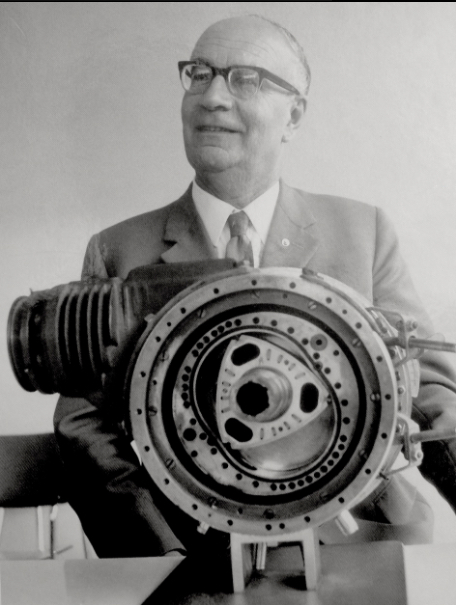

The revolutionary rotary engine designed by Dr. Felix Wankel, henceforth known as the Wankel engine, is a design of tremendous promise, and expensive vexation. It seemed the wonder motor of the future in the 1960s, and many automobile manufacturers took a out a license on the design, from General Motors to Rolls Royce, as did many aircraft and

Dr. Felix Wankel (born 1902 in Lahr, Germany) had the vision for his remarkable rotary engine at the age of 17, began working on prototypes 5 years later, and gained his first patent for this remarkable engine in 1929. His work on the motor was slow in the following two decades as he developed rotary-valve applications for piston engines. By 1957, working in conjunction with NSU, he had a fully functional rotary engine prototype, and immediately began licensing the engine, which had many theoretical advantages over a typical piston motor. First to take up this new design was aircraft engine builder Curtiss-Wright, who licensed the design on Oct.21, 1958. Curtiss-Wright has a long and deep motorcycle connection, via founder Glenn Curtiss, but their Wankel engines were mostly used in aircraft. The first motorcycle applications for this promising engine appeared shortly after the first rotary-powered automobiles, the Mazda Cosmo and NSU Spider of 1964. The first motorcycle prototypes appeared earlier, in 1960, which is the start of our survey of this remarkable design.

Motorrad Zschopau (MZ)/ IFA

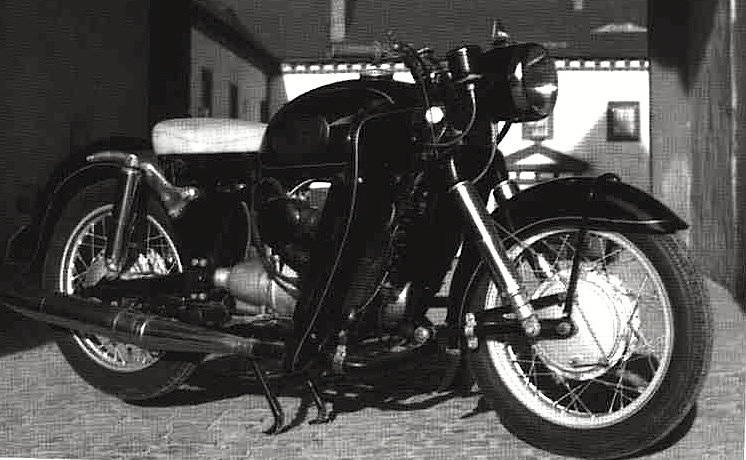

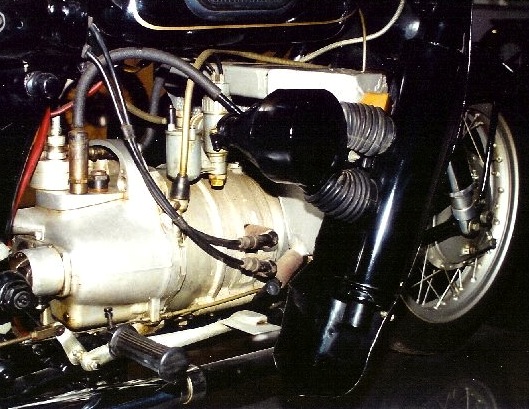

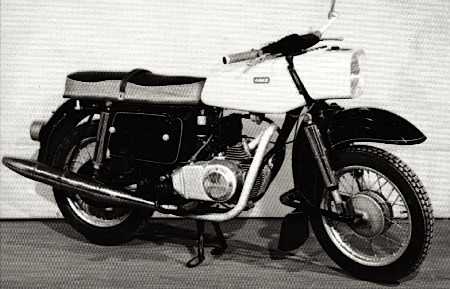

The first motorcycle application of the Wankel engine emerged from the IFA/MZ factory, from 1960. MZ took out a license from NSU in 1960, to develop Wankel engines as possible replacements for their two-stroke engines in both motorcycles and the ‘Trabant’ 3-cylinder two-stroke car. Within 3 months, a single-rotor, watercooled engine (using the thermosyphon principle rather than a water pump?) of 175cc, was installed in an IFA chassis (the ‘BK 351’ of 1959) which formerly housed a flat-twin two-stroke engine. The development team included engineer Anton Lupei, designer Erich Machus, research engineer Roland Schuster, plus machinists Hans Hofer and Walter Ehnert, who deserve credit as the first to build a Wankel motorcycle.

