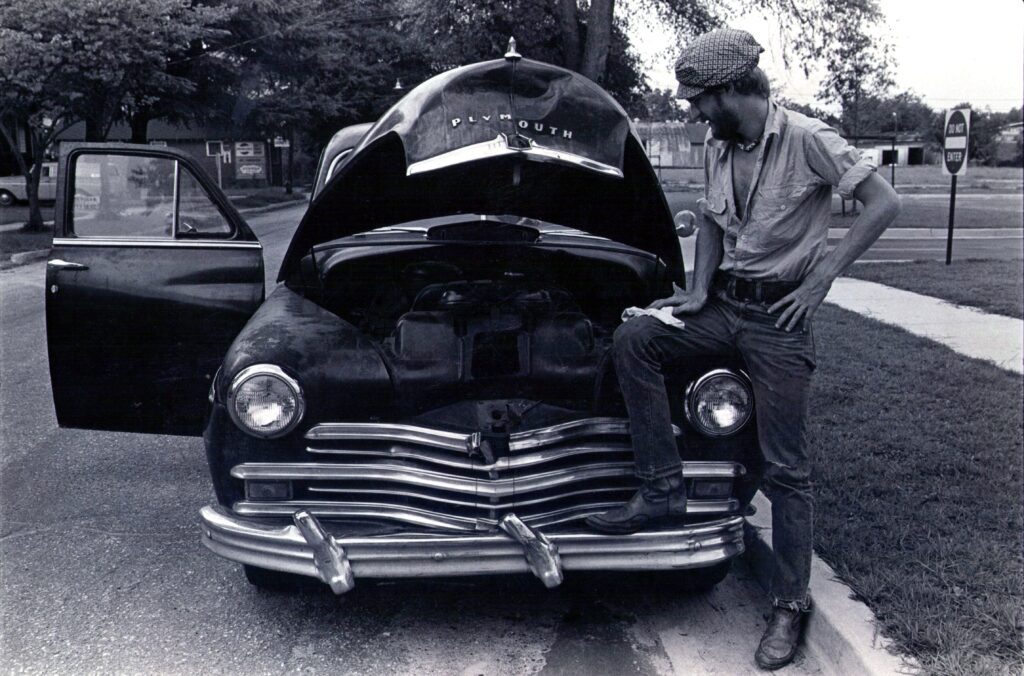

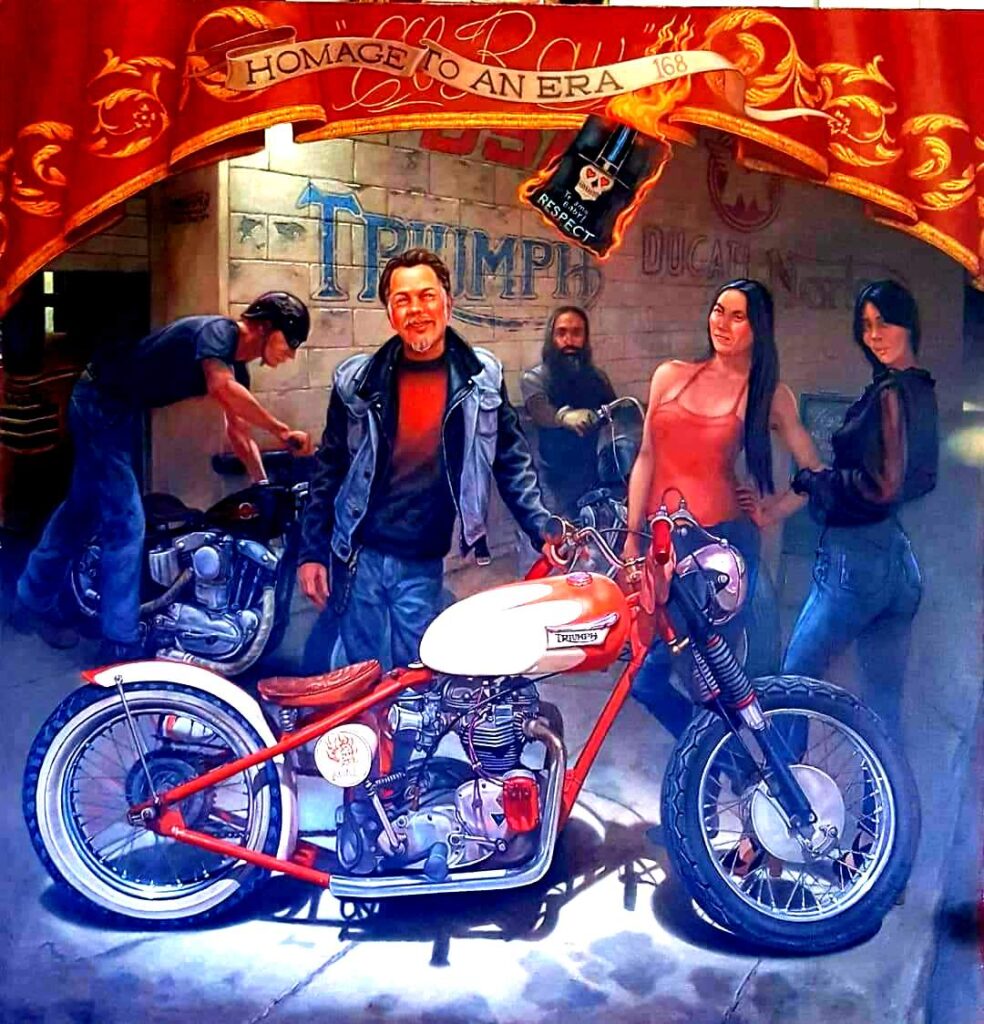

Remembering Ray Abeyta

An Aesthetic Thing

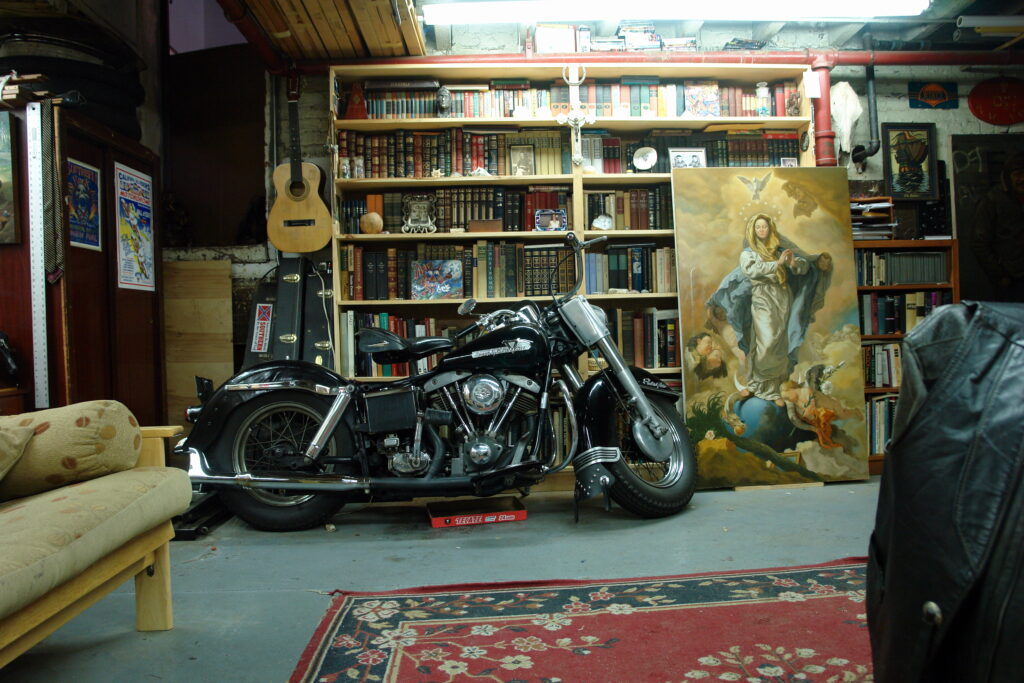

Today a lot of this history has been reduced to a “look” but one of the things I like about my motorcycle is that it predates all the bullshit. It’s nuanced and subconscious, but when I made it I was really just thinking about building a bike that runs. Something I could use to get out there on the New York streets that runs mechanically and safely and is in tip-top shape. Particularly if I was going to ride the hell out of it – and that’s how I like to ride. Riding in New York is an intense thing, and I like the intensity of it. Jamming the bike, splitting lanes; it’s exciting. The adrenaline pumps. It gets hairy. So many close calls. The look of early outlaw bikes was a statement. These guys were exploring how to make things look fast. They might not have been able to put it into words but this is why they were doing it.”

On the Unspoken Nature of Motorcycling

“These guy’s bikes looked like they were going fast even when they were standing still. They looked like they are going to blast-off. Like when you look at an old photograph of a race car driving around a track; all the cars are pitched forward. So these San Francisco outlaw stance bikes were exploring this same perception of velocity. They might not have been able to talk about it but that’s what they were doing: blood knowledge and muscle memory. These guys were riders and they were building fast bikes, they knew what it felt like when they hit it. So they were building a bike to look like that. They had an internal knowledge of what the machine should look like. So were these guys in San Francisco thinking this way about how they were making their motorcycles? Maybe; but maybe not. They just made them like they wanted. I just made my bike like I wanted. But the stance and the look of these bikes had come from someplace. Nobody could even talk about it but their machines just affected people in deep ways.”

