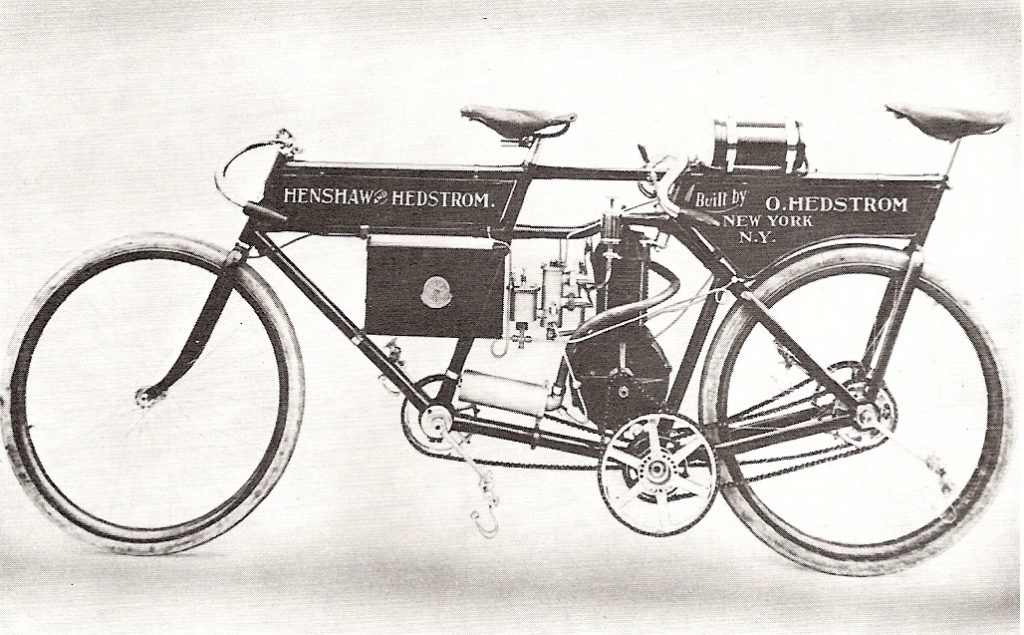

Born in 1880 in eastern Quebec, Jacob de Rosier was a French Canadian, but his family soon moved to Massachusetts. His two-wheeled competition career began at age 14 as an amateur cyclist at Fall River, Mass., but his talent soon saw him re-designated a professional cyclist, and he pursued pedal power until 1898. That November, he spied the two motor tandems imported from France by Henri Fournier for use as pacers in cycle competition. Jake was immediately drawn to the powered cycles, and proved very good at managing these unwieldy devices. De Rosier was consequently selected as a steersman in the first motor-paced cycle event ever run in the US, held at Waltham, Mass. at the end of 1898, in which he paced the famous Harry Elkes. The advent of motor pacing revolutionized cycle sport in the US, as it had already done in Europe.[Adapted for TheVintagent from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’]

Operating a motor tandem was not for the faint of heart; keeping an internal combustion engine alive and spinning was a hands-full occupation for a dedicated mechanicién, while a the steersman kept the whole contraption pointed in the right direction. According to a January 1900 commentary on the new technology, “The experience of running a motor at 40 miles an hour is thrilling, and requires nerve, which is often found wanting if a ‘chauffeur’ should have ever experienced a fall”. The ability to ride or race a bicycle was no guarantee of skill at handling a motorized tandem.

