Phil Irving's 'Other' Twin: the Velocette Model O

By Dennis Quinlan

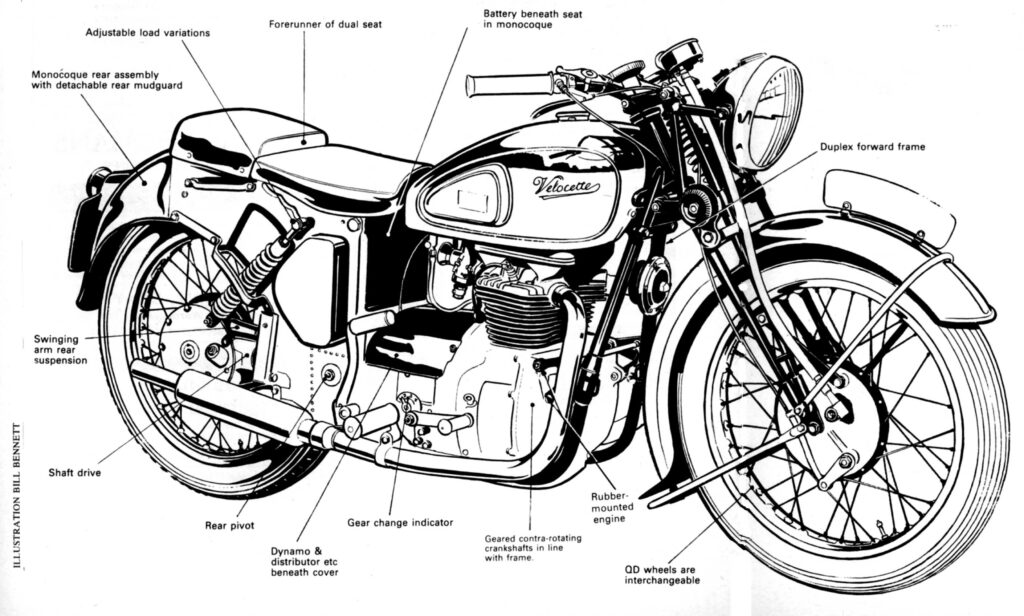

The legendary Australian engineer Phil Irving, or “P.E.I.” to fans, is best known for his design work in collaboration with Philip Vincent to create the immortal Vincent V-twins in the 1930s and 40s. Less well known is his work at the Velocette factory to develop new designs during the tumult of the 1930s. Irving in fact worked twice at Veloce Ltd in the period 1930-1942, where he assisted in design and alterations to existing models in the Velocette range (the ‘K’ overhead-camshaft and ‘M’ pushrod series machines). This work was augmented in 1938, when he was given the brief to design a road-going version of Veloce’s new 500cc twin-cylinder supercharged racer, called “The Roarer” by factory development engineer Harold Willis. The Roarer was developed by Veloce designer Charles Udall, who did his best to ready the new design for the 1939 IOM Senior TT, and while the racer was tested by Stanley Woods at the TT, it did not compete as certain issues [ie, glowing red-hot spark plugs - ed.] had not yet been resolved.

The engine would start at “the brush of a carpet slipper”...!

It was not quite so with the Model O, but two or three kicks saw me ride off to catch up with the others. The seat height is a little on the low side when compared to the many Velocettes I’ve owned. When I took off it was smooth, though the steering seemed a little heavy in comparison to the light and nimble TT winner I’d been on, and if you've ever ridden a 1920s Velocette, you'll understand. The heavier steering came to prominence on the first left-hander I rushed into, and I thought - crikey don’t fall off! Acceleration was “adequate”… I wasn’t about to thrash it and the gearbox had a BMW feel as the Model O gearbox similarly runs at engine speed, but with a multi-plate clutch, the gearchange wasn’t clunky. The brakes were good and in no time I’d settled into the ride, ending up too soon back at Ivan’s, where I let the machine idle to muse at my good fortune and pleasure of riding such a special machine.

Summarising: the thrill of riding a one-off prototype is something I’ll remember into my dotage.

