Toru Tokikawa’s new film, Sparks and Speed: The Story of Shinya Kimura, displays its ingenuity in a lyrical and poetic portrayal of the master custom bike builder, Shinya Kimura. But the film almost didn’t happen. Toru first approached Shinya with the idea for a reality show. Shinya wouldn’t do it. He told Toru it wasn’t representative of who he was. It took six years, some deep thinking and bravado for Toru to approach Shinya again with the concept of filming the building of a custom bike from start to finish. Shinya gave him the green light. What transpired during the three years of filming was less a process film but instead a moving portrait of the depth of human connection and its intersection with artistry and functionality.

Vintagent Contributor Nadia Amer conducted an interview with Toru Tokikawa, Paul d’Orléans, and herself, which she has condensed into the following exchange:

Paul d’Orléans (PDO): Hi Toru. Thank you for speaking with us today. When did you first hear about Shinya and how did that encounter come about?

Toru Tokikawa (TT): My father-in-law had a friend who had a Zero bike [note: Zero Engineering was Shinya Kimura’s custom motorcycle business in Japan, with no relation to the eBike company in the USA – ed.]. We lived in Okazaki, Japan and so we knew exactly where the Zero factory was. When he heard that I was moving to LA, he said I know a guy who’s a world famous bike artist and since you’re a filmmaker, you should definitely meet. So the first thing I did when I arrived in LA was to go see Shinya.

PDO: Were you born in Japan?

TT: Yes, but I grew up in Berkeley, Jakarta and Tokyo. I moved to LA in 2011 – that was the year I met Shinya. Shinya had moved to the States in 2006.

TT: Yes. I’m a filmmaker so if there is something interesting, yes, of course, but it’s a bit of an embarrassing story. It was my first time to see his work and in his workplace studio, there was less stuff than now, but he already had the mezzanine. It was like a little museum of his sculpture rather than the motorbike. Downstairs he had the work-in-progress custom motorcycles. For me it was unexpected because I assumed it would be a garage doing chopper stuff, modifying with commercially available parts! But his work was really like sculpture and totally unique, original and hand-crafted. I wondered if these bikes could actually run. He told me yes, you can ride them. He told me he liked going for long rides in the canyon behind his shop, through the desert and natural parks.

I pitched an idea for a reality show where Shinya Kimura rides in the Arizona desert, and goes to Sedona and gets inspired. My first thought was that looked like he fit into that environment. I created a pitch deck for the idea, which I presented to him, and the first thing he told me was, ‘You don’t understand me’.

PDO: Wow, what feedback!

TT: It was hard, but very honest. He told it like it is, ‘This has nothing to do with me. I won’t do it.’ And that was it. That was the end of the conversation. But I kept thinking about it. Who is Shinya Kimura and what does he really do? What is the real nature of this artist? I thought about it for six years and the second time we met, we talked about this documentary.

TT: No, for me, his rejection was kind of brutal. It was like, don’t come back.

PDO: So what happened in those six years that helped you understand him better, so you could make an approach for a film that was acceptable?

TT: I reflected on myself, and realized the pitch I presented was kind of rude because I was just looking at the surface. I wasn’t looking at him on a deeper level.

PDO: So he was right.

TT: He was totally right . Even as I speak to you now about the stupid pitch, it’s quite embarrassing for me, but that’s the true beginning of our encounter.

PDO: Well, your film is about his process, and this conversation is about your process. So it seems to me that was an important step in your evolution in approaching Shinya and understanding him.

TT: In between those meetings I made a couple of feature documentaries, and I also learned quite a bit. I pitched this new approach, a new angle to depict who Shinya Kimura really is. He said, ‘Okay, maybe we can start filming and see what happens.’ It was October or November of 2017 that we started. It was a test shoot and we didn’t know where that would go. So we just filmed him riding in the canyon and a small scene of him working on a Harley-Davidson.

PDO: Right. There’s film of him working on the Knucklehead. He’s built a couple of Knuckleheads, one for land speed racing, but it was the other one with a little brown tank. So how did the Moto Guzzi come into the picture?

TT: It was by coincidence actually. At the time, Shinya didn’t know what his next bike would be. We thought it would be an easy and practical approach to film the process of making a custom motorcycle from A to Z. And in January, 2018 the Moto Guzzi project just popped up. So I told Shinya this is a good chance for us to start filming this process. He agreed and that’s how we started.

