Goodwood Revival 2025

Located in Chichester, Sussex, the Goodwood estate home of the Duke of Richmond turns back the clock each year to honor Britain's glorious mechanical history. The Goodwood Revival first started in 1998 when Charles March (then merely the Earl of March) declared that racing would return to the historic Goodwood Motor Circuit for the first time since 1966. Back then, with racing speeds increasing the family was faced with a choice to modernize the circuit or discontinue racing: the latter was chosen, and things got very quiet for the next 30-odd years on the grand estate near Brighton. Nostalgia is a funny thing though, tugging at our emotions in times of turmoil and change...the simplicity of the past, at least as seen through memory, can provide both comfort and clarity to appreciate our ancestors’ achievements and maybe, even our own youthful indiscretions. When faced with relentless technological change and political turmoil, a little indulgence in nostalgic fantasy is very satisfying, especially when done in the manner of the Goodwood Revival.

Erik Buell: American Innovator

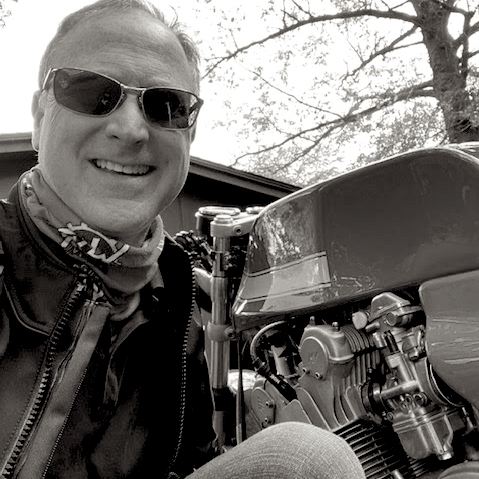

Erik Buell's name is firmly etched in motorcycle history as the visionary founder of the eponymous Buell Motorcycle Company. Buell has long been celebrated as an innovator who challenged industry norms and basically invented the American sportbike, using Harley-Davidson motors in chassis of his own design. The technological trinity guiding his radical chassis designs include perfect mass centralization, frame rigidity, and minimized unsprung weight. His groundbreaking designs include the fuel-in-frame chassis, a rim-mounted front disc brake, and the underslung exhaust systems on his motorcycles. From the founding of Buell Motorcycles in 1983 until Harley-Davidson pulled the plug in 2009, over 137,000 Buell motorcycles were manufactured. After that, Erick Buell switched to designing electric bicycles and motorcycles with Fuell [see our previoius interview here]. Buell motorcycles are still being produced, but Erik is no longer affiliated with the company bearing his name.

John Lawless (JL) Erik, we had to push back our chat tonight because you had a practice session with your band. Is this your touring band for the new album?

Erik Buell (Erik) No, I’m playing bass with friends who cover everything from the 1960s to current stuff. I love playing bass just for grins and we’ve got a very good drummer who won’t let you drift off; he's like using a metronome. It keeps your chops up.

JL I have to say I’m really enjoying your new album Ride Free as well as last year’s Dust Settles. It’s much more accessible than your first album. I hope you don’t mind me saying, but that first album reminded me of your motorcycles, a full-frontal assault of rock-n-roll and horsepower. This one seems to be a more contemplative and personal album with incredible musicianship.

Erik Yeah, that was my metal album Anthem with the Thunderbolts in 2010. We did a lot of shows and then during COVID it really hit me that I was feeling isolated and I missed people. I love engineering but I was kind of fried on it, and you know, one of the best things about Buell (motorcycles) was the people, the motorcyclists I’d met. I wanted to communicate with people again, and I can be creative, so thought maybe I’d writing a little bit of music. All of a sudden my buddy Ralph said “shoot, your writing is pretty good” and off we went.

JL There’s nothing like the immediate feedback you get performing in front of a live audience.

Erik Yeah, I mean I think that’s true and you know it something that’s funny. I’ll tell you a story because you like Ride Free. I was thinking, who are the listeners? Ride Free came from thinking about, you know, being young and wild and when I met my wife, we’ve been together 25 years now. We were together in college and she left me over racing. At that time my heart was broken, but on the other hand I couldn't leave racing. I wasn’t sure if a lot of people would understand what 'high side' means, so I wrote words that related to horses instead, thinking it captured what it meant to be young and wild. You’re going to have to grow up someday but not too soon.

JL I was impressed that you were still able to tap back into that emotion and put that to music. It’s fresh and interesting and it adds another dimension to people’s image of Erik Buell.

Erik I’m just going to say that I do love music and making people happy. This makes me happy, too. I’m still here so the music’s a little bit of the same thing, that if you can reach a few people and I keep myself from being sad and bored, it works.

JL So you recorded Dust Settles in California, how’d you end up in Nashville for the latest album Ride Free?

