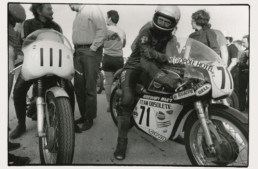

How Speed Work varies on Motor Cycles, in a Car, and in Aeroplanes

[From ‘Power and Speed’, published by Floyd Clymer, 1944]

By Flt.-LT C.S. Staniland

Chief test pilot, Fairey Aviation Ltd, Motor Cyclist and Racing Driver

I suppose that, before I begin writing about aircraft and motor racing, I had better tell you how I first came to be mixed up in this business of fast moving in the air, on four wheels and on two.

Soon after learning all I could about this Douglas I became the owner of my own machine, a Rudge Multi, looked upon in those days as something very hot indeed. It had a single-cylinder engine, belt drive, and a complicated arrangement whereby moving a lever altered the position of the back-wheel driving sprocket and so altered the gear ratio. The result was that with this device you had a very wide variety of gear ratios, with the option of a high top gear for fast cruising.

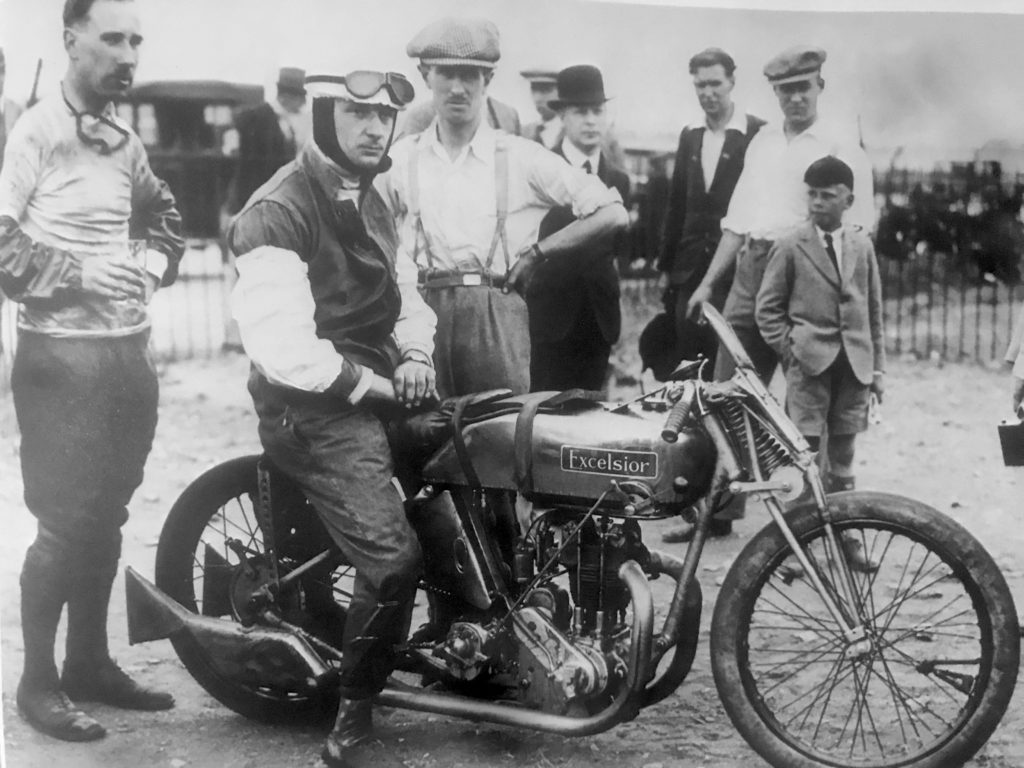

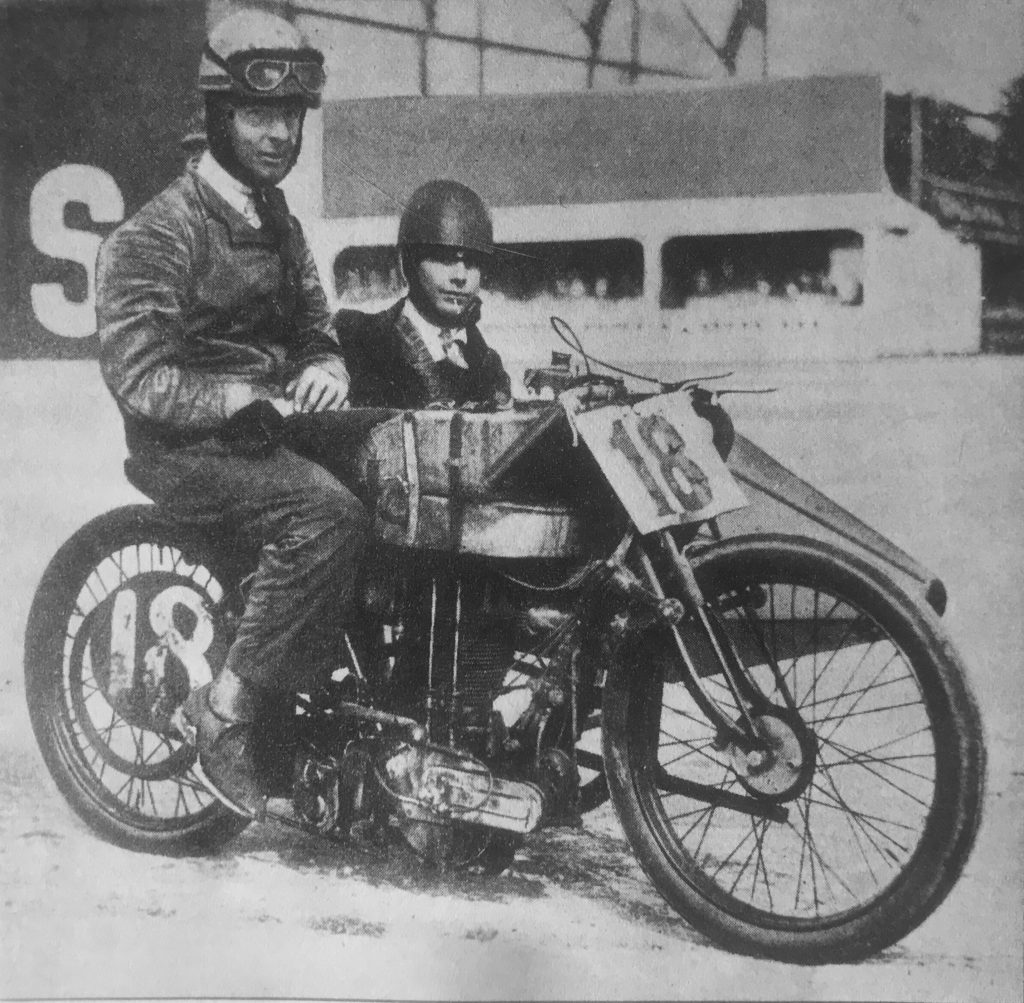

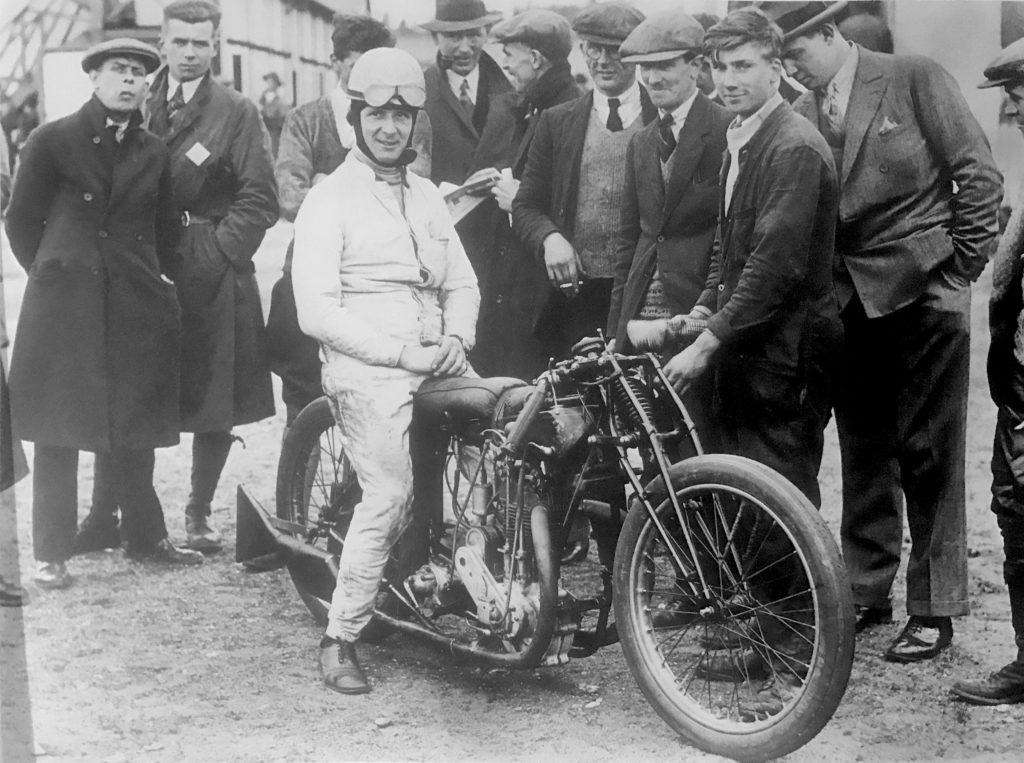

In 1923 I achieved an ambition and raced at Brooklands, and won my first race – a standing start lap at no less than 54mph. I rode Nortons in 1924 and in that year I joined the RAF. During this time I was stationed in Cheshire and raced consistently at Brooklands. Soon after this I began to ride machines