[Adapted for TheVintagent from the excellent book ‘Franklin’s Indians’]

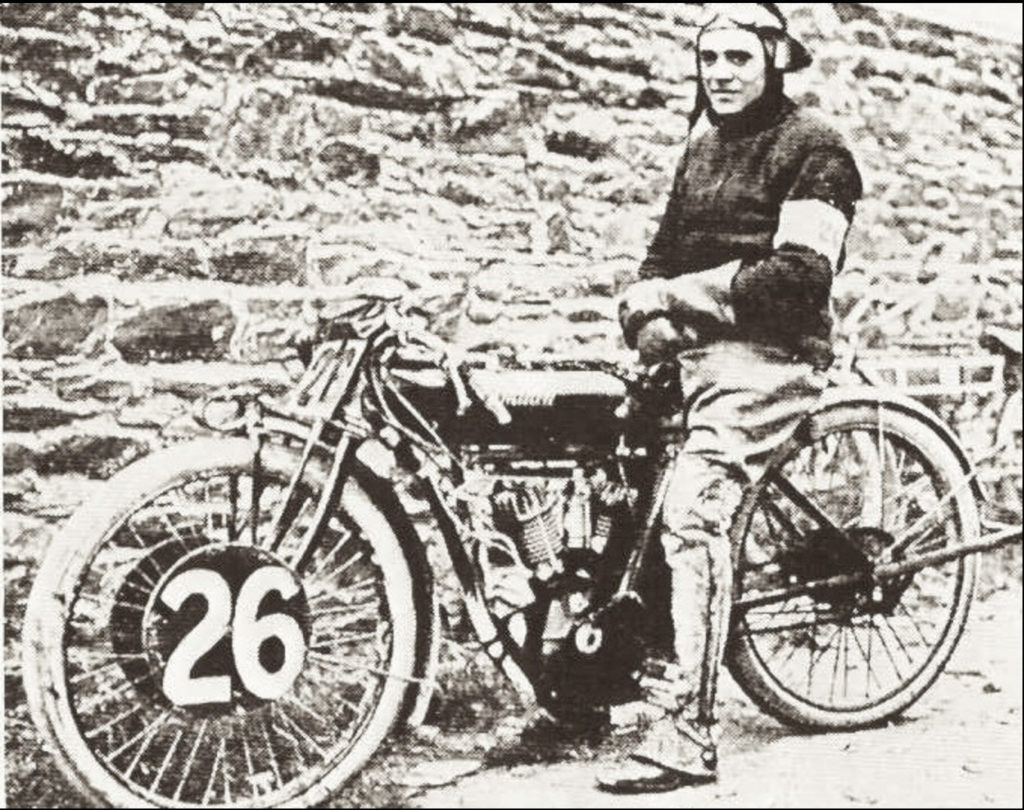

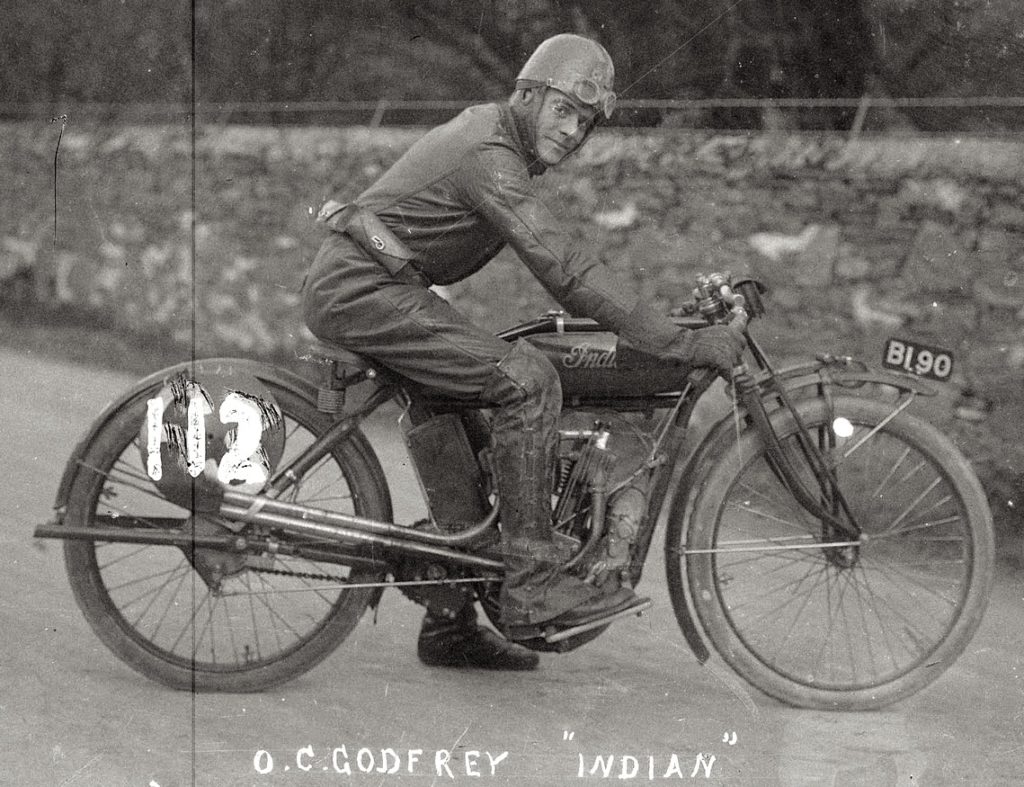

Oliver Cyril Godfrey was born in London in 1887 to an artist father, a painter and engraver, who decamped to Australia before 1901. Mrs Godfrey eventually remarried, and as late as his 1911 TT win, he was still living at his mother and step-father’s home in Finchley, employed as a ‘motor spindler’ (ie, machinist). By this time, young Oliver was a dedicated racing motorcyclist, and began racing at the Isle of Man by the age of 19, first on 726cc Rex twins in 1907 thru ’09, then the ubiquitous Triumph single-cylinder in 1910. He at last won the TT in 1911, on his fourth attempt, and raced on the Island until 1914, but didn’t get far in 1912, when mechanical trouble at the start line put paid to dreams of a second win. All his TT appearances from 1911 onwards were aboard an Indian.

Godfrey was one of five riders supported by the Indian factory to enter the 1911 TT, the other riders being a mixture of English, Irish, Scots and American in the form of Arthur Moorhouse, Charles Franklin, Jimmy Alexander and Jake De Rosier respectively; all these riders are profiled in The Vintagent. The Indian team was managed by UK Indian concessionaire Billy Wells of the Hendee Mfg Co.’s London branch, and “technical advisor” was the great Medicine Man of Indian himself, chief engineer Oscar Hedstrom.

Given the unpaved, country roads which comprised the Isle of Man TT course in those days, falls over the dirt, mud, and stones were common; both de Rosier and Alexander had significant crashes in 1911, yet Godfrey rode consistently and well to finish the race without a fall, just ahead of Charlie Collier (Matchless) who was second to cross the finish line. CB Franklin similarly had a straightforward race, and Moorhouse, although he did fall off once, kept his place on the leader board. Collier had misjudged his gasoline consumption and was forced to take on fuel at an unauthorised filling point, and was disqualified, which elevated Franklin and Moorhouse to 2nd and 3rd places.

Godfrey’s winning feat established a number of “firsts”, including the first ever ‘1-2-3’ clean sweep by a factory team, first TT win by a foreign manufacturer (Indian), first Senior TT win, first win on the new ‘Mountain’ course over Snaefell mountain (the same course used today), and first Mountain course Race record (though Frank Applebee’s Scott set the first Mountain course Lap record). In a rather upbeat TT race report reprinted in the 1912 Indian UK sales catalogue, Godfrey was described as “small in size, but a bunch of muscles and nerves and a magnificent rider”.