Erik Another friend of mine, Dave Northrup (studio and touring drummer), called and said they had a cancellation for a day and a half and we went in and did it. Somehow, we recorded the whole album in one day with the most incredible top level musicians in Nashville. Their playing is another world. I didn’t play anything on this one so I could focus on the singing. We’ve been getting airplay on Americana radio for a few months now.

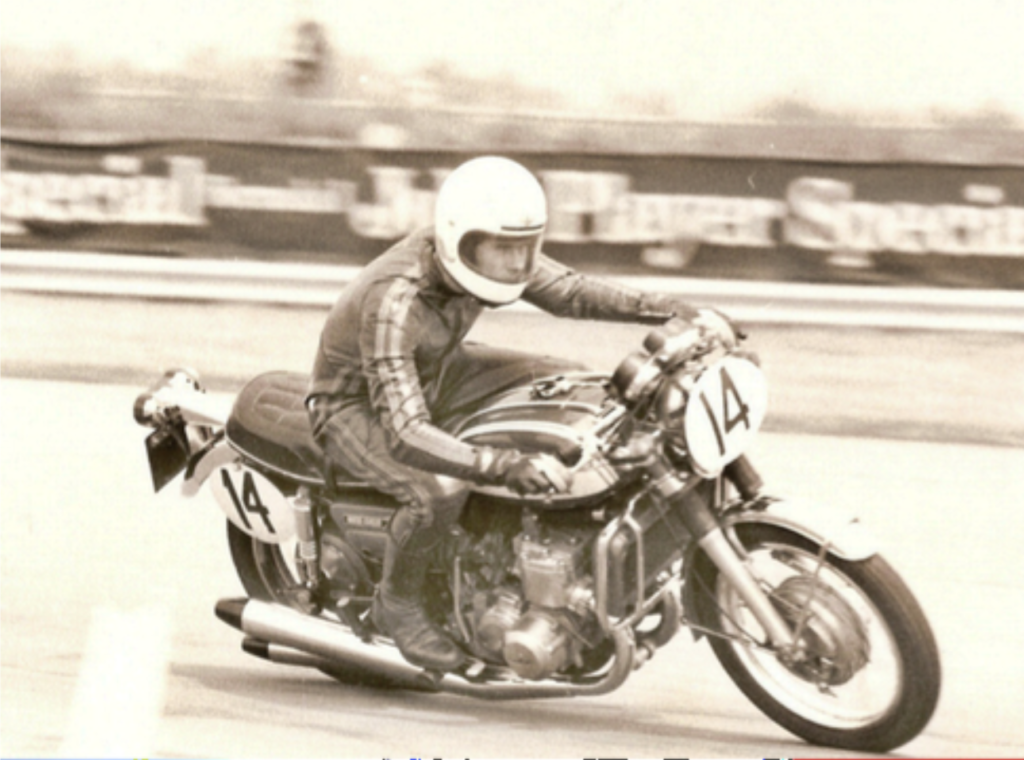

JL So I’ve heard the title song for Ride Free and saw in the video that it references your time racing a Ducati 900SS and Yamaha TZ750. You were doing music in high school and college before you got into motorcycles when you live in Pennsylvania.

JL I think your instincts proved right about that.

Erik I'd have to say that's true! I went back to night school and took a whole lot of courses in the last year before I went to work for Harley-Davidson. It was the lowest paying job offer I got but I went to work on July 1, 1979.

JL So you were there in the AMF (American Machine and Foundry owned Harley-Davidson from 1969-1981) days. You left Pittsburgh and went to Wisconsin to find fame and fortune with Harley.

Erik I just wanted to use my engineering skills and see how it all worked. There were a whole lot of cool people there and Harley was in deep financial trouble so it felt like it really mattered. They had a lot of issues with the old AMF motors. They were horrible and the first job I had in the office was to sort out why. My everyday street bike was a Suzuki GT750, the “water buffalo”, which I just loved. It was so smooth, and fast enough you could really humiliate some amateurs on the backroads. It was a two-stroke with an oil injection system. My GT750 got like 1200 miles to a quart: Harleys were getting just 300 miles to the quart!

After that I started doing dynamic vehicle testing with this old style motorhome with a strip recorder. We’d start recording and we had 14 channel telemetry that would send signals back. The front end was weaving and wobbling its way down the straight. They were really horrible. I started to add more instrumentation and measuring things for the FXR and XR. I wound up putting LVDT’s (Linear Displacement Transducers) that would measure motion so I them on both sides of the fork tubes and then I had them on both of the shock absorbers. Next, I rigged a plate to the swingarm to measure the lateral deflection of the swingarm. As well as measuring steering angle we had strain transducers on the handlebars to see if you were actually fighting it. We started going to the test tracks and I’d have guys - the mechanics and tech union guys that could weld - cobble things together, like making the swingarm stiffer this way or that. We wound up making the FXR the best handling Harley by far. I mean it was really rewarding because it had been the worst. I’d ridden a lot of stuff like the Ducati and TZ750’s and I knew from a rider’s perspective what I liked and didn’t. I was instrumenting Harleys even though they were much slower and bigger because the same things mattered on both.