for my friend, RM ‘Nigel’ Spring, and we had rather a successful time in the 500cc and 750cc classes, including the breaking of several records.

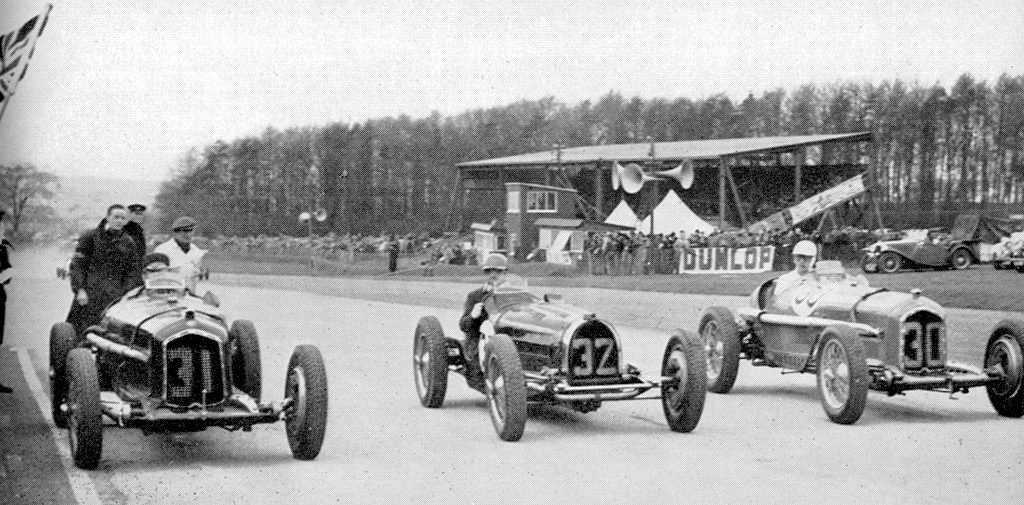

Up to this time I had always looked down on the motorcar racing game but I very much admired a Bugatti of George Duller’s, and in 1926 I acquired a 2-liter straight-eight Bugatti of my own, the second of the type imported into this country. With this car I had a shot at car racing at Brooklands and met with a measure of success. Since then I have raced motorcycles (not so much on the two-wheelers this last year or so, for various reasons) and all sorts and shapes and sizes of racing cars.

