Tension between radical Jacobins and moderate aristocrats, both seekers of change, became increasingly focused on class distinction, and many nobles lost the titular d’ or du or de appending their surname, bowing to the fashion for ‘egalité’, and an increasingly hostile atmosphere towards inherited titles. For Pierre Samuel, his physical defense of King Louis and Marie Antoinette from a bloodthirsty mob in 1792 culminated in imprisonment by 1794, which meant the guillotine for any aristocrat, and thousands of others put to a defense-less trial, or no trial at all. But, as ‘revolutions eat their heroes’, the beheading of Maximilian Robespierre later that year meant du Pont and his family survived, but the continuing political and economic turmoil of the Directoire period (1795-99), plus the sacking of their home by a mob, saw the du Ponts sailing for America in 1799.

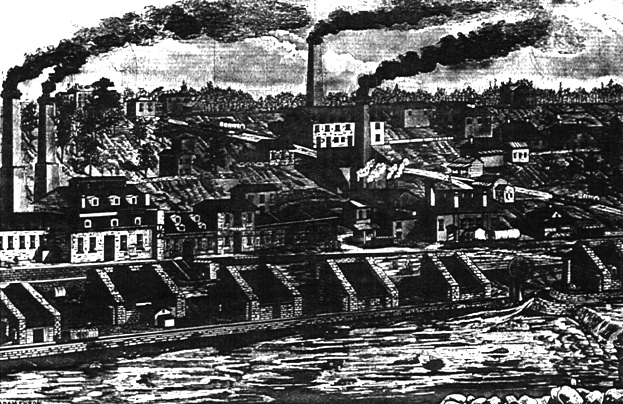

Éleuthére had worked with the renowned French chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (before he was condemned with “The Republic needs neither scientists nor chemists”, and beheaded in 1794) at the Paris Arsenal, gaining expertise in gunpowder and nitrate extraction/manufacture, which would play a huge role in the family’s development of nitrocellulose lacquers, and ‘smokeless’ gunpowder, in the US. The family intended to create a French cultural community in Maine, but a hunting trip with a US military gunpowder procurer (and former French officer, Louis de Tousard) demonstrated the inferior quality of American black powder. Éleuthére’s expertise in the manufacture of gunpowder led the family to invest heavily ($84,000 in 1802) in the creation of E.I.du Pont de Nemours and Co., or simply DuPont, in the Brandywine Valley of Delaware.

Subsequent generations of du Ponts arranged inter-marriage to cousins, keeping their rapidly expanding wealth, and family control of their business, close at hand. The Du Pont corporation grew into the world’s third largest chemical company, inventing things like nylon and kevlar and neoprene. As their wealth exploded, du Pont family members invested in many other areas, including, for a time, automobile (Pierre du Pont was president of General Motors in 1920) and motorcycle manufacture.