JL That’s funny, Alan Cathcart recently sent me some photos of him on a Buell RR1000 being pulled over by the Maryland State Police which was staged for the first test ride article of the bike. I imagine you’d had your share of run-ins with the law when you were on your own.

JL I didn’t know you were involved with the V-Road?

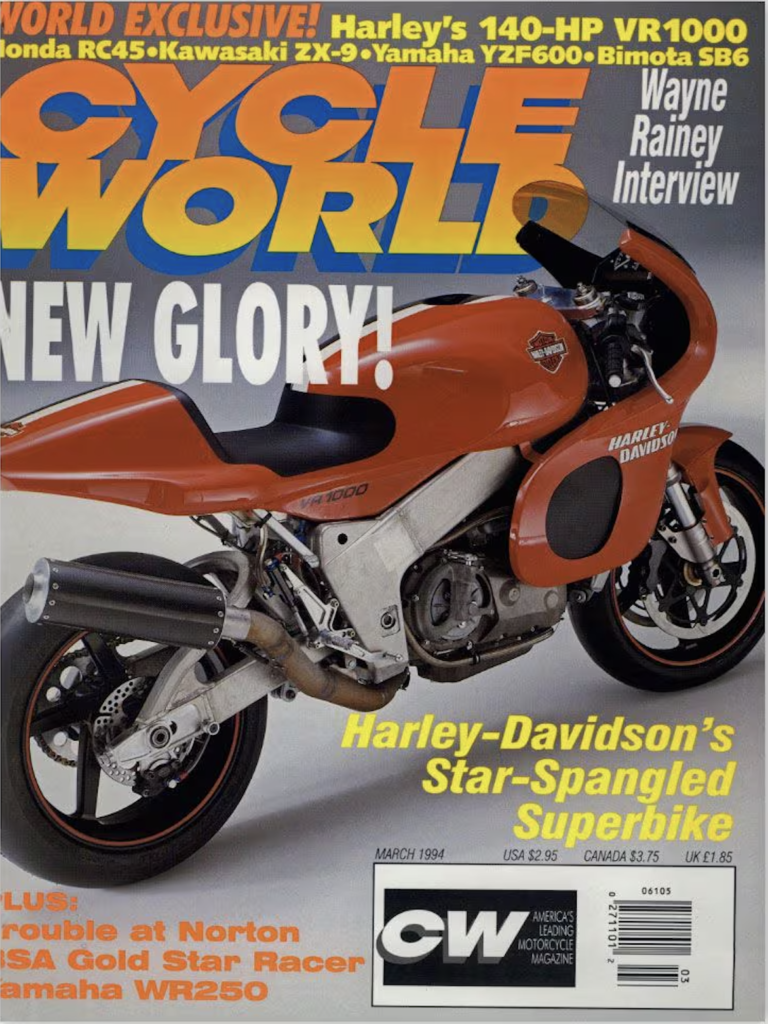

Erik Yeah, it’s a long story, I was involved with the original V-Rod and VR1000 racer but was aced out of them. I actually gave it the name VR early in the design phase, and laid out the engine; a ghost outline of the engine using information from the Cosworth BDG cylinder heads. That basic engine design was a pure outside sketch, I’m not claiming that I built it, or anything, but the outside...came from me, and that was the first chassis. I needed an outside shape of an engine concept to integrate into a chassis! And I was talking to the guys at Cosworth because they were building really high performance motors.

JL Was there more to it?

Erik, Okay, I’ll tell you about the hardship. So I had been working at Harley, and left to start building by Buell motorcycles. A little way into that they asked me to consult, because they were thinking about building a road racer and head seen me built the RR1000. They wanted to go AMA Superbike racing, this was probably in 1986. Yeah, we went into a meeting and they said they were thinking of taking the XR750 engine and pushing it out to 1,000cc and put a 5-speed in it, because the XR it had a 4-speed gearbox, and they wanted my help on updating the chassis. I said we’d been looking at the rules and you only have to make 50 examples to keep it production legal for the racing class. I added that it could be water-cooled. I did the math and told them a 1,000cc twin will beat a 750 four-cylinder, and so off I went and called the guys from Cosworth here in the US because they had a 300hp 3liter engine. I projected a bit less than 150 horsepower because of the V-twin, and ended up with 140, and that should be enough to win and of course, a V-twin is more driveable. To increase the horsepower further, The Cosworth guys said that to get the horsepower you need an airbox 12 times the size of the cylinder displacement, because each step you take out of the airbox, if it isn’t gigantic in volume, you’re pulling a vacuum - otherwise it’s the opposite of a supercharger. if the airbox isn’t gigantic in volume each time the cylinder takes a gulp, you’re pulling a vacuum so otherwise it’s like having the opposite

of a supercharger. So 12 times the volume required a 6 liter box, so that’s the size of a gas tank! Because of that I put the gas in the frame for the first VR prototype I built for them in 1988.

