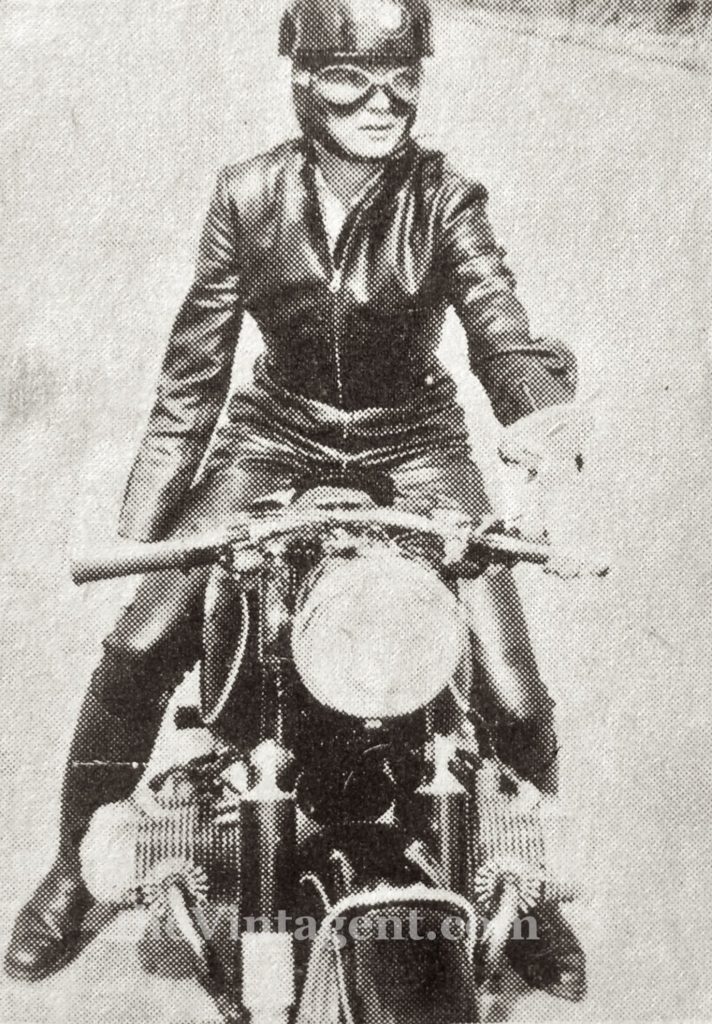

The tides of her acceptance in German society began to change when Goldmann started writing for motorcycle magazines around the world: Cycle World, Moto Revue, and Motorrad among others, documenting of her experience riding the Nurburgring, plus European race reports, etc. Her most intriguing article documents an all-but forgotten chapter in Soviet sports history: the Women’s motorcycle racing circuit of the 1950s/60s. For a West German woman to document Soviet motorsport in 1962, while the Berlin Wall was being built, was a shockingly defiant act. As a result, this article never appeared in any European magazine, and only Cycle World in the USA published the story, as the bleak tensions of the Cold War ramped up dramatically, with Berlin as the focal point of a possible nuclear war between superpowers.

But Goldmann had no such political agenda; she wasn’t a closet Socialist with Soviet sympathies, but was, rather, a feminist before that label was popularized. Her experience of being shut out of racing tracks because of her sex rankled as an injustice, as was the ridicule she experienced for daring to be a woman on a fast motorcycle, able to handle herself and her machine with ‘masculine’ aplomb. AEG, who helped found the Women’s International Motorcyclists Association (WIMA) in Europe in the late 1950s, was the first and only Western journalist to document Soviet women’s racing, with no need to comment on the irony of women being ‘free’ to race motorcycles in the Soviet Union, while she in the ‘free’ West was not.

