Elsie Knocker was born Elizabeth Shapter (July 29 1884 – Apr 26 1978) in Exeter, was orphaned by age 6 (her mother died when she was 4, her father at 6, from tuberculosis), and adopted by Emily and Lewis Upcott, a teacher at Marlborough College. The Upcotts had the means to send Elsie to study at Chatéau Lutry in Switzerland, and she later trained as a nurse at the Children’s Hip Hospital in Sevenoaks. She married Leslie Duke Knocker in 1906, and they had a son, Kenneth, but divorced soon after. She then earned her living as a midwife, and to save face during Victorian social strictures, invented the story that she was widowed when her husband died in Java.

She became a passionate motorcyclist, and wore very stylish outfits while riding, notably a dark green leather skirt and long leather coat, which was cinched at the waist to “keep it all together” – the outfit was designed by Alfred Dunhill Ltd! She owned various motorcycles, including a Scott two-stroke, a Douglas flat twin, and a Chater-Lea with sidecar, which she took to Belgium during the War. She earned the nickname ‘Gypsy’ as a member of the Gypsy Motorcycle Club, and because she loved the open road.

Chisholm and Elsie Knocker had to apply for Dr Munro’s Flying Ambulance Corps, and beat out 200 other applicants. Knocker was a natural, both as a nurse, and because she was an excellent mechanic (and driver), and spoke both German and French fluently, from her Swiss schooling. Lady Dorothie Fielding and May Sinclair were also included in Munro’s special unit, with all women acting as nurse/ambulance drivers, and they all landed at Ostend in September 1914. The team initially set up camp at Ghent, but by October they’d moved to Furnesin, near Dunkirk, ferrying wounded soldiers to the hospital who’d been carried from the Front. They soon realized they’d save a lot more lives if they were actually at the Front, regardless the horrors they’d already witnessed. “No one can understand, unless one has seen the rows of dead men laid out. One sees men with their jaws blown off, arms and legs mutilated” – Chisholm.

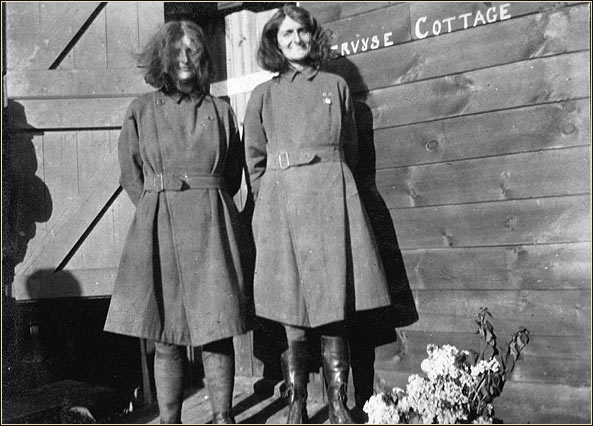

This was their life for an incredible 3 1/2 years; treating the wounded as totally free agents, who had to raise their own funds at first. Luckily, they had a camera, and began photographing the front, which secured them space in British newspapers, and the fame of these women motorcyclists began to grow, and funds to flow. When they needed a bullet-proof door for their clinic, it was supplied by Harrod’s! They returned occasionally to London on fundraising tours, riding a sidecar outfit and collecting money, knitted socks and hats for the soldiers, as well as tobacco and cigarettes. The press loved them; ‘Sandbags Instead of Handbags!’ proclaimed one British paper.

Their proximity to a local Belgian garrison eventually gained them an official attachment to the Belgian military. Word of their bravery and their work saving soldiers under incredibly difficult conditions spread far and wide. Fellow Flying Ambulance Corps member May Sinclair described Knocker as “having an irresistible inclination towards the greatest possible danger.” Many times the women crossed the front lines to save fallen soldiers, sometimes carrying them on their backs through the mud, and under fire, including one German pilot who’d been shot down and wounded in No Man’s Land. For that, they were awarded the British Military Medal and were made Officers of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, and awarded the Order of Léopold II, Knights Cross. Yet more awards and honors followed, including the Croix de Guerre, which meant the ladies had to be saluted by all the soldiers, which they found most amusing.

After the War, the Belgian Baron discovered that his wife Elsie Knocker was not a widow, but a divorcée, and the Catholic church forced an annulment of their marriage. Read into it what you will, but apparently that was the breaking point of her friendship with Mairi Chisholm. Chisholm took up auto racing after the War, but her injuries (from the gas attack and septicaemia) had weakened her heart, and doctor advised her to take it easy. She spent the rest of her days on the estate of her childhood friend May Davidson, and moved with her to Jersey in the 1930s, and never married (a man). Elsie Knocker was a senior officer in the WAAF during WW2, and earned distinction, but lost her son in the RAF in 1942, and left the military to care for her elderly foster-father. She lived the rest of her life in Ashtead, Surrey, and was notorious for being “flamboyantly dressed with large earrings and a voluminous dark coat!”

Good story on the “Angels.” Sometimes I think we never will fully understand the people who fought that war.

What a story! The British press picked up the women’s story in the past few years (after Dr Atkinson’s new biography), which is played mostly as a ‘why do we suck today?’ feature. There’s a curious coincidence of oppression and tremendous achievement – these women couldn’t vote, had limited property rights, and limited prospects as Victorians, yet far exceeded anyone else – male or female – in bravery and hard work. I can’t think of anyone who spent 3.5 years at the front!? Simply amazing.

Excellent and timely story ( what with the 100th anniversary of the end of WWI ) .. but in need of a minor correction . You have Chisholm’s BD as 1986 when it should read 1896

Also a suggestion ? Might I heartily recommend you forward this story ( and any references etc ) to the curator / staff of the KCMO WWI museum .. which is the best and most comprehensive museum dedicated to the War to End All Wars in the US .

Because honestly … they need to feature these two women .

FYI ; Quite a few soldiers from both sides remained on the front thru out the entire war .

Great article – it’s ‘Pervyse’ though (see the magazine front, and the photo of the outside the hut). Nowhere in Belgium called ‘Peyvres’ as far as I know. The Dunhill riding outfit must have been a sensation at the time!

Thanks Nick – I’m a little dyslexic in my dotage…

More here http://myroyalenfields.blogspot.com/2010/08/elsie-and-mairi.html

Great read! There were a lot of brave ladies in that war. I have been reading the Maisie Dobbs novels lately. Jacqueline Winspear the author brings a lot of these unsung heroes to light. Thanks

What a great read, thank you.

Great account of two formidable ladies…I’ve also been reading about Gertrude Bell…friend and colleague of Lawrence of Arabia and Churchill . Not sure if she was as fond of a Brough as Lawrence….Steve

Frankly, I guess such articles must be published more

and more due to the current circumstance and modern needs of the Millenials.

I read them to find some fresh information that will correspond to your own requirements.