The Mysterious 'Mark 6'

[Words: Dennis Quinlan and Paul d'Orléans]

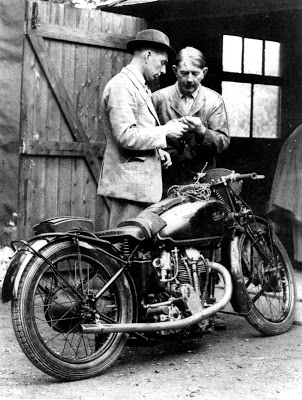

The Veloce factory built motorcycles from 1905, but their first models of inlet-over-exhaust engine construction were typical for the day, and produced in very small numbers. In 1913 they designed a 220cc two-stroke single of rare quality, called the Velocette, which the factory developed continuously through 1946! Veloce leaped to the forefront of motorcycle technology in 1925, introducing an overhead-camshaft (OHC) single-cylinder Model K, a 35occ machine of peerless handling and excellent performance. A factory-tuned Model K racer won the 1926 Isle of Man TT, which created huge demand for the roadster model. In 1928 another racing K took the one-hour speed record over the 'ton' at the Montlhéry Autodrome, with a 100.3mph average speed; this effort would be multiplied by 24 in 1960, when their pushrod Venom 500cc model took the 'ton for a day', also at Montlhéry.

