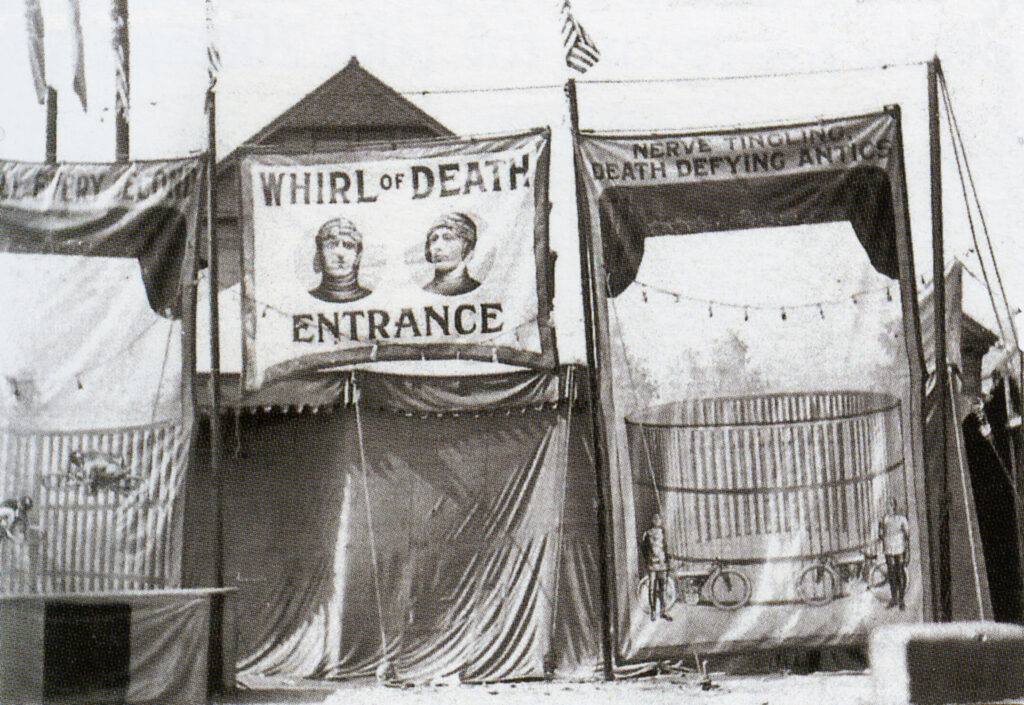

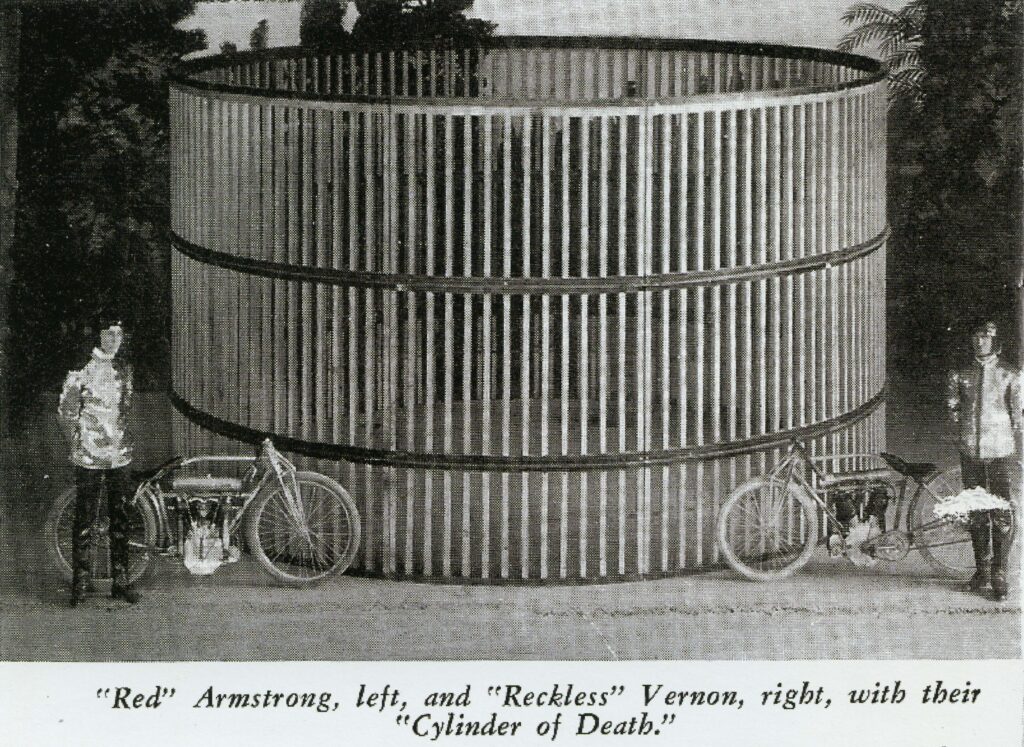

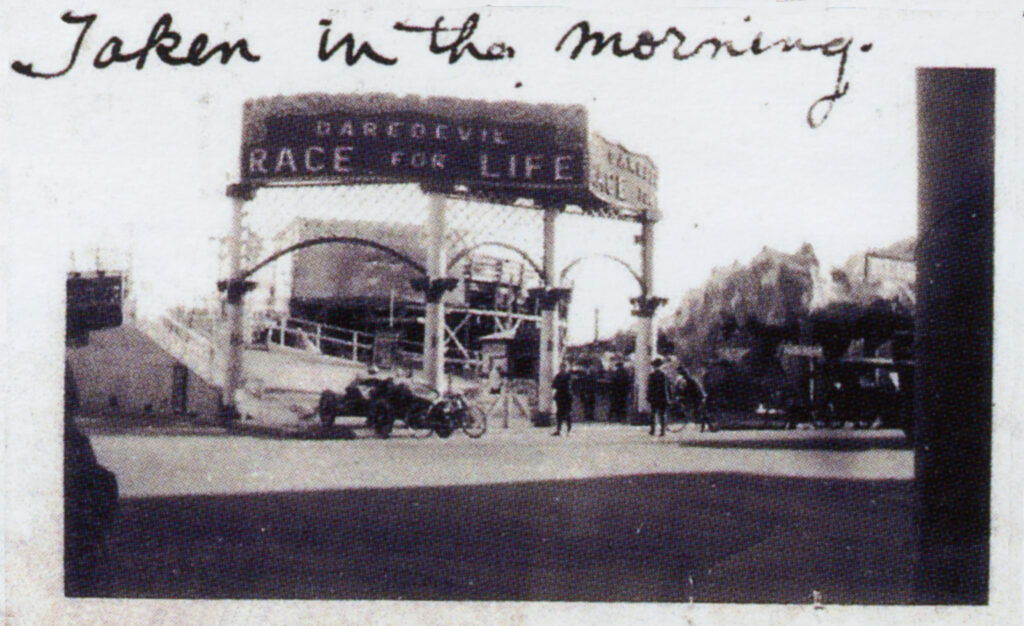

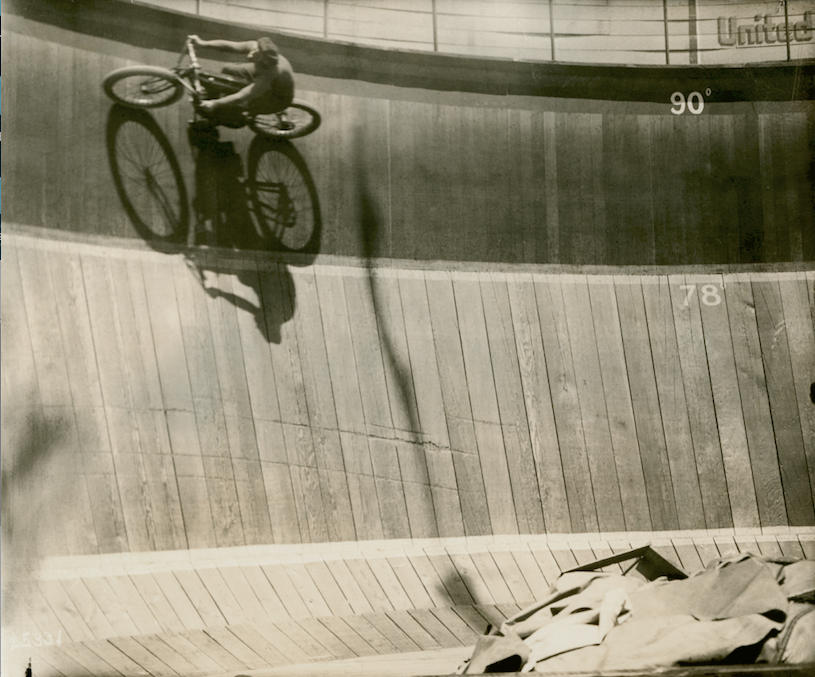

“A wooden cylinder with spruce slats three inches apart, 19 feet in diameter, and 12 feet high, two 61 cubic inch ‘ported’ motorcycles, and two daredevil riders attired in spangled costume, were the ingredients of one of the most hair raising vaudeville acts ever to tour the old time ‘three a day’ circuit. Conceived in the brain of ‘Red’ Armstrong who was also one of the performers, this act toured the top billing of the country in company with such greats of the theater as Eddie Cantor, and Weber and Fields.”

“The act consisted of riding the inside of the cylinder – with two riders going in opposite directions – blindfolded! Traffic was controlled by a ‘ringmaster’ who sounded a shrill blast on a whistle if the top man approached the open apex of the cylinder, and two blast if he came too low. This early day ‘sonar’ system worked out fine until one