Erik I used to race a Ducati 900SS which was lovely but the Yamaha TZ750 I raced was very different. The TZ750 actually was the better handling bike because the problem with the 900Ss was that you sat too far back. I’d have to climb on top of the long tank and muscle it around. So I built it compact to have the rider up forward and a steep steering angle. I also split the radiators to get the front wheel as close as possible, considering full braking and fork deflection. So that was the idea of the original VR, and Harley started work redesigning the engine within those parameters. They hired a guy from Rausch and he felt this didn’t make sense, so development took longer than expected. I got a phone call from the AMA in December saying 'one of your executives says you’ll be ready for Daytona in the Spring', and they didn’t even have a running engine yet, so I said “hell no”. H-D’s V.P of Engineering, Mark Tuttle, called me up and said “You’ll never speak on behalf of Harley-Davidson again you son of a bitch, you’ve embarrassed me because I told them we’d be there.” I told him they weren’t going to be ready on time and he told me I was not allowed to speak on their behalf, then they threw me out. They brought in a guy from England to design a beam type frame, and then threw out this squirrelly tube frame that this guy from Michigan had built. The beam frame was pretty good one and the engine made good power on the dyno, but not in the bike, because the airbox wasn’t big enough. It would work on some tracks but the chassis was too long and the guys really had to fight the handling as a result.

JL I ran a 600 and 750 Supersports team back in 1995 and 1996 and got a chance to see nearly every track in the country and watch the VR struggle throughout the season. It blew me away by how big and bulbous the VR looked fully clothed and how absolutely tiny it was once the bodywork was off. The handling seemed fine but the reliability wasn’t there. It was disheartening to watch, knowing that it was not ever going to match the Japanese Superbike competition.

Erik It was a shame because they spent massive amounts of money but they were spending it wrong. They weren’t very organized. I got thrown out of the project but I was busy building Buells by this point. I suggested they let me run it as a Buell project but that didn’t happen. Well, on to the H-D purchase of Buell later. In 1993, Vaughn Beales (CEO and chairman of H-D at the time) called me and said, “You remember when you had your exit interview when you left Harley, and you told me you thought the cruiser business wouldn’t last? He told me he had gone out and talked to customers, not staff, not dealers but people who were more emotional about the bikes. "I saw this huge number of potential customers just gathered around this customer bike this dealer had built and they loved it”. It was like a 1930s classic style. He said, "I’m buying Buell for two reasons: one is that the economy will go up and down and the age of the biker will, too. If I chase volume and price I’m going to destroy this Rolex brand of ours. I need you to build us a sportbike for the guys who never are going to be as wealthy as the old guys who were celebrating their own youths and would spend big money on a Harley. I want to get them while they’re young and that’s what your brand is for me.” Well, you can’t fault that logic.

Erik To make a long story short, when H-D bought Buell the VR had not yet started racing. I went to Daytona and I said, I know you want build Buell's image as a sportbike brand. I said, I know you want build Buells image as a sportbike brand. Why not let Buell be involved in the VR? You know that’s where my heart and soul is, and I said secondly, if it’s a Buell powered Harley-Davidson, then it’s my fault if we have problems and people will forgive me as we’re just a little start-up. I’m trying to be an American sportbike brand. It’s a great way of protecting the mothership. I’m not good at business or being a CEO but I understand motion and I understand technology so those are the two things I know well.

JL You know how to look at things from a different perspective and that was what I think brought a lot of interest for people my age who were interested in a Buell. Things like the underslung muffler, perimeter brake, fuel in frame, oil in swingarm designs, were those born out of packaging necessity or did you see them as performance enhancing?

Erik It is both of those. It was never because Erik is adamant that the fuel should be in the frame of a motorcycle, it was because if you’re building a high performance v-twin there’s nothing else you can do for placement. We’d already seen what a mess it was for Honda and Freddie’s GP bike to put fuell on the bottom of a bike! We wanted to build a bike that delivers what the customer wants - whether it’s a Superbike racer or whether they want an adventure touring bike. They were different customers with different needs so you need to engineer for that, and you should do it in the simplest way possible. That’s why I’m a believer in eliminating parts and making things simple. There are so many advantages to making things simpler from a design and manufacturing perspective.

JL When you started production were you disappointed in the numbers made or was it easier because you were looking forward to the next model and integrating changes?

Erik It’s actually kind of funny, I guess we were happy at about 300 bikes a year and the nobody expected the Buell S1 Lightning to be a hit except me. When our Italian distributor (who was also the distributor for Rolls Royce and Triumph in Italy) saw the S1 at the dealer show, he came over to me and says; “What is this one? This is such a stupid motorcycle, I will sell a million of them. It’s perfect, a big v-twin engine and a tiny seat.”

Erik I just had a feeling that somebody wanted a XR750 for the street which is kind of what it was. Big rear tire and a little bitty seat like the flat tracker.

