The Golden Age of supercharged racers was a brief but glorious moment, when competing factories built ultra-exotic machines which laid the foundations of modern motorcycling. By pushing the boundaries of engine and chassis technology, new designs were adapted out of necessity, like perimeter frames, front and rear hydraulic suspension, wind-tunnel tested fairings, etc. The power discovered through forcing an air/fuel mix into an engine – a 40% gain in HP, at best – revealed problems with high-speed stability and wind-cheating which are still being addressed by ever-faster sport bikes.

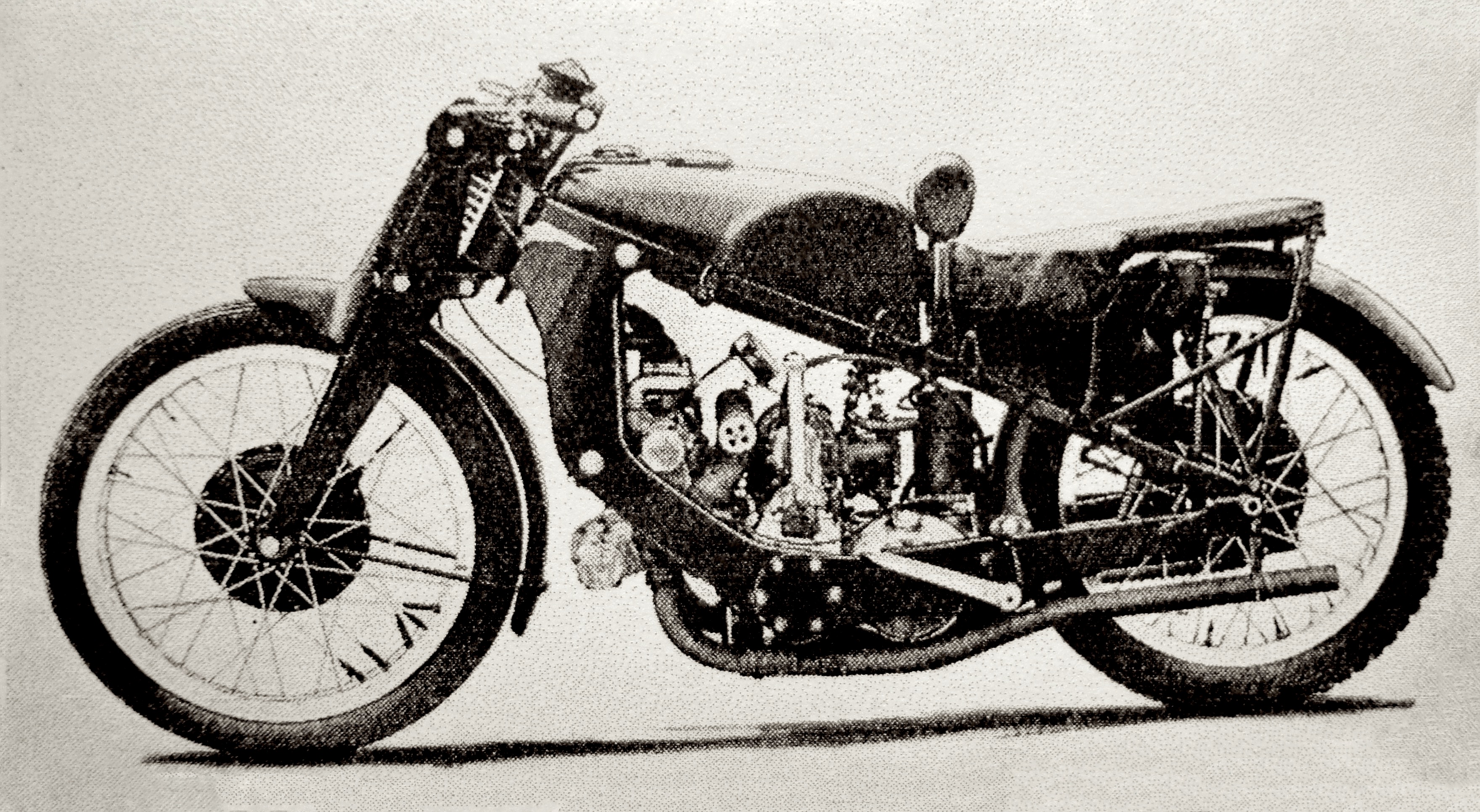

The German and Italian factories were the first to embrace supercharging as a race policy, and integrated blowers with their racing engines from as early as 1925. By the mid-1930s, all companies competing in the Grand Prix series were at least experimenting with blowers and multi-cylinder engines, barring Norton, who remained true to their naturally aspirated single-cylinder racers. While AJS had a blown V-four, and Velocette a blown vertical twin (the ‘Roarer’), these machines were underdeveloped compared to their competition from BMW, DKW, NSU, Moto Guzzi, and Gilera, whose racers dominated the high-speed stakes in every racing capacity – 250cc and 350cc for the Guzzi flat-single and DKW two-stroke racers, 500cc for the BMW flat twins, NSU vertical twins, and Gilera 4s.