night in ‘Frisco when the whistle failed! Red remembers riding right out of the top of the contrivance, and soaring off into the wings in an unscheduled exit! He was right back in the next performance despite a somewhat damaged big toe – his only souvenir of the accident.”

It’s amazing how long these things … with slight variations have lasted .

Growing up in NJ spending mis summers in Wildwood [ when not on Plum Island or Martha’s Vineyard MA back when Plum Island was still just a fishing village and MV was barely much better ] the Wildwood ( or as my Italian great grandmother called it … WildaWoods ) ‘ boardwalk ‘ had both the wall of death for the motorcycles … and …. the hell hole for the rest of us …. where the ‘ hole ‘ spun while you remained stationary … and when the thing reached a certain rpm … the floor went out from beneath you . The real trick being ( if you were light enough which I was ) was to raise your leges well before the floor lowered … giving you an extended experience of the thrills of centrifugal force . …. giving you a small taste of what wall of death motorcyclists were experiencing .. right next door

Sigh …… the joys and experiences of being the old guy that todays youth will never comprehend … never mind experience

Rock On – Ride On – Remain Diligent and Calm ( despite all the rhetoric and BS ) .. and do Carry On .. despite the currently plethora of digital gremlins running loose …

😎

During my Midwestern yute in the late 60’s the Wall of Death was still a regular at the county fairs. I remember one in particular that had a stripped down Tiger Cub with a straight pipe mounted on the platform facing the Midway, they would fire it up periodically to lure the rubes. It certainly worked on me! I just reviewed the awesome WOD sequence in Roustabout, what a period document of the whole thing!

Hi Greg,

‘Roustabout’ is fantastic! Plus, there’s ‘Eat the Peach’, an 1986 Irish film all about a Wall – we have the trailer here: https://thevintagent.com/2018/05/26/the-vintagent-classics-eat-the-peach-1987/