Osa-san’s Sense of Ride

After World War II, life in Japan changed dramatically. The country was physically devastated, occupied by the US military until 1952, forced to abandon its previous Imperial form of government, and forbidden from rebuilding certain industries previously associated with the war machine – notably aviation. Many industries that had supplied the military since the mid-1930s scrambled to find new uses for their manufacturing know-how, and re-tooled for new options like providing inexpensive transportation, especially motorcycle production for urban transport. During the 1950s, Japan experienced a dramatic surge in motorcycle production that progressed from a small, domestic industry into a global leader. This growth was fueled by the country’s post-war economic recovery, foreign and domestic investment through government loans, allied with an explosion of demand for affordable transportation. Initially, hundreds of small companies entered the motorcycle market, but according to the book Japan’s Motorcycle Wars, the dominant brands had previous experience mass-producing engineered items for the Japanese military, and were already big companies.

[1] The Global Impact of Japanese motorcycle manufacturers, Francis Rozange, 2024.

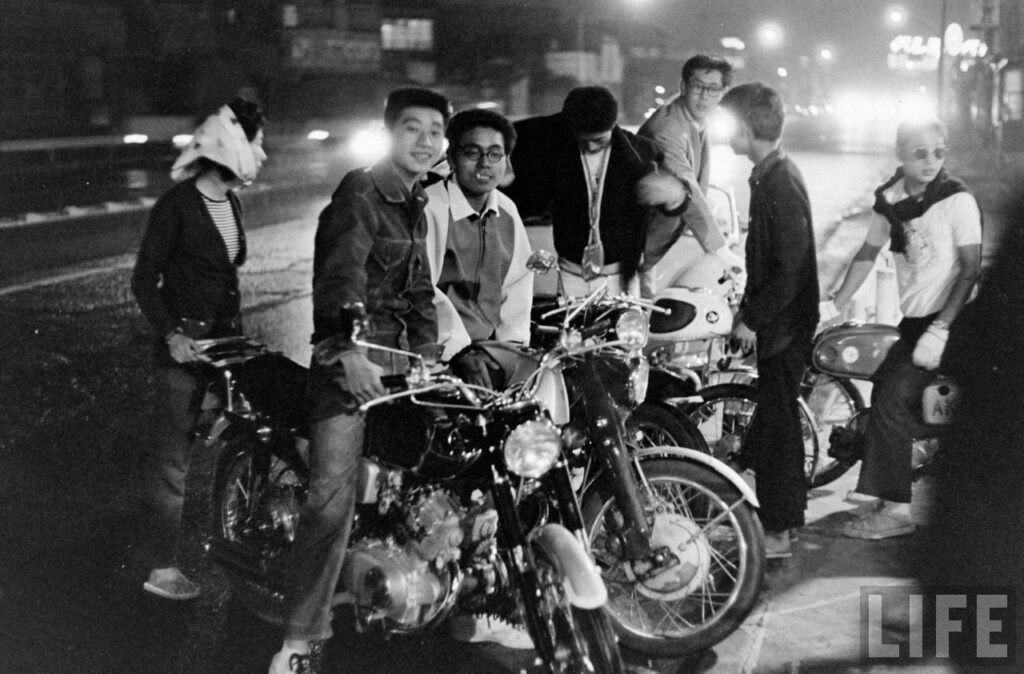

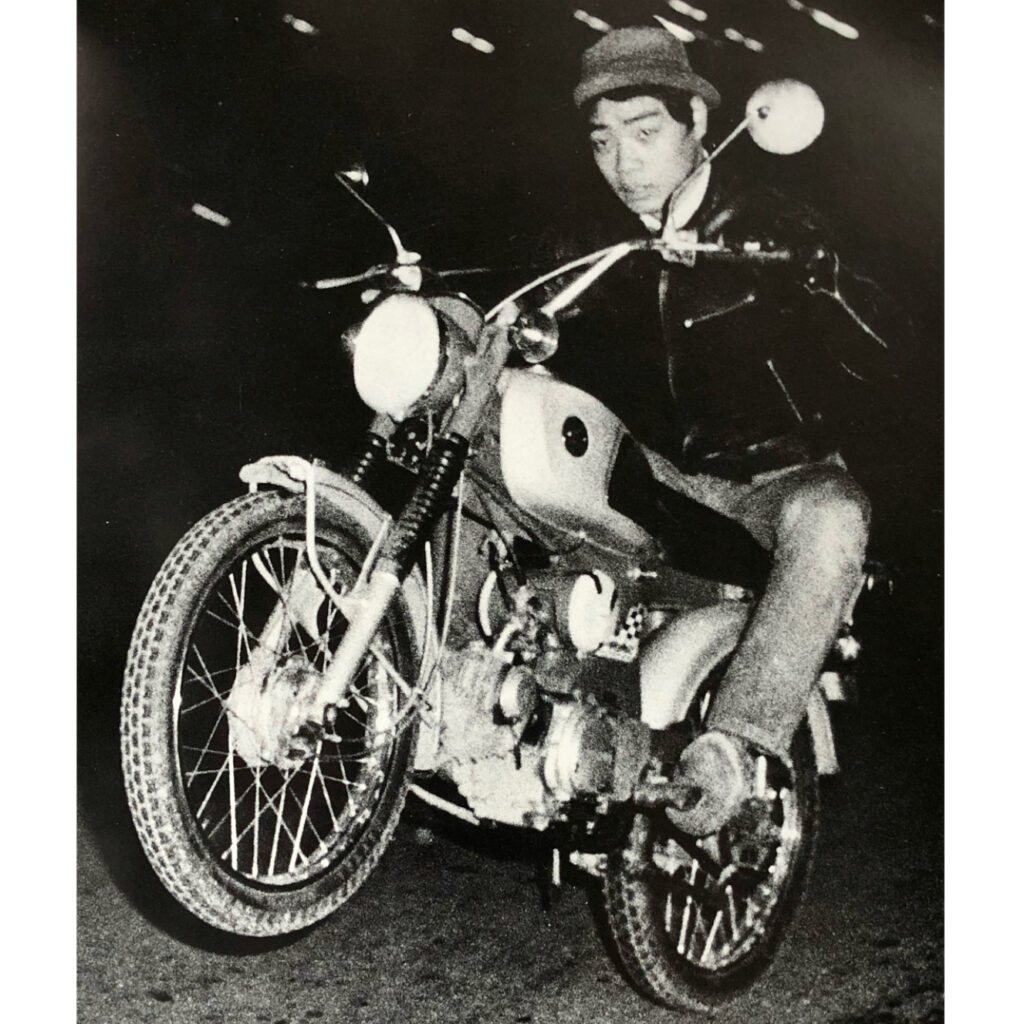

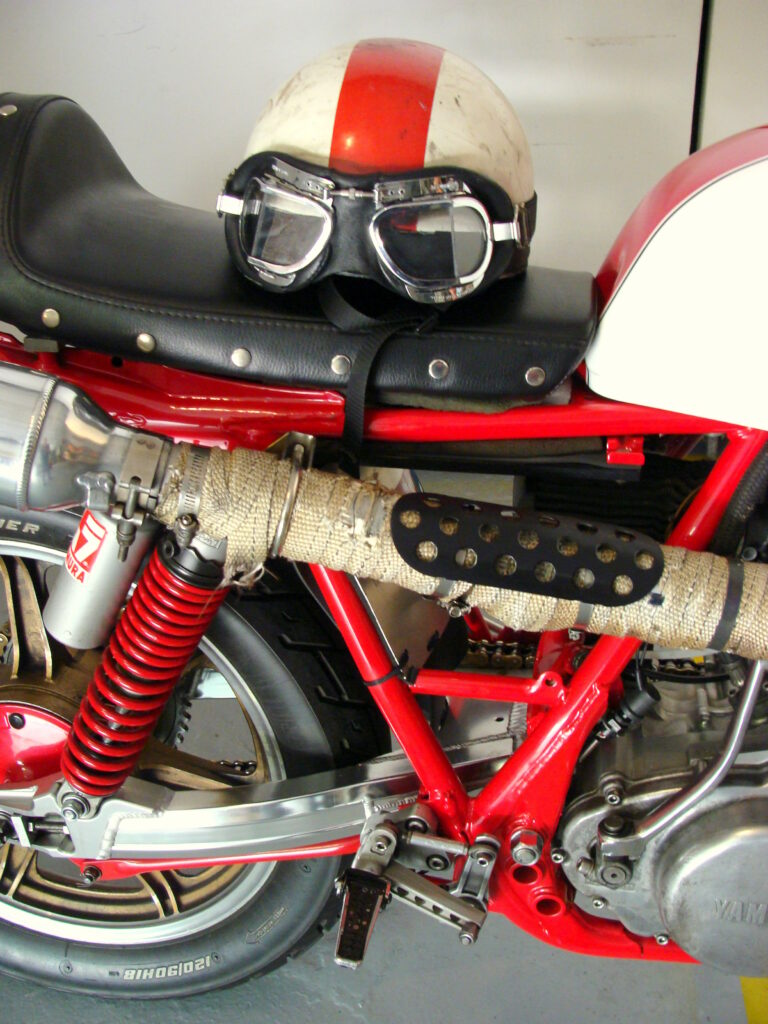

[2] Bōsōzoku (暴走族, lit. ’Reckless driving group’) is a Japanese youth subculture associated with customized motorcycles. The first appearance of these types of biker gangs was in the 1950s. Popularity peaked at an estimated 42,510 members in 1982. Their numbers dropped dramatically in the 2000s, with fewer than 7,297 members in 2012.

[1] Later, in 2020, a Bōsōzoku rally that used to attract thousands of members only had 53 members, with police stating that it was a long time since they had to round up that many people. (from Wikipedia)

This…. is total BS !

First off .. the Bosozoku up and until their demise was from day one a feeding ground for the Yakuza . With the Yakuza using them to do their dirty work while hiding behind silk screens .. till someone proved themselves worthy ( because Yakuza IS family based ) and was elevated to Yakuza status .. albeit at its lowest ranks

