The rusting remains of an old motorcycle on the edge of a Vancouver Island property stirred rumors for years. Nobody could prove it, but they might be the bones of Barking Betsy, a machine at the heart of a story lost for a century.ADV:Overland celebrates the spirit of adventure and exploration. Our Petersen Museum exhibit runs from July 2021 – April 2022. These are the stories behind the vehicles in the exhibit, and others we need to tell because they are amazing, like this nearly forgotten story of a pioneering naturalist making his way across the USA in 1915.

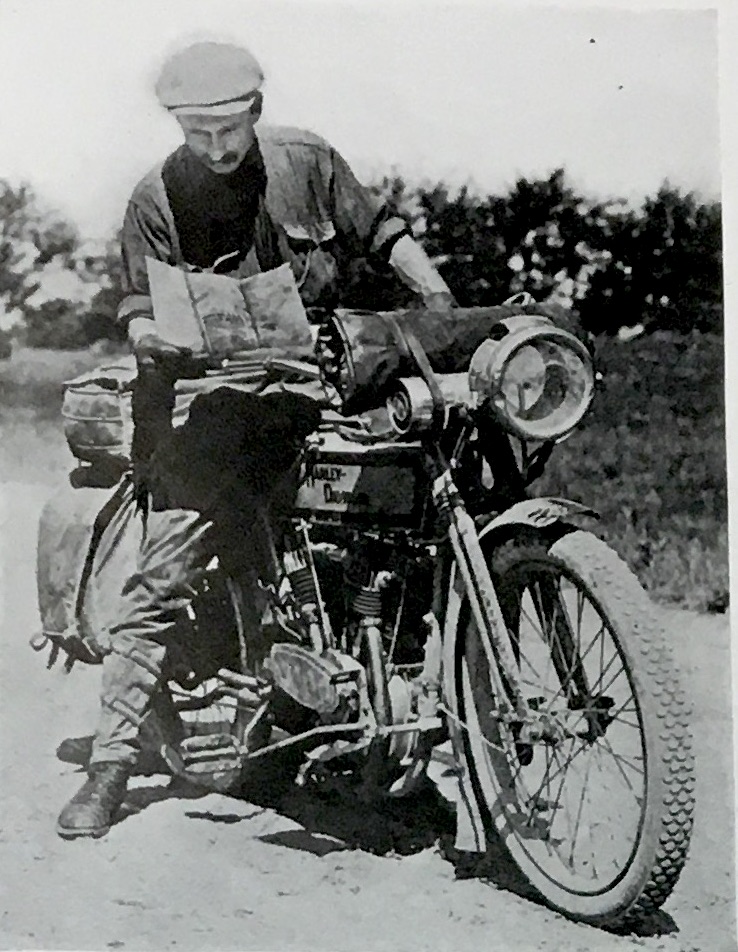

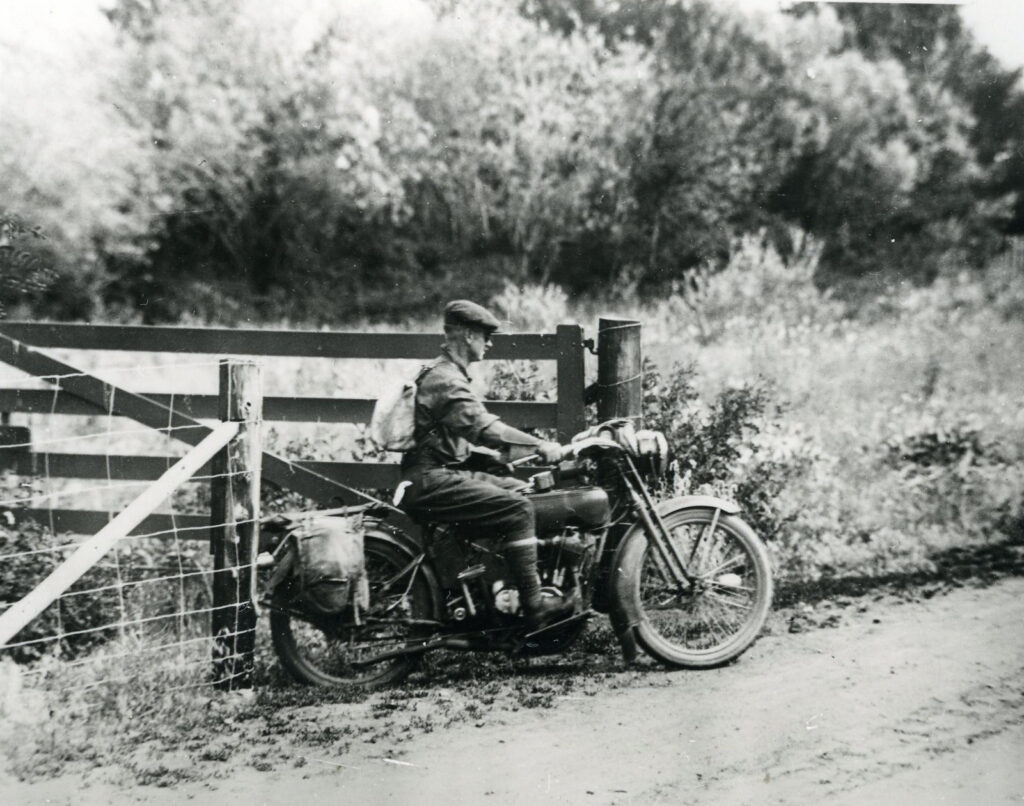