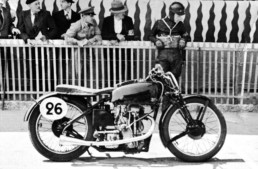

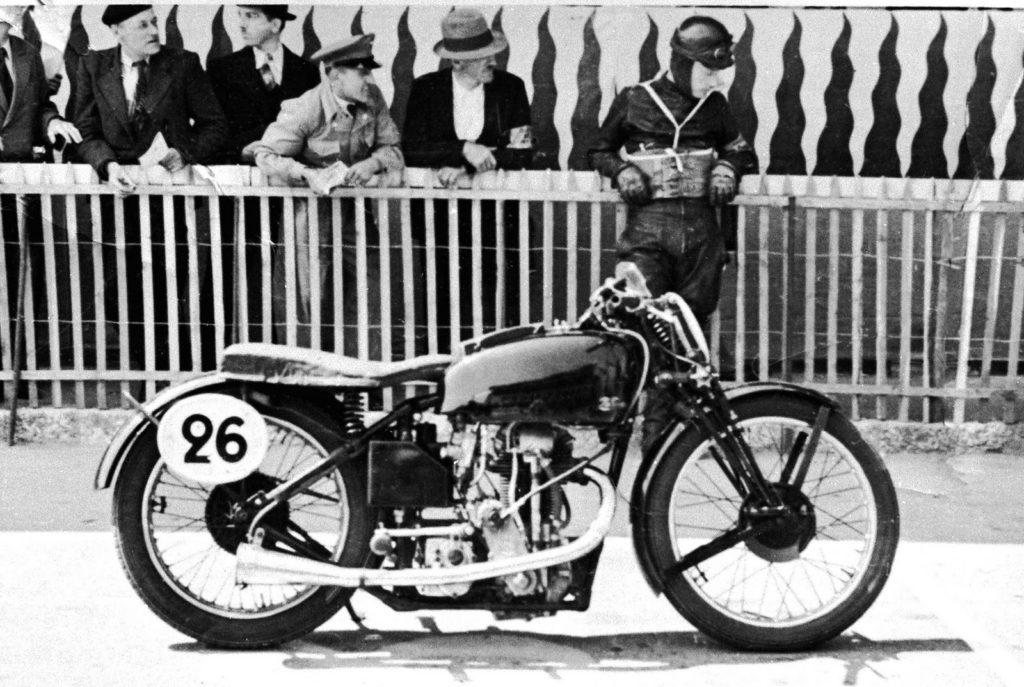

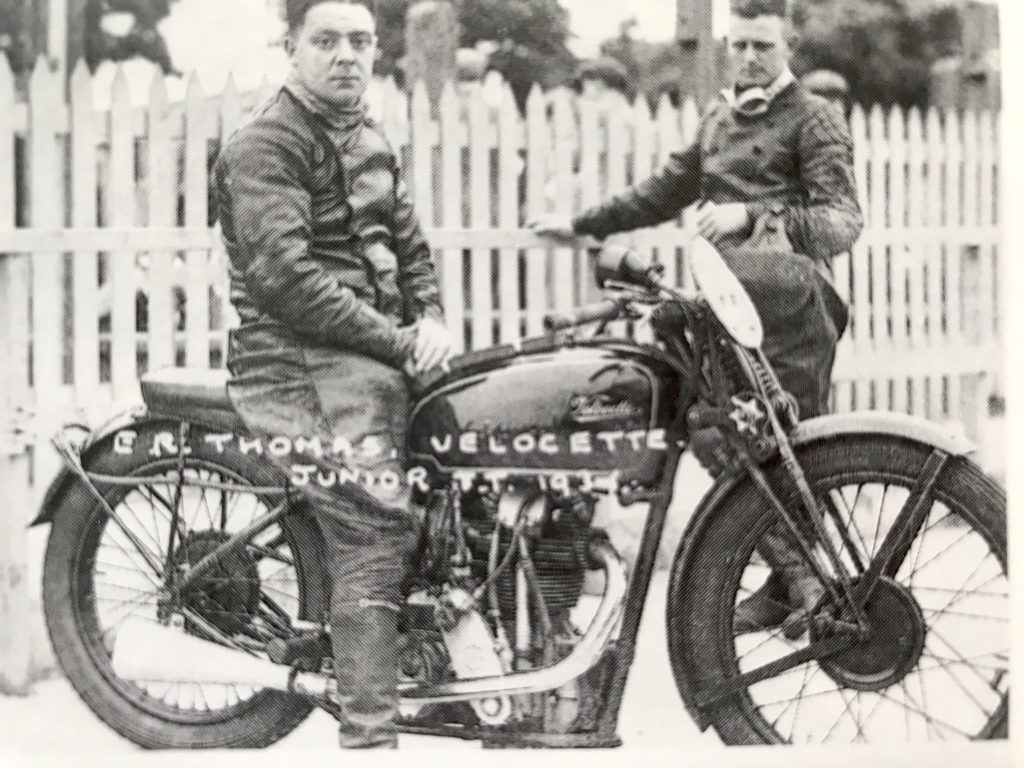

Veloce made a series of TT Replicas between 1928 to 1951, production racers that were copies of their successful factory machines that were busy winning TTs and GPs around the world - the Velocette KTT models. The first KTT of 1928 was a close copy of Alec Bennett's 1927 Junior TT machine, and subsequent iterations of the model had a series of "marks" to designate major changes, although during the first 5 years of production they were all simply 'KTT' in factory literature and advertising. The first catalogued change to the line appeared in 1932, with the 'Mk4' KTT for 1933/4 seasons; thus the earlier machines were retroactively 'Marked' 1 thru 3. The KTT had major changes on each model from 1934 onward; the Mk5 (1935) had a new frame and bronze cylinder head, the Mk7 (1937) had a completely new all-alloy engine and new frame, and the final version, the Mk8 (1938-51) had the Velocette invention of a swing-arm rear end with two suspension units - a setup recognizable to any motorcyclist today.

But there's a 'missing' KTT - the Mk6, which was never advertised and never appeared in the factory literature. Did Veloce simply skipped over the number 6? Like the Loch Ness Monster, rumors have swirled since 1936 regarding the existence of a Mk6 KTT. Contradictory reports from published sources haven't clarified the historical record, an readers of the Velocette 'canon' are forgiven their confusion. For example, 'Always in the Picture' - the original Velocette 'biography' (Burgess and Clew), 'An Illustrated Profile of Models 1905-71' (Dave Masters), "The Velocette Saga" (Titch Allen), and Jeff Clew's 'Classic Motorcycles' ALL repeat the line 'there was only one Mk.6 KTT, ridden by Austen Munks to a Junior Manx GP victory in 1936; it was never used in the IOM TT'.

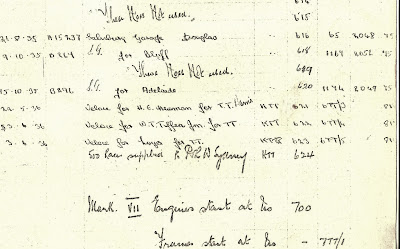

All of the individuals involved with the 1930s Veloce race team are now dead, but with photographic research, race entries, and clues from the Works records, we can ferret out the story of this elusive beast. And from all this, we can conclude that there was not one but three Mk.6 KTTs, all ridden in the 1936 Isle of Man Junior TT. It's reasonable to assume these were the prototype for the Mk.6 KTT model, as production of the Mk.5 KTT finished in October 1935 with engine number KTT620. The factory records show a gap of 17 months before the first Mk.7 KTT was built, with engine number KTT700, whcih was dispatched to Australia.