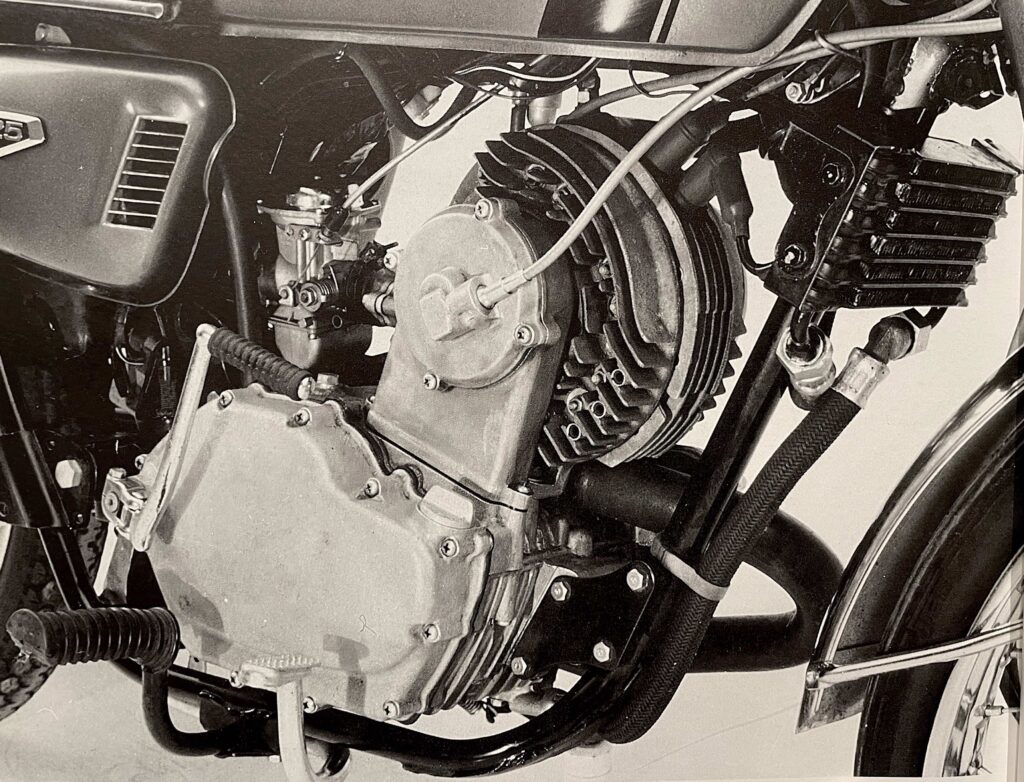

Yamaha

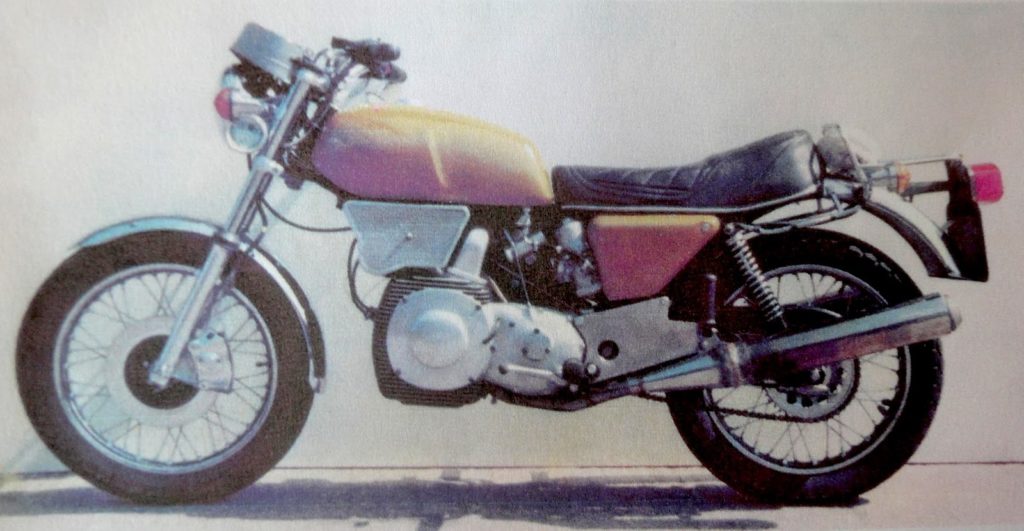

Yamaha licensed the Wankel design in 1972 and quickly built a prototype, showing the ‘RZ201’ at that year’s Tokyo Motor Show. With a 660cc twin-rotor water-cooled engine, it gave a respectable 66hp @6,000rpm, and weighed 220kg. While the prototype looks clean and tidy, the lack of heat shielding on the exhaust reveals the Yamaha was nowhere near production-ready, given the searing heat of the Wankel exhaust gases, and subsequent huge, double-skinned, and shielded exhaust systems on production rotaries.