Goldmann had arranged in 1961 to visit the Soviet Union as a journalist to document women’s motorcycle racing, but a visit from the American CIA (an attempt to recruit her as a spy) horrified her, and she cancelled the trip. Instead, AEG built up a correspondence with the Soviet women she documented, and relied on them to supply photographs and race results, plus the names of the riders with a few details, like their hair color…the habits of a patriarchal viewpoint die hard, and while Goldmann never referred to Mike Hailwood as ‘blonde’ vs. a ‘gorgeous’ Giacomo Agostini, she includes such notes as a way of distinguishing the characters in her report, which must reflect on the extremely limited information available to her…although it does add charm to the story.

Sadly, her Soviet correspondence and all related photographs were collected in an album which disappeared from her family’s Swiss summer chalet in the 1970s, and this article is what remains of this unique period in motorcycling history. Here’s the article in its entirety, reprinted from the October 1962 edition of Cycle World magazine:

SOVIET ROAD RACING CHAMPIONSHIPS FOR WOMEN

By Anke-Eve Goldmann

“How many motorcyclists in the Western world – male or female – are aware of the fact that in the Soviet Union women are enjoying their own road racing championships? While England is already exceptional in dauntless girls on short circuits, there are hundreds of female road racers competing regularly in Soviet Russia.

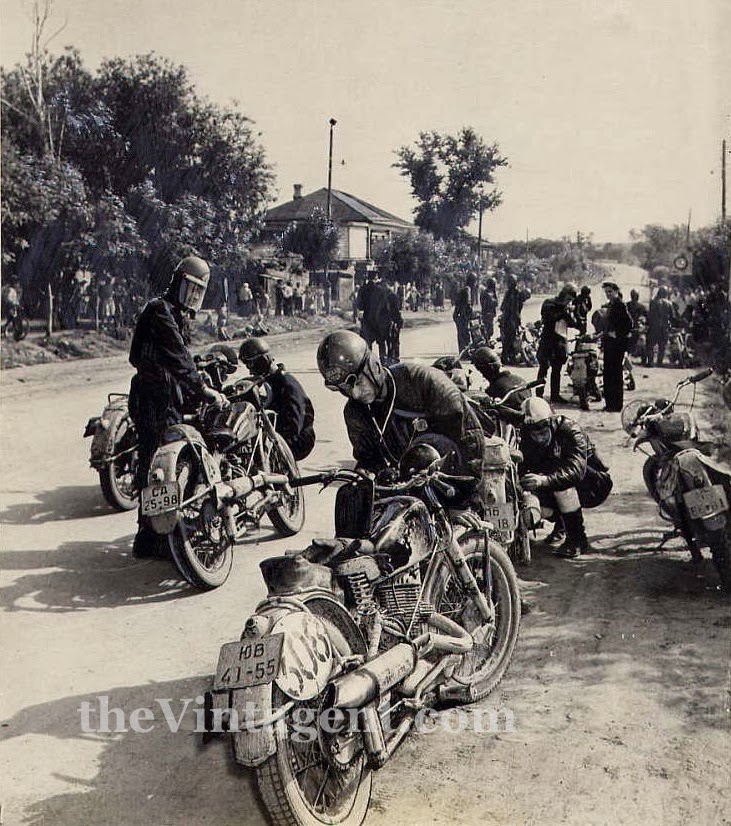

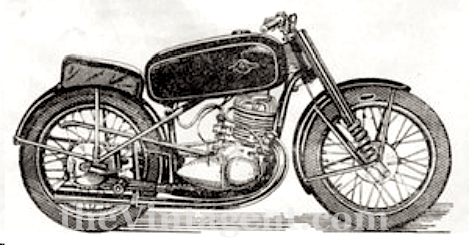

And the most enviable thing is that they have their own championship races. The first of them was held in 1949 on the lovely, 6.746km (4.189mile) road circuit at Pirita-Koze-Kloostrimetsa, near Tallinn, in Esthonia. For reasons unknown, that small country is the center of Soviet motorcycle racing. Naturally, no highly specialized racing mounts were ridden in that first meeting. The 125cc K-125, and the 350cc ISH-50 and IZH-54 two-strokes (very much DKW-looking), which developed about 7.5 and 14.5hp respectively, had solid frames and girder forks.Prytkova won the historical 125 races over 15 laps at a speed of 80.5kph (49.99mph), with veteran Lydia Jefremova second[was she a war or racing veteran? – pd’o]. Most girls lapped at below 70kph (43.47mph), and the best male rider at 86.76 (53.87mph). Irina Ozolina, of Moscow, won the 350 class at 89.76kph (55.74mph), ahead of Lydia Tratsevskaya.