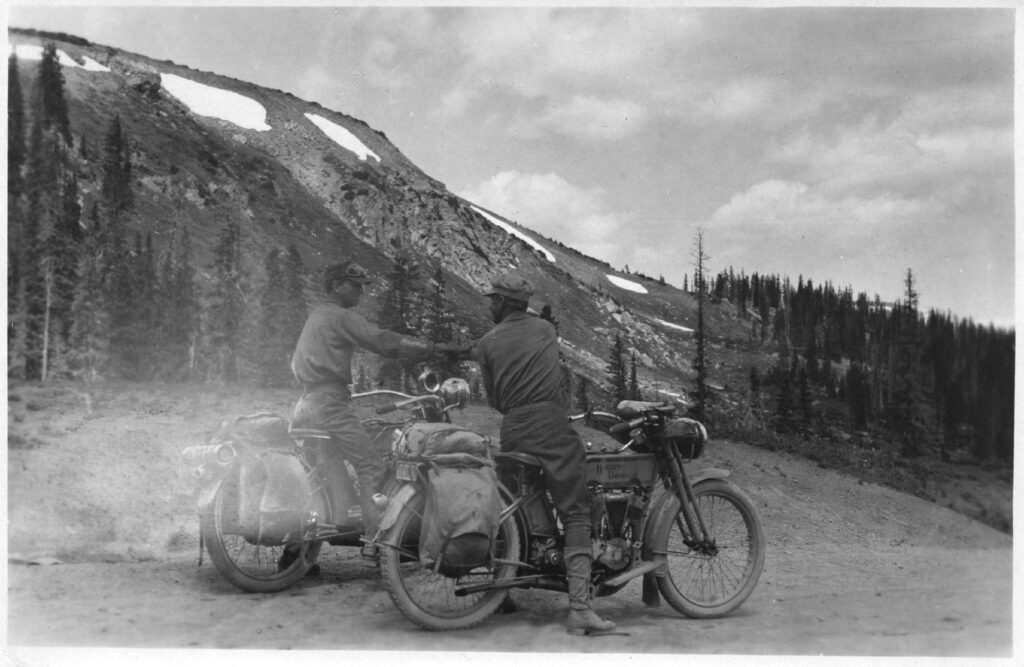

In 1915, Hamilton Mack Laing rode his Model 11-F Harley-Davidson, nicknamed Barking Betsy, from New York to San Francisco to see the Panama Pacific International Exposition, carrying on northward to Portland. Over the winter of 1915, Laing used his handwritten notes gathered on his journey to produce a manuscript, but waited until 1922 to send his 148-page story to Harley-Davidson, thinking they might serialize the tale of his epic journey in The Enthusiast magazine. Perhaps his story was too old by then, as Laing’s article went unpublished, and his story forgotten.