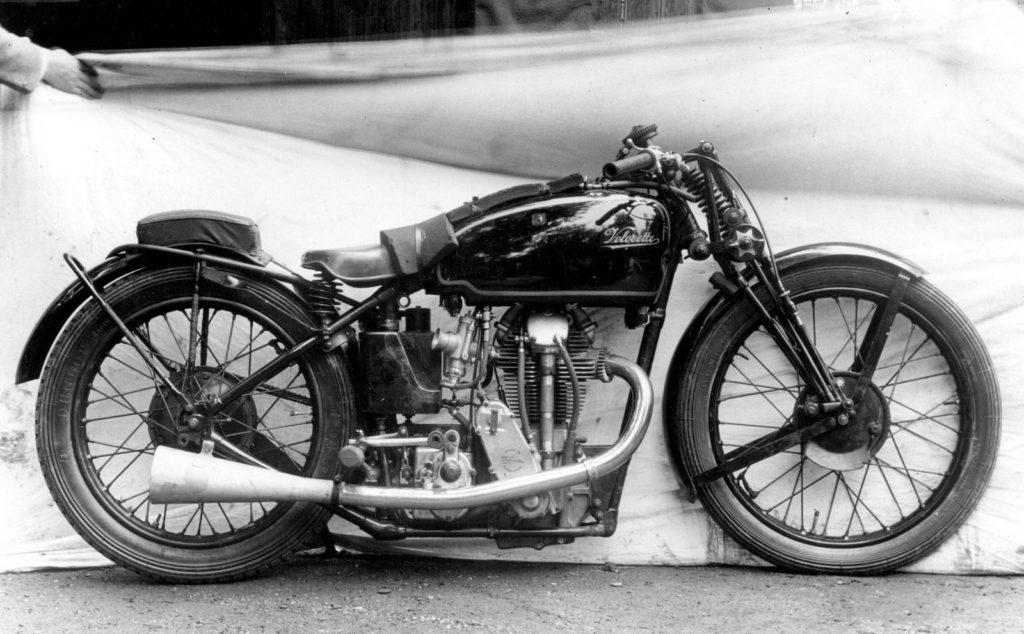

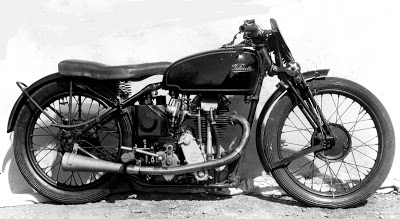

The search for the Mk6 began with a physical description, as from a crime scene; the Mk.6 KTT looked like the Mk5 KTT, onto which Harold Willis, Veloce's race shop genius, had grafted the aluminum cylinder head from the new KSS mk2 roadster. Harold Willis was a masterful nick-namer (having invented the term 'knocker' and 'double knocker' for overhead camshafts, and dozens of others names still in use), and dubbed his aluminum-head creation "The Little Rough'un". Another useful snippet of information appears in Les Higgins' delightful book 'Private Owner', about his years racing Velocettes. Describing his racing in 1936, Higgins says (p.41): "another machine was difficult to come by, because Veloce Ltd. had temporarily ceased manufacture of the KTT model. The last machine made in any quantity were the Mk.5 models. A few Mk.6 machines went out to approved customers and the concern was now busy evolving something new to provide an answer to the International Norton".