Suzuki

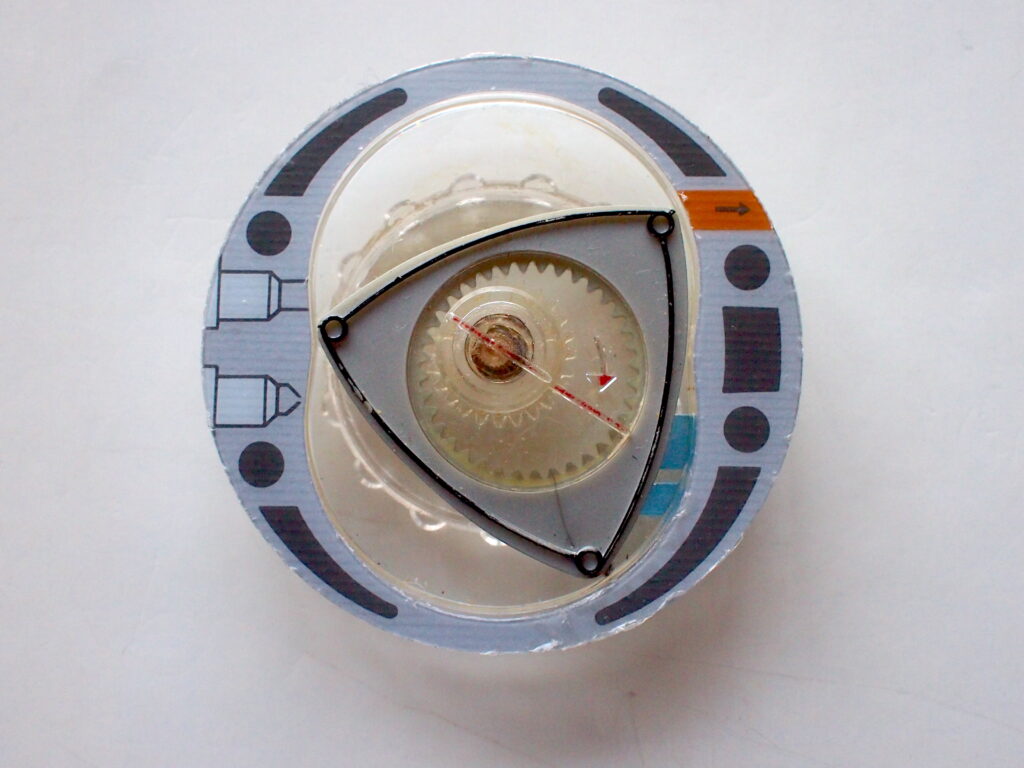

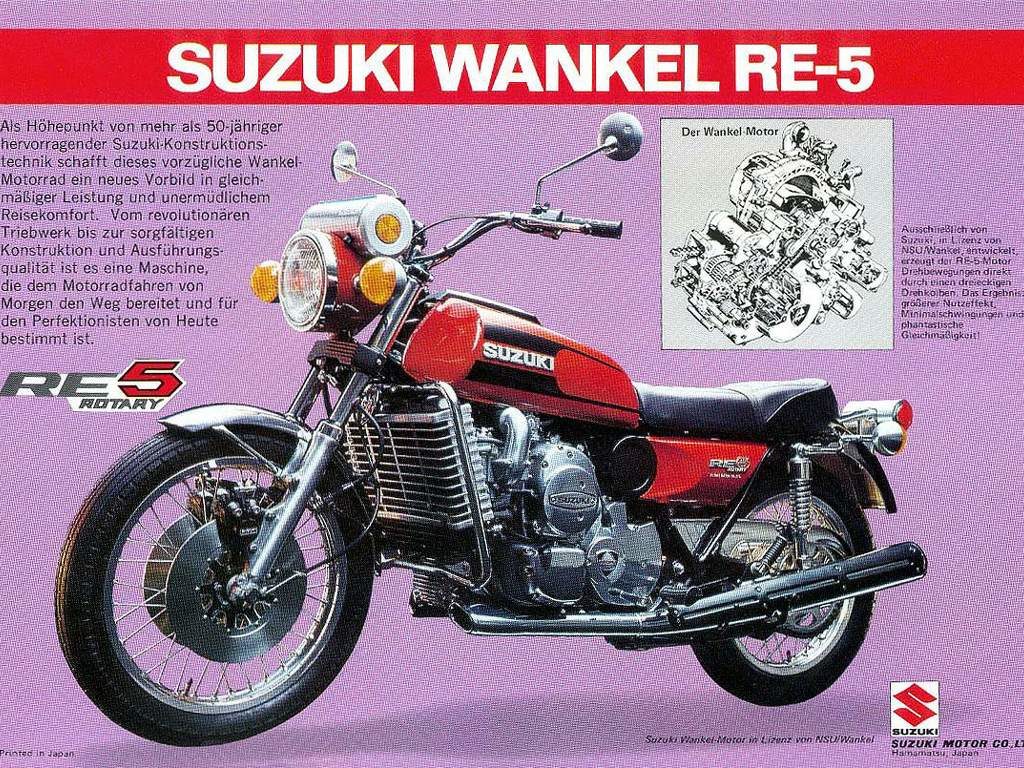

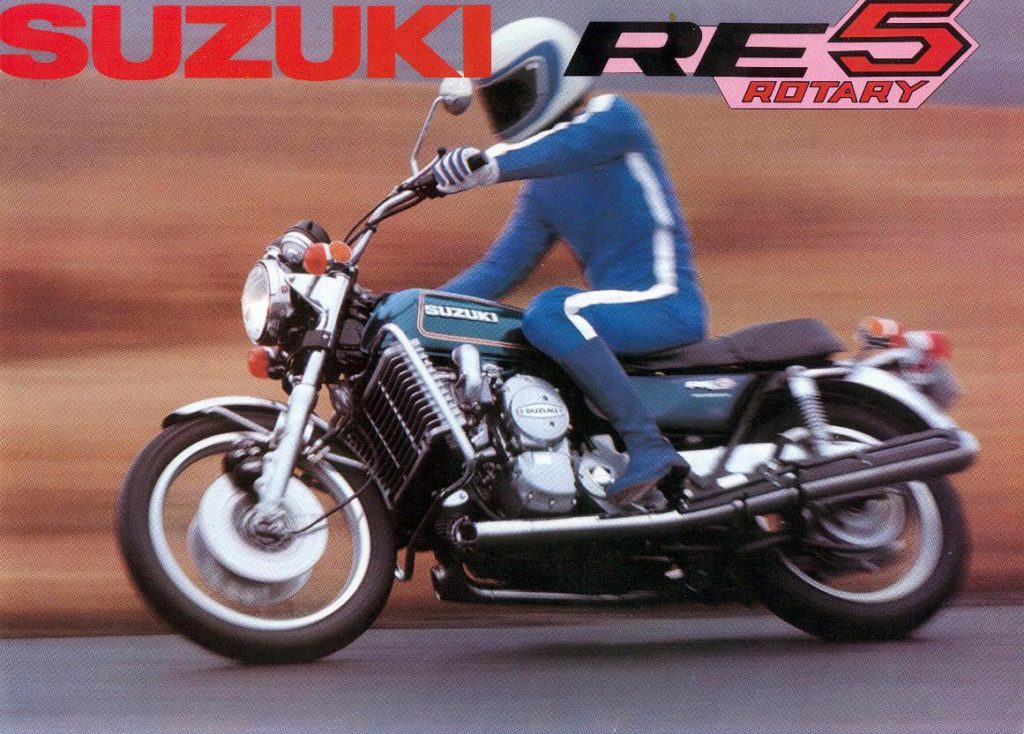

One year after Yamaha introduced, but never manufactured, their rotary, Suzuki introduced the RE5 Rotary at the 1973 Tokyo Motor Show. Suzuki licensed the Wankel engine on Nov.24, 1970, and spent 3 years developing their own 497cc single-rotor, water-cooled engine, which pumped out 62hp @ 6500rpm. Styling of the machine was reportedly entrusted to Giorgietto Guigiaro, a celebrated automotive stylist and advocate of the ‘wedge’ trend in cars, who leaked into the motorcycle world via several projects, notoriously the 1975 Ducati 860GT. Guigiaro’s touch extended only to the cylindrical taillamp and special instrument binnacle for the RE5; a cylindrical case with novel sliding cover, meant to echo the futuristic rotary engine… the rest of the machine looked nearly the same as Suzuki’s GT750 ‘Water Buffalo’.

Hercules / DKW

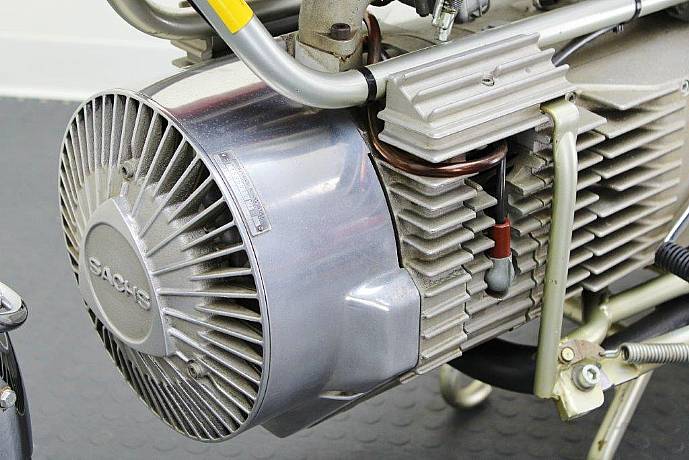

Fitchel and Sachs were the second licensee of the Wankel engine, on Dec 29, 1960, and the first with a motorcycle connection, with ‘Sachs’ the largest European maker of two-stroke engines. Sachs built their rotary as a small, light accessory motor for applications as diverse as lawnmowers, chainsaws, and personal watercraft.

