One-piece utility outfits first appeared in the mid 1800s, as ‘boilersuits’ for crawling into the firebox of coal-burning steam vessels for cleaning, where a gap between jacket and pants could catch on the tight hatch of the ‘firehole’ (where coal is shoveled into the burner). Further uses were soon found for the boiler suit, especially where dust, rain, or cold could enter a vulnerable gap at the waist. By the turn of the 20th century, some industrial manufacturers required one-piece suits at work, and the boiler suit came to be seen as a symbol of industrial progress.

It was Adolf Loos – architect, acerbic journalist, enemy of Decoration – who first declared the one-piece industrial suit as the ideal expression of Modern dress, devoid of superfluous frills. The utter lack of fashion potential was perfection for Loos, who railed against all decorative flourishes in architecture, penning the seminal essay ‘Ornament and Crime’ in 1908, seeing simplicity and ‘clean’ design as an almost Moral necessity. The only way humanity could save itself from destruction, he felt, was to embrace an aesthetic freed from cultural baggage, and move forward into a modern era…in coveralls.

Irascible Adolf Loos had a profound impact among Modern architects and Utopian thinkers, and the one-piece suit became the cliché uniform of the modern worker-citizen. In support of the Soviet ‘experiment’, Constructivist artists Alexander Rodchenko and Vladimir Tatlin each designed coveralls by 1921, to be worn by all Soviet workers. At the same time, Le Corbusier wore workers’ coveralls as an expression of his Utopian theory of the mechanization of modern life, with houses as ‘machines for living’, adoration of Henry Ford’s mass-production techniques, and belief that assembly lines and industrialization were the model for humanity’s salvation from itself. Many Bauhaus artists and thinkers were similarly drawn to the one-piece suit, for the same idealistic reasons.

Other artists, such as Fritz Lang in his remarkable 1926 film ‘Metropolis’, saw the industrial worker’s suit as the very symbol of a Dystopian future, reducing people to replaceable mechanical automatons and neglecting the messy beautiful heart of humanity. And indeed, by the 1930s, the icons of the Modernists had lost their lustre; the Soviet Union had devolved into Stalinist totalitarianism (imprisoning avant-garde artists and intellectuals), while Henry Ford gave hundreds of thousands of dollars to Adolf Hitler, who had a very different uniform in mind for Germany.

But none of this was the fault of the boiler suit! The usefulness of having no gap between trousers and jacket became apparent for different applications; rainproofing and warmth. During WW1, pilots of open-cockpit biplanes needed protection to fly in inclement weather, which inspired Sydney Cotton to invent the one-piece ‘Sidcot’ flight suit, in 1917:

“In the winter of 1916, several members of his squadron returned from a mission practically frozen. Sidney Cotton, however, was not troubled by the cold, a fact which he attributed to his oily overalls which he did not have time to change out of in the scramble to get airborne. He concluded that the oil sealed the fabric and trapped a layer of warm air next to the body. He had his tailor make up a special suit of a light Burberry material [waterproof cotton gabardine] with a lining of thin fur and air-proof silk together with fur cuffs and neck. He registered his design as the “Sidcot Suit” which was worn extensively thereafter [until 1950 in the RAF]…when Manfred von Richthofen was shot down, he was found to be wearing a suit of similar design.” (‘Aviator Extraordinary’, Barker, 1969)

Coveralls were also worn by early automobilists and motorcyclists, typically to protect streetwear beneath. These were invariably made of cotton, sometimes waxed, and appeared in motorized transport by 1900, a very dusty period with unpaved roads and open vehicles. As cars became enclosed by the 1920s, they shed specialized clothing, but motorcyclists continued their exposure to the elements, and coveralls of various types are still popular, now called ‘riding suits’.