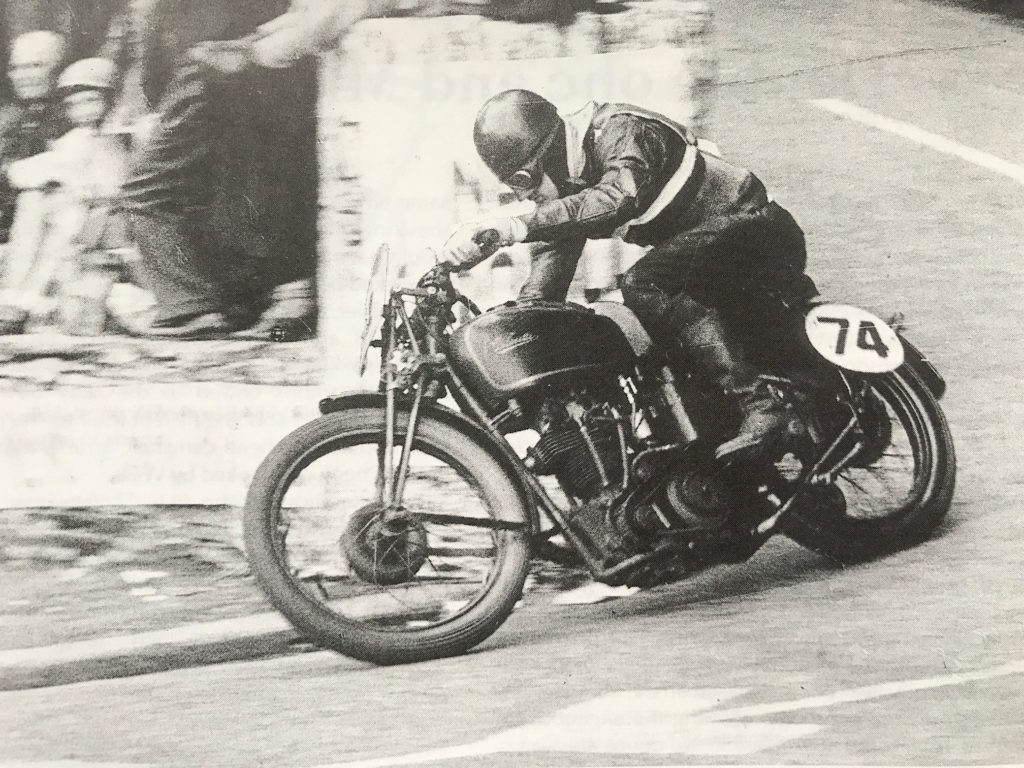

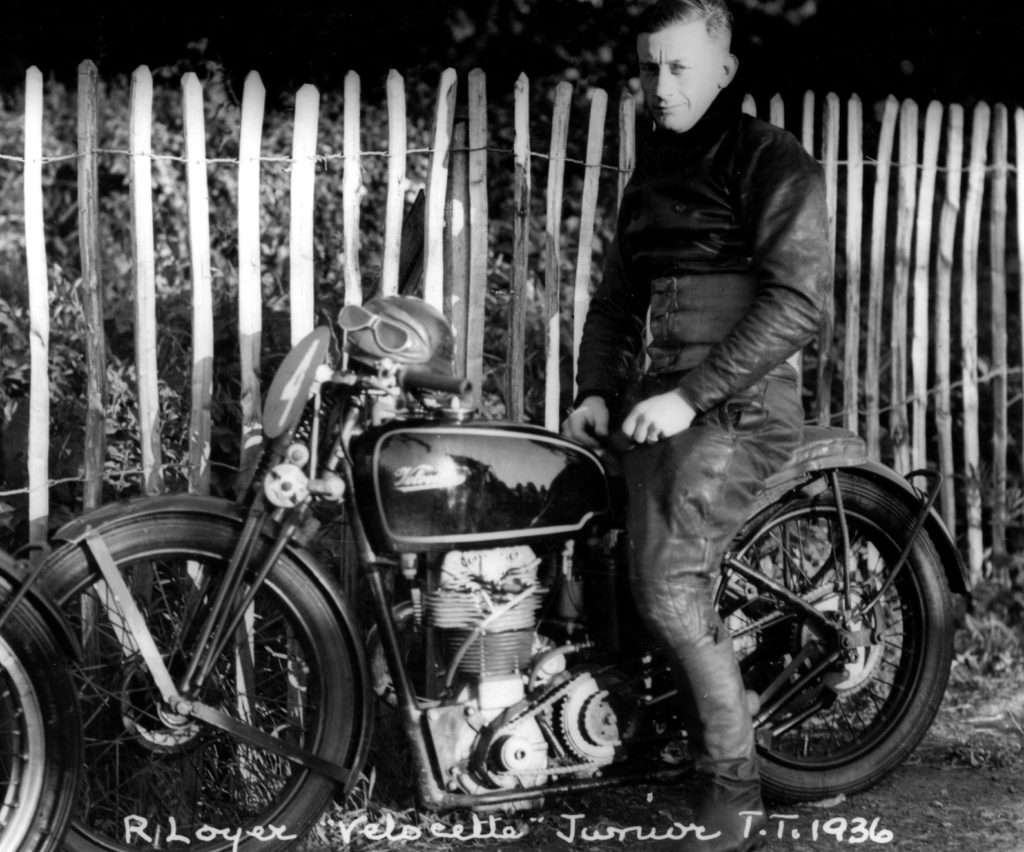

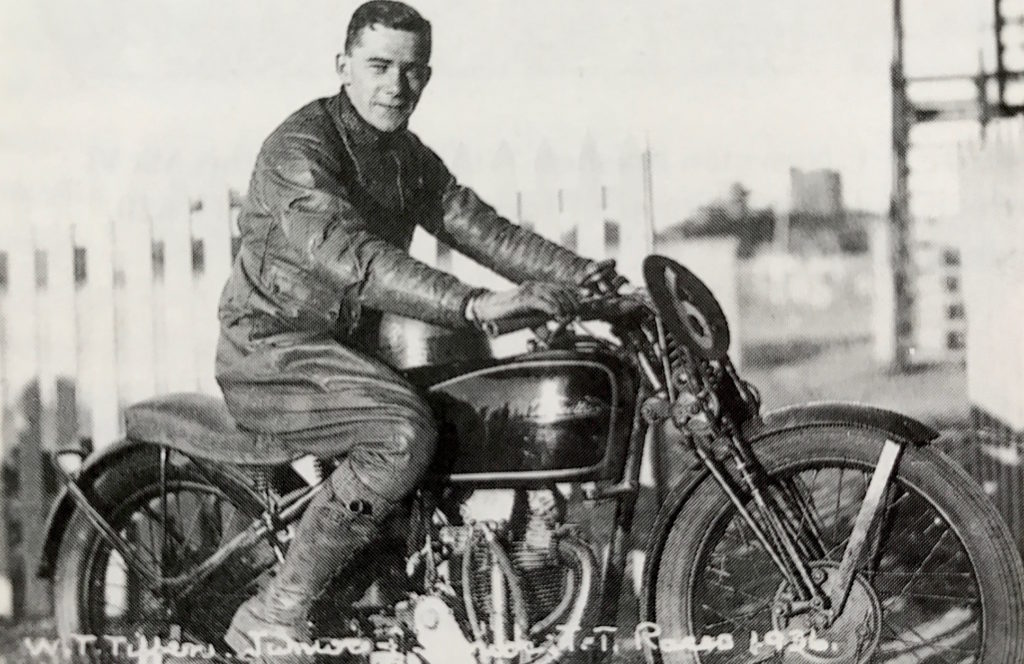

The 'approved customers' of the three Mk.6 KTTs at the Isle of Man in 1936 were H.E. Newman, Billy Tiffen and Roger Loyer. Photos from 1937 show Ernie Thomas, Les Archer and his son, and one unidentified rider, all circa June 1937; because of the date these are likely from the '37 IoM TT races. An extract (below) from the Velocette factory KTT records gives the following notations: June 1936: Veloce for H.E. Newman for TT - engine #KTT621, frame 6TT3. June 1936: Veloce for W.T.Tiffen Jnr for TT - engine #KTT622, frame 6TT4. June 1936: Veloce for Loyer for TT - engine #KTT623, frame 6TT5.

The reference "Veloce for TT" is used in the factory records to indicate a special Works-prepared racer, tuned in the factory race shop for designated riders, as opposed to the standard KTTs offered to the general public. Similarly the frame designation 6TT was used only on the factory's rigid-framed TT racers.

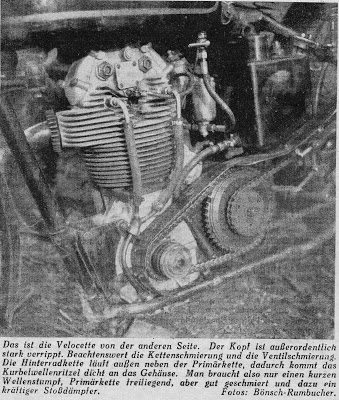

Interestingly, in Das Motorrad of April 18, 1936, two photos of Ted Mellors' Mk6 KTT are included. The engine number is obscured, but the publication date of the magazine pre-dates the mk6 factory notations above. Mellors was occasionally engaged by Veloce to race their motorcycles, and the machine in these photos certainly looks like a factory racer, as the bevel box drain is not the same as a KSS Mk2. The mystery deepens...

Could this have been the first testbed of the new cylinder head? The weekly motorcycle paper "MotorCycling" of June 17, 1936, in the "Straight from the Island" article, included this interesting snippet, previously overlooked by historians: "One or two of the lads who are riding Velocettes, notably H.E Newman, will be mounted on advance KTT jobs for 1937. These are standard products, but they can motor very rapidly".

