The 1934 BMW ‘R7’ prototype is one of the most talked-about and best-loved motorcycles of the 1930s, yet it never left the factory, and was known only through a single, mysterious photo for over 70 years. The life story of this graceful machine is an untold tale of aesthetic movements, internal factory politics, and harsh commercial realities, in which this lovely motorcycle remained a ghostly ‘might have been’.

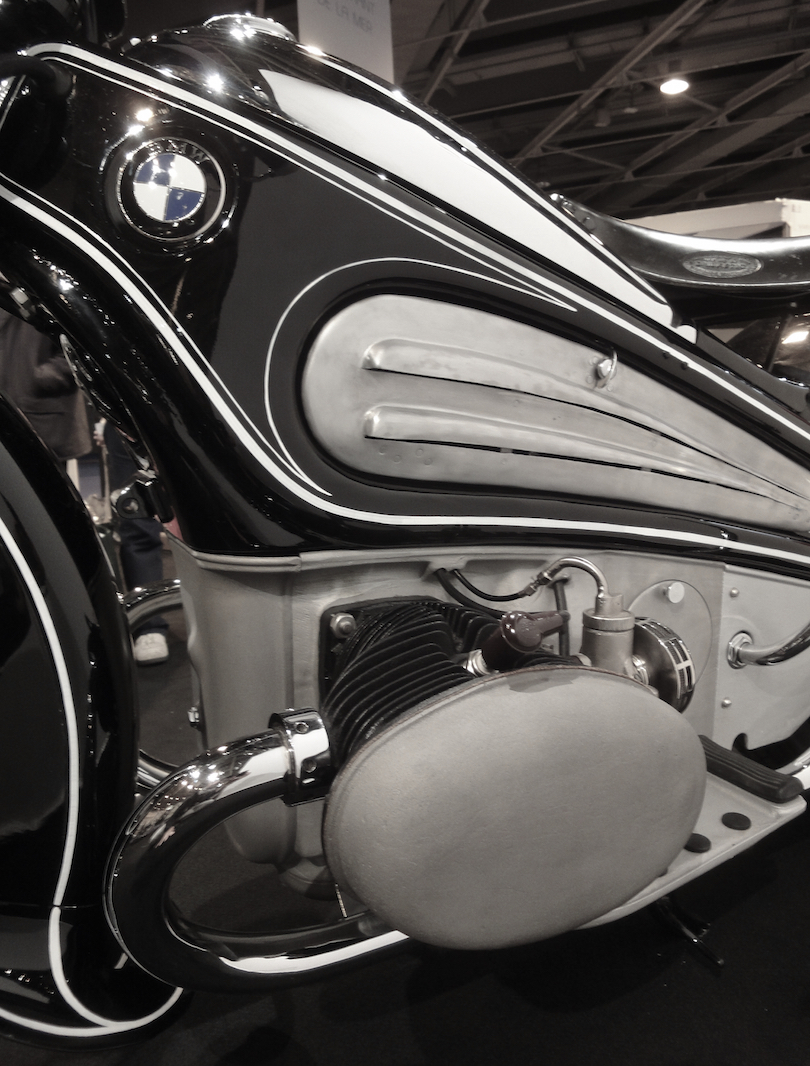

First conceived in 1933, the R7 began with a simple brief; create a wholly new motorcycle as ‘range leader’ to replace the R16, introduced in late 1928. The R16 used a chassis built from stamped-steel pressings (sometimes called the ‘Star’ frame), a cost reducer which eliminated the skilled labor necessary to weld or hearth-braze a tube frame. Previous BMW frames had a Bauhaus simplicity, while the pressed-steel ‘Star’ gained a shapely Art Deco flair. The new look begged an aesthetic question too compelling to ignore, given the general industrial trend towards Streamlined shapes on cars, airplanes, trains, and toasters. If the R16 whispered Art Deco, what would a total embrace look like?

The responsibility for this new machine likely fell to Alfred Böning, the designer of BMW motorcycle chassis from the 1930s onwards. While no names were attached to the curved frame and swooping mudguards of the R7, “it is perfectly clear the hand of an artist was involved”, according to Stefan Knittel, author of several books on BMWs. The prototype R7 is elegant, simple, and perfectly balanced – did Böning unleash a hidden flair for styling, or were BMW automotive ‘fender men’ called in for a bit of curvaceous appeal? In the early 1930s, individual designers were rarely celebrated, although a few ‘stars’ in the industrial design world were rising, like Raymond Loewy and Norman Bel Geddes. BMW first gave kudos to their ‘pencils’ with the 1940 Mille Miglia streamlined racing cars…in the 1980s! No surprise then that so little remains of the R7’s genesis.