JL I remember that I couldn't stop looking at it and had to have one. It was short, aggressive and muscular. It was the perfect bike for those Sunday morning rides with the guys. Speaking of Buells of that era, my brother actually flat-tracked a Buell Blast at the Timonium, MD indoor races and at Gratz, PA.

Erik That was a cool little engine that was not supposed to end up like it did but that was an entry point for the brand and was supposed to be a whole series of bikes. None of that ever happened, through an indescribably horrible, stupid reason which was related to some executives at Harley, that ended up doubling the price we had to pay.

JL So Harley was actually making money on the engines but Buell was losing money on the Blast at that price?

Erik They bought a plant and geared up for production estimating 500,000 annually despite me raising my hand at meetings and asking, “what if it doesn’t go that high?” But they said they’d done surveys and you’re a fool that you don’t see the big picture like we do. The plant was equipped with wildly expensive machines not even running. They had this massive overhead and jumped the price from $1080 per engine to $2300. On a bike we were supposed to sell for $3900. That didn’t leave much margin to finish the rest of the bikes when you should be at 40% of the retail so that didn’t leave much room for marketing and stuff you needed to do. The same happened with the XB model. We were losing money as a result of this.

JL When new management at Harley came in and pulled the plug on Buell in 2009, were you relieved that it was over or was it heartbreaking?

Erik It was very, very sad to see what a mess they’d made of it. Between the unions and the fact that most Harley-Davidson dealers weren’t Buell dealers, it looked like we weren’t making a profit so they were trying to fix the entire company. It’s just such a tragedy because a lot of people lost their jobs and all those cutbacks that happened within the next ten years. I’m not a CEO type, I was just a guy starving making bikes. Vaughn Beals turned that company around in ten years, making it one of the most valuable brands in the world.

Erik In the short run it was successful, but it failed as a business. I got to build the bike I wanted within 90 days that summer and it was competitive as a Superbike. Heck, its been successful years later on the racetrack. It’s great to see guys like racer Geoff May can still win races at Barber, beating the KTMs and Ducati. It’s always been my dream to have a real American sportbike, not just a superbike racer. Racing’s good for the brand and credibility. Maybe I’m an optimist. I tried too hard and I wish I’d been a better business person. I should’ve been calmer and more measured, but I was ready to start when they said let’s go, I was ready to go (start EBR).

JL There are enough marketing and business majors in the world, but there are very few innovators, and that’s certainly been the hallmark of your personal brand. You’ve brought innovative products all along including EVs and Fuell and Fllow.

Erik I partnered up with with a French company on that. I was trying to find work for a couple of the engineers that were out of work and started a little consulting business. We did some design work and analysis for a French/American guy after they got a motorcycle design he wanted us to review, and basically we ended up telling him that they could not produce it and make money on it. I and the couple engineers on the side came up with several trick designs and was always interested in electric bikes ‘cause I’m a believer that someday we’re going to run out of dinosaurs, you know? Anyhow he and his friend Fred Vasseur started Fuell to produce those designs.

Erik You know, building $30,000-$35,000 Superbikes is for a very tiny market, but you only do it for one reason, and that’s passion. You will never make money doing it. I told them that we could design e-bikes but that’s not the same as electric motorcycles.

JL But you did end up creating E-bikes and E-motorcycles

Erik Yeah, but what happens with electric motorcycles is that you have as much drag as a car you know? Your front is low but your CD (coefficient of drag) is big and that’s the truth. The total drag is pretty high so when you’re rolling down the highway at 70mph you’re burning as much as a car. A Tesla goes 300 miles but needs a 100 kilowatt-hour battery and let me tell you, that weighs a lot, and you can’t do that with a motorcycle - yet - as efficiently. You can’t run sustained high speeds that long anyway if you’re in an urban or even suburban community. Electric bikes are crazy fast for the city. For getting away from stoplights and zipping around the traffic it’s awesome and you’re not going to have range anxiety in that setting. So the decision for those guys to start Fuell came at a conference in Paris where the keynote speaker flew around the world in an electric airplane. With the mayors of Paris, Barcelona and Berlin, and the bankers there was Formula E cars racing around a track, lots of caviar and champagne kind of event. The talk was of eliminating the internal combustion engine engines in the cities. I thought “holy shit guys”! This was it, this is what we need to get things going. You could replace all those gas-powered scooters because you know, even in Italy people have the Ducati 1199 for Sunday but they commute on a 500cc bikes with bags or a scooter. That’s what they ride every day and I thought that this could work. If you could do something that looks like a Ducati sport bike with storage so I went back and started designing it for them. I went back and designed a second generation a bit later before retiring. Not long after I saw they went under and it’s frustrating, it just breaks my heart for so many reasons. I hate this type of thing because people get hurt when these things happen.

JL It seems like the LiveWire had two things working against it, with both limited range and a high price.

