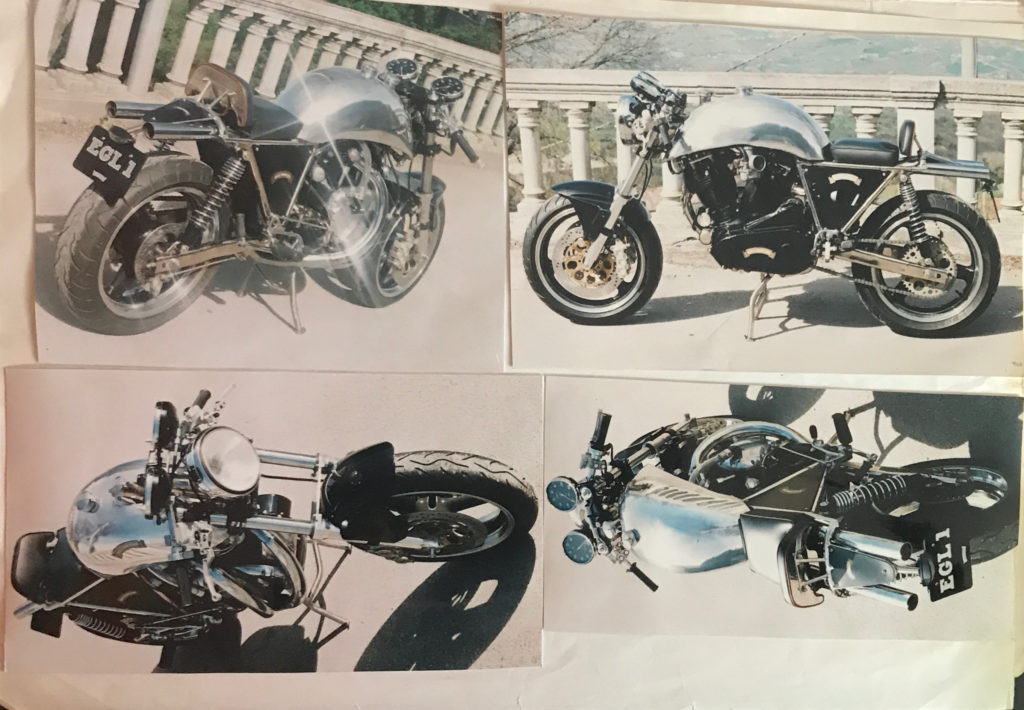

The Most Radical Vincent on the Planet?