TT: He told me that when he finishes, it’s the end of the process. There’s no deadline. He feels fortunate to have clientéle that understand his process, so he can be free to focus and devote himself to finalizing his customization.

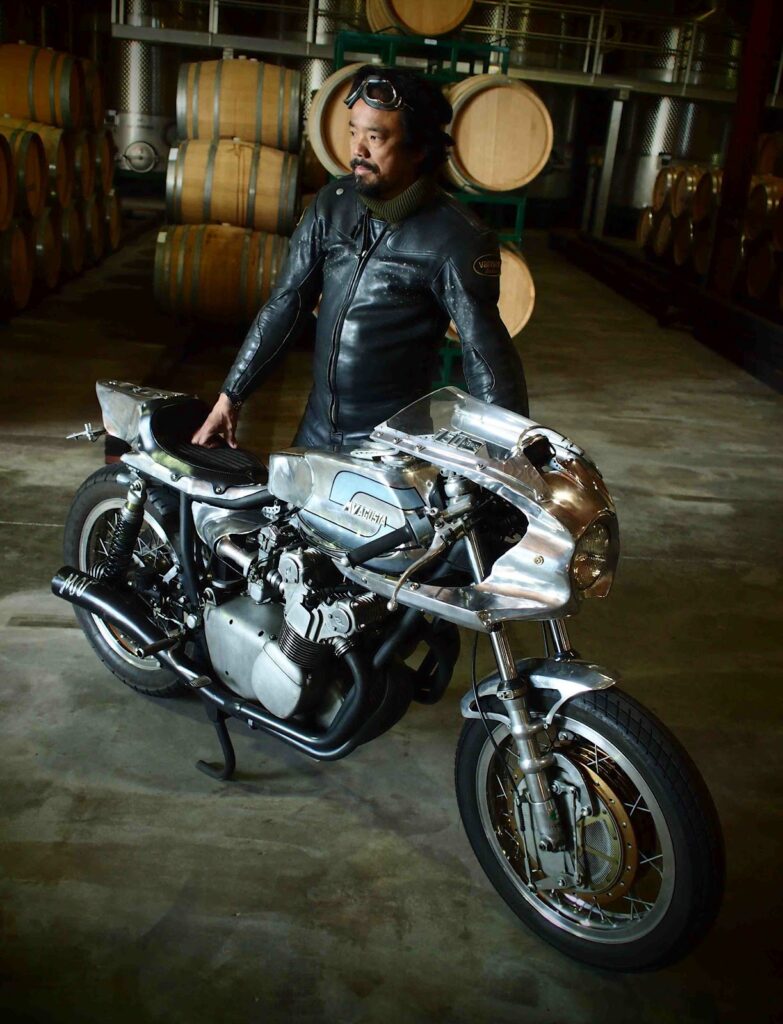

PDO: Sometimes he has deadlines. I know he was under deadline when he did The Yard Built Program with Yamaha.

TT: Well, that’s commission work for companies who have concrete goals. For the collection owners, the private customers, they just wait until the master says it’s done.

PDO: Let’s talk a little bit about your process.

TT: At the beginning, I asked him a lot of questions because I didn’t know much about custom motorcycles, and that created a kind of tension between us. At that moment, I realized that he is not a craftsman, but rather an artist. The craftsman is answering questions and explaining what he does, while continuing to make his stuff, but as an artist, his mindset is dedicated one hundred percent to what he makes. So if there is any kind of interference, he cannot work. He once told me, ‘Can you shut up, because I’m going to throw a wrench at you’. That was how he tested me.

PDO: Well, it speaks to his process. Absolutely. He needed the mental space.

TT: Exactly, and I appreciated that comment because he trusted me somehow; that I could listen to him and find a middle ground so we can better understand each other. He threw his honest, brutal, bold comment to me, but at the same time I was thinking the same thing because his process itself is so beautiful, and moving for me. I didn’t need to ask him questions; what he was doing in front of me was a piece of art, and worth watching. I think the audience for this film will appreciate that. So I stopped asking amateur questions and I just concentrated on filming him. I developed an enormous respect for his work but also for Shinya because he let me film and follow him around.

TT: Right, so after our tense encounter, I tried to erase my existence. I wanted to let Shinya do his stuff as if he’s alone in the space. My camera is just the audience viewpoint; we’re visiting his workshop and observing him from a distance. Little by little, our trust and relationship developed. I did try to be in his sight. There is a scene where he goes upstairs to take a look at the motorcycle from above and I wanted to film his point of view. When I asked him later if that bothered him, he said he didn’t even see me! I really appreciated that, developing a mutual understanding between the artist and filmmaker. It was a gorgeous moment for me.