Erik Yeah, customers did not embrace it, so unfortunately it’s one more electric motorcycle going down in flames. It’s too bad, cause many people thought customers wouldn’t like electric motorcycles but when they found out what the performance envelope was, they felt it wasn’t going to work for them if they can only ride it for a bit on Sunday. Now those two big trips I want to make a year are out of the question. You’ve got to make something that delivers fundamentally with the customer. If you want to build a commuter, it’s got to be economical, you know?

JL You’ve led an amazing life so far, but I feel there’s still more to come yet.

Erik It’s very satisfying to make a connection with people of all types.

JL Indeed, connecting through music and motorcycles, what could be better?

With that, I hung up the phone and sat back in my chair to absorb the moment. Erik Buell has managed to achieve the great American dream by sheer force of will and determination. Despite the ups and downs, he’s still a wildly optimistic guy with an abundance of energy and talent. In the rough and tumble world of motorcycle design and manufacturing, few others have achieved this success.

Erik Buell will be the Honored Guest at the upcoming 28th Radnor Hunt Concours on Sunday, September 7 in Malvern, Pennsylvania. More information is available at www.radnorconcours.org

The Man Who Rides Them All - Alan Cathcart

Meeting Alan Cathcart at the annual Team Obsolete Christmas Party was a thrill. He's had quite a career. We have a few mutual friends and that opened the door for easy conversation. It didn't hurt that I wore my FB Mondial jacket, as Alan famously owned an ex-Mike Hailwood 250 Mondial, that he eventually sold to buy a Ducati Supermono...as one does. The following is an edited transcript of my chat with Alan Cathcart on December 9, 2023:

Alan Cathcart (AC): I'm a reader who decided that I'd go out and try and find the bikes that I've read about, and write about them. I’m very fortunate to be somebody who made his hobby his livelihood. It began while I was in the travel business. I was a partner in a wholesale group travel company and traveled a lot in the USA. Because of that I was able to dig up some pretty interesting motorcycles and take them back to Britain. I started racing in Britain in the mid 70s thanks to an American friend of mine, Jeff Craig. Jeff had come over to England with a tour group from his school and he’d come to get parts for his 1937 MG TA. When I rolled up at the at his hotel to supervise their half-day tour of London, he saw my bright red MGA and decided we were bosom pals - and that I’d be able to him get parts for his TA. I did and we became very good friends. He then decided, having graduated, to come to England and learn how to race motorcycles that turned right as well as left. He was a flat tracker! We shared an apartment in central London and started racing. In fact, I was racing cars back then and just the thought of going into Paddock Hill bend at Brands Hatch on motorcycle filled me with dread.

Classic Bike did an article about all the British Formula 750 BSAs and Triumphs with Rob North frames and 3-cylinder engines, but they missed mine because I’d found it in Houston TX. I wrote in to say they'd forgotten about mine, and by the way, why didn't they include some racer tests in the magazine like they did in Classic Sports Car with Willie Green? Editor Mike Nicks said that's a great idea: we'll mention your BSA in the next issue, and why don't you do the racer tests? Me? Look at a page of blank paper in a typewriter? He eventually convinced me, and the first article I ever did was about my G50 Matchless. I tested a couple of bikes from my own collection and the readers response was great – ‘Would you like to ride my bike?’ And that's how it all took off.

AC: Yep, Spa Francorchamps in Belgium when it's dry. Unfortunately, Ardennes weather means you frequently get all four seasons in one day, but I've always liked big circuits. I like Monza as well because you can gain seconds in fast corners not only by being brave but also by making sure you get your lines right - Spa rewards that in spades. It's a great, great circuit.

AC: My girl Trixie is sitting in my garage and looks at me every time I open the door. This was a lovely story because it came about when Yamaha produced this bike for the Japanese enthusiast. The idea was you get a base model sports bike using their existing Super Tenere engine designed for African races and they produced a used to sports bike. They had no idea it was going to be successful in Europe, so before taking decision to order it, Lin Jarvis, today the Moto GP head of racing had the idea , let's see if we can find a journalist who would like to race it in the few Pro Twins races to see what the public thinks of it. So he asked me and I said yes! So he commissions Over Racing, which is the back door of the Yamaha race shop, an independent tuning shop in the same way that Morawaki is the back door of Honda and Yoshimura is the back door for Suzuki. Over Racing produced Trixie and I won my first race on it in the pouring rain at Assen by 20 seconds and had a huge amount of success with the bike that was a beautiful, beautiful ride and still is today. I'm glad to say that Yamaha Europe thought it was so successful they imported it for the second year. It became a cult motorcycle.

JL: And you took Trixie to Daytona?

AC: Well, my reward for winning so many races on it the first year was that Yamaha Europe paid to take it to Daytona. Nobody had seen one before, because the TRX was never imported to America. Yamaha USA bet all their bucks on a V4 cruiser, which was a bomb. I won the Battle of the Twins race at Daytona, coming from the back of the grid because I didn't have any races the year before. I beat all the Ducati Superbikes. Nobody quite knew what this thing was: I remember Richard Chambers, the announcer, grabbing me as I came into victory lane and saying, “Alan Cathcart, how the hell did you guys make this motorcycle out of a dirt bike?” I didn’t do it, Over Racing did.