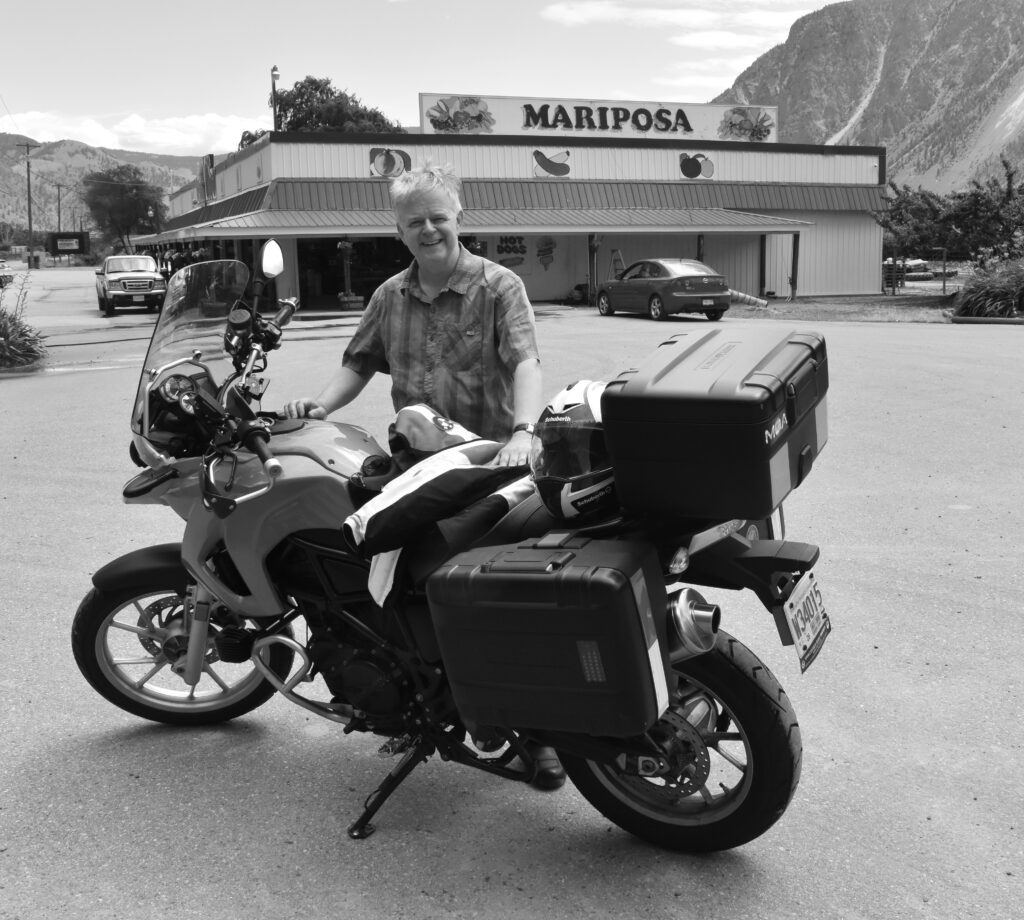

More than 100 years later, Vancouver-based author and motorcycle travel writer Trevor Marc Hughes learned of a manuscript resting in the British Columbia Provincial Archives in Victoria. Realizing the significance of the story, he worked with publisher Ronsdale Press to bring Laing’s story back to life. Better late than never, Riding the Continent was released in the fall of 2019.