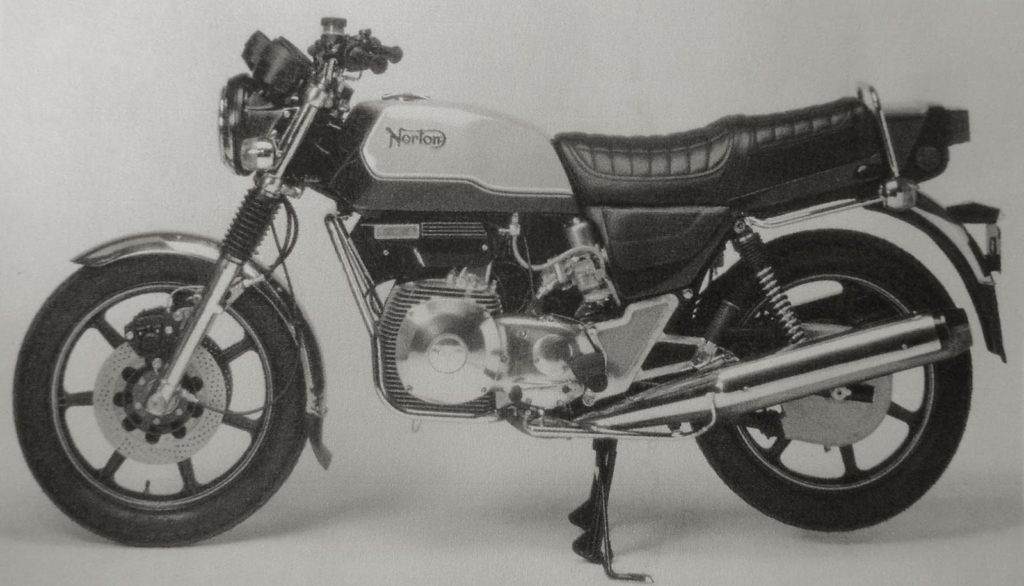

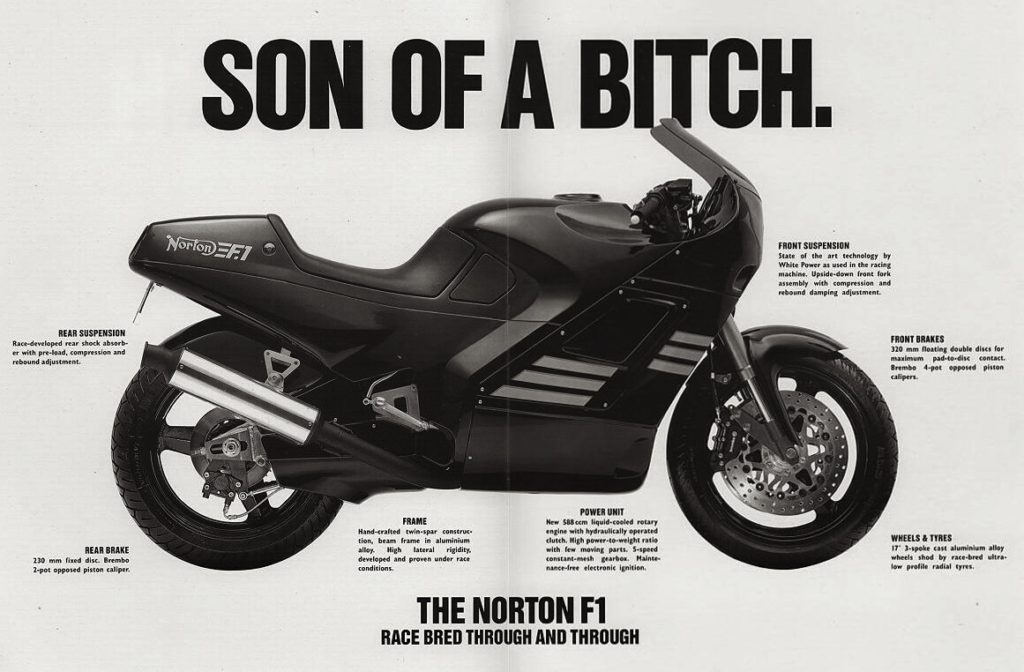

BSA / Norton

BSA felt, in common with most of the automotive industry, that the Wankel was the engine of the future, and in 1969, hired David Garside, a gifted young engineer, to begin exploration of Wankel engines for a motorcycle. Market research indicated the motorcycling public would accept the Wankel engine on fast sports machines, and Garside’s small team began experimenting with a Fitchel and Sachs single-rotor engine, and with significant changes to the intake system, gained a staggering 85% more power, to 32hp. Suddenly the experimental engine looked appealing.

Van Veen

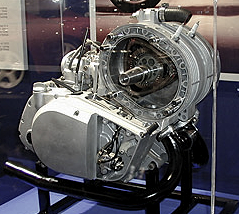

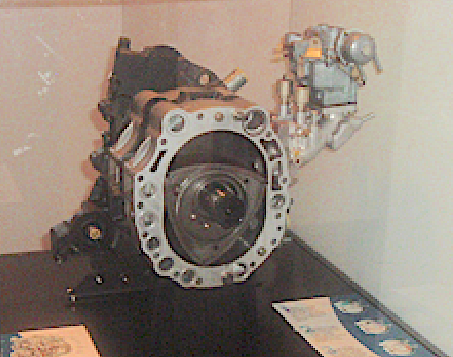

In 1976, Henk vanVeen, the Dutch Kriedler importer, saw potential in the new rotary Comotor engines, which were compact and developed good power. Comotor was a joint venture of NSU and Citroen, who invested huge sums developing a new Wankel engine for the Citroen GS Birotor. The prototype of this engine had been extensively tested between 1969 and ’71 in the Citroen M35, which was never officially sold, but 267 were given to loyal customers for beta-testing. The M35 engine used a single rotor rated at 47hp, whereas the later GS engine had two rotors, and produced 107hp from a 1,000cc. Van Veen saw this powerful and compact engine as the basis of a new superbike, and created the VanVeen OCR 1000.

Honda

Honda’s engineers did investigate the Wankel craze of the mid-1970s, although they never produced or even licensed the Wankel design. Housed in a nearly stock CB125, this test-bed project was clearly intended to see if Honda was missing out on the Next Big Thing. This prototype looks to have been built around 1973, given the paint job and spec of the CB125 ‘mule’.

Kawasaki

Kawasaki joined the fray later than its Japanese rivals. The ‘X99’ prototype had a twin-rotor engine, water-cooled, which purportedly developed 85hp. Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd, purchased a license to built Wankels on Oct. 4, 1971; the chassis of the X99 appears to be based on Kawasaki’s Z650, introduced in 1976, which suggests the date of this prototype.

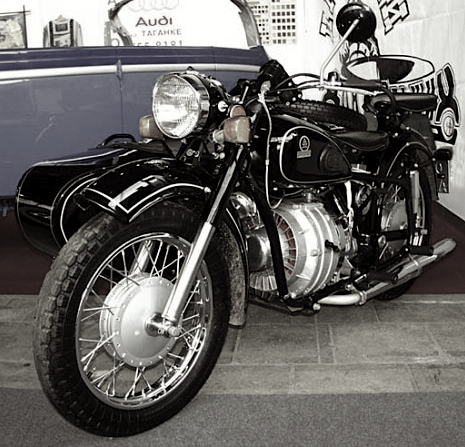

VNII-Motoprom

The city of Serpukhov, 100km from Moscow, was one of many ‘secret’ towns in the Soviet Union, where research into new technology was conducted (plus manufacture of the AK-47), far from prying eyes. VNII-Motoprom was an auto and motorcycle research institute, which created quite a few interesting machines, most notably Soviet racers such as the Vostok-4, and a few Wankel-engined bikes, completely unlicensed. The story of the Soviet motorcycle industry is little known in the West (and the East!), and deserves exploration…

IZH

Little-known outside the Eastern Bloc, Izh is the oldest Soviet/Russian motorcycle manufacturer, founded in 1929 in Izhevsk (on the banks of the Izh river) as part of Stalin’s enforced industrialization of the agrarian economy, begun in 1927 with the rejection of Lenin’s ‘New Economic Policy’, which allowed producers of grain or goods to sell their surplus at a profit – very similar to China’s first moves toward Capitalism in the 1990s. Stalin’s successful effort at creating an industrial power, where none existed previously, actually decreased the standard of living, caused widespread famine, and meant imprisonment or death for millions…although it did create an automotive and motorcycle industry. Not that 95% of Soviet citizens could afford it in those early days, although Izh sold something like 11 Million motorcycles before 1990.