Next year’s 125 winner, Nina Mikhejeva, was faster than the best male had been in 1949. That strong, blue-eyed girl who took 7th place in 1949, won both race and championship at a speed of 86.6kph (53.77mph) and a record lap of 91.2 (56.63mph). With Nina, the most prominent of Soviet girl racers had entered the scene. Indefatigable, of great physical strength, and entirely fearless, this woman conceals high personal charm under very determined looks. Second place went to Armenian Tumanjam at 84.84kph (52.68mph), who V.Morosova, T. Trossi and Esthonian N. Ratasepp filled the next places. Irina Ozolina again won the 350 event, this time at 91.62kph (56.89mph) with a fastest lap of 93.3 (57.93mph). Lydia Tratsevskaya finished second.

In 1951 Nina Mikhejeva (whose name was now Susova)[recently married? – pd’o] shattered all records, riding her 125 faster than the male winner of the year before. She averaged 90.46kph (56.17mph) and pushed the lap record to 93.41 (58mph) in the 125 division, out-racing V. Morosova and L. Sviridova. A lovely girl came in fourth – Virve Gustel, of a famous Esthonian racing dynasty [Estonian readers – please clarify? – pd’o]. Tumanjan and Ratasepp did not finish. The 350 event was won, not by Irina Ozolina, but by T. Trossi who, taking things easy, rode to a safe win at 89.29kph (55.46mph). That miss Trossi can ride is shown by her lap record of 93.77 (58.23mph) established when Irina was still in the race. N.Nosenko beat Virve’s sister, Ylme Gustel, for second place.

In 1952, both Nina Susova and Irina Ozolina returned to Moscow with their third championships secured. Nina, in top form, smashed all opposition. Though unchallenged, she took the checkered flag after 1 hour, 5 minutes, 2.3 seconds for a 93.35kph (57.97mph) average. A new lap record of 4.15minutes and 95.24kph (59.14mph) also went to her credit. Second place was taken by V. Morosova, who had been lapped by the dashing Nina. Mis Reichenbach finished third. The 350 race was won by Irina Ozolina at 96.01kph (60.62mph) and the lap record now stood at 98.72kph (61.30mph). Runner-up was Ylme Gustel; V. Petrova wound up third.

1953 became the year of the sisters Gustel. Nina Susova was out of the race on the first lap, and lovely Virve defended her first place successfully, averaging 89.02kph (52.28mph). Fastest lap in that race, at 93.18khp (57.86mph), was ridden by V. Morosova who, after a long stop in the third lap, hurtled through the whole field and finally beat Esthonian N. Ratasepp by a narrow margin for second place. Virve’s sister Ylme was the winner of the 350cc class after Mrs. Ozolina had engine troubles. Ylme pushed the 350 record up to 97.56kph (60.58mph) and rode to a splendid 350 lap record of 99.67kph (61.89mph). Esthonian Tea Tahk grasped second place, in front o f N. Nosenko. Helju Kuunemae, bearer of a famous name in Soviet racing [more please! – pd’o], went out of the race with engine bothers for the fourth consecutive year.