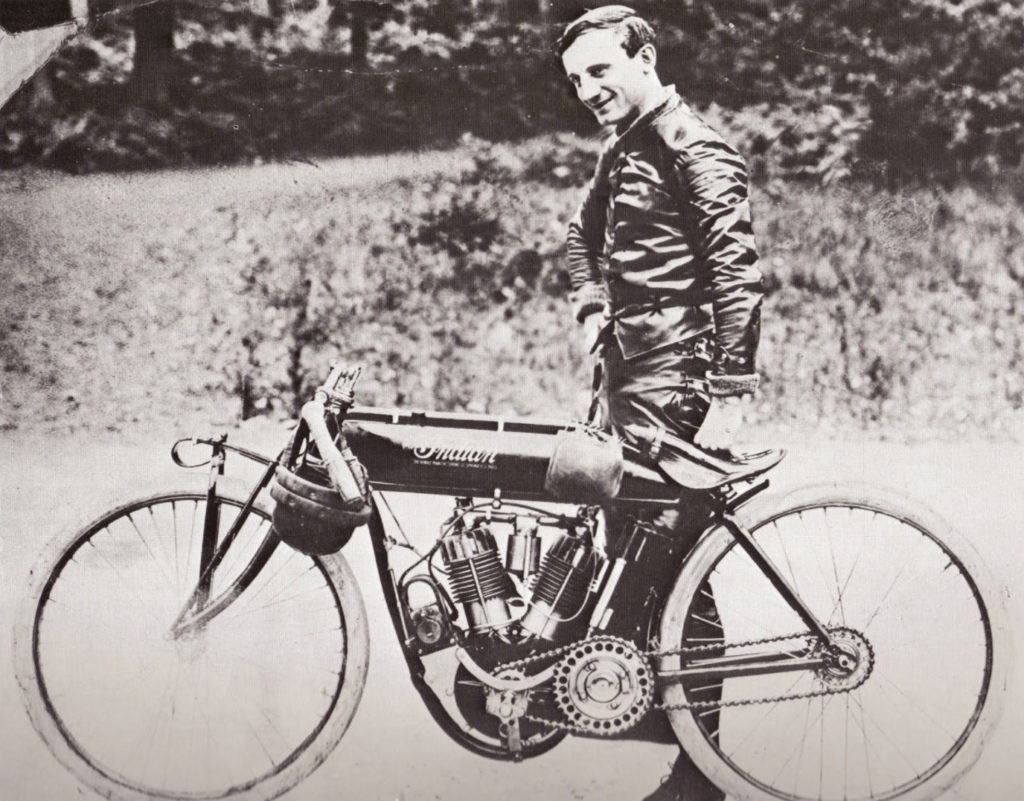

The Hendee Mfg. Co. hired de Rosier as a pacer-driver and a mechanic in 1901, but his employment lasted just a few months, and he continued his ‘pacer’ career for cyclists like Jimmy Michael until around 1905. The pacer crews at cycle races began to stage races with each other, in addition to supporting the bicycle competition. From 1905 de Rosier dropped the trailing cyclists and switched to motorcycle racing which was now gaining ground as a sport in its own right. As a result of various mishaps and spectacular get-offs it is said that, toward the end of the new century’s first decade, small and slightly-built De Rosier had not a patch of skin more than three inches square that had not yet been gouged, cut, bruised or torn. Of broken bones, multiple fractures and missing ribs there was now an extensive catalogue in his weighty medical file. His grit and determination to get to the top of this glamorous but dangerous new sport, and stay there, was evident in his conduct, his competitive spirit, and his refusal to be deterred by the prospect of further physical agonies or months-long spells of enforced idleness in a hospital bed. In the summer of 1908, Oscar Hedstrom presented de Rosier with a new experimental Indian to take away and test. It looked very different from Indian’s first motor bicycles, the ‘camel backs’. The new machine had a huge v-twin engine with scarcely any cylinder finning, slung low in a loop-frame rather than perched high in a bicycle frame. Jake spent his summer in New Jersey doing demonstration rides, setting national speed records on a cycle board track, and throwing down cash-purse match race challenges to other motor bicycle competitors. As a result of his successes on the prototype loop-frame racer, de Rosier was again hired by Indian, this time to be their official factory rider, becoming the world’s first professional salaried motorcycle racer.

