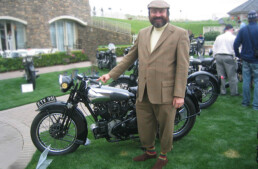

Had a Playboy magazine editor accepted one of Peter Egan’s stories, we might never have enjoyed his outstanding talents as an automotive and motorcycle journalist. While working as a foreign car mechanic in the 1970s, Peter wrote two novels and several creative short stories in his off-hours. But, as he explained during a recent telephone interview from his home in rural Wisconsin, he was instead sent endless rejection slips. “I’d send the short stories into serious magazines,” Peter explains, and laughs and continues, “Playboy, and so on. But lo and behold, you know, they’d rather have Norman Mailer than Peter Egan on their pages.” The world might also not have been treated to Peter’s latest project, Landings in America: Two People, One Summer and a Piper Cub. Published by Octane Press and set for release on August 12, the hardcover book is an insightful memoir/travelogue told in Peter’s distinctive writing style, recounting a flying expedition he and his wife Barbara undertook in 1987.

With his love for airplanes, he also took flying lessons during high school. He passed the ground school training but only had an hour or two of actual flight time under his belt, before his dad made him quit; he was spending money on the lessons and not saving for college. “But to me, it’s all the same,” he says of airplanes, cars and motorcycles. “Adventure with vehicles and places you can go and things you can do.” When he was writing for the magazines, he often enjoyed finding a car or a motorcycle that “had the same spirit as the trip I was taking,” he says. For example, a 1963 Cadillac that he drove to the Mississippi Delta to visit the home of blues music. “A real blues mobile,” he says of the land yacht.

Peter Egan … this side o’ the pond’s answer to LJK Setright ( though LJK did have a bit of an edge what with his Latin and Audiophile knowledge )

But ole Peter .. as down to earth as you can get .. a wealth of knowledge when it came to M/C’s autos and aero … and a damn fine writer to boot .. loved every word he’s written … looked forward back in the day every month to his latest in CW and R&T .. bought al his books as I will this one … took his advice more than once .. loved his commentary on the blues ( albeit somewhat inaccurate ) as well …

Ahhh … Peter E …

So kudos to Peter for yet anther new offering .. and to you Mr Williams for cluing us all in . .. nicely done profile I might add !

Yay … another Egan book to read and add to the shelves … yay .. a good way to end a pretty damn .. err .. hmm .. lets call it … chaotic week in the world and our ” Broken Promise Land ” ( Ry Cooder – ” Borderline ” )

😎

Damn .. did it again .. screwed up the email address by one digit … caught it just as it loaded .. triggering the ole digital cops once again … mea culpa … )-:

Peter Egan … this side o’ the pond’s answer to LJK Setright ( though LJK did have a bit of an edge what with his Latin and Audiophile knowledge )

But ole Peter .. as down to earth as you can get .. a wealth of knowledge when it came to M/C’s autos and aero … and a damn fine writer to boot .. loved every word he’s written … looked forward back in the day every month to his latest in CW and R&T .. bought al his books as I will this one … took his advice more than once .. loved his commentary on the blues ( albeit somewhat inaccurate ) as well …

Ahhh … Peter E …

So kudos to Peter for yet anther new offering .. and to you Mr Williams for cluing us all in . .. nicely done profile I might add !

Yay … another Egan book to read and add to the shelves … yay .. a good way to end a pretty damn .. err .. hmm .. lets call it … chaotic week in the world and our ” Broken Promise Land ” ( Ry Cooder – ” Borderline ” )

😎

Is he the guy in Cycle World whose monthly articles were always accompanied by those neat watercolors of classic bikes?

Same!

Not to mention Road&Track as well as a few others on the side . Suffice it to say .. over here … for any reasonably serious GearHead .. be it M/C’s 4 wheels or Guitars .. ole Peter was a constant presence and a cultural force to be reckoned with .

I’ll read anything Peter writes! His was always the first column I read in every Cycle World. I’ve felt a kinship with him for many years. I fell for old British bikes(4), bevel and belt-drive Ducatis (8) and been flying for over 45 years. Just can’t get the blues guitar down……

If yer ever out here Denver way … look me up .. PdO knows how to contact me … guaranteed a weeks worth of lessons and I’l have you well on your way … FYI ; teaching was a major part of my career in music .. from private to conservatory .. and teaching serious hobbyists … has always been a joy

Suffice it to say there’s nuthin more fun than being a bad@$$ed guitarist who can both play and teach ( cause I’ve never forgotten what it takes to learn ) and watching the smiles on students faces when they finally … get it !

And the blues .. well Ted ole bean .. lets just say there’s a reason I owe Black America a massive debt beyond repayment .