Crighton Racing

Brian Crighton joined Norton Motors in 1986, as a service engineer working on their Wankel models. He was promoted to their R&D department, and began developing a scrap 588cc air-cooled Norton engine, raising output from 85hp to 120hp. The engine was installed in a prototype racer in 1987, which hit 170mph on tests, and scored a victory on its second outing. Realizing they had a winner, Norton found sponsorship with JPS, and in 1989 Steve Spray won the British F1 and SuperCup championships. Crighton split from the Norton team in 1990, and teamed with Colin Seeley as Crighton Norton Racing, competing against factory GP two-strokes of the era. Their swansong was the British SuperCup Championship in 1994, after which the Wankel engines were banned from competition.

Brilliant article! Nuff said.

Dear Paul,

Your article was very interesting; and surprisingly accurate and comprehensive. I congratulate you!

In relation to BSA / Triumph / Norton there were a few errors ref dates etc. But nothing very important.

I could list them if you wish.

It is true that a Russian delegation did visit us at Norton in about 1983, and no doubt took some ideas away.

The SAE Paper which I wrote in 1981 (SAE 821068 ) gives a detailed description of the technology of the twin-rotor air-cooled motorcycle engine.

It would be nice if you were to add that the work on the rotary engine at BSA and Norton for motorcycles then led to the development in the UK of the Wankel -type engines for UAVs, and their extremely successful (and profitable) usage in that application.

But the best is probably still to come for the Wankel.

Two recent (patented) big-step-forward innovations (by me) are likely to lead to the rotary engine being by far the best engine type for powering the genset in Series-Hybrid Electric Vehicles.

And these same improvements would now enable a superb motorcycle engine to be created. The power output of the UAV engines today is some 33% higher than the final production Norton m/cycle engine; and it can run at that power continuously, not just for a short burst.

Are you an engineer ?

If so I perhaps could send you further information.

I will send a little more history, particularly ref the 1992 MBO from Norton of the rotary engine technology for the UAV application .

Best regards

David Garside

Hi David,

I welcome your input! As I have been essentially traveling the past 18mo’s, I’ve had no access to my library, which included work on Wankels/motorcycles, so did all my research on the web, from memory, and parsed the junk from the jewels. Thus, getting dates correct and making some semblance of an event sequence was very difficult; I’m glad the result approaches accurate.

During my research, I did note many further developments of the Wankel engine, by yourself and even Brian Crighton’s current rotary racer, and would be very interested to hear more on your current activities, and opinions on the future of these amazing engines.

Perhaps an interview with you, or an article by/about you, is in order; I do cover ‘future’ issues in The Vintagent, but there’s such a direct and short line from BSA to the hybrids you mention, my readers would be fascinated I’m sure.

I’m not an engineer, but have an ability to translate the highly technical into readable prose. I’ve been following with interest several strains of engine development, from compact steam generators to wave pulse turbines, and would very much enjoy a conversation about your current research.

And please, detailed corrections on my dates, or any additions you think are important, are most welcome.

As an aside: It is my opinion that the Great Lens of History shifts its focus depending on what it relevant Today. Thus, many motorcycle writers have for decades considered steam and electric motorcycles irrelevant, and even dismiss the very first powered two-wheelers as ‘not motorcycles’ because they used steam in 1862, and not internal combustion! I have argued with Kevin Cameron of Cycle World, an educated and thoughtful man, about this very point. ‘Discarded’ technology like the Wankel, compact steam generators, and electric motors, will come again to relevance in they eyes of the public and historians…clearly electrics already have.

This article on Wankels is my attempt to drag history’s lens back toward the Wankel (I’ve already done one on Steam), as we are coming out of a long period of technical doldrums, in which the hegemony of the piston engine was undisputed, and other research barely funded or noticed. It becomes clear to all that an engine of much greater efficiency will of necessity dominate future transport, as resources dwindle and demand grows, and it is my sincere hope that shedding light on such projects, even as a historian, will bring awareness to and support of these efforts. The power of the media should not be underestimated in this regard…

all the best, Paul

Thank you for your contribution.

A new rotary motorcycle….very good gentlemen!!

Very interesting article. My only Wankel experience was borrowing my brother in laws Mazda RX3 for a week in the 70’s. Very impressed by the power. Have never worked on or ridden a Rotary bike, and had no idea that so many companies had looked into building them.

For some reason I googled world’s largest and smallest wankel and came up with the following. http://www.rotaryaviation.com/rotaryhistory.htm#Part3 will bring you to an article about an engine Curtiss-Wright built in 1960. It’s a 31.5 liter single rotor that made 750 hp.Ingersoll Rand further developed this design into single rotor 550 hp, and double rotor 1100 hp motors. They were used for gas compression and power generation.

berkely.edu/news/media/releasees/2001/04/02.engin.html brings you to a press release about a micro rotary that runs on hydrogen or propane, I believe, and are extremely small. They are supposed to last longer than batteries of the same weight.Very interesting subject.

Paul,

Nice work on the Wankel motorcycle feature, well done indeed. A couple of comments: Cook Neilson was editor of Cycle, not Cycle World. Not sure what you mean by “notorious” in the context of Cook’s Norton Rotary article. The mule he rode for the piece on the roads near Kitts Green was, by his admission, still quite a way from production spec. He was fairly full of praise for the bike’s performance potential, describing it as “capable of jerking the headlights out of a good-running Trident [which was along for comparison], and the Trident is no slouch.” His caveats came from his view of NVT’s ability to pull off this program, given their financial straits at the time. (Cycle’s UK columnist, Jim Greening, was posting columns about NVT’s survival regularly during this period.)

The Honda concept rotary chassis shown isn’t a CB125—the TLS front brake and fuel tank are too large for the period 125. Looks to be a CB175.

As I recall from factory documents I have in my home archive (I’m writing this from the office), BSA bought its rotary rights from Curtiss-Wright. C-W demonstrated much success with direct-injected, stratified-charge rotaries, showing diesel levels of fuel consumption and multi-fuel operation. Emissions in tests were encouraging. But C-W’s interest in the rotary license ranged far beyond its own light aircraft propulsion and aero APUs. Very quickly C-W began extending license agreements to the auto industry, including GM and American Motors, plus Mercury Marine (outboards), John Deere, Ingersoll-Rand, and others including BSA. This was a gravy train for C-W. Then the U.S. Clean Air Act came.

For Vintagent readers, it might be useful to have included some reasons why the rotary failed to live up to its promise (apex seal issues, rotor-tip sealing), as well as mention that Mazda recently threw in the towel on its RX rotary program. Besides powering military drone aircraft, the rotary’s future may be in running within a very defined rpm map, powering series-type hybrid cars.