As you may know I was a member of the Schneider Trophy team in 1928-29, and then, leaving the Royal Air Force, I became test pilot for the Fairey Aviation Company, the famous aircraft concern.

In both forms of sport there is the same need for perfect judgement of speed, the same gentle touch for braking and the same benefits from experience. A motorcycle has to be ridden – there is no question of a machine keeping itself up owing to its speed. Riding a motorcycle at great speed calls for the utmost physical fitness. When you see a motor cyclist flying down a bumpy road at over 100mph it keeps upright by reason of the skill, courage, and experience of the rider and for no other reason.

The fastest cars are faster than the best motorcycles. The power to weight ratio is about the same in both, but the car has better streamlining. A road-racing motorcycle will weigh about 350lb and will develop about 50 brake horse-power. A Grand Prix car of the 1937 type weighed about 18cwt and gave off about 500bhp. The car has better road holding, better suspension, better braking and greater inherent stability, which all tends to make the car faster on the road. On road circuits where cars and motorcycles both race at various times, the cars have proved the faster, by as much as 10mph on the lap speed.

The motorcycle record for the standing start kilometre is 98.9mph whereas the car record for this distance is 117.3mph [this is 1938… ed.].

Racing motorcycles will develop as much as 120 or 150 horse-power per 1000cc of engine size, but the latest Grand Prix cars will exceed this. Most racing cars have supercharged engines, producing astonishing power from small units by this means, but supercharging has not yet caught on in the motorcycle world owing to special problems of carburetion, added to which although a supercharger can be mounted on a motorcycle quite neatly, it absorbs some power in the drive and the extra power produced seems offset by the power used up in the driving.

The carburetion problems of aircraft are far more complex than either in a car or a motorcycle. A car operates always at about the same barometric pressure, so that carburetors can be tuned with precision for every given racing circuit and left at that for the race. An aeroplane needs carburation for varying barometric pressures and for varying temperatures according to the height at which the aeroplane is flying, added to which the carburetion must be right for all weathers, including frosty conditions. An aeroplane starts off from sea level and is called upon for maximum speed at say, 20,000ft, where the weight of air drawn into the cylinders is far less than on the ground. Every tourist knows how his motor car loses power in climbing a high Alpine pass of perhaps 6000ft, owing to the fall in barometric pressure which allows the mixture to become too rich. An aeroplane at 20,000ft would in the same way have a hopelessly over-rich mixture and would lose a great deal of power at what is its usual service altitude.

Aero engines resemble car engines in all essentials, but are much more expensively made, with the finest procurable materials, the best labour and with exhaustive tests, which all send up the price. A racing car engine is tuned much nearer to breaking point than an aero engine, and after one race has lost its fine edge of tune and has to be inspected and perhaps reconditioned. Thus after a Grand Prix, the German cars are sent back to the works for inspection and re-tuning, while a different team of cars is sent out to the next race. An aero engine, on the other hand, must be capable of giving off its full power for very long periods with only routine maintenance – checking of valve clearances, plugs, filters, and so forth.

Speed on two wheels feels colossal. A car feels slower at 100mph than a motor-bicycle at that speed owing to the rider of the latter being exposed to the wind and being much closer to the ground flashing away under him.

But 100mph in a car feels far more exciting than an aeroplane at 300mph – and many RAF aeroplanes will do far more than that flying straight and level. It is extraordinary how, after flying at high speed and the pilot comes in to land at 80mph, the machine appears to be crawling. Reduction from high speed to low velocities is always deceptive, as one mechanic found out at Brooklands when his driver slowed down to 30mph and the unfortunate man stepped out under the firm impression that the car had nearly stopped.

Great comparison article. I always thought that motorcycles were inherently faster than automobile racers and they may be now over the same road courses, but this article really puts you in the driver’s and rider’s seats. I was just up in a light plane and it seemed by comparison very boring until we hit ground and slid a bit sideways. Nothing seems more exciting to me now than racing my ’26 Indian due to my very intimate relationship with the track at speeds close to 100 mph.

Thank you for this. Very good reading.