While the styling was obviously radical for BMW, the engine and gearbox were equally innovative, a fact discovered only during restoration of the dismantled R7, in 2005. Likely drawn up by Leonhard Ischinger, BMW’s ‘engine man’ in the 1930s-50s, the engine bears a superficial resemblance to the rest of BMW range, but the crankcase and gearbox castings are one-offs, as are their internals. The cylinder heads and barrels are a single casting, as per aero-engine practice at the time; one less joint to leak. The unique crankcase was shaped to seamlessly fit the monococque chassis from which it hangs. The front forks are a BMW first in being fully telescopic, leading the rest of the motorcycle industry by several years. Internally, the camshaft is placed atop the crankshaft, and the gearbox uses a primary shaft separate from the gear cluster, which slows down the gear speed and helps reduce the notorious shaft-drive ‘clunk’ when shifting. These last two ideas appeared in BMW bikes in the 1950s, when Böning was finally able to incorporate them on production machines.

The R7 weighed in at 165kg (5kg lighter than the R16) with engine capacity 793cc, producing 35hp @ 5000rpm (2hp more than the R16), breathing through Amal-Fischer carburetors with accelerator pumps (!) and swill-pots to cure any fuel starvation while cornering. Thus the experimental model had seriously hot performance, being capable of over 90mph while looking sensational. Superbike, anyone?

When completed in 1934, the R7 wasn’t exhibited or press-released; it appears to have been shelved immediately.The first the world knew of the ‘Art Deco’ BMW was a magazine article on the new R5 model in 1936, which included a retouched side-view photo captioned “what could have been”. That solitary photo launched decades of mystique around the R7, giving rise to the Question: why on earth didn’t BMW manufacture this beautiful machine?

Complicated forces worked against the R7. While the prototype is a hand-fabricated one-off, actual production would require huge investment in tooling for the metal pressings, new castings for the engine, gearbox, and cylinders, plus setup for all the unique internal parts. With only a few hundred of their excellent R16 sold, recovering the tooling investment was unlikely. Also, BMW were aware that motorcyclists are very conservative consumers, and bikes which read as ‘design exercises’ in sheet metal were never successful: the Mars (Germany), the Ascot-Pullin (England), and the Majestic (France) all trod a similar path to the R7, being ‘ideal’ designs of innovation and great style, yet doomed to commercial failure. Motorcyclists of the Vintage period, dedicated gearheads all, wanted the fiery beating hearts of their mounts visible in all their complication; this remains our enduring delight.

Internal factory politics certainly played a hand as well. Rudolf Schleicher, chief of motorcycling at BMW, was convinced the ‘range leader’ should be a sporting motorcycle, not a luxury machine, and factory notes indicate his plan for a supercharged motorcycle for the public! The prototype of his blown roadster was seen in the BMW ISDT team of 1935, but such an ‘ultimate motorcycle’ was seriously impractical; “Every owner would need his own specialist mechanic, and BMW didn’t want private competition for their factory racing team,” notes Stefan Knittel. As it was, neither Blown nor Deco was produced, but the telescopic forks and curvaceous mudguards of the R7 did find their way onto the R17 model.

The R7 was dismantled, but never destroyed; it remained at the factory, strapped to a wooden palette in the factory basement, well known to BMW employees. It must have been dear to Alfred Böning’s heart, as he kept it close at hand until his retirement in the 1970s. By this time, BMW was re-collecting its history, with their famous ‘bowl’ museum opening in Munich for the 1972 Olympics. While a clamor arose in the 1980s to revive the R7, it wasn’t until 2005 the task was handed to two legendary restorers; Armin Frey undertook the mechanicals, while Hans Keckeisen massaged the sheet metal. The results are sensational.

The 1934 R7 prototype is an unquestioned design success – a graceful and beautiful study of flowing lines, curves, and feminine masses. Almost to a person, especially to non-motorcyclists, it is considered one of the most beautiful motorcycles ever made. As good as it is, the R7 is a total philosophical departure from what is best about BMW during its first 60 years; restraint. The extravagance expressed by the R7 is shockingly French – more Delahaye than Bauhaus.That the R7 was never serially produced makes complete sense, but 75 years on, she’s still a heartbreaker.

This article was written for the 2011 Amelia Island Concours catalog. Copies of the catalog may be available. Many thanks to Stefan Knittel for his insights and information.

I think while the custom chopper craze was on that such elaborate styling always looked ridiculous; but your “fender men” really pulled it off. Amazing!

This has to be one of the most beautiful motorcycles on Earth. Its spellbinding.