Plus, it just looks silly in a motorcycle frame!

Keep up the great work.

Best,

LB

LINDSAY BROOKE

Senior Editor | AUTOMOTIVE ENGINEERING INTERNATIONAL

SAE International

Hi Lindsay,

thanks for your comments!

I still think the Honda is a CB125, as that paint scheme wasn’t found on the CB175 – the ‘swoosh’ stopped below the tank bottom.

Compare this:

http://homepage.ntlworld.com/david.walsh.net/images/HondaCB125.jpg

With this:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/dsp_custom_photos/366319819/#/photos/dsp_custom_photos/366319819/lightbox/

Not that it matters much; what I’d like to know is, from whom did they get the right to build this motor? Or was it a ‘graft’ job with an existing engine (ex-snowmobile?)…it appears to be straightforward…check here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QThl-AALfTM&feature=related

According to my research, BSA did indeed buy their rotary rights from Felix Wankel’s ‘holding company’ in 1972; we can ask David Garside if this is correct. It’s also possible that Norton was in contact with Curtiss-Wright for some of their experience developing the engine, and licensed this as well. C-W patented many improvements of their own on Wankel’s design.

I’ll get to the whole advantage/disadvantage discussion of the Wankel motor in another post on Felix Wankel himself, and discuss the development difficulties.

yours, Paul

Hi Paul.

Very fine post. And what a grand litany of posters.

There is a Vincent connection to the rotary.

In his later years Philip Vincent was working on a rotary-type engine. Robin Vincent-Day, who began a romance with Dee, PCV’s only daughter, in 1974 and married her a little later, assisted PCV in preparing drawings for the rotary concept, as he worked in the then embryonic photo-copy industry.

His recollection of the work is here – http://www.thevincent.com/PCVAfter1959.html

Robin had also just bought himself a Rapide. Later, Dee and Robin were blessed with a son, Philip, whom remains active in the Vincent Owners Club.

It seems Vincent was very alive to the potential of the rotary engine but the determination which saw him produce such fine motorcycles during his most productive period, did not, perhaps, serve him as well in the years after. PCV’s idea was that his engine would be manufactured from Silocan Nitride, a ceramic material.

His rotary engine is chronicled in LKJ Setright’s book Some Unusial Engines, (1975) .

Having ridden the Norton F1 JPS production bike, I can confirm that with its Sponden frame, and smooth, smooth engine – more than a match for its rivals – it was a stunning machine. But why would a buyer with 150bhp on offer now, think of a rotary engine?

Dave Lancaster

Great article. An interesting point about the heat and noise that took me years to realize is that piston engines have a brief time between the explosion and the valve or port letting the gasses out. A Wankel lets those gasses escape, essentially, while it is still exploding! Thus the heat and noise.

Anonymous said…

I read and enjoyed your blog on the rotaries.

If you’d like to to an expanded version on the history of the Norton rotaries I also suggest you talk to Joe Seifert, owner of Andover Norton. As you probably know, Andover Norton is the supplier of authentic Commando AND Rotary parts. They also have an extensive quantity of documentation from the former Norton factory.

http://www.nortonmotors.co.uk/

Joe Seifert

-Dave F

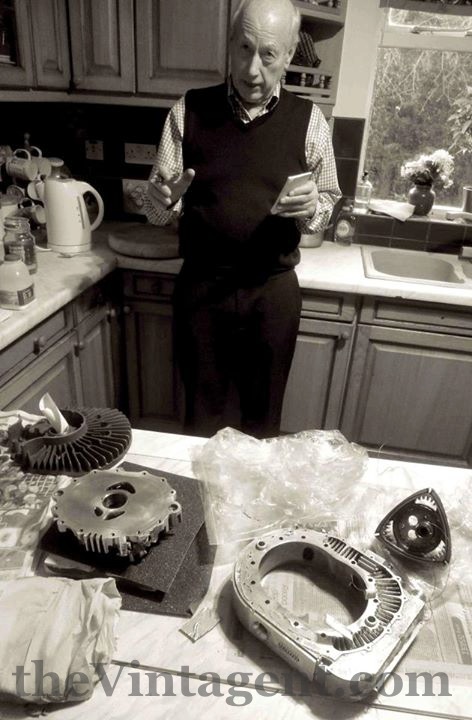

Hi Dave,

I interviewed David Garside in 2011! I’m off to London on Thursday, and will catch up with him on the 9th…very excited to meet an unsung hero of the bike industry. Yes, I’d like to meet Joe Siefert, and Brian Crighton too. I hear Crighton has recently built a 175hp/120kg super-rotary…after researching them, I’d love to own a hotrod Norton rotary; talk about rare…

The first Wankel-powered motorcycle, an MZ of 1967

Hi,

nice article!

But the first Wankel-powered MZ (175cm³, 24PS) was built in 1960 on basis of a MZ BK 351 (built in 1959, also a prototype as follow-up for the legendary IFA/MZ BK 350 ). The prototype you’ve shown is on a basis of a MZ ES 250/2, built in 1965.

You can read more about it on the following websites:

http://www.wolfgang-dingeldein.de/wankelig/historie/hist-mzwankel.htm

http://www.gvongehr.homepage.t-online.de/sonder/wankel/wankel.htm

Best

M.

PS: MZ had a license for the Wankel-engines until 1969!

Hello ‘M’,

many thanks for your information; it will be incorporated into my article, with credit of course.

I find no record of MZ/IFA taking out a license for Wankel development – this is curious; I do note that one of these sites claims an expiration of a Wankel license in 1969. In my research, no Eastern or Soviet license was sold…but of course, there may be more to the story!

From old to new, cool! Vintage motorcycles to a new model, as time change design changes too. Good job!

The Vintagent said…

Here’s the info on the Ingersoll Rand IR 2500 engine, the largest Wankel motor produced to date:

http://www.rotaryaviation.com/rotaryhistory.htm#Part%203

Anonymous said…

Can I have the right article for the Ingersoll Rand Biggest Wankel Engine (IR-2500)

Some corrections regarding Soviet usage of Wankels.

The Dnepr MT-9 chassis is not R71 based as it uses a swingarm rear suspension and is modelled loosely on the post-1955 BMW chassis. The RD-501B engine and the later RD-515 engine were also trialled by IMZ (Ural) in their motorcycles but never went beyond prototypes.

VAZ (Lada) actually produced a couple of series of production engines See http://cp_www.tripod.com/rotary/pg07.htm

The Izh factory was actually founded by Alexander I in 1807 and constructed it’s first prototype motorcycles with sidecar drive in 1929. See http://www.izhmash.ru/eng/history/ and http://archive.izhmoto.ru/eng/

The IZH “Rotor Super” (actually IZH Lider – Leader) was designed for Government use – KGB (now FSB), GAI (now GIBDD) and Militsas (now Politsas – Police). It used a production VAZ twin rotor engine, probably the VAZ-413 or VAZ-4132.

Stephen, many thanks, I’ll update the post. Finding good info (in English) about Soviet motocycles is improving, albeit slowly. Interest is growing though, especially as Russians begin to re-value their history.

