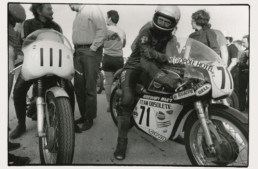

When I decided to ride in this year’s Motogiro d’Italia I thought I had a pretty good idea of what to expect. I had been doing related research and had written an article on the history of the event for The Vintagent. However, I had never participated in any kind of motorcycle competition before and quickly had my vision of what a road “race” means transformed.

looks a fantastic event ,, but the event website doesnt mention the cost ,,suspect its in the if you have to ask its too much range