By Scott Rook

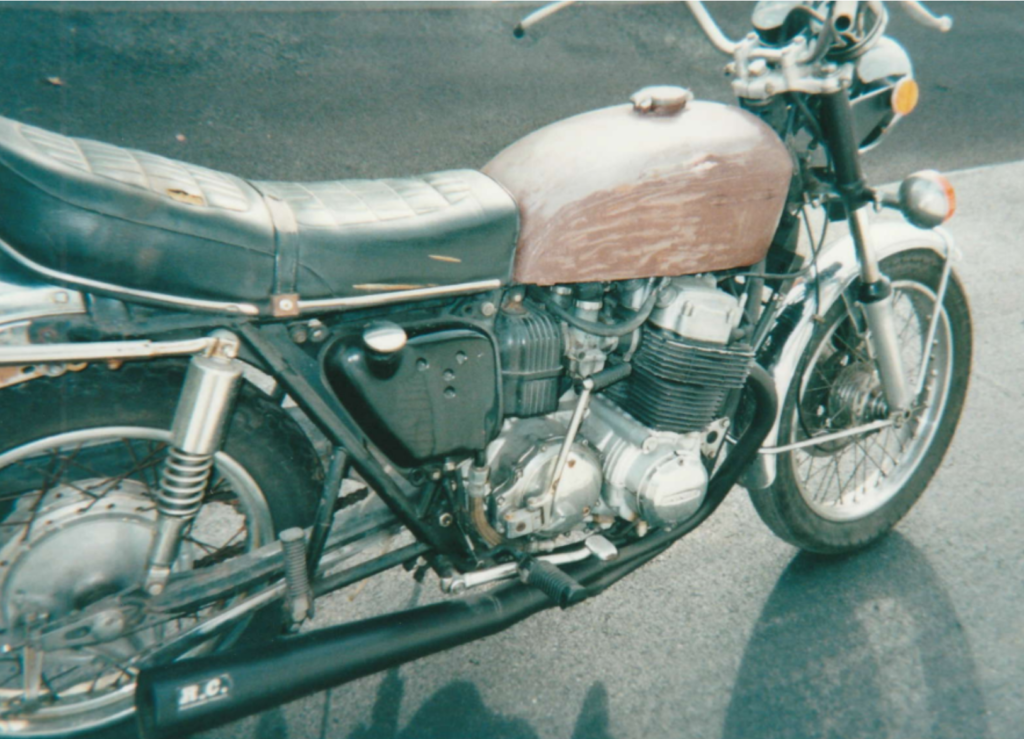

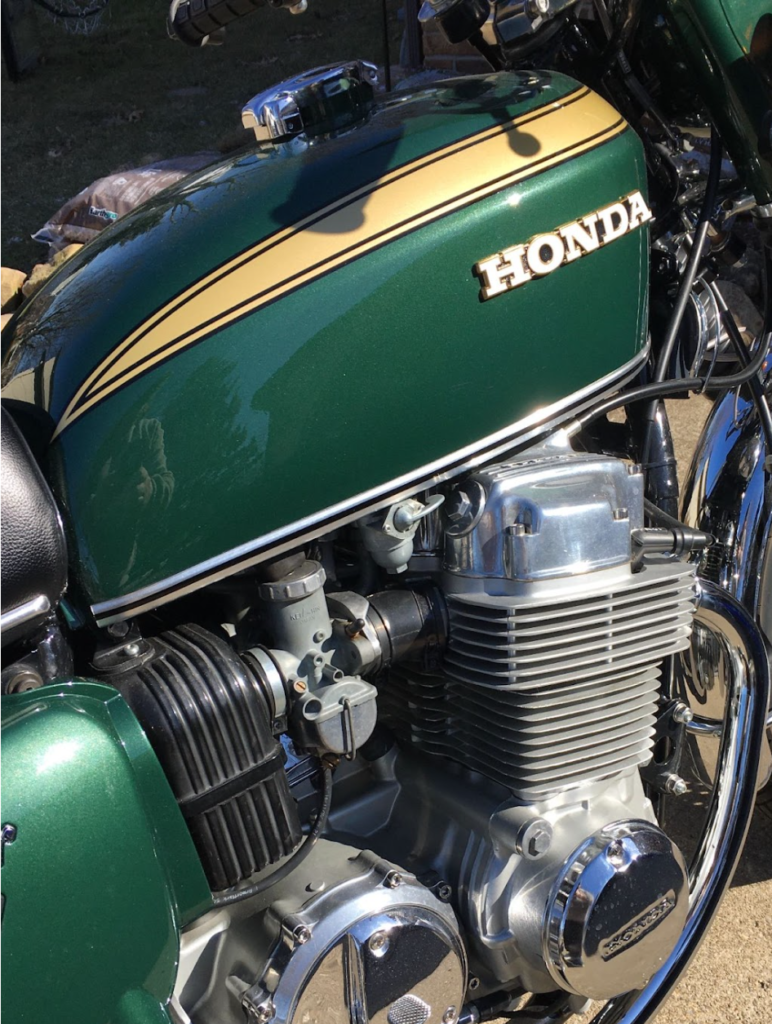

Being a child of the 1980s, I never knew a time when fast bikes on the showroom floor didn’t mimic the factory’s race bikes. Kawasaki had the Ninja and Honda had the Hurricane. [Shameless plug: read our history of the cafe racer, ‘Ton Up!’] The bikes appeared on magazine covers in the school library that all my friends drooled over in study hall. When I got interested in vintage bikes in the 1990s, the idea of an old street bike that was kitted out in race trim took hold: a cafe racer. The Honda CR750 was the bike that did it for me. Cycle World ran a story about Dick Mann and his Daytona-winning Honda CR750 from 1970: someone built a replica and was racing it at Daytona in the AHRMA series. The factory CR750 racer looked nothing like the old CB750 that I’d owned. The Honda had been replaced by a 1979 Triumph Bonneville, but when I saw the CR750 in the magazine I thought, I could build that and ride it on the street. After all it was just a CB750 underneath that root beer colored fairing, and CB750s could be found cheap in the early 1990s. This was my cafe racer dream. I started making spreadsheets of parts and searching the internet with my dial-up Internet connection. I perused the newspaper looking for any old cheap CB750. I found one; a non-running K1 for $250. My girlfriend (who would later become my wife) went with me to check it out. We stopped at U-Haul on the way and picked up a motorcycle trailer just in case. The bike was rough. The cases were cracked but most of it was there, and it had a title. The 1971 CB750 came home with me that day and has been with me ever since.