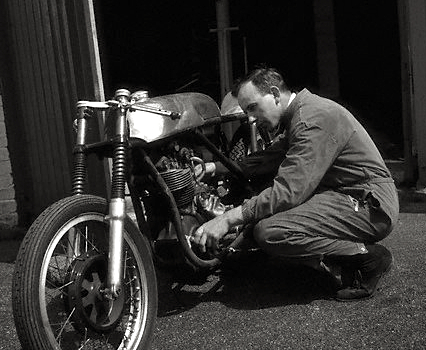

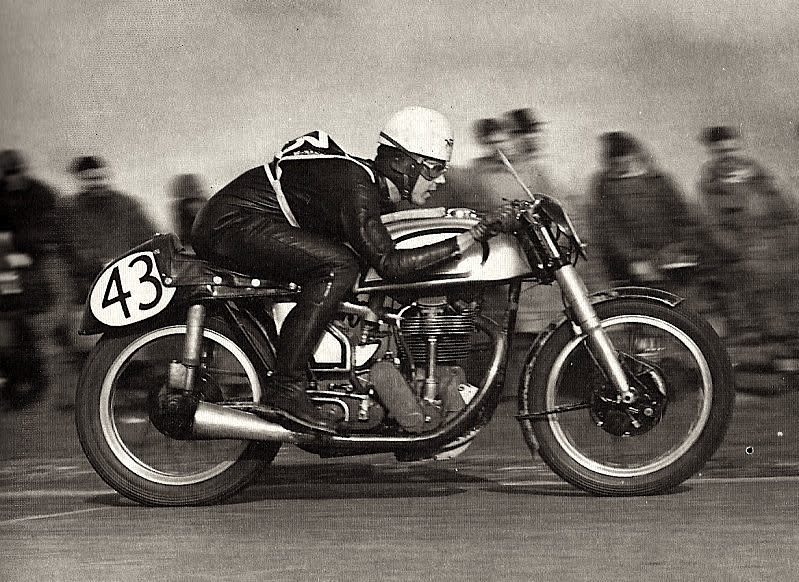

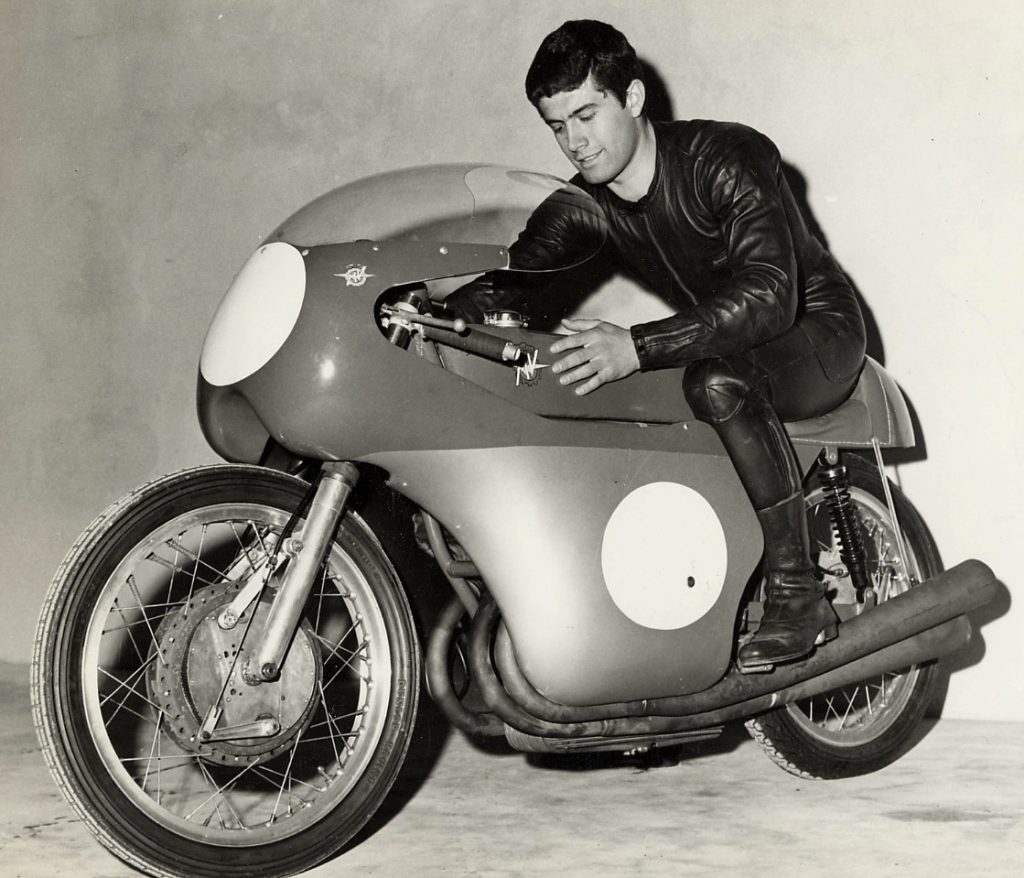

Racing a motorcycle requires a more stubborn material than waxed cotton, and the leather one-piece racing suit was allegedly invented by six-time World Champion Geoff Duke in 1950, when he instructed his tailor to wrap his body in form-fitting leather. Duke reckoned the baggy two-piece ‘Brooklands’ racing outfits worn by professional bike racers since the 1920s were causing all sorts of aerodynamic drag, and he was right. Riding his Norton against the technically superior European 4-cylinder machines, Duke’s riding skill and the visual appeal of his tight black outfit made him a huge star in the popular press, and ladies swooned for him as they would for a movie star. The form-fitting one-piece leather suit very soon became, and remains, the only legitimate motorcycle track-racing outfit.