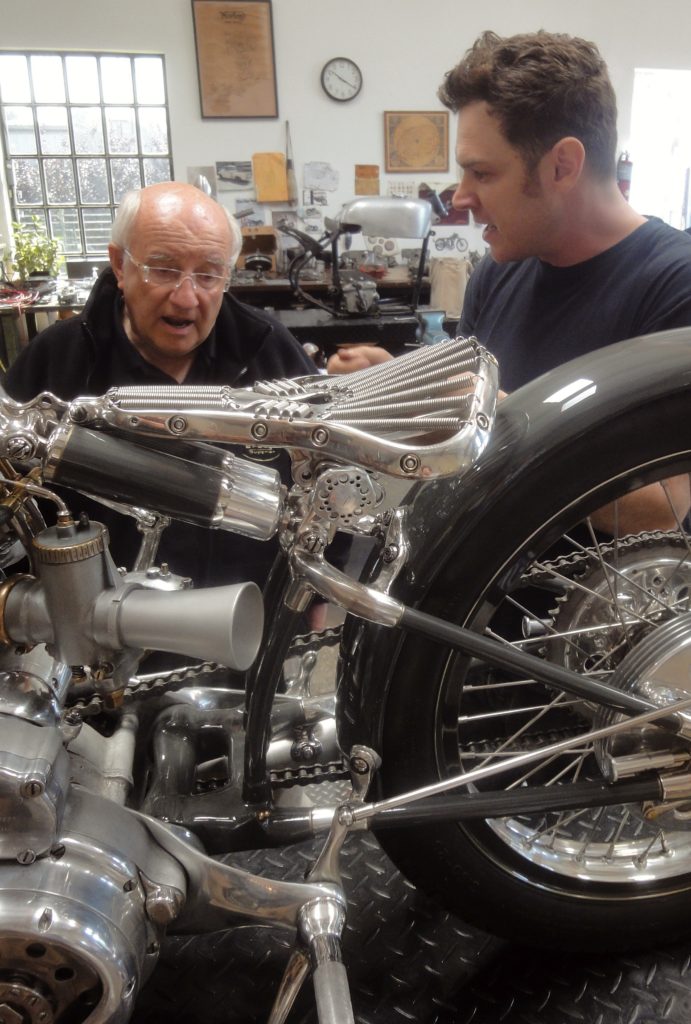

Every once in a while, a motorbike scares me. I’m not talking about some of the badly-maintained death traps I've tested for motorcycle magazines. I’m talking about radical motorbikes with the attitude of an unbroken mustang, that dare you to ride them. The Egli-Vincent Mark Fogg wheeled out of his London garage had that effect on me. Triumph supremo Edward Turner prided himself on his products, saying that they looked fast even when standing still. Fogg’s Egli-Vincent doesn’t just look fast: it looks mean. However, the bike has been dry-stored for a while and is neither road-registered nor insured so firing it up and taking it for a run to Brighton and back will have to wait. In fact, it's not even run in. That said, it is a very special machine, which is why I am going to tell you about it.

D'ya want it? The beast is for sale: serious inquiries can be forwarded here.

Montlhéry Ghosts

I first wrote about Montlhéry as a motorcycle magazine journalist in 1992. It was the 40th anniversary of the Vincent H.R.D. works’ 24-Hour record attempt in May 1952 with a couple of Black Shadows at the banked autodrome some eighteen miles south of Paris. Twenty-seven years later, on a Friday afternoon in June 2019, I was blatting down the old Route Nationale 20 from Paris with Philip Vincent-Day behind me, on our way to the Café Racer Festival at the old autodrome where his grandfather had taken the works record team on that hot weekend in 1952.

[David Lancaster's iPhone video of a Godet Black Lightning about to hit the track at the Montlhéry Cafe Racer Festival 2019]

There were too many people about that weekend so the ghosts stayed away but when Phil had finished filming, we walked about looking at all sorts of fabulous motorbikes, old and new, including the second-last Vincent Black Prince made by his grandfather’s firm. A rather intense-looking man was photographing the For Sale notice on the Prince and asking aloud if the low mileage was genuine. Knowing the machine, I assured him it was and opined that given the handling characteristics of the Series D models, previous owners were probably scared of it. Replying that he had a Black Prince and that we clearly knew nothing about Vincents, the potential new owner flounced away. Someone once described the Series D Vincents as conforming to the definition of a camel as a horse designed by committee. We felt reasonably qualified to comment: the Series D Vincents had heralded the end of Phil’s grandfather’s dreams and a Black Prince had nearly been the end of me when I test-rode it from London to Western Brittany in 1990.

Death, Taxes, and Old Bike Fever

[Prosper Keating was expelled from the Vincent-HRD Owners Club for exposing their connection to a missing £1 million-plus motorcycle collection. Here, he graciously offers his advice to motorcycle collectors on how your family can avoid such a disaster in your estate. This text has been approved by the industry professionals quoted.]