How did they fare in the TT itself? Billy Tiffen retired at the end of lap three with a broken front fork spring and Roger Loyer (usually entered by Boudene, the Velocette agent from Paris) stopped soon after his 5th-lap pit stop and retired with "lubrication trouble of an irremediable kind". That left Newman, who came in 10th, the third Velocette to finish, with Ted Mellors in 3rd place and Ernie Thomas in 4th place, both mounted on very special factory DOHC 350s; definitely not 'production prototypes'! Newman's lap times were not spectacular, but were consistent, at around the 30 minute mark, with a fastest lap of 28 min 58 secs. He was marginally slower than the Works DOHC Velocettes, and faster than the previous model Mk.5 KTTs, as ridden by Noel Pope, Gledhill and Chas. Goldberg from New Zealand.

Development of the Mk6 seemed to continue, as a photo of Ernie Thomas mounted on a Mk.6 KTT in the 1937 Junior IOM TT seems to be Newman's 1936 machine, now with a different type of seat. And as mentioned, the Archers, well-known Velocette agents, also rode a Mk.6 KTT in the 1937 TT. Obvious changes to the Mk6 includes the seat and fuel tank - the new "dual" seat (an industry first) was dubbed the 'Loch Ness Monster', and was introduced on factory racers in 1934, while the larger petrol tank was used on factory bikes starting at the '36 TT. The rear wheel of Archer's Mk.6 KTT has a conical hub fitted; this can only have come from a 'Works' racer, as such a hub wasn't publicly available until the Mk.8 KTT appeared in April 1939.