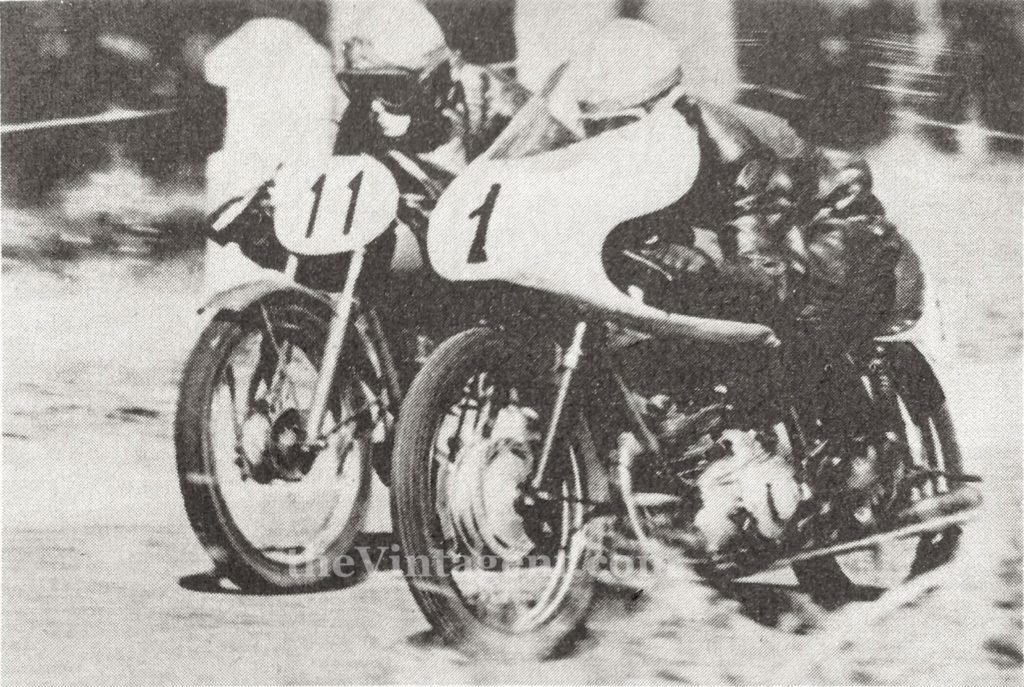

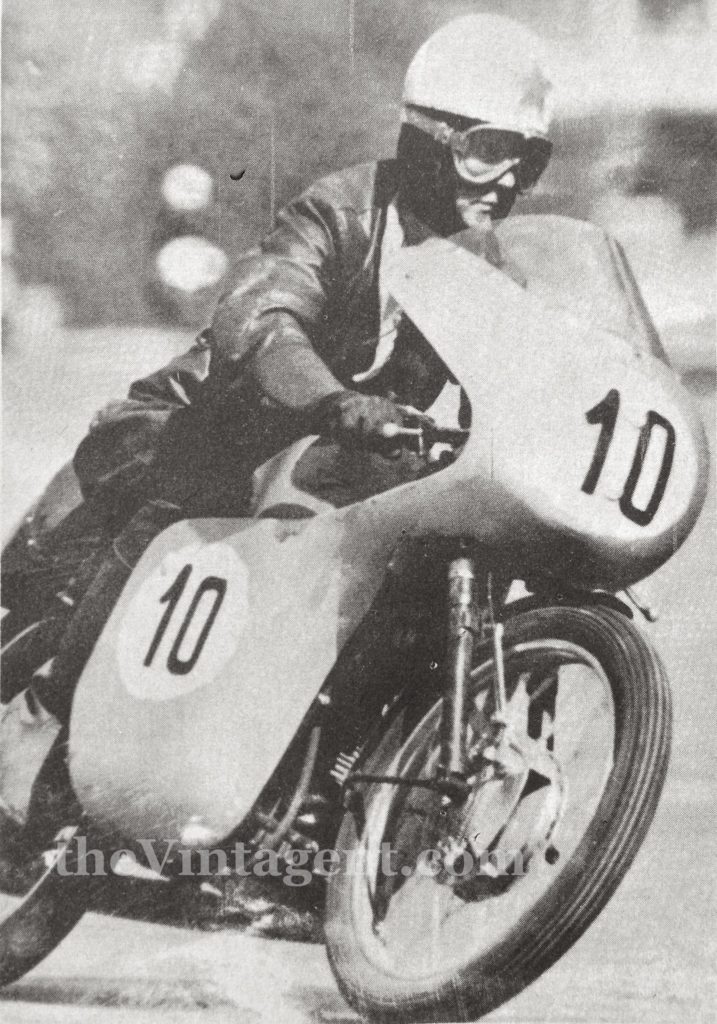

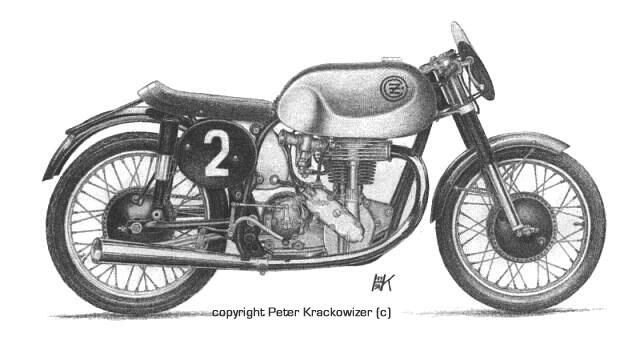

For 1954, the 350 class was abandoned. All girls now competed in the smaller class, and Irina Ozolina won the championship with a speed of 90.91kph (56.45mph) over Nina Susova and I. Tomin. In these years other changes also took place. Different road circuits had been prepared, and the best racers now made use of a new model, the S-157, a twin OHC single-cylinder affair, giving 14.5bhp and built on the lines of the Czech CZ racer. Fairing made their appearance, and the Russian girls met female road racers from other Communist countries, notably Hungary.

In 1955 Nina Susova struck back an won that year’s championship, beating Irina Ozolina and Esthonian Evi Nugis, a beautiful fair-haired