In a tradition which predates the internal combustion engine by several hundred years, a ‘coachbuilder’ was delivered a wheeled chassis without a body, and worked his artistry for the pleasure of a few customers who appreciated, and could afford, a completely bespoke conveyance, or an expression of the particular artistic vision of that builder. When motorized ‘coaches’ arrived, some of the same carriage builders worked their magic on the chassis of a Cadillac or Rolls Royce, making an already fine automobile just that bit more special.

In an important sense, the coachbuilt auto was an expression of respect for the original design of the car, a paradoxical situation, but the resultant vehicle was never known simply as a ‘Saoutchik’ or ‘Ghia’ or ‘Fleetwood’, it was always a Delahaye with Saoutchik body, or an Alfa Romeo Ghia, or a Cadillac Fleetwood. The coachbuilder seemed to find another possibility for a respected design, perhaps one too flamboyant for general consumption, or simply too expensive for all but a very special customer.

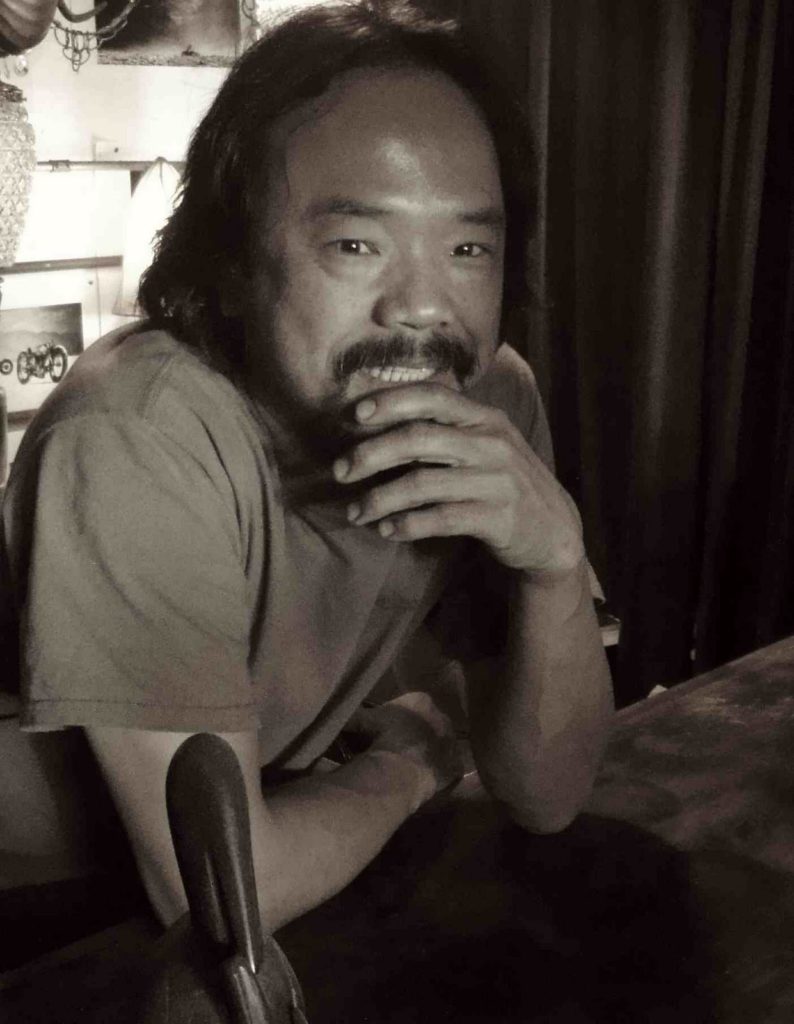

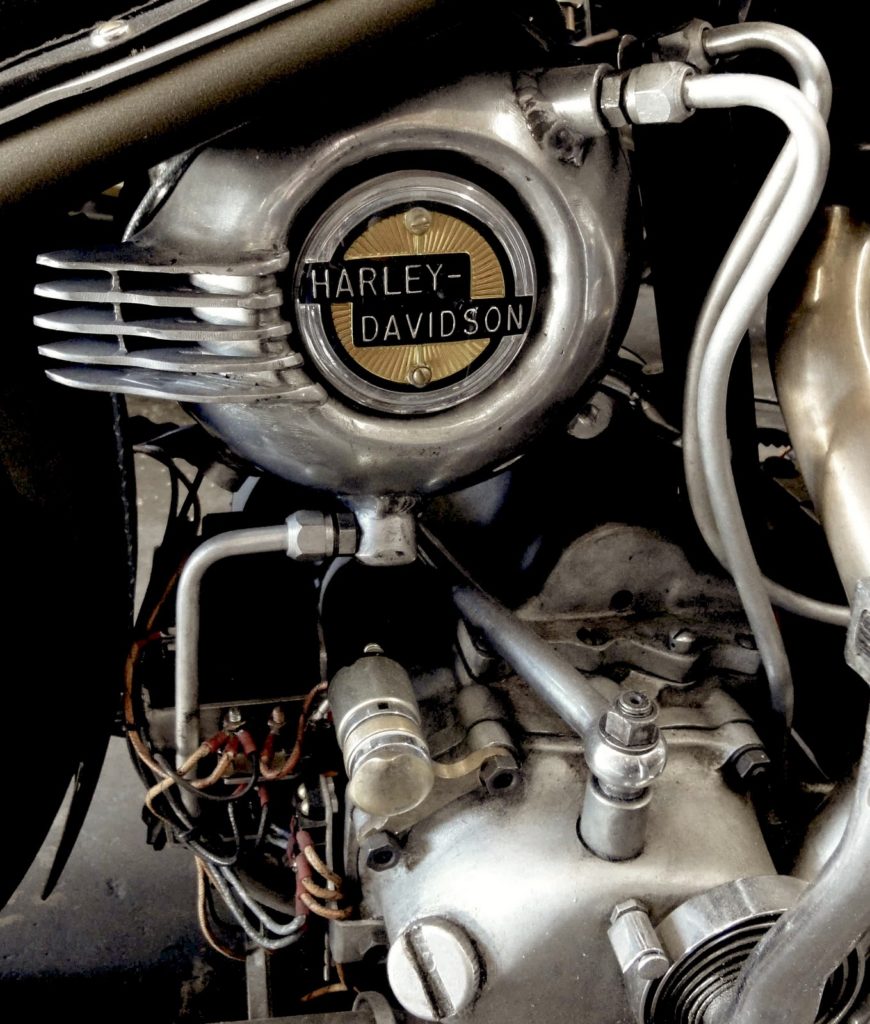

That Shinya Kimura prefers to call himself a Coachbuilder rather than a ‘customizer’ speaks to his profound love of motorcycles and appreciation for production bikes. The breadth of his interests are evident in the variety of makes which pass through his workshop, Chabott Engineering. Excelsior, Ducati, Triumph, Indian, Harley Davidson, Honda, MV Agusta, Kawasaki, Suzuki, have all been ‘Shinyized’ in his inimitable style.