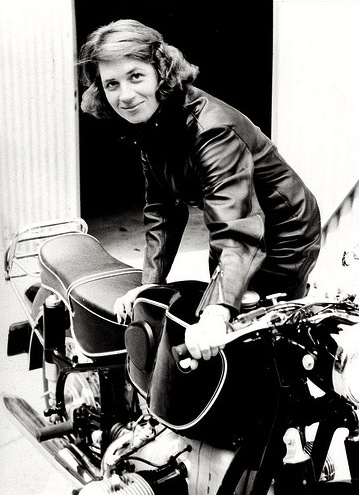

Another pioneer of the leather racing suit, for women in love with speed and motorcycles, was Anke-Eve Goldmann, the stylish and talented moto-hearthrob of 1950s Germany. As one of a rare cadre of women racers, AEG wanted the same advantages as Geoff Duke, and designed her own form-fitting one-piece leather racing suit to be made by Harro, with modifications accommodating her feminine figure – the obvious tailoring changes, plus a diagonal zipper across the chest. Anke-Eve, initially reviled in 1950s Germany for daring to be herself, soon gained respect of motorcyclists around the world with her journalism (published as far afield as the US and Japan) and riding skill. Typical for women at the time, she was barred from official road-racing competition (except ‘ladies races’, which she always won), but she wore her svelte leather racing gear on the roads of Europe in all weathers, including the Elephant Rally in mid-winter Germany, many times.

Anke-Eve, a highly visible and charismatic person, drew the attention of writer André Pieyre de Mandiargues, who befriended and corresponded with her. The central character of his book ‘The Motorcycle’ (1963) was clearly based on a fantasy of Ms Goldmann, as ‘Rebecca’ rides her Harley-Davidson across Switzerland, naked under her black leather one-piece riding suit, to meet her paramour in Heidelberg.

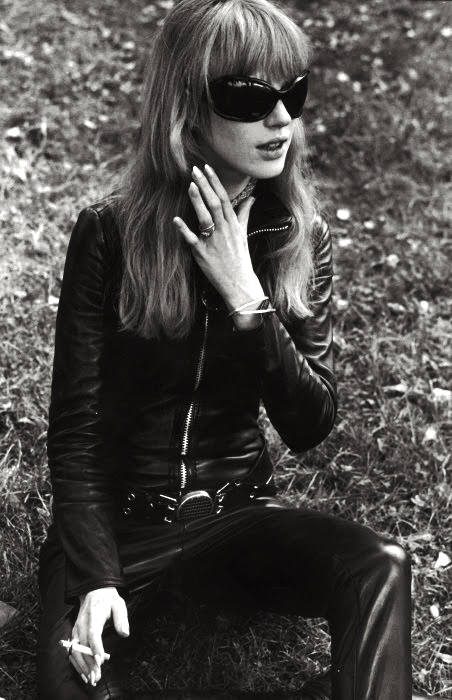

De Mandiargues’ book was made into the 1968 film ‘Girl on a Motorcycle’, starring a very young Marianne Faithfull as a speed-mad vixen, riding ‘naked under leather’ (the European title), fantasizing about her lover while masturbating on the vibratory saddle nose of her Harley, dying at the climax. (Intriguingly, Marianne Faithfull is the Baroness Sacher-Masoch, and her great uncle Leopold von Sacher-Masoch will be remembered eternally for writing ‘Venus in Furs’, the source of the term Masochist) A serious woman like Anke-Eve Goldmann, attempting to gain respect as a rider, journalist, and feminist, was not impressed with the fetishization of her riding attire.

But long before Marianne Faithfull donned her fur-lined leather suit on film, Diana Rigg zipped into her own skintight outfit in The Avengers television series, making Emma Peel a crime-fighting fetish goddess in 1961, the show understandably becoming the longest-running TV serial for decades. Emma Peel’s outfit was an obvious nod towards comic book heroines…

Being tall, blonde, and beautiful in a tight-fitting leather suit had been the stuff of men’s dreams for 15 years before AEG donned her custom riding gear, and 20 years before Emma Peel high-heel kicked baddies to the floor. In the comics, the Cat (later Catwoman) began to sexually vex the hugely popular Batman as early as 1940, wearing what became the ‘catsuit’. Muscular men in skintight outfits had been around only a few years more, Superman having flown into pulp by 1938.

By 1966, Catwoman leapt from pulp to screen, purring her way to Batman’s heart in the wonderfully camp television series, actress Julie Newmar making her own best possible catsuit from Lurex, not leather. The magic of her one-piece, just as with Mrs. Peel, conjured visions of feminine dominance and aggressive sexuality, even among innocent young boys (like myself) who had never laid eyes on fetish porn. Everyone, male and female, felt instantly the switch of electric current generated by a confident woman in a black leather bodysuit; while male heroes in similar outfits evoke strength, physicality, and danger, a woman clad thus is a total inversion of traditional sex roles, poking a gloved finger into some ancient part of men’s brains, driving them absolutely nuts with desire.