Interestingly, there was an article on Izhmash in the NYT today, about the popularity of Kalashnikovs (actually their civilian counterpart, the Saiga) in civilian markets, with sales having increased 50% in the US in 2011.

Dear Sir,

If you send an e-mail me, I will send you information about my work on the Wankel rotary engine.

I am an inventor and I have no particular material, look for a research center to put into practice my work in a newly developed rotary engine with the ideas of my project BRUNTOR. My job, I’ve put into practice in a rotary engine that got SACHS with outstanding results that will send you.

After verifying the outstanding results achieved with my work, develop a new rotary engine may be the best internal combustion engine invented by man and also a motor “green.”

The most important idea of my project – called NEW DESIGN – ensures permanent seal between the chambers of the motor, this idea is patented.

With the idea – NEW DESIGN – The rotary engine is best suited to consume hydrogen.

Greetings:

BRUNTOR. BRUNO – ROTOR. Elias BRUNO Ribeiro.

========== =============== ==================

The IMAGINATION can build the knowledge,

the knowledge can LIMIT the IMAGINATION.

A very interesting article and tremendously good work!

Some thoughts: maybe it was a wrong decision to use the Fichtel & Sachs engine as a basis for a motorcycle. The F & S engine was conceived as motive power for position independent devices like chainsaws where a pressure lubricated engine would not have worked – there is not much use in an oil sump when the engine is operating upside down. This led to the Hercules and Norton motorcycle engines being fed by two stroke mixture where proper purpose-designed engines have an oil sump. For Fichtel & Sachs and their Hercules subsidiary it was a quick and cheap hack to use an existing engine mated to an existing gearbox to create a nasty motorcycle but Norton bet their existence on it. Hmmm.

Herules did one bike much better than the “vacuum cleaner” W2000 and this is lacking from your otherwise comprehensive list. For ISDT type sports events Hercules created a Wankel bike heavily based on their successful competition bikes. They used the lower parts of a 250cc F & S six speed two stroke engine, replaced the crankshaft with a bevel drive and put the trochoid on top of the crankcase in a horizontal position, mating the eccentre shaft to the bevel drive below. This bike looked pretty conventional except for the exhaust exit position at the side of the engine. Otherwise it could have been any two stroke engine guided by its looks. There are photographs in the internet showing these bikes (http://www.classic-motorrad.de/galerie/albums/userpics/10001/Hercules-Wankel-Motor.jpg, http://www.southbayriders.com/forums/attachments/23098/)

. In the German press a production of this bike was heavily rumoured at the time but of course nothing came from that.

When talking about hot exhaust gases from a Wankel engine, I remember a dark summer night with a fast blast along a deserted Autobahn where I followed an early Mazda RX7. This car had an exhaust silencer immediately at its rear bumper and two short exhaust pipes protruding from there, giving a sight of the innards oft he silencer. The guy in the Mazda was really driving hard and you could tell the throttle position by the colour of the visible interior of the exhaust silencer. Everytime he went truly fast the two exhaust pipes showed a bright yellow, under slowing down this turned orange first, a dark red then and invisible shortly afterwards. As soon as he used his right foot again the exhaust heated up from red to yellow within five to ten seconds. I followed that car for about fifty miles, continuously watching this glowing exhaust. It was a truly amazing sight that I never forgot. This is the price you pay for a vibration-free engine having a combustion chamber that is disastrously inefficient from a thermodynamic point of view, allowing a tremendous amount of heat to escape through the exhaust instead of being used for creating motive power.

Anonymous said…

What a great, informative article! Enjoyed it tremendously, thank you Paul!!

I recall a comparison test of the Suzuki RE-5 versus its sibling GT750 and others, including a Harley, all under the guise of seeking out the best touring bike at the time (1975).

The RE-5 outhandled every last one of the test bikes, perhaps due to a more favorable weight distribution.

As I recall, Suzuki had significant issues with their dealers’ service network – to support the RE-5, some $5000 of diagnostic equipment was necessary, the cost of which came directly out of the dealers’ pockets.

-Michael

Hi Paul,

Having spent some time working on the NRS588 racers in 1992 I am surprised that you have omitted the fact that one of these machines won the Senior TT in 1992 in the hands of the Late Steve Hislop, who also set a race record which lasted quite a few years. This was the first time a British bike had won a Senior TT for 31 years.

The Racers were initially developed by Brian Crighton in his spare time and first appeared at Darley Moor in 1987, ridden by Malcolm Heath to a creditable third place. John Player sponsorship was secured for the next few years and the machine was ridden by quite a number of top men, ultimately by Ron Haslam and the late Robert Dunlop in a team that was managed and led by Barry Symmons until 1992. Unfortunately the JPS sponsorship was due to end at the end of this year and, as you mentioned, financial problems that had been highlighted in a television programme put paid to any new deal and the team folded at the end of the season.

In 1992 a new team was formed independently by Brian Crighton and Colin Seeley which ran until 1994, taking the British Supercup championship with Ian Simpson on board.

Crighton has continued to develop the machine in a small way with the support of Stuart Garner at the reformed Norton factory and had a brief and unsuccessful outing at the TT in 2009 when it failed to complete a lap in practice. It seems to have slipped into obscurity again since then.

An interesting piece just the same!

Pete Causer

Dear Paul, great article and one of interest to me, I have always had a soft spot for the rotary waited for the day that the last of the problems got sorted and at last see the potential was seen. Well I was fortunate to work with the great Brian Crighton ex-Norton over the last 2-3yrs and last year the CR 700P was born. Worked. and was a fantastic launch at Mallory Park where ex-British champion and TV BSB presenter tested it…WOW… I had the job of tech drawings and visual design. It’s worth a look and if you haven’t seen it can do so here: http://www.coroflot.com/Leett/CRIGHTON-CR-700P

Thank you

LT

Nice to know that mr David W Garside is active and with the same ingenuity as before. I’d always like having more feed-back about his results with Reed-valves, I had a letter from him in the 80s, and also a reference to find about the intake ducts, intake duct plate hole, intake ports, and out of rotor incoming mix temperatures. Regarding the Ingersoll-Rand huge engine, the info I’m aware of is: ‘Detonation Characteristics of Industrial Natural gas Rotary Engines’, T N Chen et al. SAE paper 860563. I still ignore if this T N Chen is the same T Chen heading Wankel research in China. If you provide with a workable e-mail address for this site, I can send a small list of what I consider basic RCE references. I’m not an engineer, I collected Wankel documents the same others collected movie stars pictures, and own some engines in different sizes.

All interesting discussion. Those interested in reading David Garside’s 1992 SAE Technical Paper on Norton’s rotary developments can access it from the SAE.org website: http://papers.sae.org/821068/

German engineering consultancy FEV has had Wankel-based ‘range extender’ hybrids in European demonstration fleets for a few years, in which the compact, small-displacement rotary is tucked under the rear of the car and runs at steady-state rpm to optimize its emissions profile. Mazda has arguably pushed the Rotary as far as any automaker regarding emissions compliance and overall durability and is still developing the engine–the RX is to Mazda what Desmo is to Ducati, part of the brand DNA. But given increasingly stringent global emission regs and the continued refinement of Otto cycle piston engines, Mazda’s resurrection of the RX and the industry’s re-connection with Wankel technology in other than series-hybrid applications, is to me doubtful.