newcomer who was to become one of the most prominent racers of her country. After the 1956 championship had again been swept by Nina Susova, Evi obtained top honors in 1957, establishing a scintillating new record of 97.16kph (60.33mph) and also a lap record of 99.02 (61.49mph).

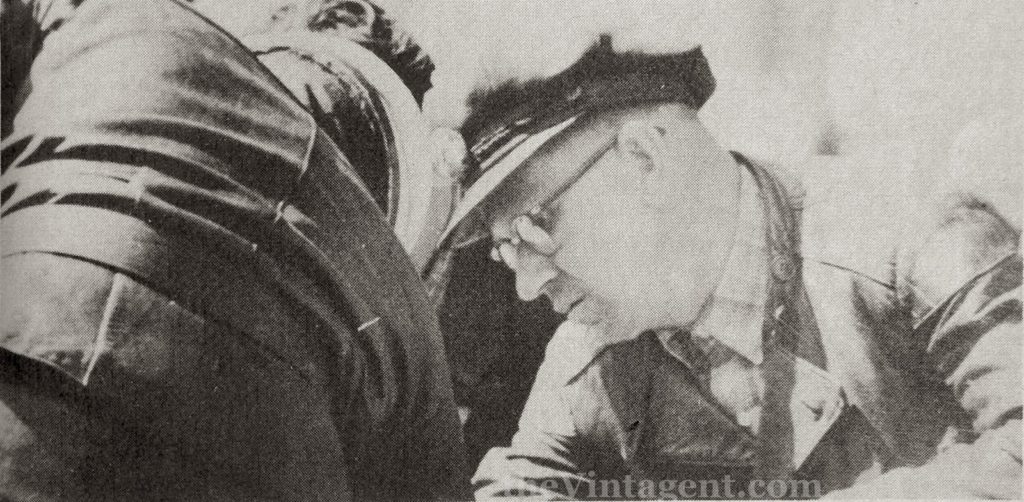

The championship was decided by two races for the first time in 1958 – at Leningrad an at Talllinn. The first heat was won by the indestrcutible Mrs Ozolina on her S-157 over blonde Evi Nugis and veteran Tratsevskaya. In the second race, Evi had trouble, so Irina was content to secure a second place behind Nina Susova which was all she needed to take the 1958 crown. Incidentally, no one knows for sure just how old Irina is, but she started motorcycling in 1939, and is now well over 40!