PDO: If you know Shinya personally, he doesn’t say a lot but he also expresses himself beautifully. He speaks better English than he lets on but he often prefers to let Ayu speak for him. I think he feels freer speaking Japanese. I also think it’s great you captured the art of motorcycling and riding very poetically. And his space itself is a work of art. If you compare it to other motorcycle garages, which are these impeccable, surgically clean spaces, you think, how can you make art in a space like this? You need soil to grow a plant and there’s no soil there. Getting back to your film: how does the Moto Guzzi fit in here?

TT: The choice of Moto Guzzi was perfect because Shinya and I both love Italian design, and particularly industrial design, as he mentioned in the film. Also, this year is the Moto Guzzi centenary, the one hundred year anniversary of the brand. It’s one of the oldest commercially available motorcycles right now. I thought it would be such a beautiful occasion to film the process of this beautiful Italian motorcycle customized by Shinya Kimura.

TT: Shinya can actually talk a lot. After he’s done concentrating on his work, he had his coffee or tea and we talked about a lot of things: our families, how he’d grown up, and he talked a lot about his family in Japan. So I decided to go to Japan to interview them along with another Japanese motorcycle journalist who knows his footsteps before he came to the US, and his seat maker who still works for both Zero and Shinya. But the most important and most interesting part was interviewing his family. His family had a screw making factory that was 150 years old, one of the pioneers of screw making in Japan. Shinya initially told me to see his elder brother, so I went to Hideo’s place and it was such a surprise that all his sisters and his sister-in-law were there too. I ended up filming all of them together as if it was a family reunion. As Japanese, we are very reserved at first, very polite and try not to ask private questions. However, Hideo said you can ask us anything because Shinya gave us carte blanche.

PDO: That’s very trusting.

TT: I have much respect for Shinya and I’m very grateful to his family. Then he showed me the family pictures and shared the memories not only of their parents, but all their grandparents and ancestors.

PDO: What was the most memorable or intriguing story that the family told you about Shinya?

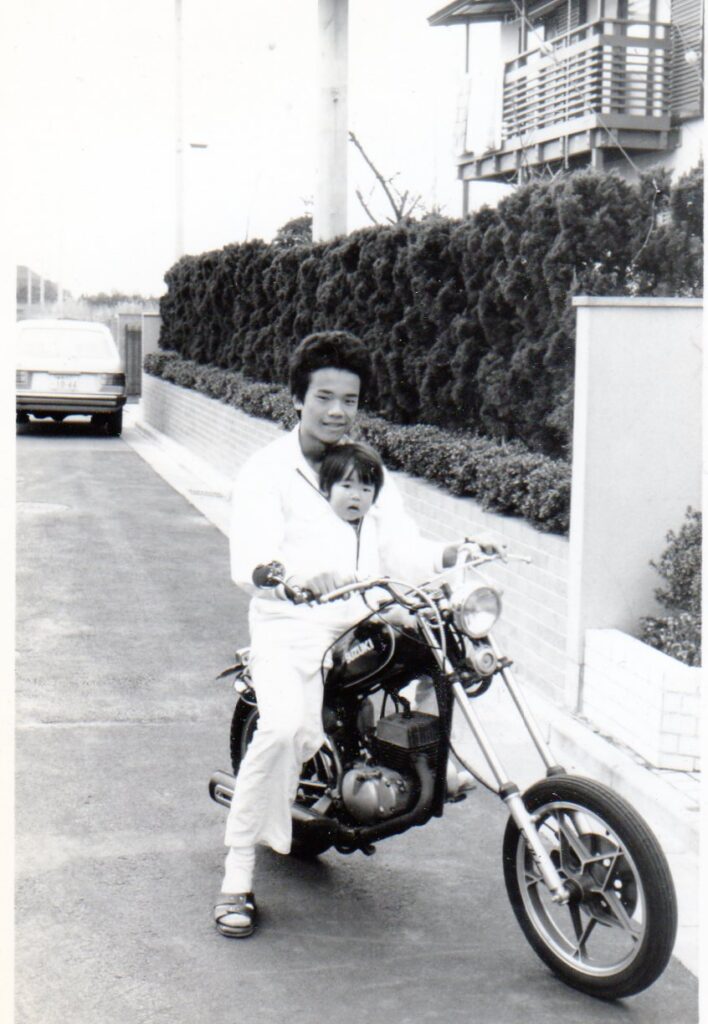

TT: Their grandfather had one of the first Indian motorcycles in Japan, and his father had an early Harley-Davidson. But what touched me the most was the love and affection his siblings had for their little brother. Even though they have lived apart since he was eighteen, when he left to do his studies and start his own career, their hearts and minds are always with him. His brother also keeps a space for him with the family company so he can always come back to the business. That’s a really touching story.