AC: I'm very fortunate that factory race teams allow me to track test their designs, one year after another: that means I went fast enough to demonstrate I knew what I was doing, could evaluate the bike properly, and never tried to show them I ought to be racing the bike next week, instead of their current rider. Secondly, my articles were very long. I was sorry for my editors, but it’s my duty to report everything that anyone would ever want to know about that particular bike. The engineers really did appreciate it: I told their stories, even if it was a bad season. Full marks to Honda, they let me ride bikes even when they were fundamentally flawed. That was the key to being allowed to test these bikes. In the case of Superbikes, the time came that I could not register a qualifying lap time, so I stopped racer tests in 2015.

JL: And in 2009 you were awarded Journalist of the Year by the Guild of Motoring Writers based on your evaluating ten of the best GP bikes and World Super Bike racers. This was the era of Valentino Rossi, Jorge Lorenzo, Danny Pedrosa and Casey Stoner. How did you convince the factory teams to allow you to test them that season?

AC: Well, it got to the point that I didn't have to ask, they would come to me to ride the bikes. “Are you free to come to Suzuka on such and such a date?” I have, dare I say, proven my bona fides and my capabilities by the articles that I've done.

AC: That was Eddie Lawson’s 1989 500cc World Championship winning NSR 500 Honda V4. Eddie was the first person ever to cross from one Japanese manufacturer to another with the number one, in 1989, having won it on a Yamaha in 1988. I had watched the evolution of that bike, so I had my annual invitation to come to Suzuka in October at the end of the season to ride the bike. In those days we didn't have tire warmers so we had to do a slow lap, gradually speeding up before giving it the berries on lap two. I came out of the chicane at Suzuka before the finish line and it's a long, long third gear right-hander past the pits. I got on the throttle hard and the bike tried to kill me. It got into a massive tank-slapper and by great, good fortune I stayed on. I can't say it was anything I did. I was sure that something had broken so I toured ‘round slowly and came back to the pits. As I came down pit lane from mechanics were all bowing very, very low which Japanese way of saying “I'm sorry, I apologize”. So I stopped and I said “you saw what happened”. “Alan san, we are very sorry, we forgot to tighten the steering damper that on removing it from the truck. Okay, so my fault. I should have checked. They tightened it up and then, okay now I said, “I can't steer it, the steering is solid, I said. “Yes”, they said. If I have a slide I can't correct it. “Eddie san always ride like this”. Oh, so I went out and I can't claim this was a proper test, this was showbiz. I was getting some photos, getting experience of what the engine and chassis wasn’t really... I'm trying to find a polite word, ready? Obviously, Honda knew this. So I wrote the article and I explained what happened. By the way, it was always a condition of my tests that the manufacturer would strip the bike for photos and let us take pictures of what it was like behind the fairing, with the fuel tank off. That's when I saw what I really noted in the Grand Prix’s how the the welding around the steering head on the Honda was so built up, about three or four different levels of metal level. Anyway, I wrote the article and remember seeing Eddie at the Bologna show at the Super Moto race sitting on the back of this Transit van and I walked towards him. Every step I got closer we got another 10mm of Eddie Lawson’s smile. As I came up, he said “I hear you rode my bike”. I said yes, it tried to kill me. “Join the club”, Eddie said. So, next year I get my annual invitation the article is published all in the world. My invitation comes from the Head of HRC. He said, “Alan san, first can we meet at the railway station restaurant in Tokyo before you come out to Suzuka?” Went to a nice Italian restaurant, had a very nice lunch and chat and then the coffee arrived. Two hands on the on the table and Alan san, I must tell you that this year we had some difficulty to convince Honda public relations staff you should be allowed to test our bike. I said, Oh what, last year's test of the Eddie Lawson bike? He said, “Exactly. And I told them Alan Cathcart always writes the truth, he will test our bike again this year because he always writes the truth, and by the way it was not a good motorcycle.” That was a nice vote of confidence.

AC: Well, Ducati has been working at it and it's exactly 20 years. Funny, I've just republished my article on the 2003 Ducati Desmosedici GP3. That was their first attempt at going Moto GP racing with an electronics light, doubled-up Superbike: That was essentially what it was obviously scaled down in plastic. But I’d liked to be a fly on the ceiling of a Honda Board room at the end of the first lap of the first race last year and Suzuka. When Loris Capaossi came round in the lead at the end of the first lap on the Ducati. The very first lap of its entire Moto GP career. And the 2nd, and the 3rd, and the 4th, and the 5th, with all the title winning Honda RC211 V5 cylinders behind it including Valentino Rossi's. Eventually, the lay got passed but Loris still finished third and he won the sixth race at Catalonia. Finished third in the championship his teammate Troy Baylis fourth. That was the beginning of a process that has followed that management and since 2010 with their owners Audi/VW. They have kept faith with the whole project. They did have the success of Casey Stoner in 2007, the first year of the Honda-inspired 800cc formula but no it's not the same as dominating the grid and the results as we've done this year.