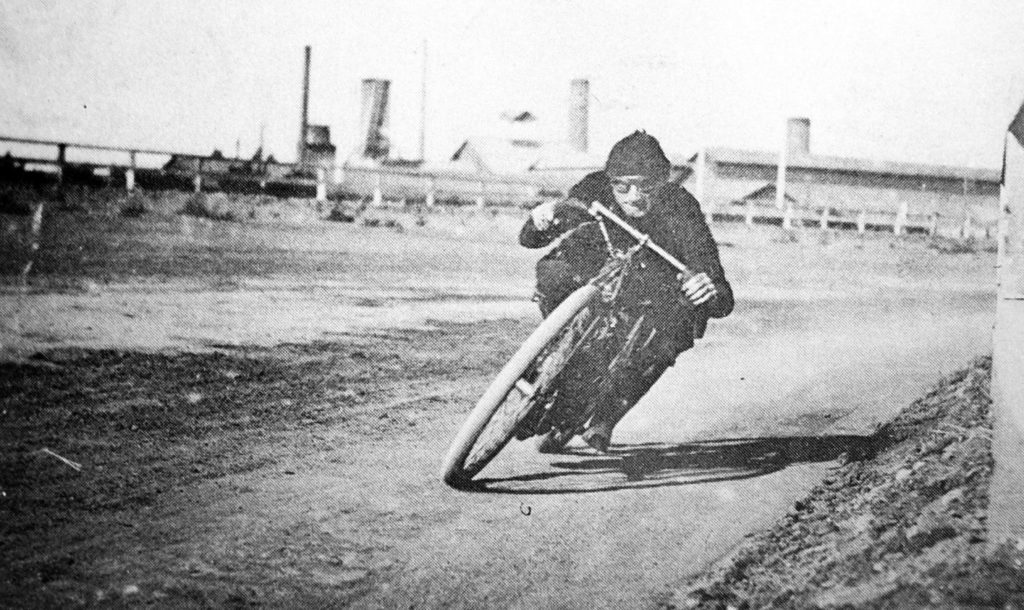

He quickly repaid Hendee’s investment, with interest. By 1910 he held the US records for all distances from one to one hundred miles in the name of Indian. He was firmly established as the major star of US motorcycle racing, among a coterie of riders whose gladiatorial feats had greatly popularized the new sport and of whom it was said “They furnish excitement as thrilling as it is served in any form and cause one’s blood to creep every minute they are in action”. Timber board tracks were now being established all over America by promoter Jack Prince. By early 1911 racing and record-breaking speeds in the USA soon climbed over 90 mph, undreamt-of and widely doubted in Britain where the mid-eighties was the best that anyone could yet manage. When Oscar Hedstrom decided that Indian should go all-out to be “third-time-lucky” and win the 1911 Isle of Man TT race, de Rosier was detailed to show the British what he could do. On arrival de Rosier was treated like a star and became the centre of a media circus; everywhere he stopped, crowds gathered to see and meet him, and his magnetic personality, and modesty about his riding ability, charmed the English and he became very popular.

In the TT itself de Rosier struggled, riding valiantly but clearly not comfortable on the rough and loose surfaces of the IoM’s gravel roads. He was leading the race at the end of the first lap, but had crashes and then accepted outside help which disqualified him. Yet he managed to ride the full distance. It was the British Indian riders who secured the 1-2-3 placings, after Charlie Collier of Matchless lost his own 2nd placing due to disqualification for re-fuelling at an unauthorized stop. The next day, de Rosier stunned the crowds by winning several sprints held down the narrow and curved Douglas Promenade, in windy and slippery conditions, at 75mph. De Rosier had brought with him “Number 21”, the 1,000cc Indian upon which he’d set all his current US records.

He was looking for match races and he found them, for it was arranged that he should have a Best-of-Three with English champion Charlie Collier (builder/rider of Matchless motorcycles) for a purse of £130. This was held at Brooklands Track near London, and the first race was won by de Rosier who slip-streamed Collier and then dashed past in the final instant. In the second race Collier led, and won because de Rosier’s front tyre came off at high speed. Yet Jake didn’t drop the bike, and he motored it back on the bare steel rim. The spectators were astonished by his skill. In the final race Collier again led, until his spark plug wire came loose. While struggling to hold it on with his bare hands, de Rosier came past to win. Before leaving England, de Rosier also broke the existing British one-mile and one-km speed records. But Charlie Collier had the final word after Jake had departed, for Collier next got his Matchless machine to take back all Jake’s records just set and he also became the first man in Britain to exceed 90mph.

Back in the USA, Jake soon fell out with Indian’s Board for reasons that are still not clear. For some reason, de Rosier was not presented with one of the new Indian eight-valve racers, which had been released while he was away in England. As a result, Jake joined the race team of Chicago firm Excelsior. But he soon had other problems. A new Excelsior rider named Joe Wolters burst onto the scene and started breaking all of Jake’s US records. Other too, like Erle Armstrong, found that the French Canadian was no longer unbeatable. Newspapers began referring to him in race reports as “the former champion” and “the old war-horse”. In February 1912 Jake and the Excelsior team went out west to compete in events at the newly-opened L.A. Stadium saucer board-track. Promoters played up race duels between de Rosier and Charles “Fearless” Balke as crowd-pleasing grudge matches. It was in one of these that a mistake by Balke saw both bikes go down and, locked together, they dragged their riders along for almost 500 feet. Balke was okay, but de Rosier’s left leg was broken in three places. He underwent surgery to pin everything back together, and then rested for a good many weeks, before further surgery and weeks of bed-rest, and by the time he was able to return home to Springfield Mass, all his savings had been spent on medical bills. As his leg had not healed properly, in February 1913 de Rosier entered hospital for yet another round of surgery. It didn’t go well, and he died on 25 February 1913. As de Rosier was quite famous in Springfield, home of the Indian Motocycle Co., his funeral cortege wound through the town, and as it passed, all work at the Indian factory ceased, and their flag was lowered to half mast. Ocscar Hedstrom tendered his resignation from Indian that very day, for reasons which have never been explained.

[Adapted from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’, by Timothy Pickering, Chris Smith, Harry V. Sucher, Liam Diamond, and Harry Havelin, available here]

Related Posts

August 9, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 4: Oliver Godfrey

Oliver Cyril Godfrey won the 1911 Isle…

August 5, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 3: Charles Bayly Franklin

Charles Bayly Franklin was Ireland's…

July 27, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 1: Billy Wells

Over 100 years ago, Indian swept the…

What a lousy way to die. Not even in the heat of action but a lingering slow death.

Epic stuff. The retelling keeps these heroes alive.

Greatness! They were Heroes.