PDO: Can you imagine Shinya running a screw cutting business, what kind of screws would he make?

TT: Artistic, maybe screw figure objects.

PDO: I’ve been lucky to see some of the pictures of Shinya with his first moped, and his first motorcycles. Young Shinya is adorable. I think a lot of Americans, especially Harley enthusiasts, don’t know the history of Harley-Davidson in Japan. It’s actually a complicated history, and we’ve done some articles on The Vintagent about it. Baron Okura was privately importing Harley-Davidsons for sale in the Teens and Twenties, but wasn’t importing any spare parts, and there was no service available. The factory sent Alfred Childs to Japan to set up a proper business in 1926 or so. The Japanese market basically saved Harley-Davidson from going bankrupt in the Depression. Harley Davidson doesn’t like to talk about it, but that sale saved them from bankruptcy. The Japanese Harley-Davidson division licensed the design of the W model, the 750 sidevalve, to produce in Japan, which including buying H-D’s machine tools and a tone of spare parts, all for cash, and it was a huge sum. The Japanese H-D clone was called the Rikuo. When the political situation changed in Japan, they stopped paying licensing fees, and the Rikuo became the principal Japanese military motorcycle, in the late 1930s. That was when the relationship between H-D and Japan became adversarial. Then of course World War II began, so I think that is part of the reason why Harley-Davidson doesn’t talk about its deep relationship with Japan – they were the number two export market after Australia.

TT: When he founded Zero, he actually built his first custom motorcycle. He worked at a motorcycle dealership initially and primarily repaired imported motorcycles. He wanted to try something new, and with the help of some guy he met at a bar, he started Chabot. That was a one man repair shop but then he got the idea that he could do some customization. Before that, he didn’t have any record of customizing anything.

PDO: That’s amazing because the Zero style is so distinctive. They’re very low and long and raked-out. They’re not choppers as Americans think of them, the riding position is completely different than you see on customs here. I’ve been in the south of France – in Toulouse – and seen a Zero. They are everywhere.

PDO: It’s a classic story. He had partners and investors and the demands for a return on investment means production. I don’t think that sat so well with Shinya ultimately. It must have been a huge transition to move to the United States and reinvent himself.

TT: It’s a renaissance, a rebirth of Shinya Kimura.

PDO: The film took three years because that was the arc of the creation of this motorcycle. Was it frustrating that it took so long?

TT: No. Each time I visited his workshop it was my pleasure. I felt fortunate to see the progress because his creations are so beautiful, so intriguing and so human – crafted by his hands. It was also my pleasure to be at the workshop simply as a friend and talk with him not only about motorcycles, but the current news, what’s going on in society, climate change, kids, everything. Baseball too. We talked a lot about Shohei Ohtani.

TT: Shinya introduced me to Ayu in the beginning but while we were filming, she stayed out of the picture, mostly in the office space. I asked her to turn off the radio and music because it’s an editing conflict and also a concern for copyright clearance. I just wanted to hear the sounds of Shinya making stuff. I gave Ayu a bit of a hard time because I made her hibernate in this little corner, but she’s a great person. I really believe she’s pivotal for the rebirth of Shinya Kimura.

PDO: How was she pivotal? Was it Ayu that brought him to the United States?

TT: She was born in Japan and she still has family there, but she grew up in the States. She’s really American Japanese. I don’t know if Ayu brought him here but I think it’s half of the reason he came. I think that if there is no Ayu, there is no Chabott Engineering. Together, they built that workshop from an empty space.

PDO: She’s an unsung part of this story and I think she’s remarkable.

TT: She’s also very reserved and really prefers to be behind the camera, and behind the Shinya Kimura / Chabott Engineering structure. I really wanted to interview her because she’s a necessary part of describing the man behind the image. The interview with Ayu was one of the very last segments of the filming. In total, we filmed 100+ days. We finally got the permission to interview her at the very end of this production cycle. I was relieved she finally trusted me to film her. It was actually more challenging than filming Shinya.