Without doubt the most beautiful BMW and one of the most beautiful of all motorcycles ever created. Nothing, in my simple opinion, matches the design aesthetic of the 1930s. -JZ

Like ‘Playboy’ I just looked at the pic’s.

Frankly I don’t like this motorcycle. It’s form is flowery in a way that seems superfluous to me. I just came in from a ride on my single cyl. modern motorcycle. Each part on the bike tells me what it does and why it is there. The R-7 certainly tells me that it is there.

Like ‘Playboy’ I wouldn’t turn it down (read “kick it out of bed”)but I would rather have my old R-50-warts and all.

Swoopy prewar European bikes are a favorite of mine. There are others but names escape me. Thanks for the post, Paul Venne Thailand/California

I´m not a friend of press steel frames, because they are heavy and not tough enough and because I´m also riding the vintage bikes I can imagine how heavy to handle the bike is. There are also lot of useless decorative material not to enhance riding character but only to enhance the design. I´m more friend of light moderate british design or very early BMW ´s like R 32, 37 or 39. I´m same opinion like great architect from functionalistic era Adolf Loos who in late twenties proclaimed the motto: ornament is a crime!

How come that this wonderful creation is not reach the market? The style is perfect, it was awesome to have a bike like this. Sad to hear that this BMW creation is not appeared in the market.

That is crazy beautiful.

– Dominic E.

That is crazy beautiful.

Susan S.R.

1938 BMW R66 was the most beautiful I think as it was a great rider as well.

John Warren G.

@ John: ah, I know someone who’s ridden the R7, and he says it goes very well indeed!

Wow…that is an amazing looking bike

I love that it is truly a one of a kind. Those fenders are fantastic. Sexy indeed.

Best? Don’t know, but it’s hands-down the coolest! Amazing it was ever built, and doubly amazing it has survived.

Pressed steel construction may be a cost cutting idea but it gives designers freedom to make great looking machines, like the Neander / Opel and this two wheeled sculpture.

This is so beautiful, more style, outrage and engineering than all these hideous ‘creations’ churned out by the modern custom scene; but we know this….

@Chris Daniels, you’re so right. bathos is separated by a qualitative abyss from pathos.

paul-

thanks for posting the r7. i see a lot of chatter about the practicality and usability of such a design. sometimes i think we must take a prototype such as this for what it was, a bold statement of design showing a way forward. in so many ways bmw continues this tradition (albeit sometimes with less style) but it’s these design exercises that ultimately influence the industry as a whole even though they never got off the ground. thanks again mate.

Interesting view on the R7 however not entirely correct, the R7 was lost within the bowels one of the many BMW factory for decades and thought to have been lost forever and only found during a shift from one premises to another.

It is also NOT a shift away from traditional BMW styling it is a masterful development albeit art deco of that very styling. Much more German than French and still 100% BMW.

Credit should also be paid to the many many people involved in the restoration, remanufacture and research that made the R7 possible. The greatest motorcycle EVER.

Interesting; I got my info on the R7 entirely from BMW factory ‘insiders’…

I’m sure more people than Frey and Keckeisen were involved in resurrecting this amazing machine, but those are the names I was given. Everyone indeed deserves credit, the bike is stunning.

I look forward to riding it! Stay tuned!

I think a gentleman in the states was involved too. I’ve seen the bike in person. it is really spectacular.

This is an incredible bmw. I would love to take this puppy out for a ride. What do they run?

Great bike, great article.

Just one correction: The Danish Nimbus ohc four used a telescopic front fork on their production bikes from 1934 onwards, beating BMW’s production bikes by one year. Nimbus prototypes with the modern front end were tested years before it was offered to the public, but then another manufacturer might have beaten both Nimbus and BMW to have used the idea just experimentally.

I rebuilt and run 3 ( /7s and a K ) BMWs and am working on a 4th ( /7 ).

I dislike to burst peoples’ bubbles, but I don’t particularly like it, too enclosed and unknown, and the kickstart sticks out like an afterthought. In addition, I believe that the camshaft is under the crank, not above as the article says because there are no pushrod tubes to be seen, and I don’t believe that BMW would have drilled pushrod tubes into the barrels back in 1934.

Ars Gratia Artis; Compliments to the publisher who found

this deep in Munich. Art Deco styling never loses its appeal,

especially in a one-off. For aficionados of Brough-Black Prince

Vincents,

as the early Broughs were to TE Lawrence, BMW had an answer

unique.

I have just restored a 1951 BMW R 51/3, while a 62 R 69 S

stared at

the restoration process. Motorcycles are still like

beautiful women:

the eye of the beholder determines whether to indulge, mount-

or just gaze fondly from a distance. An R-68 with a companion

on the loaf seat….?

This bike is a piece of art! If it was in production I would definitely purchase it