Three races counted for the 1959 championship – Riga, Tartu, and Tallinn. Nina had given up racing so it became a year for the ‘old lady’ again. At Riga, Irina managed to beat V. Petrova and local star Vilma Oshinja; at Tartu she was chased in determined manner by an unknown 20-year-old girl from Esthonia, Evi Freiwald, who also gave her a breathtaking fight in the third race, at Tallinn. Mrs. Ozolina won, but she had to try all she knew to keep Evi from winning – a girl who was born after Irina had already started to ride motorcycles!

The 1960 championship consisted of two heats: Tartu and Tallinn. The Tartu even was a terrific struggle. The winner was – well, who? – Irina Ozolina, who propelled her S-157 around the circuit at an average of 101.27kph (62.88mph). The lap record, however, was established by Visma Lapinja on an East German MZ at 109.57kph (68.04mph)! Visma took second place in the race at a speed of 100.15kph (62.19mph). Tea Tahk, on another S-157, was third. Evi Friewald had engine troubles. The Tallinn heat was won by Irina, too, at 93.97kph (59.88mph), while Latvian Erika Kiope beat Vilma Oshinja for their berth.

In 1961 several major changes were observed, the most notable being a ban on specialized racing mounts. This decision was taken to level the chances, and meant that star riders no longer were assured the fastest machines. 1961 was also notable in that it brought the ‘Ozolina monopoly’ to an end. Irina was defeated by Latvian racers. At Tartu, Vilma Oshinja seemed a safe winner when, in the last lap, Erika Kiope made a determined effort and won by a few yards. At Talinn, Irina tried to rescue her championship chances and gave Vilma a sparkling fight for victory, but Vilma won the race and the 1961 championship.

I do not know how the Soviet girls would look in races in Western countries. Without doubt their courage is comparable to the fearlessness displayed by Soviet International 6 Days Trial riders, but I think that their riding style and racing experience still lacks perfection. If given International racing experience the Soviet girls certainly could become racing competitors to be reckoned with, and I would give all the tea in China to see them race against this year’s 50cc Isle of Man competitor Beryl Swain, and that dashing Californian, Mary McGee.”

The S-157 racer was a DOHC single-cylinder based on the CZ. Here’s what Mick Walker had to say in his ‘European Racing Motorcycles’ book: “The next Soviet racer was the S-157A, an interesting lightweight for the 125cc class. This was a dohc single with valves set at an angle of 50 degrees, measuring 28mm exhaust and 32mm inlet. The stroke was rather long at 58.5mm which with a 46mm bore gave a cylinder capacity of 123.6cc. When FIM President, Peit Nortier, visited the Central Automoclub headquarters in Moscow during 1959, the chief of the technical department told him that it was not intended to put the S-157-A up to the challenge the top Italian lightweights, rather to provide a production racer; and to this purpose a batch of 25 would be constructed toward the end of that year.” Walker added he didn’t think the S-157 was actually built, but he’d never read AEG’s account from 1962!]

Goldman is often a Jewish surname. Although in her case she would have had a hard time surviving the holocaust given where and when she was born. If she were born into a Jewish family it would add a whole additional dimension to her amazing life.

Great research you guys.

Jerry, here’s a tidbit from an interview I conducted with AEG’s former husband, Hans, who had Jewish family: “AEG had a Jewish name but was Aryan. Her family was opposed to me, as a ‘mitzlinger’ – such families were executed from the mid-30s onwards. It started with half-breeds who were married to Jews. In mid-1944 the half breeds with German husbands started to be hunted. My father was such, but was allowed to work in a factory with a salary. I had 5 years in the Hitler Jugend. I went painfully every weekend and hated it, but it was politically necessary. I was offered a position as an officer in the HJ, but declined. We had friends who were officers in a Christian political party; after he was kicked out of office, he worked at the telegraph, sorting addresses. When the Gestapo telegraphed information, he warned my father. That’s how he survived the War.”