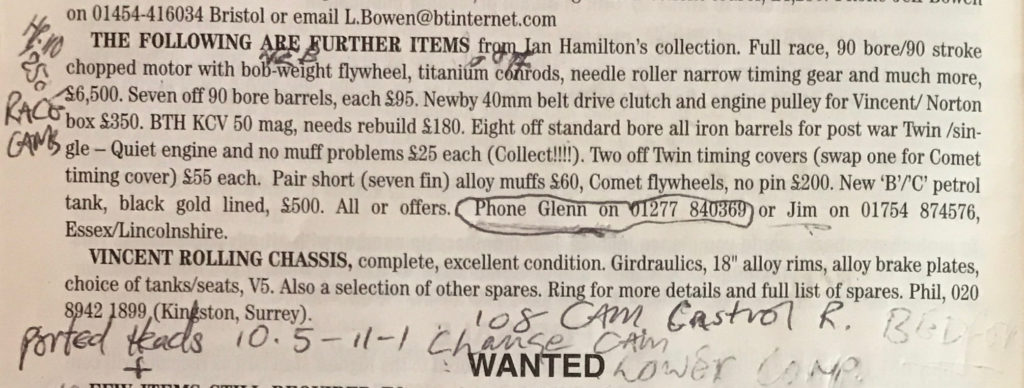

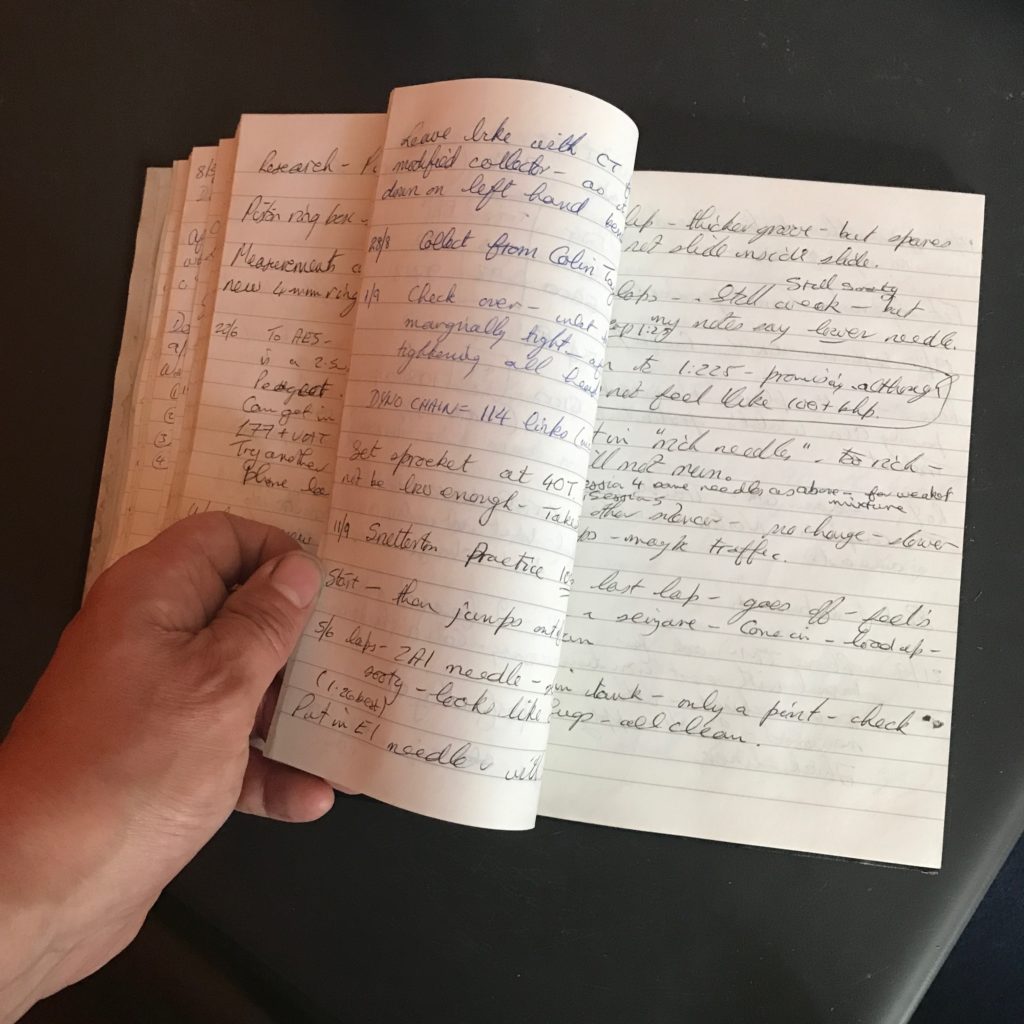

To paraphrase William Defoe and Benjamin Franklin, the only certainties life offers are death and taxes. One is absolute, but you can minimize the other by fair means or foul. However, like Death, the Tax Man wants his due and will have it one way or the other. Even if tax avoidance is your motive, it is a fool’s enterprise not to keep records of your assets (in this case, a vintage motorcycle collection) because your heirs or beneficiaries could end up losing these assets before the final reckoning, as our cases histories here show. It's surely better to pay some tax on all of your Estate than no tax on a missing Estate.