JL: They came to learn Valentino Rossi desperately wanted a seat on what he thought was the secret weapon of Casey Stoner, but it wasn't the Ducati, it was Casey Stoner. It's different this time.

AC: It's different now because there were seven different winners on Ducati’s this year and that shows what a great bike it is. Come on, well done Ducati! Now it's up to the others to try and match them.

AC: That’s a tough one. I suppose to a certain extent it depends on the bike specification. Is the specification or interesting? Is it unusual? To what extent do I need to explain that to the reader? Every bike has its own hook, its own reason to be written about and it's just up to me to try and get that over to the reader in the first paragraph; that's the most difficult part of every story. Write that first paragraph and hopefully I've hooked you and you want to read the rest of it.

JL: So you've seen motorcycle journalism evolve over the years. What are the notable changes or trends you find most significant and how would you define your style of journalism?

AC: Mine’s an old style of journalism because I write lengthy articles. That is the single biggest difference between now and 40 years ago when I started. Reader retention, the reader somehow or other doesn't have, allegedly, have the attention span they had 40 years back. They want shorter articles which is strange in a way because print is increasingly being replaced by online, by digital there's no space limitations on digital. I still write long because it’s up to me to tell you, the reader everything you could possibly want to know about that particular motorcycle.

AC: I believe that there will be coexistence. The aim is net zero. Okay, it's a very valid aim. But we have to think about how this electricity is produced. Electric vehicles are zero emission at the point of use. Frequently it has been a huge amount of carbon created by the manufacture of the current, particularly in countries like China and India which seem to be building a coal-fired power station every week. Great if it's nuclear, but nuclear has its own risks. In any case, the European Union which at the moment is one of the key drivers of product development on two wheels. The European Union under pressure from the European motor car industry has modified dictate there should be no new ICE internal combustion engine vehicles sold and registered in the European Union after 2035. From now on it will be either be zero emissions at the point of use or else there will be ICE vehicles permitted so long as they're powered by digital fuel, E- fuel. So fuel is not manufactured by fossils components. I believe that there will be a coexistence in the future between the two types of products. Electric vehicles will become cheaper to manufacture than IC ones simply by the economies of scale. But at the point that's company like BMW Motorrad, BMW motorcycles the largest prestige manufacturer in the world of two wheels, they have stated that they will continue to make IC models after 2035 which will be obviously powered by digital fuel. It does give the consumer a choice. This particularly will apply for certain kinds of model which they have stated through an interview I did with the recently retired CEO Marcus Schramm. He stated that we believe that there are certain applications for motorcycles which can never be electric powered and a good example of that is adventure touring. Well since that represents the biggest single model segment at moment in mature markets that's a pretty important statement. So we'll still be able to buy an Africa Twin we hope or BMW R 1300GS by 2035. That's a very rational policy.

JL: So you feel that the market is still going to be receptive to it as long as there is some offset of the carbon footprint?

AC: At the end of the day what matters is the carbon footprint. If you take into account the ingredients represented by the manufacture of the fuel, whether it's electric fuel or whether it's liquid combustion fuel that's still the most important end result. People who ride bikes tend to be quite conservative and oh, it doesn't make a nice noise, so I don't want it. Well, I can tell you there are some electric motorcycles which are thrilling to ride simply because of their sound quite apart from this the fabulous acceleration you get. The best example I can give is the MotoCzysz which won the Isle of Man Zero TT Electric race four years in a row and beat Honda, otherwise known as Mugen each time. The MotoCzysz, which I was fortunate to ride at Portland Raceway screamed at you because it had direct, straight cut primary gears. And it was a thrill to ride! It handled really well and MotoCzysz really knew chassis and suspension design so well.

AC: We own a house in Western Australia and so we go there each year, my wife Stella and I for three months in January – March to escape the British winter which is not necessarily cold but it's so true we get a lot of dull wet days. While I'm in Australia there’s a huge number of exciting and interesting bikes built out there, like the Drysdale V8 to the Motoinno TS2 Triumph Moto 2 bike. I’ll go and ride those and write about them. I’ll come back to Europe as a rule for the Goodwood members meeting on April the 15th weekend when I’ll be marking the 50th anniversary of my green frame Ducati 750SS by racing it in the formula 750 race. We’ll give her a nice birthday party. I've just published the second of my two books about Ducati Superbikes 1988- 2019. The same publisher in Italy has asked me to produce a book on a very famous American. His name is ‘Doctor John’, the story of the John Wittner Moto Guzzi V-Twins and his rider, Doug Brauneck. Lastly, I’d like to say out there to readers thank you for all your support down the years and please just keep on reading my work, I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I enjoy writing them.