http://www.britishpathe.com/video/150-miles-an-hour-on-a-motorcycle

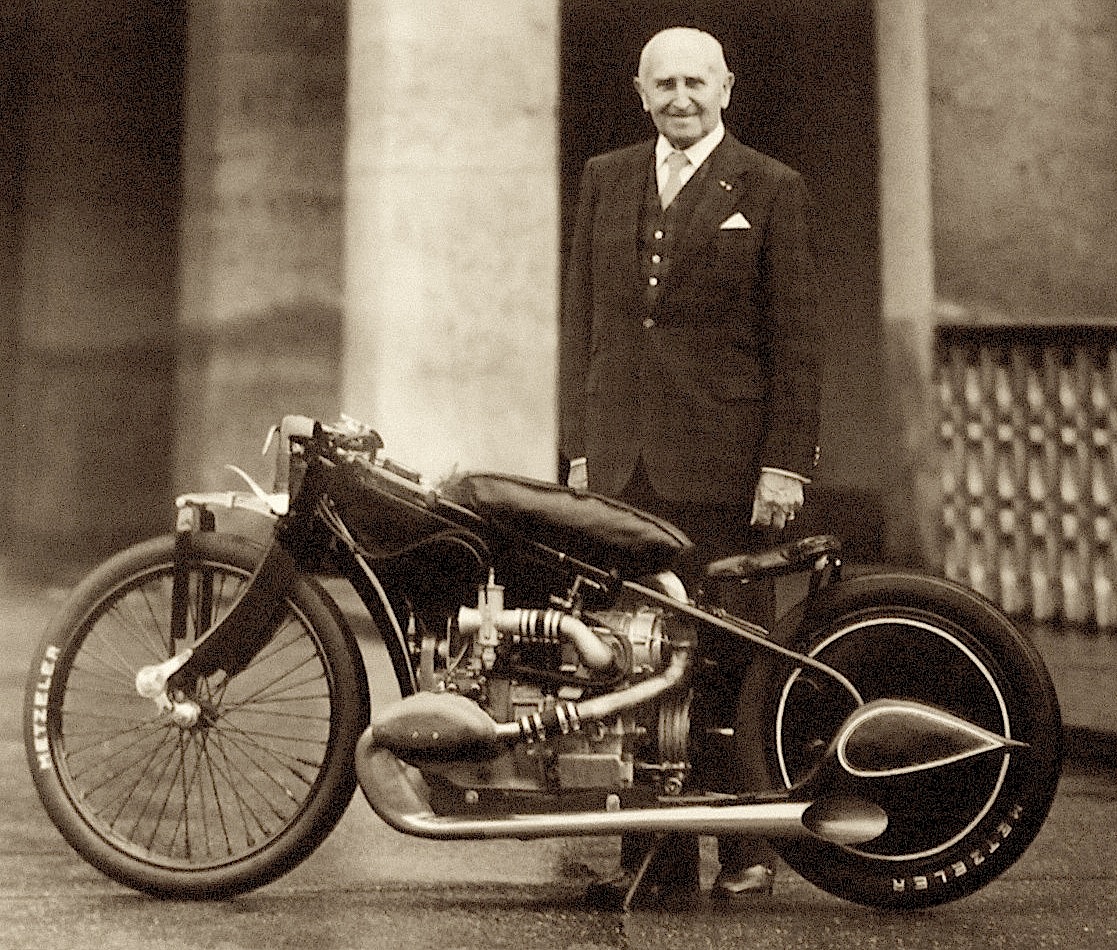

The World Speed Record was the sole property of supercharged motorcycles from September 19 1929 onwards, when Ernst Henne took the first of his many records on a blown WR750, with a pushrod 750cc motor based on the BMW R63, on the straightaway at Schleissheim, Germany, at 134.68mph. Henne’s record was challenged the following summer by Austrian Brough Superior importer Eddy Meyer, who added a supercharger to his SS100, and a new JAP 8/50 racing motor, but French customs officers refused to import his special racing fuel, and he never reached the speeds he intended.