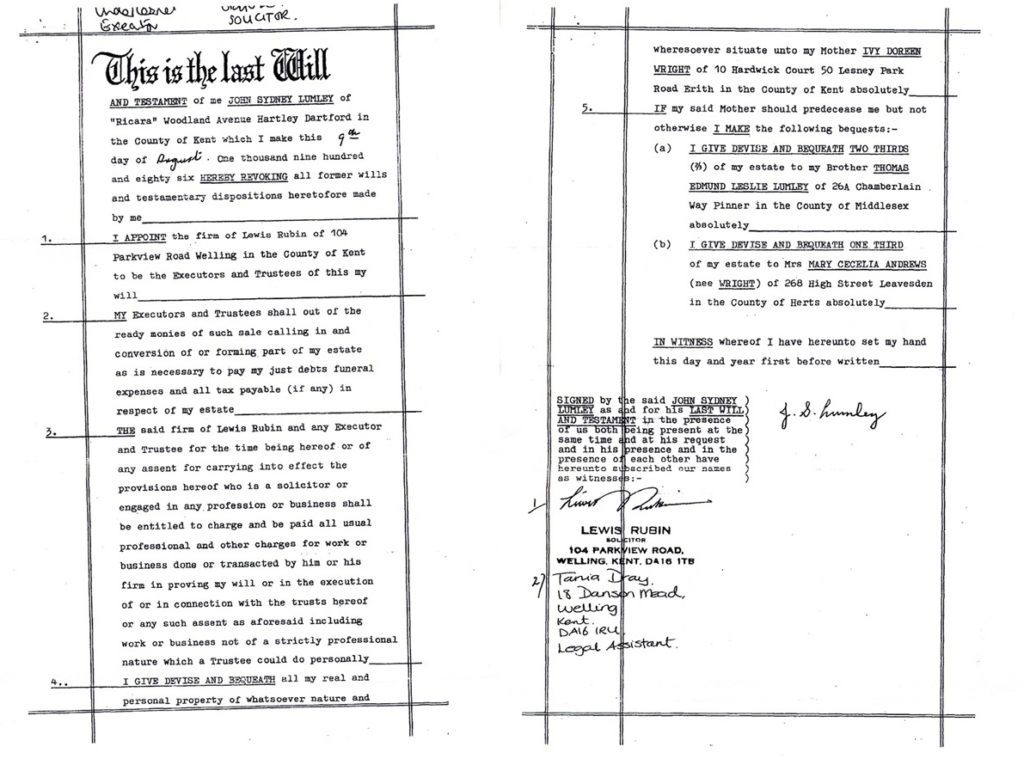

Hopefully you hold your relatives in higher esteem, so taking inventory of your possessions - including any Vincents or Brough Superiors parked in the guest bedroom - as part of your Last Will and Testament will spare them all kinds of hassle. You should also ensure that several reputable parties have copies of your Will (and any Letters of Intent) for reasons that will become clear as you read on. These are worst-case scenarios, but sadly, are all too common.

The Devon and Cornwall Police neither confirmed nor denied the existence of this file; they made no comment at all. Nor did Frank Vague’s solicitors, Merrick’s of Wadebridge, who published the death- and probate-related notices. However, it is unlikely that Merrick’s ever held a list of Frank Vague’s Brough Superior motorbikes and any related spare parts. As former Sotheby’s US and UK motorcycle consultant and valuer Mike Jackson remarks, people rarely catalogue their collections for eventual probate, or even security and insurance purposes. “I’ve been in this game for over twenty years - since I went to Sotheby’s in 1995 - and it’s a rare occasion that people do,” said Jackson. “Folk are busy. There are various reasons: sloth, nervousness about being too official. Some people don’t want to let the wife know how much they’re worth. They also think ‘Oh, if I do that and the accountant finds out, I might have to pay tax on it’. Or they think ‘Oh Christ! It’ll cost hundreds to get it done. I’ve got to buy a new lawnmower’. You know how people are.”

H and H Classics’ Mark Bryan commented: “In an ideal world, it would be great, but people don’t expect to die. Dealing with deceased estates can be a traumatic event for widows and families. Others handle it fairly well, joking about the mess their husbands have left them to clear up. It’s not unknown for ‘friends’ of the deceased to knock on doors claiming that they were promised a bike. We recently handled a collection of Hondas. The widow had been offered £35,000 for a pre-production CB750 by one of her late husband’s so-called friends. £35,000 is a lot of money but happily for the widow, she refused and we sold it for £140,000.”

Mike Jackson agrees: “When I go to see widows - it’s usually the wives of deceased parties - they are sometimes quite agitated as they tell me how ‘his friend says he was promised the bike’. Or the bikes. That is one of the most common things I hear. All these neighbors and friends behaving rather like those Vincent people, you know? People can be so ruthlessly acquisitive. And it always involves modest prices. Never market prices.”