With reasonable results in the TT, why didn't the Mk.6 continue into full production? Perhaps with the introduction of the massive square-finned alloy SOHC engine ( 10" x 10") to the factory bikes, and the subsequent improvement of lap times, Harold Willis felt this new all-alloy racing engine was the future. Stanley Woods was lapping over 1min.17secs. a lap faster than Ernie Thomas in the 1937 Junior TT, despite the development time spent on the Mk.6 during the intervening year - Thomas's best time was only marginally better than Newman's the year before. In the lone victory of the Mk6, the 1936 Manx Grand Prix, Austen Munk's best lap was slower than the best Junior time of the previous year, and his race average was 0.1mph faster than Newman's '36 TT time.

Why was the Mk6 so much slower than the Works bikes? A more detailed review of factory literature reveals a few drawings of parts for the Mk6 KTT: drawing KO2716 (part no. K27/16), is the piston, described on the drawing as for the KTT Mk.6; drawing KO2805 (part no. K28/5) is the connecting rod for the KTT Mk.6. Both give clues to the engine's weak points. Inspection of a piston from a Mk.8 KTT (part no.K27/16) reveals it to be identical with the Mk6 piston drawing. A hard look at period photographs reveals the cylinder barrel of the Mk.6 KTT is the same alloy barrel of the Mk.7 and Mk.8 KTTs, making the Mk.6 in effect a Mk.7 engine type, but with a KSS Mk.2 cylinder head fitted. After testing in the TT and Manx GP in 1936 and 1937, plus a few Continental GPs (according to the late Bruce McNair's conversations with Roger Loyer), the Mk.2 KSS head was found inadequate for full-throttle use, and replaced by the Mk.7/8 type with larger finning. These cylinder heads were nearly the same as the 'Works' 1937 cylinder heads, although only 9" x 9" square; the resultant machine was then offered to the public as the 'Mk.7' in 1938.

What was the problem of the KSS Mk2 cylinder head? The combustion chamber shape of the KSS head is virtually identical with the Mk.7 KTT head; the valve sizes are the same, but the inlet tract is a bit larger. Perhaps there was trouble with the coil valve springs inside the enclosed Mk.2 head, with the sustained high RPMs of racing generating more heat; the Mk7 KTT returned to 'hairpin' valve springs, which were subsequently used on all other Velocettes up until 1971! Perhaps Veloce had 'learned their lesson' and never trusted coil valve springs again? The relatively scanty finning on the Mk.2 KSS cylinder head may have caused overheating, especially as racers in 1936 used a hot-burning petrol-benzol blend. Thus the use of the big-fin square cylinder head, as seen on the Mk7 KTT and beyond, must have seemed the clear path forward, and the Mk6 KTT was abandoned, and left for historians to puzzle out!

Thanks to Dennis Quinlan for his exhaustive primary research!

Velocettes in Antarctica!

I guess it would be impossible today... taking any motorcycle to the Antarctic, let alone an old one with oil leaks. But, it has been done! Not once, but twice with Velocettes, in 1961 and '68 (there have been other motorcycles on the continent, notably Benko Pulko in '77 and David McGonigal, both on round-the-world oddyseys). The Velos were brought by two Australians; Bill Kellas in '61 and Frank Scaysbrook in '68, who were both on one-year postings at the Australian research base at Mawson, in Wilkes Land, Australian Antarctic Territory (see photo of Frank with his MAC 350cc, Adelie penguin in his lap, and a curious Husky, at Mawson base, 1968).

In January 1961, the Danish polar vessel 'Thala Dan' sailed from Appleton dock in Melbourne, bound for Mawson base, carrying 30 expeditioners, plus more than a year's supplies. Deck cargo included an RAAF Dakota (DC3) A65-81, stripped of its wings and propellers, sitting on a special cradle on the main hatch cover. In the hold below was a 350cc Velo MAC which had been ridden the previous year from Perth to Melbourne by George Cresswell. 'Thala Dan' moored in Horse Shoe Harbor at Mawson on Jan. 24th, after an uneventful voyage. Unloading the 800 tons of cargo was completed by Feb. 9th, after which the crew were able to relax and take the Velo for a run around the camp in perfect summer weather. Riding was difficult over rock-strewn ridges around the harbor, and the permanent ice slope behind Mawson was fairly steep and slippery.

