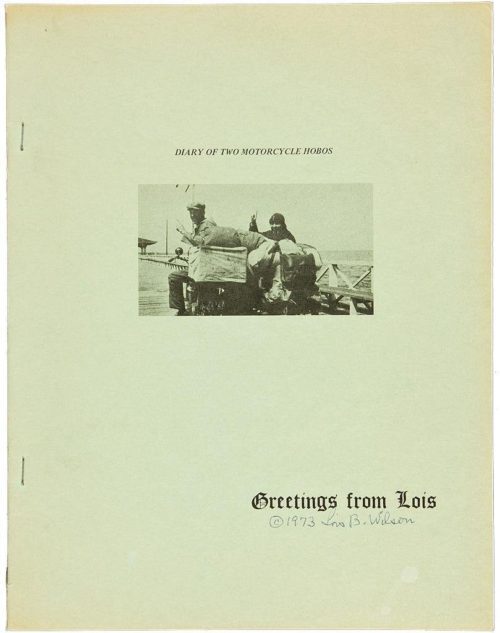

Forced occasionally by bad weather to pay for food or shelter, despite their best efforts to camp wherever possible and feed themselves by fishing and foraging, the Wilsons were soon out of funds. In July, they found a farmer who was willing to take them on as summer help – Lois cooking and cleaning, Bill repairing farm equipment and doing general labor. Through the fall and winter they were back on the road, fighting the falling temperatures with a newly-acquired windshield for the motorcycle and a mattress and hot water bottle for the sidecar. Bill continued to visit cement factories, electric power plants and other companies – even getting invited to a private display of the new cinema development known as “talking pictures” – while sending reports back to his friends on Wall Street. One was sufficiently impressed to send the Wilsons some much-needed money.

Lois’ plan to keep Bill sober was only moderately successful. She managed to keep Bill away from the bottle for weeks at a time. But whenever alcohol was present, and he took a drink, extreme drunkenness followed. One time he stepped away from Lois saying he needed cigarettes, and did not return. Left alone on the street, with no money, in a strange town, Lois waited for hours until, well after dark, she began to search from one barroom to the next. “At last I found him, hardly able to navigate–and the money practically gone!” she wrote. Bill’s plan proved more effective. By the time he’d finished his tour of the east coast, he had convinced backers on Wall Street to invest in his companies and bankroll his own investments. Soon he and Lois were back in New York, living like royalty. “For the next few years fortune threw money and applause my way,” Bill said later. “I had arrived.”

Related Posts

February 14, 2018

The Vintagent Selects: Josh Kurpius DKS! Harley Davidson Ambassador

DKS! went to Milwaukee, WI. to meet up…

June 14, 2017

I like him even more now after reading that story!

I love this write up! I appreciate hearing the details of the motorcycle part. I have been researching Bill & Lois as I have a personal connection. My Grandfather was close friends with Bill and Lois, Not in the AA sense, but my GF became friends with Bill in WW1, The truth is Bill had extreme PTSD which no one truly understood back then,. After the war they stayed in close contact. My GF went to work in the oil business. Its a LONG story, but I have some of their personal letters and a first edition of the AA book with inscription to my GF and his wife. When Bill died my GF was a guest speaker at the funeral and clashed with the AA folks who sought to define Bill by his alcoholism. My GF fiercely opposed that and told them to get stuffed. Clinically I agree Bill was an alcoholic, but my GF did not believe that. I have contacted the organization but they have been somewhat perplexed to hear any of this and stick to the party line. But while I am not a alcoholic, I have been thinking how to share this unique chapter in his life as well as I figure the AA folks would like to see my original book and material. My Grandfather was Phillip Towsley, Army Aeronautical div and graduate of Berkeley Aeronautical university in 1918 and I still have his grad certificate and his pilots wings. As a USAF veteran I am proud of my Grandfathers service as well as my fathers in WW2 and Army Air Corp. However despite surviving WW1 as a fighter pilot, My GF always said his greatest accomplishment was surviving the 1918 Flu epidemic, Not the war which has added symbolism these days! And oh yes, Grandpa had a Harley as well, Sure wish we still had it! Sold it during the depression.

What a fantastic story! And worth telling. And, to a hammer, everything looks like a nail, and while the AA folks have a very successful treatment system (the most effective long-term I understand), others may see it as a symptom not a disease. An understanding of PTSD would give nuance to Bill’s drinking: ironically today therapy with psychedelics has been very effective at treating PTSD. The symptoms related to PTSD (self-medication) tend to disappear as the disease is mitigated…so perhaps your grandfather was right. He certainly knew Bill better than a lot of other folks.

Got any pix of your Grandpa and his Harley-Davidson?

Thanks for another perspective on Bill Wilson. As for alcoholism, it’s a self-diagnosed malady (according to Bill Wilson). The steps of AA get down to what he termed “causes and conditions.”

He also called himself an “ex problem drinker.” You probably know this. It in no way diminishes his good friend’s (your GF) perspective. My Dad’ described his drinking after WW-II self-medicating his shell shock. One day around 1951, he looked at a glass of vodka he was drinking with his lunch, declared himself done drinking and he was.

He met my mother shortly after and married her. I’m the middle of 5 of their kids. When the time came for me to quit or lose my marriage and family, 4 children, I couldn’t stop like my father could. AA helped me by only after the marriage ended. I found the AA fellowship 36 years ago and never drank again. Bill’s method worked, still does.