East Coast vs. West Coast

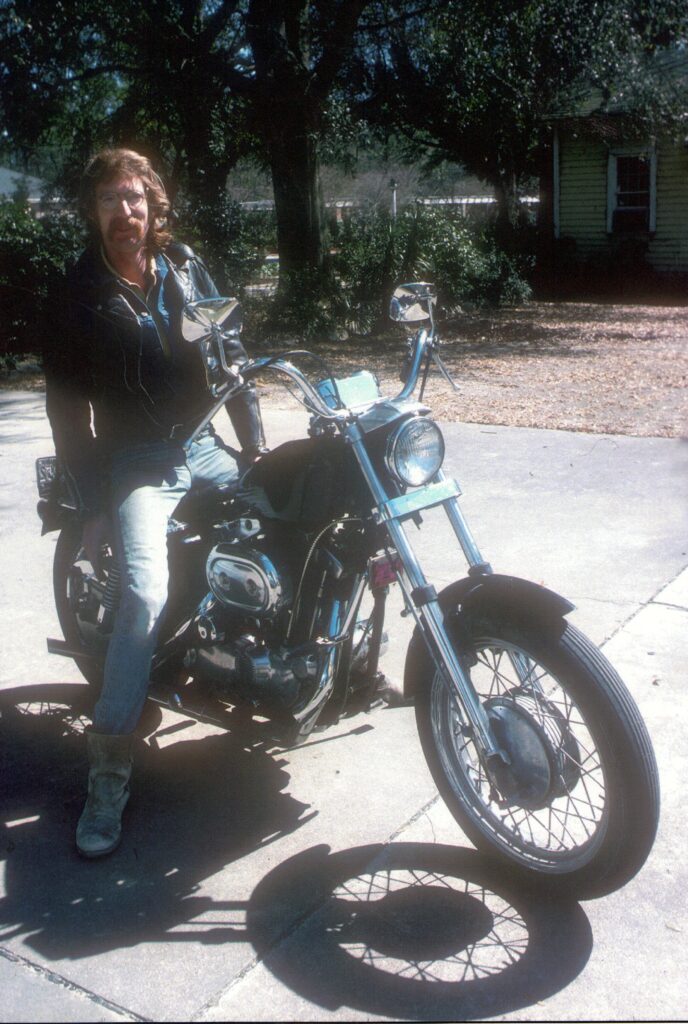

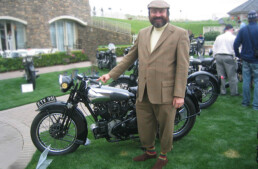

People will talk about East Coast/West Coast styles and I think a lot of the East Coast style is from New York City. Narrow bikes that you can cut through traffic with. But that style also goes back to the California outlaws and their bikes. ‘Frisco style tanks. The Sportster tank was the prototype for that style. There is no motorcycle tank that comes close to it. Two and a quarter gallons of gas. I can run for about an hour and then I need more gas. You can change the tank a bit; raise the cap and add a petcock so you get about a half-gallon more gas. Guys in San Francisco invented that style tank. That’s an aesthetic I like. I finished building this bike about five years ago. It took me more than four months to build it. My friend Billy Phelps the photographer was working on something for Harley. He called up Ray and me and asked us to meet him over on Front Street in Brooklyn. He did a photo shoot set up with us and our old bikes and sent it to Harley. So, Harley went for his idea and then he set up a big shoot for the advertisement. There was a tractor-trailer full of new Harleys that he used in the shoot. The representative was there from Harley overseeing the shoot – my bike was parked there and the representative looked at it and said, “Ah, there’s that bike – whose bike is this?” The rep said that he had showed a photo of my bike to the president of Harley and the president said, “This is what a Sportster should look like. This is it.”

I Am a Southerner

I am a southerner; I love to ride down south, that’s where I grew up riding. Country roads with smooth surfaces. It’s relaxing. I am very aware of my connection to a region. And from that I have an understanding of other regions in America – Southwestern, Appalachian culture. As a kid I hitch-hiked all around the country. I am acutely aware how in America there are these great epic stories: Huckleberry Finn, Moby Dick, John Steinbeck, and the Civil War. I am aware of