I had loved the process of building my Dunstall Honda: it was full of the anticipation of riding a bike that belonged in a different era. The Dunstall Honda was something different, like a lost treasure that the world had forgotten. And I brought my cafe racer dream to life in my garage. The realization was exhilarating, but the ride was terrible. I remembered my old CB750 and how it did literally everything: I rode it on grass while learning to ride a motorcycle, I rode it to school and took it on camping trips with my friend on the back. That old CB750 took me and my high school girlfriend everywhere. The Dunstall Honda did nothing well other than go fast and look great. I couldn’t take it anywhere without experiencing pain. Maybe that is how beautiful strange things from a different era are supposed to be. They have to extract a toll from their owners for their existence. Not just a financial cost, but actual pain when used as intended. I wanted to like riding the bike, and gave it my best, but never really enjoyed it. So I changed clip-ons and played with different hand grips, and tried to make it even more cafe racer by adding a boxed swingarm and rear Hurst Airheart disk brake conversion. I changed the wheels to the even more rare Henry Abe mags, all in an effort to love the bike I had built. None of it worked. I rode the bike once or twice a summer for many years. I polished the aluminum covers and waxed it. I kept it in tip top running condition hoping that someday I would love riding it. But that never happened. The cafe racer dream had become a painful nightmare.

I still have a cafe racer dream, but it doesn’t involve Dick Mann or clip-ons. I want to build a bike that has the cafe racer look but keeps the standard riding position. Paul Dunstall built Sprint versions of his Norton Atlases and Commandos. These were bikes with performance upgrades and the cafe tank and seat but with regular bars and pegs. A bright red Dunstall Domiracer Sprint sounds about perfect for me. I guess I have a new cafe racer dream. Stay tuned.