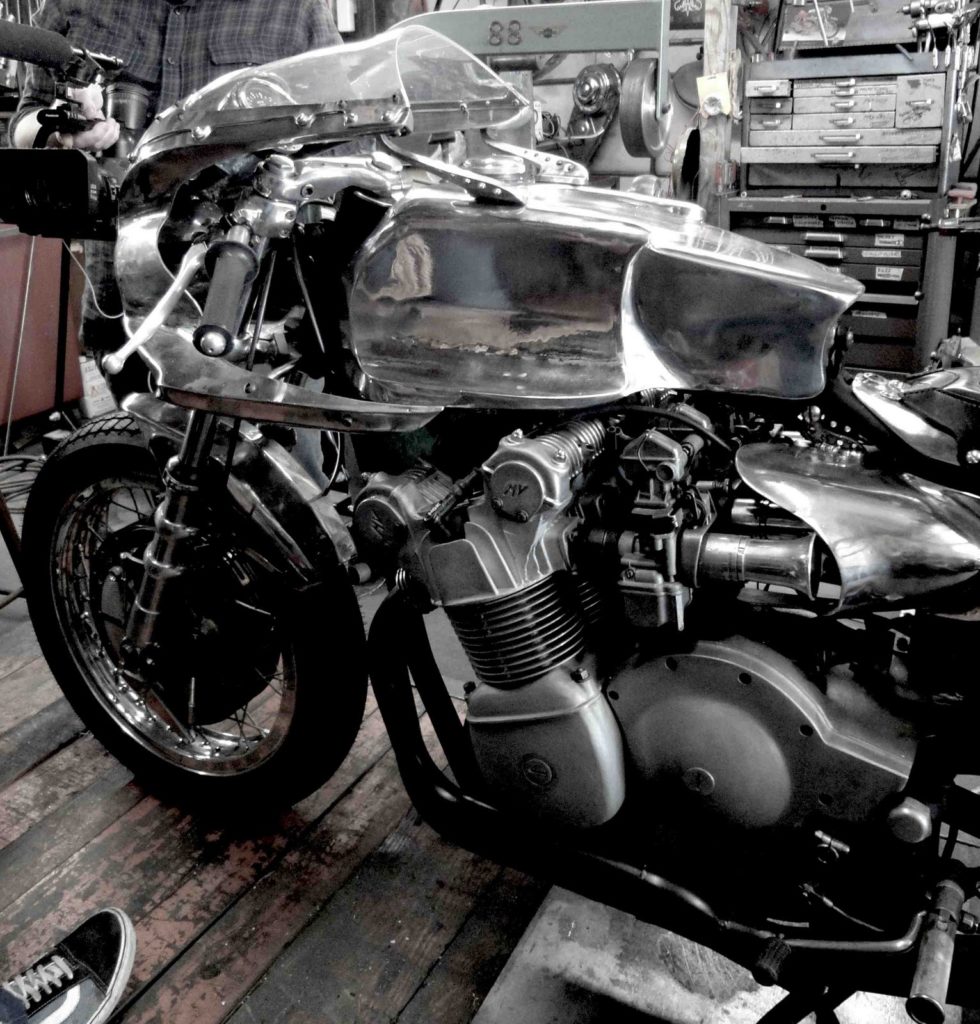

His working process is accretive and completely hands-on; Shinya makes no drawings, preferring to embrace a bike with distinctive lumps of aluminum, steel, brass, iron. A sculptor of motorcycles. While he has an ‘English wheel’, the usual tool for hand-forming smooth metal body panels, it’s only used “twice a year, as I prefer to use a mallet to shape metal.” As a result the tanks, seats, fairings, and beaten parts are clearly handmade, artisanal, with character on the surface – ripples, dings, asymmetries, tiny voids – exactly the sort of ‘mistakes’ a journeyman panel expert would avoid, but which on Shinya’s machines are evidence of the maker’s hand; a signature, a fingerprint.

When he was 15, his first motorcycle was a Honda Cub, but it wasn’t until his second motorcycle, a Suzuki OR50 two-stroke, that he began making changes, adding a larger tank from a DT1 and smaller seat, plus low handlebars for a café racer look. He wasn’t able to move the footpegs; an awkward riding position was the result. He kept making changes over the years to his motorcycles, eventually founding Zero Engineering in Japan, where he customized around 300 Harley Davidsons with a very distinctive look.

Wishing to branch further into his art, and work with other kinds of motorcycles, he moved to Southern California and founded Chabott Engineering, where the shop is minded by his partner, Ayu. He hoped his move “would make me more accessible to people, as it can be difficult to communicate with Japanese businesses from America and Europe. Now about 60% of my customers are American, the rest in Europe and Japan. The client is very important to me, as there would be no bike without them; I don’t make bikes for myself.”

Shinya interviews those who commission his machines, finding what music they enjoy, what they wear, what they eat, but takes no input regarding the direction of his labor. After finding a donor motorcycle and necessary parts, he may ask a client if the particular marque is an acceptable base for their machine, as happened when a friend offered Shinya an MV Agusta 750 to modify. Would that I could have been on the other end of that phone call – ‘I have a four-cylinder MV – can I make you a bike from this?’ Mind boggling.

Of his working process, Shinya says, “I don’t always know what the bike will look like; I don’t imagine the finished design when I begin. I would get bored if I knew what I was going to make. Every time I’m surprised…”