And in bikes, the Rotary still looks like something out of a commercial air conditioning unit….

In my conversation with David Garside (2011) he emphasized how perfect a small rotary would perform as a generator motor for a hybrid. Wankels work best at a constant RPM, so make perfect aircraft and auxiliary motors – they’re incredibly simple and very reliable. Their #1 application now, as you know, is powering military drones – I’ve had a lot of response from Israeli fans/coworkers of Garside, who work in the drone industry!

Paul, what bike is that at the top of the page beneath the title?

It’s a prototype Norton rotary racer. I’ll dig up more information – it deserves a full article!

It was the first bike I did a genuine 100mph on !!! As a young lad in the 70’s, my dream job came true and I was offered an apprenticeship with the Suzuki distibutors in Adelaide, South Australia – Cornell Suzuki. The workshop foreman was given a bike to be used for daily commuting as part of his salay package. The bike was an early RE-5, aparently one of a small batch of pre-production bikes sent out by the factory for some evaluation and feedback, it was well used and a bit rough around the edges when I first had aythig to do with it. Despite some clangers I pulled early inot my time there with a few customers bikes, I was given the task of regularly maintaining the bike. I remember the weight of it, a monster to get up on the benches, but the engines sound was extraordinary. The factory supplied a range of diagnostic and testing equipment in a classic 1970’s briefcase, it looked pretty hi-tech for the time. ignition, carburettion, and exahust gas analyzing could all be done quite simply, even had to use a “special RE-5” engine oil to cope with the high temperatures. I remember the spark plugs being something special too, and about five times the cost of a standard one. The thrill, though, of riding it the first time … I’ll never forget. The bike had a lot of miles on it, the foreman living way out in the ‘burbs so it got about three hours of running a day, his mis-spent youth as a monkey on a terrifying speedway sidecar hack tempered him with a heavy wrist – I was always putting rear tyres on it ! It ran a charm though, very smooth and quiet. The road past our Airport used to be an uninterupted two mile stretch of dual lane tarmac, so of course our favorite test run. And one day I thought – what the heck, and wrung it’s neck until I got to the ton … my first God moment, especially as it was starting to weave all over the place !!! Eventually we fitted a new rotor unit – free from the factory, ( in fact, they sent over a whole pile of parts ) as we were working on it the foreman told me that the factory had a performance kit tested in Japan as the std out-put was only 40%of it’s potential, but decided not to release it to the public as the header pipe would glow red 1 Good times.

Soviet Izh named as Izh Leader

c/o Paul d’Orleans

Hello Paul,

have seen your pretty good article about the motorcycles / motorbikes with rotary engine.

Don’t know, whether you’re only writing about motorcycles. Perhaps you would like to write something about the OMC rotaries, too ? (snowmobiles + outboard engines). I could send you some documents / papers as a “starter kit” (all PDF).

Let me pass greetings from David Garside to you. He’s well + alive + will help you with details + answers, if required.

eg BSA (and later Norton) took a Licence from Audi/NSU, NOT from Curtiss Wright.

Currently David is developing a rotary engine to run with hydrogen as a range extender.

Here’s David’s e-mail address, if you want to say hello: davidwgarside@btinternet.com

Best regards

Frank Herfert

(f.herfert@gmx.de / Germany)

Thanks Frank, we would be interested in information on other rotaries! I had the pleasure of interviewing David Garside in his home perhaps 7 years ago, I’m glad he’s still keeping busy!

all the best, Paul

Very Mr. mine:

If you send me an e.mail, I will send you information about my work on the Wankel rotary engine.

My work, I have put into practice in a rotary engine SACHS with which I got some extraordinary results that I will send you. The performance of the engine increased very significantly and the combustion of

Gas is much better than combustion in the alternative engine of 4t., this is logical and possible since the rotary engine has a combustion stroke 50% greater than that of the reciprocating engine.

After checking the extraordinary results that are achieved with my work, a new rotary engine that could be the best internal combustion engine invented by man and also an engine

“ECOLOGICAL”.

The most important idea of my project called – NEW DESIGN FOR ROTOR VERTICES – ensures permanent sealing between the working chambers of the motor.

With the idea – NEW DESIGN – the rotary engine is an “ECOLOGICAL” engine.

Greetings: eliasbruno23@yahoo.es

IMAGINATION can CREATE KNOWLEDGE,

KNOWLEDGE can LIMIT IMAGINATION.

================================================================================

Dear Paul,

I was a member of the Van Veen OCR1000 development team 1973-1978 and want to thank you for the initiative for your interesting review about rotary motorcycles,

my only remark is about the Comotr engine picture, that’s not the Comotor engine but a NSU RO80 engine !

If you have any questions or requests, please let me know.

regards,

Harald

Thanks for that Harald! I’ll correct the image. We’d love to know more about the Van Veen project!

Dear Paul,

I too was working at Van Veen in the years 1976-1978, and know Harald Westenberger from that period and beyond. While you have indeed captured the main lines, there are perhaps a few more precisions to be made. Only a first try-out prototype had a Moto-Guzzi frame and a Mazda R100 engine. It also had the excentric shaft aligned with the Moto-Guzzi’s drive shaft. The OCR1000 was designed with a completely different setup, and with its own Van Veen designed frame. In about the same period that the OCR1000 was developed, Comotor was looking for additional applications for its expected engine production. That is how the deal between Van Veen and Comotor came about. The Comotor Rotary engines delivered to Van Veen were similar, but not totally identical to the GS Birotor engines. The Comotor twin-rotor engine in your bottom picture is, I believe, a GS-birotor variant as its water cooled trochoid housings differ from those of an NSU Ro 80.

Thanks for that Dick! Wankel motorcycle history is a fascinating and little-told story. I believe ‘Norton Rotaries’ is about the only book on the subject, and doesn’t cover the extensive experimentation going on in every aspect of the motoring industry. The faithful are still working on clean and efficient Wankels, and they remain ideal generator, hybrid, and aircraft engines. David Garside has been working on a Wankel hybrid for some time in his retirement…

Here you find a List of Wankel Licencee`s

https://www.der-wankelmotor.de/Wankelmotor/Lizenznehmer/lizenznehmer.html

Thank you!

Never forget that the commercial displacement of Wankel engines is only that of a single chamber out of the three per rotor, to avoid taxes.

The real displacement is triple.

Do not confuse with the equivalent negotiated 2/3 displacement, to compare with a four stroke classic engine.

Does anyone know where the Wankel Triumph in Hockenheim museum has gone? I am keen to see it but understand it is no longer in the Museum on display at today’s date 26/9/2021. Thanks

I think many of the motorcycles from Hockenheim are moving to the Top Mountain Museum in Austria! More news coming soon…

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this website. Thank you, I will try and check back more often. How often do you update your site?

We post one new film and two new stories every week!