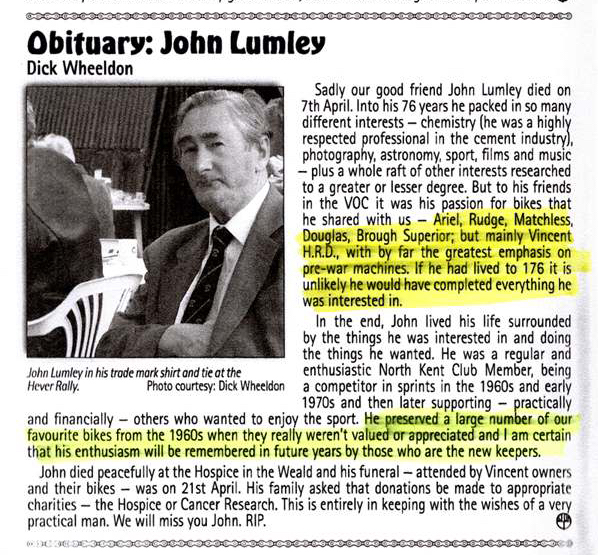

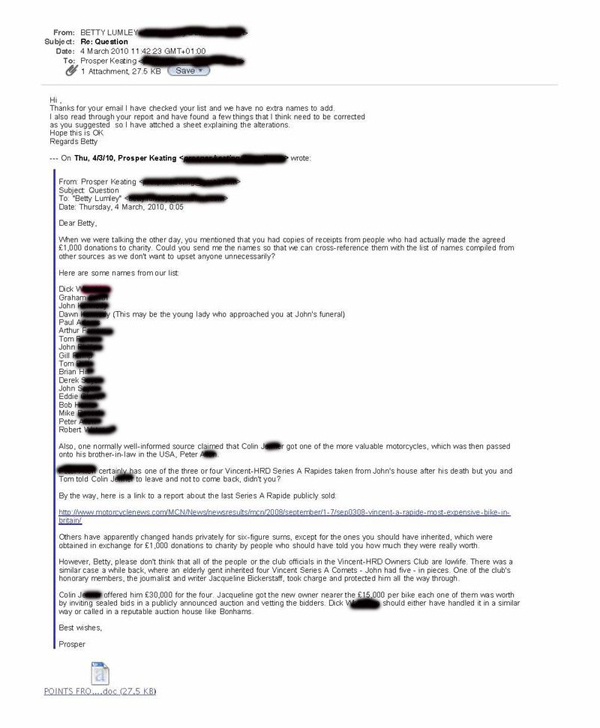

In the weeks following John Lumley’s funeral (April 21st 2009), HMRC received at least two tip-offs from concerned VOC members. They knew John Lumley and were amongst the few people admitted to Mr Lumley’s home in his lifetime. John Lumley was an intensely private man who lived alone; he was also a noted scientist in his field and a highly respected amateur astronomer. The few of us privileged to be invited through his front door can never forget the abundance of exotic motorcycles lined up in the rooms; the rare spare parts arranged on shelves with the care of an army quartermaster, the early scientific instruments everywhere, his watch collection, his telescopes and his library of scientific books dating back to the 16th century.

Vincent HRD Owners Club Secretary Andrew Everett with Club President Bryan Phillips [Prosper Keating]

John Lumley’s Executors - who had engaged Mike Jackson - made no attempt to recover any of the motorcycles that had been traced. Nor did the Executors respond to alerts regarding unexplained motorcycles and rare spare parts sold through eBay, and at autojumbles in south-eastern England, by individuals involved in the clearance of their late client’s home in April 2009. The police said they were powerless to act unless “the primary victim” made a formal complaint. Unfortunately, Tom Lumley was very ill and housebound. In any case, as Tom Lumley would later say, he and his wife Betty had been warned by the solicitors - acting as the Executors - and by “John’s friends in the Vincent club” that Betty Lumley might end up in trouble, as it was she who had given access to the property, and approval for the clearance in preparation for its sale. Betty Lumley seemed very shocked to learn of the true value of her late brother-in-law’s old motorcycles.

In the end, though, the rightful heir lost half or more of the value of his inheritance. Mr K––––––– would later remark that the Driver & Vehicle Licencing Agency was not obliged to assist him and his team with their enquiries by making vehicle records relating to John Lumley available, which is quite a revelation to anyone who believes the Revenue to be the most powerful force in England.

Those of us who knew John Lumley (as well as anyone could know such a private, reclusive man) have wondered if he left files documenting his collection of motorcycles and the other collections. If so, neither those who emptied John Lumley’s home nor his lawyers and executors - who failed to recover any of the motorcycles ‘irregularly’ removed from the Estate - have ever referred to such documentation. However, several of the ex-Lumley motorcycles touted for sale in the intervening years have been offered with abundant documentation, including original registration papers from the 1930s to the 1980s.