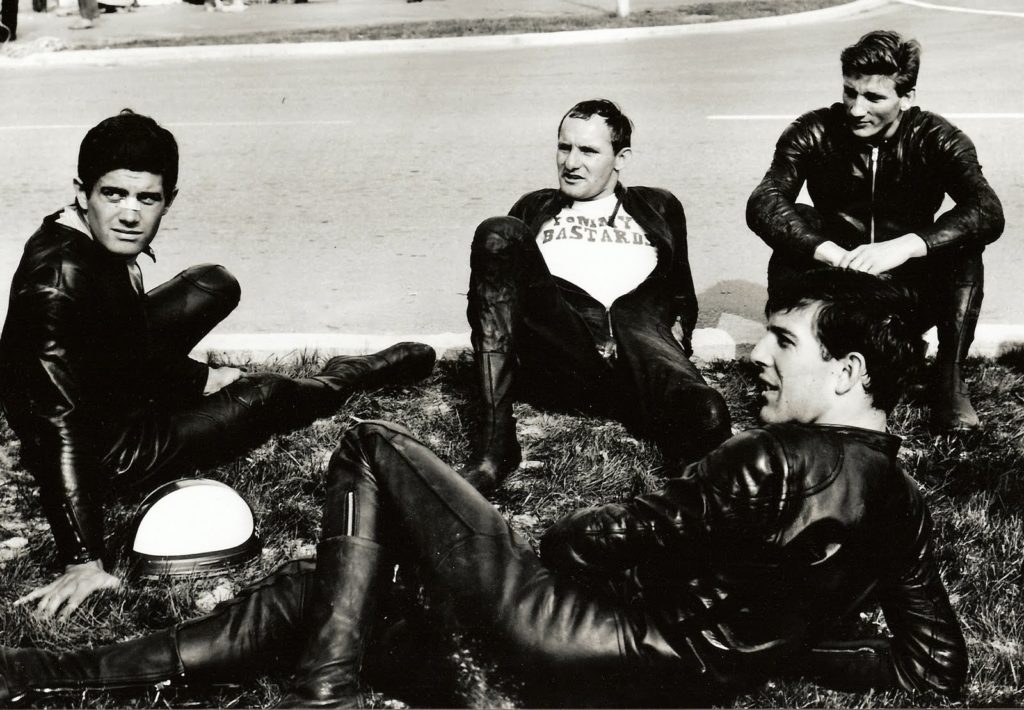

The parallel worlds of fantasy and reality met in the persons of Anke-Eve Goldman and the road-racing men of the 1950s and 60s, who all gained a spark of superhero magic in their sleek black outfits, hammering out epic battles while crouched on howling machines. Not surprisingly, motorcycle racers became sex symbols at the same time they slipped into a second skin, and Geoff Duke yielded to youngsters Mike Hailwood and Giacomo Agostini, the real-life hot young Supermen of the 1960s.

And while Superheros caught the public’s imagination, it was Motorcycling heroes who wore ‘the suit’ in real life.

Well penned, PdO! That final photo in the list, of Ago, Hailwood, Read and Ivy is one of my all time favorite vintage shots of these legendary racers in full leathers (love Hailwood’s shirt). Just chillin’ on a patch of grass by the road. Be still your beating hearts, ladies ; )

Hi Paul,

Love your passion for all things and stories related to vintage motorcycles!

Just a minor observation, I believe the tank on Ms Goldmann’s R69 is a Hoske tank.

Have the same one on my 1960 R69 with the Hoske seat…

Always look forward to your next posting.

Thank you

Glad to show the historical genesis of these sexy , male jumpsuits as our own masculine fashion before covetous females ” steal ” this garment for themselves and become 100 % feminized never to be return to a masculine clothes closet again; gender Marxist bigotry.

I tried laytex but just stuck and bounced when I took a spill on my R69S

my riding suit wasn’t near so sexy-more like a zip on sleeping bag! if i rode in the rain(i did,a bike being my only transpo) is would get soaked if not enough 3M were applied….

Fascinating history. Did not know that Rodchenko had designed his own jumpsuit. Very cool.

Dear Paul

Nice article funny the only one we never made a replica lid was Bill Ivy but I do have a book about him quite a wild character from what I remember.

Fid

Vince Austin wears coveralls all the time. He’s a trip, a funny adventure rider, film maker and bon vivant

Hi Paul,

Interesting to see the flying suits . In the 1950s a teenage Brian Verrall dressed his younger brother in an electrically heated RAF flying suit.

Plugged him in and discovered quite quickly it was designed for 24 volts, not 240 volts mains! The smoke was a give away.

Still, great way to warm up your relatives!

Happy New Year,

Cheers,

Ian.

Heated indeed! 😉