Second .. there is no more Bosozoku in Japan . They are gone .. poof … no more …Japanese authorities made damn sure of that .. replaced by a few midnight maniacs on fast bikes who occasionally travel in groups … one or two of whom still pretend to be Bosozoku .. though the Yakuza no longer recognizes them as such .

Third .. in light of who the Bosozoku were .. and what they stood for … saying there is anything so much a s resembling Bosozoku in NYC is complete and utter BS .

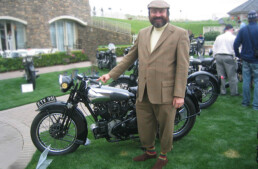

Oh sure .. like our Suburban Urban Hipster Wanna Be’s pulling around on old H-D choppers / bobbers pretending to be 1%ers … I’m sure there’s a few idiots like Osa – San doing the same with Bosozoku style … pretending they really are . When in reality they like their Tighty Whitey Suburban Urban Hipster Wanna Be’s … are just a bunch of fakes on M/C’s desperately seeking meaning in their vapid little lives begging for attention at every corner of the net and beyond

For an ACCURATE history of Bosozoku … both NHK ( Japanese news ) and VICE have lengthy ( VICE has at least three ) videos on the actual history of Bosozuko .. from origin to their ultimate demise

Seriously PdO and Co. .. there’s enough BS , fake news and revisionist history out there .. and we certainly don’t need any more … so for the love of Motorcycling .. cut it the hell out …