By Kevin Day

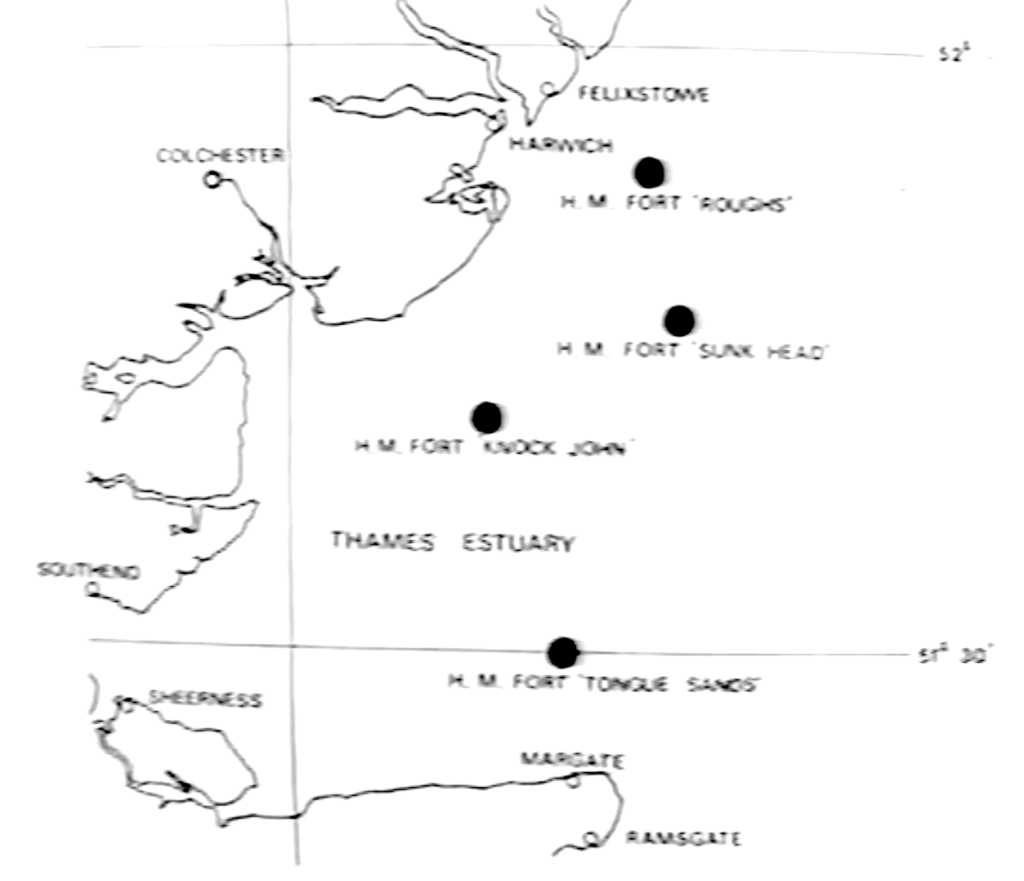

My friend Kevin treated me to a trip out into the seaward end of the Thames estuary to see the WW2 forts. To get there, we traveled down to Kent, then crossed the bridge to the Isle of Sheppey, which is reminiscent of Orwell Bridge on our home turf. Once on Sheppey we soon found Queensferry dock and parked up. There were lots of screaming kids and their parents at the jetty. Surely, we aren’t going to be seven hours at sea with those little horrors? But luckily enough they are just waiting for the Jet Ferry to Southend, off for shopping or McDonalds or roller-skating or whatever you can do in Southend to please the kids on a Saturday morning. After all they’ve all gone our boat’s owner, Martin Hurley arrives and gives us a brief briefing and I’m sure that he said the captain was his husband, but Martin doesn’t accompany us on this voyage. The captain is old – Captain Alan is his name – and the first mate leans over to talk to us; he’s a chunk of a man, a London/Essex type, although later he claims to be from Devon.

Completely off topic … utterly fascinating !

And ahh … Pirate Radio …. the roots of R&R in England back when the BBC banned every bit of it .. xenophobic arseholes that they were !

Radio Caroline was the main one . Lord Sutch ? Much better know for his musical exploits .. political shenanigans and all around hell raising … but yeah .. he did the radio thing for a bit as well …

So in conclusion … Nice One PdO .. a complete shocker in light of the off topic subject … but hey .. what the hell … a lil off topic now and then’s a good thing … a very good thing indeed

LFWOCZR !

😎

And now a word from our sponsors .. oh wait .. this site hasn’t been enshitified yet … we aint got any … and thats a very very good thing !

There was an episode of Secret Agent Man where he had to go out and deal with some young groovies who were operating a radio station on one of those gun mounts in the english channel.Maybe they were really russian agents posing as young groovies,cant remember.

” Secret Agent Man ” … two thumbs up .. Patrick McGoohan’s precursor to what would become his absolute masterpiece .

Though yer use of ‘ groovies ‘ pretty much reveals who and what you think you are . But back to …

” The Prisoner ” … psychology … brain washing … philosophy … etc … brilliant to the point of genius .. and the introduction to a young mind ( mine .. yeah .. I was an intellectual nerd back in the day ) to the depths and BS governments etc will go in order to control and get their way … even when you want to leave .

” I am not a Number … I am a free man ” … and his character was … despite the multitudes from drugs to mind control of tactics to make him otherwise . ….. which is what set me on a path of resistance and when needed .. defiance .. not to mention no fear of ‘ leaders ‘ .. from my youth to my present Boomer self .

And yeah … got em all on DVD … watch the full series at least once every couple of years … cause the reality was … every tactic used in that series came straight out of Mao’s book of propaganda …. psychology … DDR interrogation tactics … . military use of mind control etc … documented … not speculated … cause ahhh … ole PM was a perfectionist to the max

IMNTNBR

LWOCZR

cause….. ” I aim to misbehave ”

Go Team Human !

😎

I was hoping maybe someone out there could tell me what episode of secret agent that was and the plot.