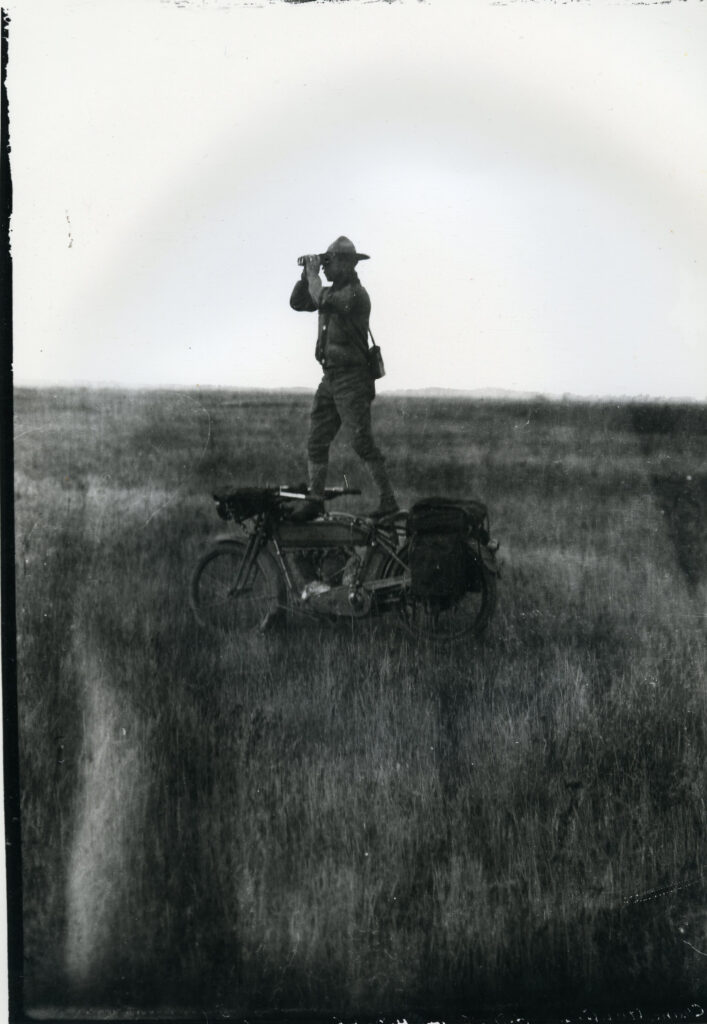

“Laing loved birds,” Trevor Marc Hughes says, “he got to know birds at a very early age, and he eventually saw the motorcycle as an ideal way to get out into nature because it was accessible and affordable. It wasn’t on rails, and it wasn’t the conglomeration of the automobile. He could just get out there, shut off the engine, and listen to the birds.” Laing was born in 1883 in Ontario, Canada but was raised on the family farm in southern Manitoba. He spent long days, essentially working as the ‘warden’ for the operation. Laing became a sharp marksman fending off natural predators with a rifle and learning to confidently recognize birds by sight and song. A teacher by 17, Laing taught at several area schools, and from 1908 to 1911, was principal of Oakwood Intermediate School. While teaching, he took a National Press Association correspondence course and wrote his first freelance story for the New York Tribune. In 1907, he bought a 4 x 5″ glass-plate Kodak camera to photograph wildlife.

After his epic 1915 cross-continental ride, Laing joined the Royal Flying Corps in Canada in 1917 to become a gunnery instructor. After the war he became a renowned naturalist, traveling the western and northern regions of Canada as a natural history specialist, working with the likes of the Smithsonian Institution and National Museum of Canada. He also sailed to Kamachatka and Japan on the HMCS Thiepval. His remarkable life was documented by B.C. historian Richard Mackie, who catalogued Laing’s papers after his death in 1982. Mackie’s book, Hamilton Mack Laing: Hunter-Naturalist was published in 1985. In that book, Mackie could only dedicate two paragraphs to the remarkable unpublished manuscript Laing had left behind.

In 2012 he rode another KLR 650 all over B.C. and wrote a book called Nearly 40 on the 37, a tale about the Stewart-Cassiar Highway, or Highway 37. He describes the road, the communities, and the people who live in the remote northern regions of the province – topics that don’t get much attention. Other B.C. travel adventures aboard motorcycles followed, and Trevor wrote another book, Zero Avenue to Peace Park. This is a tale of riding the highway that closely follows the 49th Parallel and the Canadian/American border.