In late March the sea began to freeze over, and within a few weeks the ice depth was 10 inches or more, strong enough to take the weight of vehicles. The coast on either side of Mawson, as far as one could see, was ice cliffs ranging from 50 to 500 feet high, along with glaciers, ice caves, and snow drifts overhanging the cliff tops, carved by the wind to every possible shape. In preference to dog teams or heavy vehicles, the Velocette was used for coastal tours, often towing skiers or a dog sled. It was totally reliable and easy to start even in extremely cold conditions. The only modifications were dry lube on the control cables, lighter oils, a warmer spark plug, and a briquette bag tied across the crash bars to protect their boots (Mukluks), which weren't waterproof, from slush thrown up by the front wheel. Only a spare spark plug and a few basic tools were carried and on occasion, extra fuel. One of the advantages of the Velo was its relatively light weight and low center of gravity, when picking it up after a long slide on its side (after suddenly encountering bare polished ice at hight speed). The MAC was dropped many times and never sustained any damage and none of the riders were injured. Top speed was 80-85mph indicated, but would have actually less, due to wheel spin.

Bill Kellas (see color photos of his swingarm MAC, and Bill riding through the snow) claimed the sea ice was the greatest surface to ride over; it's strongest when first frozen, and even relatively thin ice supported by water is incredibly strong, if the thickness is uniform. As Winter progressed, the ice became thicker, in depth, but with the return of the Spring sun, the ice began to soften and rot from below. While the surface still looked secure, underneath it becomes like a soft sponge. The Velos were used, weather permitting, until the middle of June, when riding became uncomfortable in the low temperatures, and the wind chill factor made frostbite a daily occurence.

Clothing was mainly ex-Army, Korean War issue, and not designed for bike riding, and there were no helmets. The Velo was parked covered outdoors over the Winter, until the sun reappeared. In Spring, with daylight and temperatures increasing, riding resumed as before, but caution was required as the sea ice began to soften.

In early December of '61, the worst blizzard of the year struck, with wind speeds exceeding the range of the anemometers (which failed, or were destroyed), and visibility reduced to a few feet in blasting snow and ice crystals. This blizzard continued unabated for two days, and on the third day was still gusting at over 100 knots. The Dakota and a Beaver aircraft were at the airfield at Rumdoodle in the Masson Range when the blizzard struck. When the wind and drift subsided sufficiently to venture outdoors, the Beaver (which was behind a wind fence) was totally destroyed, and the Dakota had broken its tie-downs and had disappeared. A few days later, when the weather had cleared, Graham Currie, riding the Velocette on the sea ice west of Mawson, noticed something red, high up on the glacier top. Closer inspection confirmed that it was the dayglow red tail of the Dakota.

The plane had been blown by the blizzard about 15 miles down slope at sufficient speed, with brakes engaged, to wear the tires and wheel rims flush with the skis. It came to rest after the undercarriage dropped into a crevasse on the cliff top about 400' above the sea ice. It had then turned nose to wind and was wrecked. Because of the crevassing around the wreck site, it was unapproachable for salvage, except by cautious foot. The recovered gear (doppler radar, radios, survey cameras, and some parts) were lowered down the cliffs to the sea ice, which had become very soft and dangerous due to warming weather. They were recovered by a dog team and the Velo, towing a dog sled. The salvage was completed in two days, and on the final run, a 3 foot tall standing wave of rotten ice was visible chasing the fleeing Velo and sled!

The total mileage covered by the Velo was around 3000 miles, with individual trips up and down the coast ranging from one to 50 miles each. The bike was ridden hard to cover distances quickly, parked while areas were explored and photographed, restarted and ridden home without ever a problem. It was simply taken for granted that it would always get the crew home again, and their faith in the bike was never misplaced. At the completion of the year tour, the Velocette passed into the hands of our relief party. Its history afterwards isn't known (perhaps it's still there? - see photo of Mawson base from the late 1990's).

Frank Scaysbrook brought his MAC in 1968 to Mawson for 14 months during his stint with the Weather Bureau. He dismantled the machine in Australi and crated it for the sea voyage to the base, reassembling it in March. when the Velo was ready to go, the workshop doors opened to reveal 10 feet of snow which had to be dug through.... winter was on its way. The Velo was parked outside at all times, yet its starting habits were impeccable. Running on 80/87 octane aviation fuel and Long Life oil, three or four swings were enough to get the engine firing. The MAC was returned to Australia, and in still in Sydney with Frank's brother Dick.

[Story and photos adapted from Doug Farr and Bill Kellas' article in MotorCycling, edited by Dennis Quinlan, and published in FTDU #331, Autumn 2005.]