PDO: Shinya likes to talk and Ayu doesn’t as much.

TT: She talks among friends but rarely for the media. It was a very joyful moment to finally have her agree to the interview.

TT: We started as a ‘process’ film but it’s not. We wanted to know who Shinya is and how he lives and works. I finally concluded that at the end of the day, no matter what a great artist and custom motorcycle builder he is, he couldn’t do this alone. Behind the camera, there’s his family, Ayu and friends who more or less supported him – not influencing him artistically, but as a human being and as a man. There’s a lot of deep relationships, particularly with his family and that touches me the most. I threw away the entire first rough cut and I restarted cutting from the intimate family scenes. That became the final work. I hope the audience can appreciate not only the artistry of the master at work but also the deep family emotions and love.

PDO: Your film is unique for about just any artist in including his family! I can guarantee you a documentary about Jesse James or about Willem de Kooning would not include interviews with their family. It’s a rare approach, instead of the ‘solitary genius’ narrative that’s so cliché in our culture. People don’t emerge from nothing. People actually require a tremendous amount of support to create something new and innovative. Nobody works in a vacuum. There’s history, there’s research and there’s education, there’s the support you have and require just as a human being. It’s quite a beautiful film, and not what one thinks of a ‘motorcycle film’ or a ‘customizing film’. It’s a film about an artist because of the way Shinya speaks. It’s the emotions around motorcycle design, and very successful in that sense.

TT: And his family is not passively supporting him, but is just there to show their unconditional love. That’s what’s so moving and beautiful. It’s my responsibility now share this film with a wider audience, not only the niche, hardcore motorcycle or custom scene fans. I want the audience to see that here is a great artist, but above all, here’s a great human being with his family and friends around him. I really want to share this film and that perspective with a wider audience.

TT: What I’ve learned in documentary filmmaking is that you must put your camera in the right position. With my crew, we would bother Shinya going into his private, intimate creative space. The same with lighting – if we set up light or even a reflector, we would be invading his space. The key was to work with the available lights and position the camera in the right place. I learned that from the high profile director of photography, Darius Khondji.

He’s done a lot of big feature films and he said that no matter what kind of lighting you have, the key and the most important thing is to put your camera in the right position.

NA: At some point in the film, Shinya says that building a motorcycle is 10 to 20% being an artist and 80 to 90% being a mechanic. The world sees him as this great artist and his motorcycles are definitely works of art. Do you think he sees it that way?

TT: I think he sees the motorcycle as a machine first. As Paul said, it’s a work of art, but it runs and you can ride it. I think if you called him an artist, he’d appreciate it. He’s a very open-minded and versatile person. So if somebody called him an artist, I think he’d say, okay, maybe I’m an artist or if somebody called him a perfectionist and can restore any kind of vintage motorcycles, then he’s okay with being a mechanic. He’s just him.

TT: It’s very reserved, very sane but also so powerful and deep.

NA: Thank you for making the documentary. It was beautiful.

TT: Thank you for watching it.

More articles on Shinya Kimura over the years on The Vintagent:

- 2006 Legends of the Motorcycle

- Shinya Kimura: ‘I Am A Coachbuilder’ (2011)

- Test Ride of Shinya Kimura’s MV Agusta 750 Sport (2017)

- ‘Faster Sons’ Yamaha Yard-Built program with Shinya Kimura (2017)

- Needle and Sleeper in Custom Revolution (2018)

- El Mirage by Wet Plate (2017)

- Cafe Racers Invade Sturgis (2012)

Shinya ! I’ve said it before a million times and goramit I’s gonna say it again .

Shinya has influence more custom M/C custom builders … most who are loath to admit it ( including the likes of Hazan etc ) than any other builder of the late 20th and 21st century ,

I’ll always remember showing Hot Rod legend ( and friend ) Neal East Shinya’s ” Zero Chop Spirit ” book … watching Neals jaw drop as he identified many of the bits and bobs on the bikes … literals blowing Neals mind .

And one of my favorite moments was having Shinya feature my music on one of his videos … an honor indeed .. and the ,setting of two Senies

Gotta just love some servers spellcheck . Case in point . Type in SENSEI …. retype it five times because the goram spell check keeps insisting on changing it ….. finally get it to stick … and what shows up regardless of your efforts ?

See above … along with the words coming together ‘ spellchecked to read ,setting

BTW .. wtf is a senie ?

I give up ! Let the digital weenies rule the roost …long live analogue ! As well as genuine craftsmen like Shinya