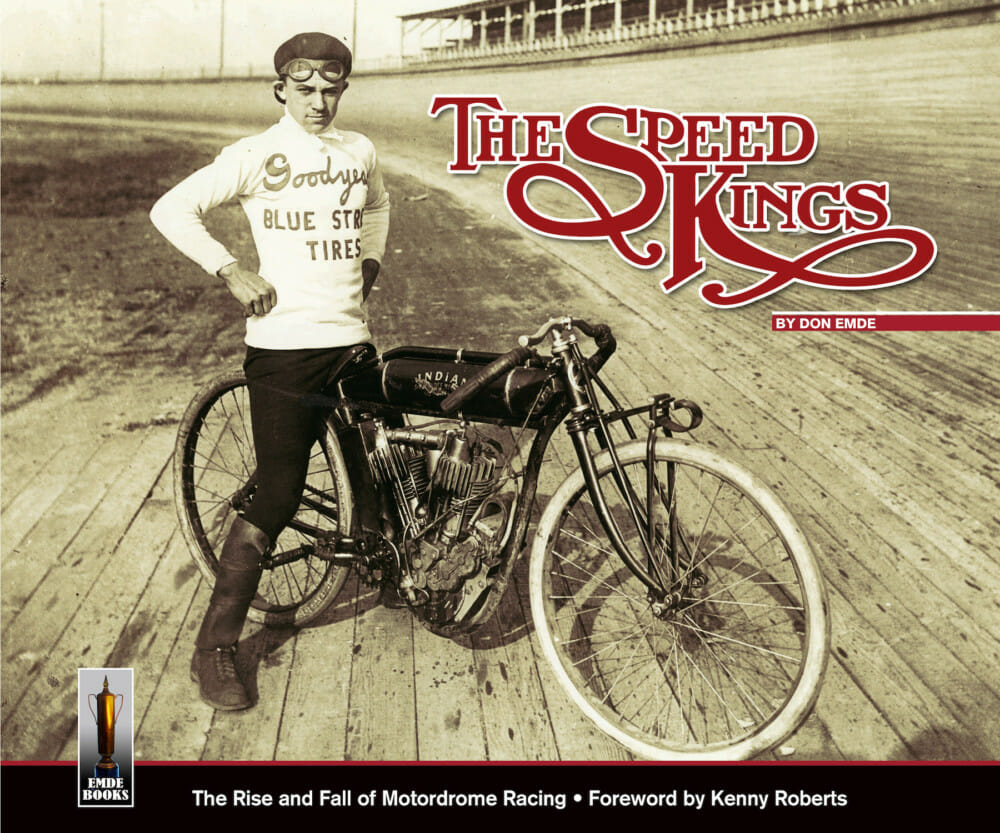

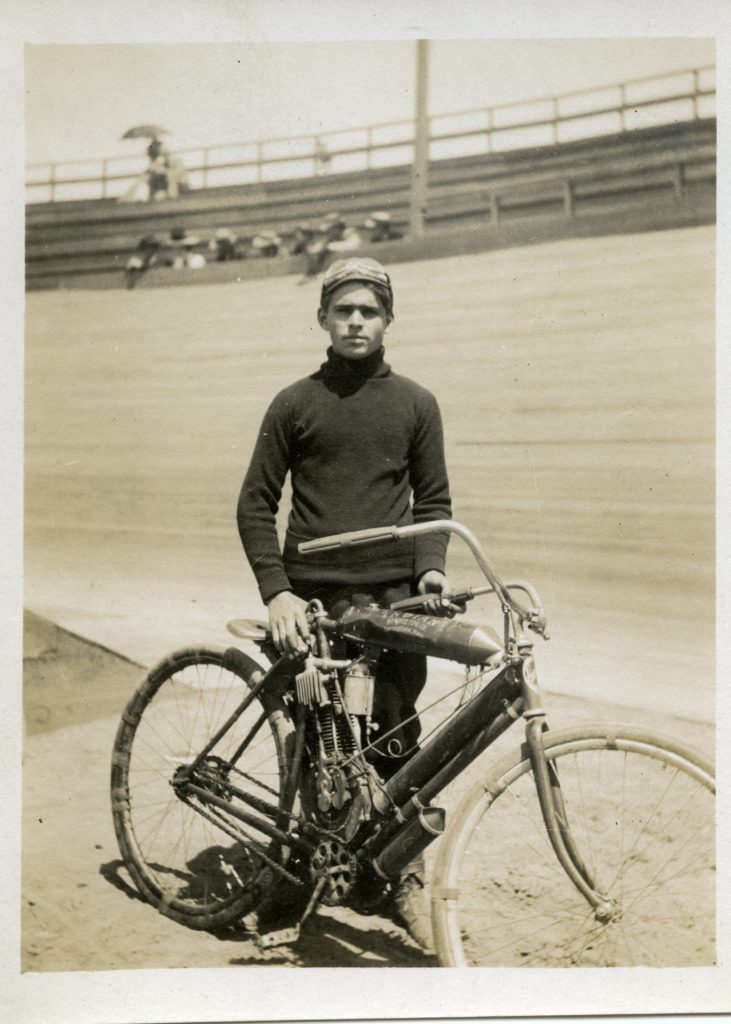

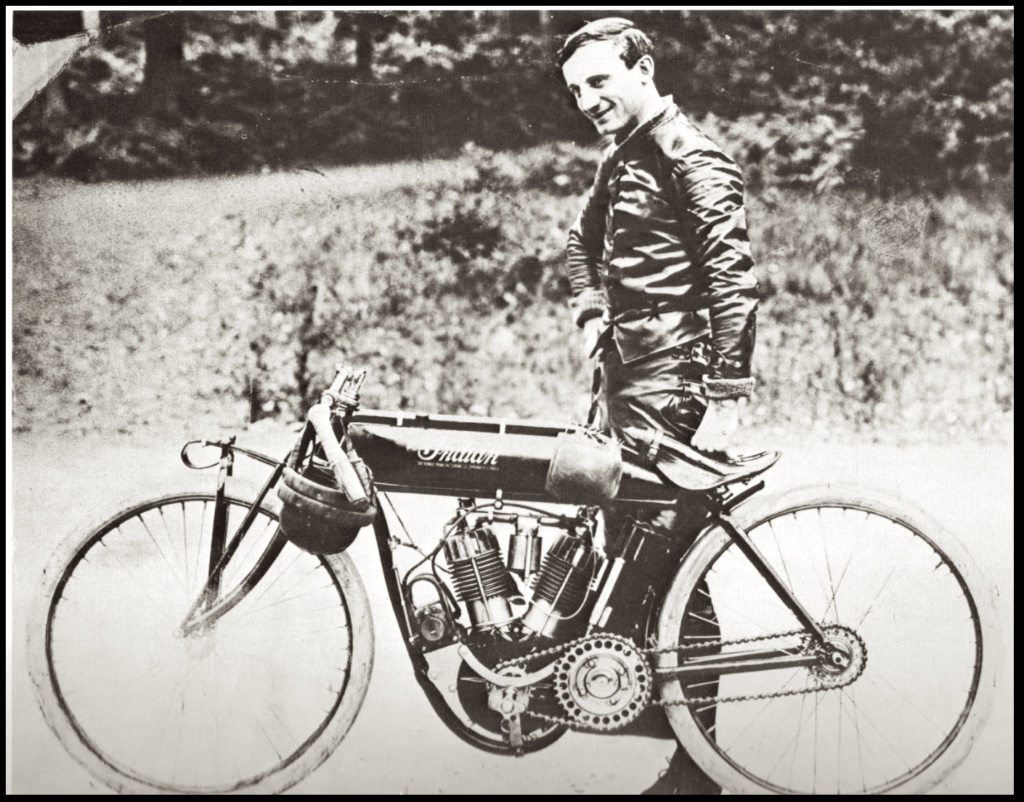

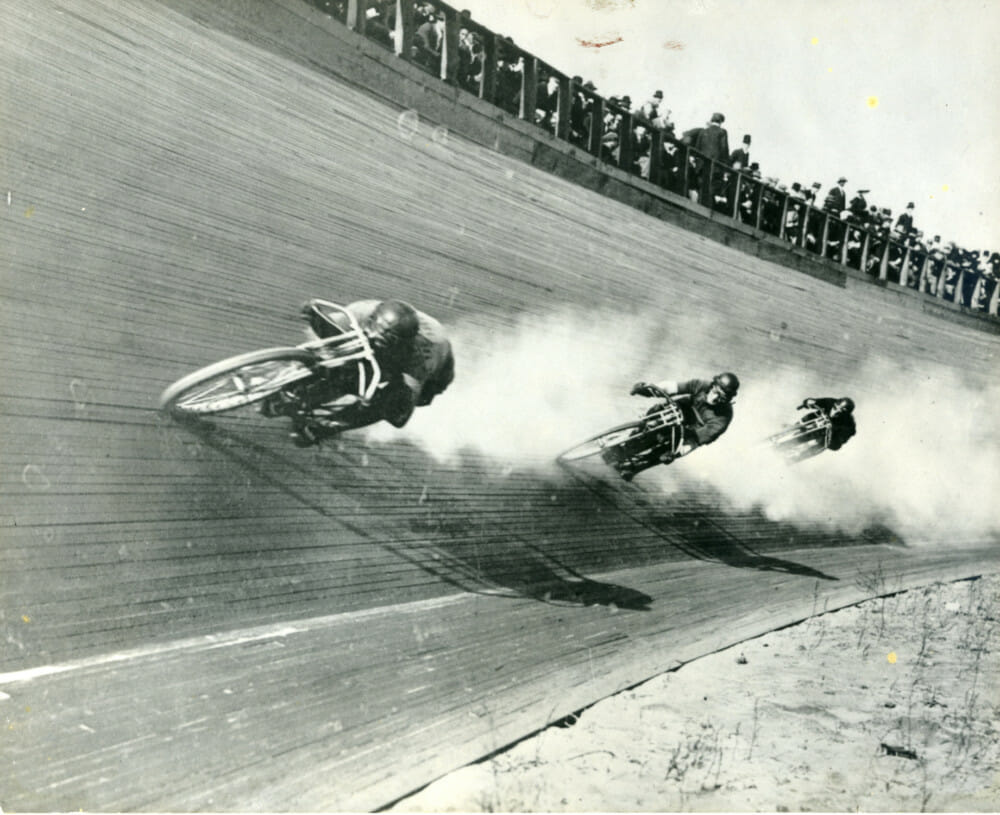

In his expansive new book ‘The Speed Kings’, motorcycle historian and Daytona 200 race winner Don Emde has chronicled the meteoric rise and tragic fall of American board track racing, which at its peak in the early 1900s rivaled baseball as America’s number one spectator sport and made its champions into the country’s first national sports heroes. Emde spent four decades collecting images and information on “motordrome” racing, which flourished in the U.S. between roughly 1909 and 1914, ultimately compiling 6,000 pages of data. From this he has created a dense, oversized coffee table book, massive in scope and weight, packed with the ephemera of a bygone era. Included are more than 600 photos.

An extremely well written and designed book. The photographic reproduction are first class.

If you want to know about board track racing this is the book.