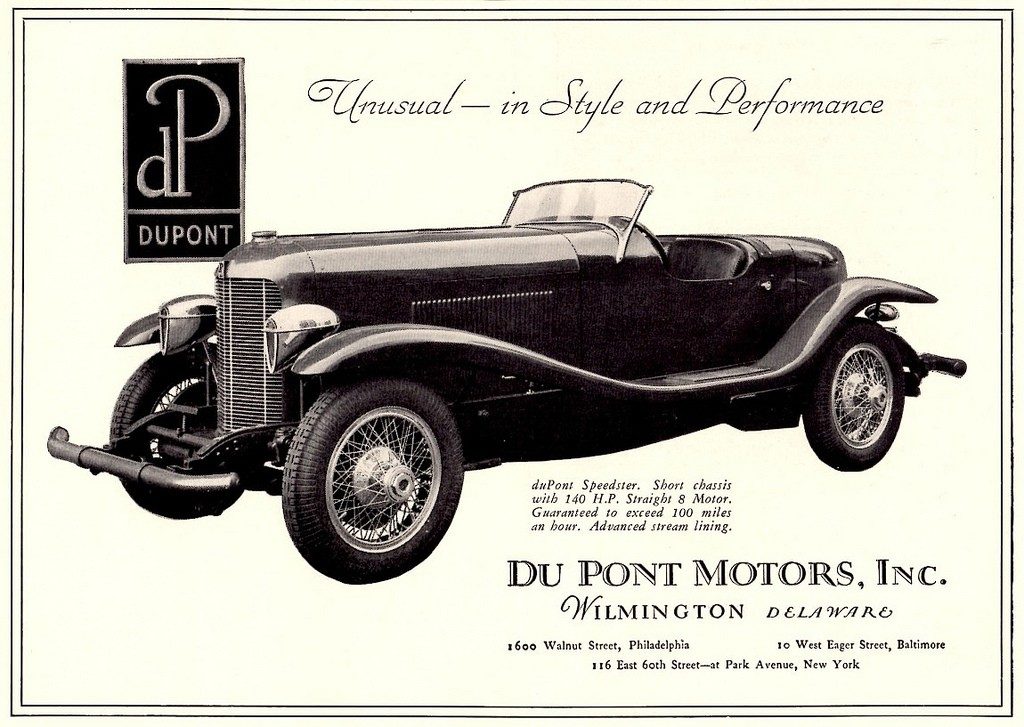

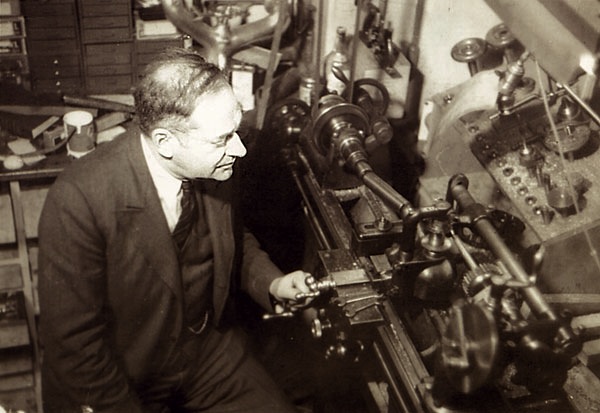

The family dabbled in making DuPont automobiles of their own starting in 1919, when E.Paul du Pont, a lifelong tinkerer and ‘gearhead’, grew from making marine engines for the US WW1 effort, to full automobiles. As only around 600 DuPonts were made in the 12 years of the company’s existence, it was clearly never going to be an enormous success, especially after the stock market crash of 1929. E.Paul’s brother Frances had invested $300,000 (in 1923) in the Hendee Mf’g Co., makers of Indian motocycles, and Indian’s near-bankruptcy in 1930 meant the family was likely to lose a substantial investment. E.Paul merged DuPont Motors with Hendee in 1930, deciding in ’31 to drop autos completely, and concentrate on making Indians.