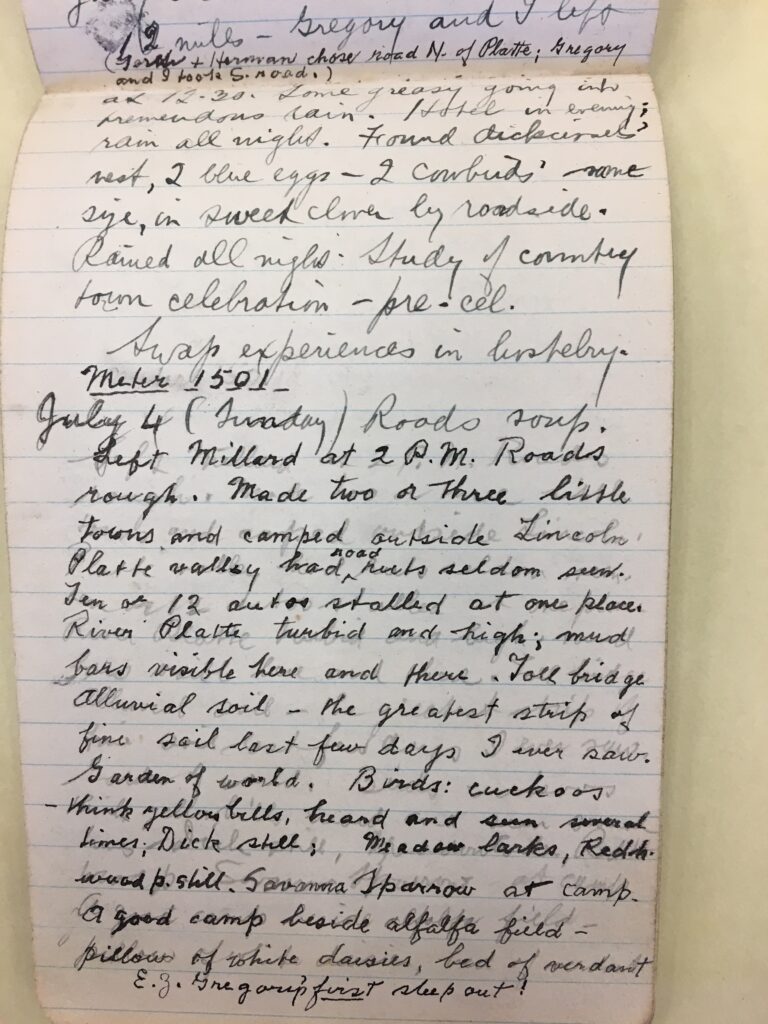

“First of all, I was overwhelmed by the sense of how long these pages had been in existence,” Trevor explains. “And then, holding the actual handwritten journals that Laing kept in his panniers while crossing the country – the feeling of the time it all comes from is quite special and it’s a very cool experience.” But technology has changed our lives, and using his iPhone, Trevor photographed every page of Laing’s manuscript. Returning home to his computer, Trevor began transcribing and editing Laing’s work. He sent pitches to a few publishers, and the first to respond favorably was Ron Hatch of B.C.’s Ronsdale Press, ‘a literary press specializing in Canadian poetry, fiction, belles lettres and children’s literature’. And now, a pioneering motorcyclist’s story of crossing North America in 1915.

In his book, Laing wrote of his 1915 Harley-Davidson, “We were off. I say ‘we’ for always I feel that the machine Betsy is more than an inanimate steed; rather a partner, a comrade of the Road, alive, and yet somehow, too, a part of me. I always address her in the feminine. In spite of her gruff voice she has very feminine traits. Anyway, it is far more poetical to call her Betsy than Bill. If she had not been christened Betsy then it must have been some other sweet and euphonious female name. I confess it came near being Growling Gertrude.”

“At Moline a brother rider picked me up and led me at a furious pace to Davenport. He was a road-burner, I was not. But as he had volunteered to pilot me out of the next city I tried to keep him in sight. He could not understand why I would wish to stop on the long bridge and take off my dusty cap in silent homage to the great Mississippi, the Father of Waters. To him I think this huge aorta of a vast continent was doubtless at its best but a muddy old river. For, with most of us, familiarity and contempt are two little sisters walking hand in hand.”

Laing rode for a short while in the Midwest with a motorcyclist he nicknamed Texas. On one of the roads they traveled, Laing recalled, “The running was much better that we spun along rapidly, and once I spun where I should not have. A little wet patch on the road scarce bigger than a tabletop was deemed too insignificant to be worth dodging, although Texas who was leading deemed it so, and I picked myself up from the side of the grade where Betsy prone on her side had dug a furrow with her foot-boards and her face. That mud patch was alkali! My comrade ahead heard the rumpus and came back, and after we got Betsy on her feet and the half-dried mud detached from parts of her, also got the handlebars straightened, she was ready again. But she had a new dreadful appearance. There was not more than a square inch of glass in the lamp and it was knocked awry and jammed and battered shockingly. Texas who was an authority on cyclones said we had the appearance of having weathered a good one.”

Related Posts

February 14, 2018

The Vintagent Selects: Josh Kurpius DKS! Harley Davidson Ambassador

DKS! went to Milwaukee, WI. to meet up…

I always enjoy reading your articles Greg. This one left me torn wondering if time permitted would I chose to trek to great places and just stop to take it in or head to Vancouver Island to try and find Barking Betsy. What a restoration project that would be!

In your capable hands, Matt, you could pull off both — the meditative experience and a terrific restoration should those bones be found! Cheers for the support.