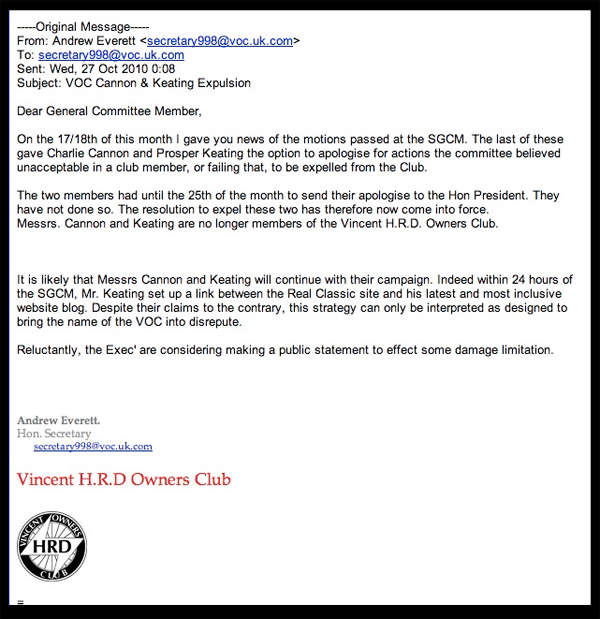

The smart ones have kept lower profiles. As for Charlie Cannon, he was expelled from the Vincent-HRD Owners Club for bringing the venerable institution into disrepute, by blowing the whistle on the disreputable behavior of the majority of its Executive Committee, most of whom are still in place. I was expelled too; it saved Charlie and myself the bother of resigning in disgust. The VOC was once a great motorcycle club and it's a shame to see it fallen so low.

Old Frank Vague, after being rescued from the hospital where his nurse had placed him, warned of “people looking around” his property to his nephews and nieces. There were stories of notes left on Mr Vague’s door, some of which reportedly upbraided the old gent for not doing more to preserve his Brough Superiors from the elements, and suggesting they should be taken away from him. Frank Vague is said to have carefully kept these notes in a cardboard box; they were probably distressing, although we shall never know now. One individual who reportedly ‘befriended’ the elderly Frank Vague is believed to have substituted a replica frame for a genuine item in Vague's collection.

Did Bonhams’ intervention save the 'Broughs of Bodmin Moor' from a fate similar to that of the John Lumley Collection? Ben Walker replies: “It wasn’t so much of an intervention. We had been advised that there was this collection of motorcycles, a mythical collection of Brough Superiors. No-one had seen them for years and years and years. It was like an urban myth which turned out to be true. They were exceptional machines and they were probably the last hoard of their kind in existence. So that’s what prompted us to take the initiative. It was extraordinary, it isn’t something we would normally do but we just felt there was no option. We’d had a tip-off that Mr Vague had left the property to live with his relatives and that the property had been effectively abandoned. But we didn’t have an address. We knew the village where it was located. We don’t ordinarily cold-call. I find it very distasteful. In this case, there was no option but to go and find the location, put something through the door and try and make contact that way. We did so by looking at Google Streetview. We went up and down the roads of this little village and found the most likely-looking property. You could see bits of car and motorcycle in the driveway."

“My colleague in the West Country went the next day to see if there was anybody there. The neighbour was looking after the property and asked him if they could help. He gave her his card, said who he was, what we do and asked if his details could be passed on to the family. She did and [the Vague family] contacted us a few days later and invited us to see the collection.”

Ben Walker is keen to pay tribute to the clubs and individuals who do go to great efforts and lengths to document historic motorcycles: “The Vintage Motor Cycle Club have an awful lot of information. Likewise with the Brough Superior Club - coming back to the Frank Vague motorcycles - who are extremely helpful and generous with their time. The Vincent HRD Owners Club have an excellent archivist although not all records are complete. The Matchless and AJS Owners Club, the Velocette club and so many others. It’s in their interest to make sure that machines are described correctly and that they are not sold purporting to be anything else.”

Above all, write it down for the sake of your passion for these machines, and the importance of recording their histories, whether they were gunned around Brooklands in 1938 or around London’s North Circular Road in 1958; or along Daytona Beach; or parked for an hour in Big Sur on the way to someplace else; or outran an angry buffalo in Kenya or some far-flung corner of an old empire; or took your parents on their honeymoon. It is all important. And if you can’t write it down for any reason, dictate it to someone.

Prosper Keating, Paris March 2018