this and I try to explore this narrative approach with my painting. My painting style and how I like to paint has a lot to do with craft and a sense of tradition. My Sportster also has a lot to do with a sense of craft and tradition. I’ve been drawing and painting for a long time. I’ve been making pictures with people in them since I was nine years old. Now I see a lot of this kind of thing disappearing. I have done all these paintings of people and places in New York and it dawned on me sometime during the process that I was painting things that were disappearing. Works Engineering, where I had my studio, was an important place, there were some creative people there. It was a golden time.

Glad to see there at least a few remaining revenants of the greater NYC I lived in ( 70’s) despite the rampant gentrification ripping the soul out of the place bit by bit .

Damn … I know I was young ( 20’s ) stupid and thought I was invincible … but I miss the days of waking up in Hells’ Kitchen ( later a REAL loft in the garment district ) patting myself for surviving yet another day in NYC

FYI ;

Re; East Coast vs West Coast style

Having lived on both coasts … NJ NY VT WA … CA WA as well as Vancouver BC ( CDN )

The East Coast HAS style … whereas the West Coast follows what ever Trends come their way

Of coarse that is a generalization as there are always exceptions to the rule . But overall .. from M/C’s- to Fashion – to Music – to Literature ( especially literature ) …

…..the East is the Beast … whereas the West follows the rest like lemmings over a cliff .

😎

Though less true in this idiotic age of social media and security concerns … a comedian who’s name escapes me at the moment perfectly described the difference between living in NYC and LA ;

” In NYC you can find yourself riding the subway alongside $$$$$$$ captains of industry and finance .. Whereas in LA you’ll find yourself driving alongside a pimped out Rolls Royce driven by someone on Food Stamps ”

e.g. On the west coast its all about image image image … reality and debt be damned