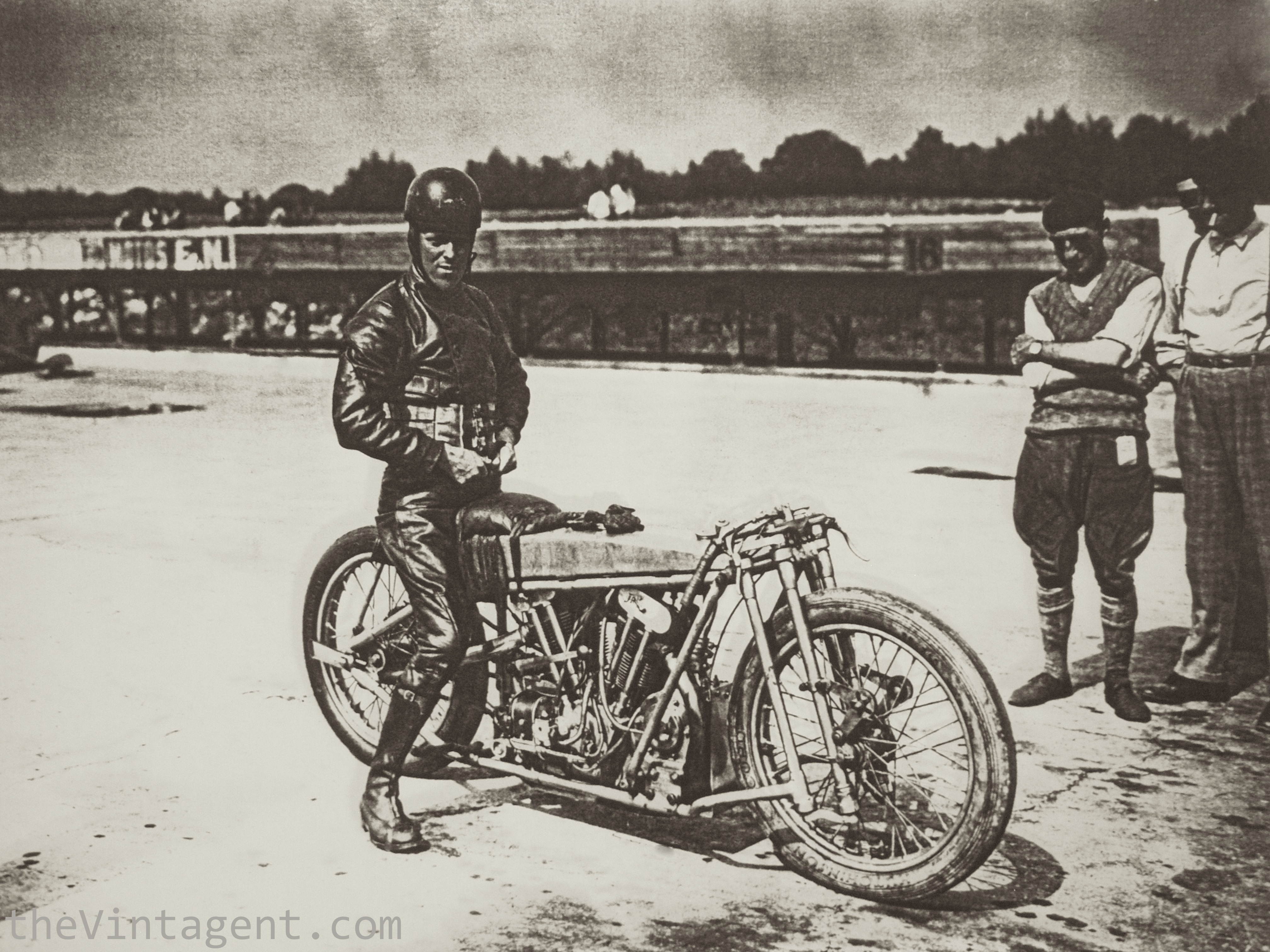

It took Joe Wright on a supercharged OEC-Temple-JAP to beat the BMW’s speed, which he barely pipped at 137.32mph down the straightaway at Arpajon, France, just outside the gates of the Montlhéry speed bowl, on Aug 31, 1930. Less than a month later, Henne squeezed another mph from the BMW, and recorded 137.66mph at Ingolstadt, Germany, on Sep 21st. The remainder of the 1930s was a ding-dong battle between a clubby pack of English speed-demons and the might of the BMW factory, interrupted only by the Gilera Rondine snatching glory for a moment in 1937, when Piero Taruffi recorded 170.37mph on the Brescia-Bergamo autostrada.

The Brit club included George Brough, Freddie Barnes, and Claude Temple as builder/mentors, and Eric Fernihough and Joe Wright at the brave riders. These gents worked in glorified sheds, squeezing power out of the obsolete (by comparison) JAP pushrod V-twin engine, which they housed in their own chassis (Brough Superior, Zenith, and OEC respectively), and ultimately succeeded in retaining glory, until it was clear ‘the competition’ would shortly involve guns. The motorcycles they built are magnificent bitsas, masterpieces of handwork and inspiration, cobbled together by men of tremendous passion. Amazingly, almost all of these supercharged record-breakers survive.