As we’ve read then and since, Dick Mann won the Daytona 200 on his “factory” kitted CB750, March 1970 and I was 20. By July I’d sold my red Super Hawk to my brother and bought a candy red stocker and within a couple of weeks left on a ride from Wooster, Ohio to Los Angeles then up the coast. (My buddy Bob rode a CL72 with a CB450 engine installed.) By Autumn 1970 I was running typical clip-ons; simple, non-adjustable. Studying Industrial Design at OU, I built a decked solo seat mimicking the Rickman brothers better early work. Bob made me rear sets. I rode that bike until I stuffed it into the side of a Datsun 240Z, then bought a new 1972 and moved the components to that CB750 and added a replica of Mann’s full road race fairing, headlight fitted. Sure, I was profiling a bit, but I loved that riding position. Thankfully the greater industry, with an eye firmly focused on Ducati’s offerings mid-1970s, started to make “sport bikes” around 1982 and bikes like the VF750F came to my garage, then a ’93 ZX750, then a ’95 916 Ducati which rivaled the good old Honda 750 for riding position. All were a bit lighter, much more developed and focused than the old Honda Four.

Neither 50 years ago or now would I write off the cafe racer, or full tilt sport bike, like a 1985 GSXR750 or 916. All my buddies rode this stuff, did a bit of amateur road racing. The riding position gives the rider ultimate control at speed and is OK around town, not where you want to be anyway. Maybe you’ll experience a little forearm pump, but one ibuprofen before heading out for a long ride cures that. Cafe racers, and the modern form, the sport bike are at my core, in my blood, the highest form of street bike.

I’ve never owned an uncomfortable cafe racer, but I’ve ridden some! Actually the worst for me was the ’74 Ducati 750 Sport – the stretch over that lovely long gas tank was murder on the lower back. But, I had a cafe racer ’74 Ducati 750GT, with clip-ons and rearsets but the original short GT tank, which was perfectly comfortable. I sold it as I actually found riding a hot ‘standard’ 750GT with handlebars easier to hustle around our local mountain roads than the cafe racer with clip-ons: in other words, I rode wicked fast on an upright bike, as the leverage was much better for cornering. A lot of early Battle of the Twins racers discovered the same thing, until they were barred from using handlebars as it didn’t ‘look right’ for BoTT. The AMA didn’t want the flat track guys to come and mop up the track on tight courses…

I still have my ’66 Velocette Thruxton, but it’s the only cafe racer left in my stable. All the rest are actual vintage road racers, desert racers, and a Brough Superior.

Going through both Craigs list and Facebook Marketplace, you are likely to see many bikes “cafe racerized” with nothing more done than parts taken off and a hard, flat seat replacing the original seat. These things do not a cafe racer make. Put some thought into it, buy a few aftermarket parts but most importantly, make the bike personal to yourself. You are doing something for yourself and you better like what you do or it’s nothing.

One more thought…..and that is, a cafe racer is a road racer, a competition bike, with lights. That’s what all the Limeys were really after when they invented the things. Per John, above, removing fenders and installing a minimal seat and impossibly big knobby tires ain’t…..

When I was about 18 and modified my Super Hawk, I wanted the riding position and the look, I’ll admit (flat bars, stock on early Hawks) open megs (Factory CYB parts) a long tank (moulded in CB450) and a solo decked seat (hand made). Rear-sets are stock on Super Hawks.

But when I think of the real mission here, it’s to have a true full tilt road racer in the form of a Manx Norton (or a stripped Thruxton) with what the law requires to be on the street; lights, horn, mirrors, etc. Comfort and fouled plugs be damned. Riding my Hawk flat out, well tuned, rider completely tucked in, possible tail wind…well…my speedo read (an optimistic)105mph.

As I point out in my book ‘Ton Up!’, the cafe racer wasn’t invented in the 50s, it goes way back, maybe before motorcycles, to the human urge to go fast, and its corrollary, looking like you’re going fast. I found the origin of the term ‘Promenade Percy’ in 1930, which was the British precursor to the Ton Up Boys: riders who liked flashy fast bikes. In the 1920s Phil Irving documented how he was an OG cafe racer lad, painting his tuned AJS single purple, and running illegally with a straight pipe, no lights, and a borrowed license plate. Nothing is new…

I remember trying a brand new 750after a 500 km checkup, i don’t like it: very heavy on the front,

and an unpleasant handling. The 500 wasn’t a Chopin, but was more homogeneous with the weight at the right place

and it was easy to work on them, as the 750 needed to pull out the engine only tho re tighten the head.

Like Paul, my favourite is a Venom Thruxtonised by two Veloce factory triers , fast and light.

The only Honda who impressed me was the VF 750…and her unbreakable engine.