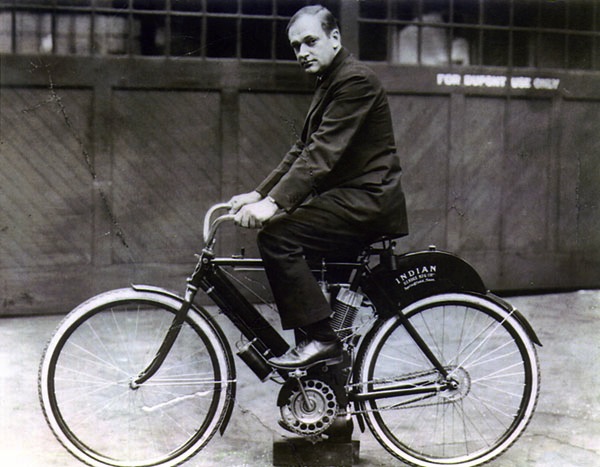

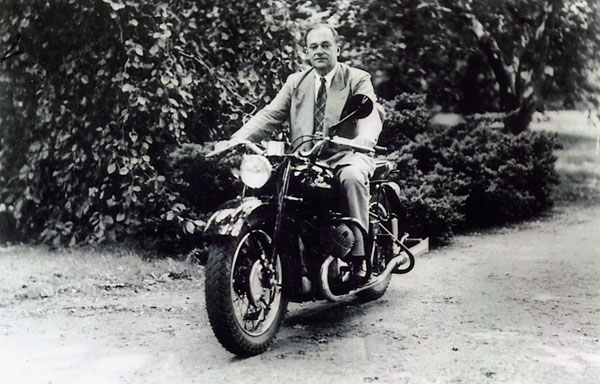

As the new president of Indian, E.Paul made significant changes; as a lifelong motorcyclist (having built his first clip-on moped as a teen, then owned an early Indian ‘Camelback’), he felt the days of motorcycles as utilitarian vehicles were over, and embraced the idea of a motorcycle as ‘leisure object’.

To support this view, the company focused on three areas: the new production-based ‘Class C’ racing in the US, the DuPont Company’s huge automotive paint color palette, and the styling of Briggs Weaver. DuPont pioneered fast-drying nitrocellulose lacquer auto paint in the early 1920s, and suddenly brilliant colors were no longer a hindrance to manufacture, as previously only black paint would dry quickly enough for economical manufacture (Henry Ford’s famous ‘any color as long as it’s black’ was a practical dictum – only black paint dried quickly). Thus, Indian motocycles were shortly available in 24 different, brilliant colors, while their sheet metal grew more elaborate and Art Deco-inspired, and their racing team grew increasingly successful (E.Paul’s son Steven was an engineer and helped developed the ‘Big Base’ racing Scout).

By 1938, Indian had gone from losing hundreds of thousand of dollars per year, to amassing huge profits with their beautiful and iconic motorcycles – the Chief and Scout. Briggs Weaver’s styling of these models remains emblematic of Indian’s identity; the deeply skirted Deco fenders and Indian-head motifs are still our first image of Indians today, and the brand identity of every subsequent revival of the Indian marque in modern times. As WW2 approached, riders smelling an upcoming war bought out the company’s production, before civilian production stopped, and the factory concentrated on building motorcycles for the US military. The immediate pre-war period was the peak of Indian’s profitability, but E.Paul Du Pont’s health was declining, and the profitable Indian factory was very attractive to investors. In 1945 Indian was sold to an investment group headed by Ralph B. Rogers.

Related Posts

July 8, 2017

The Vintagent Trailers: Mancini, The Motorcycle Wizard

The mechanic that helped debut five of…

Hello Paul old bean:

I seem to be interested in the Indian Camelback. In the last photo it appears to be indirect chain drive from the crank sprocket to a double sprocket with pedals for starting. Is there a clutch of any sort? Also it looks like a coaster brake at the back? With the engine a stressed frame member, how was the seat downtube attached to the head? Truly an ingenious machine, I’d love to see a snippet of one running.

Jim A., Tucson, AZ

Hi Jim. The pedals are used to start the bike, with the sprocket on the right side of the bike. So the big sprocket seen on the left side of the bike is free to spin relative to the pedals. I don’t think there is a clutch on these early models. I don’t see one… Coaster brake is on the left side of the rear hub, should be a freewheel on the right side.

ciao

Pete

I’m most intrigued by the Indian twin board track racer (with original magneto and plugs) the family acquired in the early 50s. Everyone seems to have an “original” BTR these days but this actually seems like the real thing. Very interested to know what it’ll bring at auction.

Last, rhetorically, will a genuine original-condition Camelback bring more than an over-restored one owned by Otis Chandler (that sold last year)? Will authenticity triumph over peer prestige?

-JZ

The Dupont story was fantastic, well –

d`Orleans and du Pont – who should find out these histories if not you…

Stefan

I’ve been to this museum in PA

In addition there are Penn Railroad cars and bi-planes

awesome place

DC