Below is a fantastic ‘5 minutes’ with Piero Taruffi and the Gilera Rondine:

The BMW factory, by contrast, worked from a fresh sheet of paper, ultimately designing the RS255 engine for modern racing, integrating a blower to the engine castings, and developing this OHC flat-twin 500cc racer to win both the Isle of Man TT by 1939, and take the ultimate pre-war World Speed Record by 1937, at 173.68mph, which stood for 14 years. The BMW had half the engine capacity of its rivals from England (although the same capacity as the Gilera, which was only 3mph slower), but had the advantage of a modern factory and a team of talented engineers to build this superb machine from scratch. The BMW record-breakers were equally the product of passionate engineers, and are equally masterpieces of speed-inspired design. Amazingly, the BMW and Gilera record-breakers also survive, and all can be enjoyed in person, if you’re lucky enough to encounter them. In the past two years, for example the Joe Wright blown Zenith-JAP and OEC-Temple-JAP could be seen at the Vintage Revival Montlhéry, as well as the Concorso di Villa d’Este, where one could also see the BMW WR750 and Gilera Rondine in original condition, and a rebuilt RS255 streamliner (‘Henne’s Egg’). These machines are reason enough to attend such events, as they leave a lasting impression as the pinnacle of the Golden Age of Supercharging.