Godfrey failed to start in the 1912 TT, “Did Not Finish” in 1913, but was able to claim 2nd place in the 1914 Senior TT. His Isle of Man record and results at the Brooklands Track in Surrey place him at the forefront of motorcycle racers pre-World War One. Godfrey was a business partner with 1912 Senior TT winner, Scott-riding Frank Applebee, in Godfreys Ltd, motorcycle retailers located at 208 Great Portland Street, London W1. This firm continued trading until the 1960s. A 1920 magazine advertisement laid claim to experience in all aspects of the motorcycle trade “including winning the 1911 and 1912 TTs”. Certainly a rare attribute!

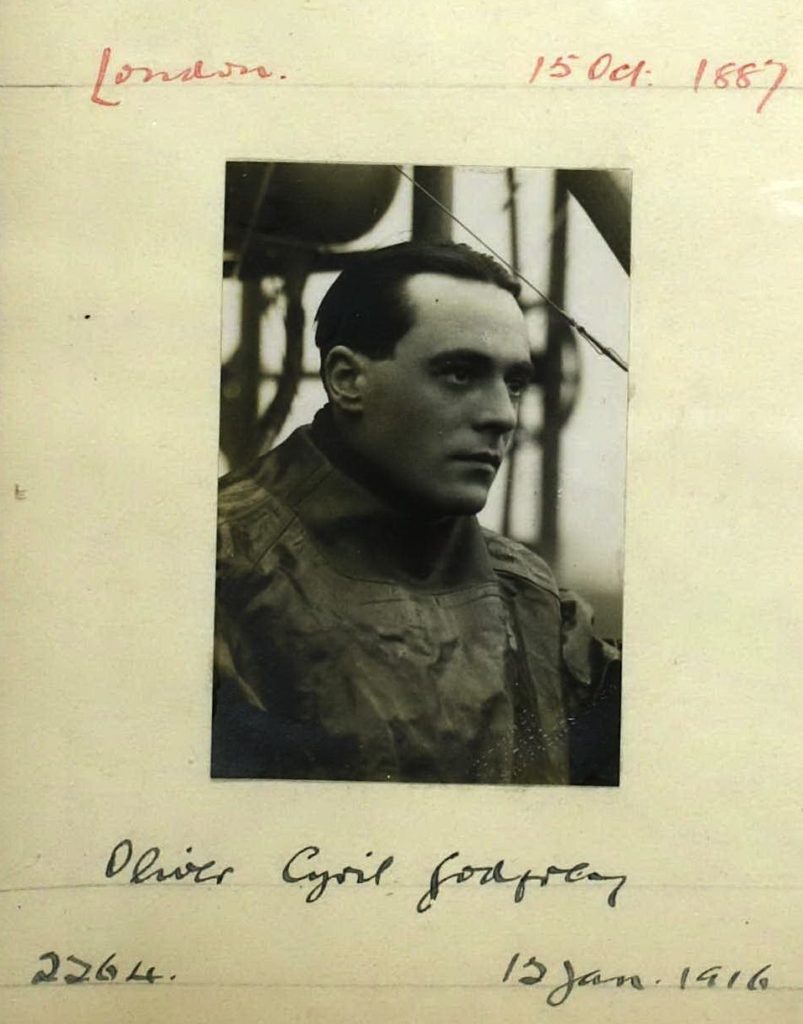

When war against Germany was declared in 1914, Godfrey enlisted as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps. He earned his Royal Aero Club Aviator’s certificate in a Beatty-Wright bi-plane at Hendon (now a massive RAF museum) in January 1916. The RFC used the Royal Aero Club for pilot certification through WWI, training about 6300 pilots during the War. In the photo above, from Godfrey’s flying certificate, the wires behind him are likely wing-wires on his Beatty training bi-plane.

Oliver Godfrey was posted to 27 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps which first arrived in France in March 1916 and by June was based at Fienvillers, 10 miles west of Albert in the Somme Valley, and 15 miles behind the front lines. Their “base” used a cow pasture for a runway, where the fliers and ground-crew all slept in tents. The squadron was equipped exclusively with single-seater fighter scouts, the Martinsyde G100, nicknamed the ‘Elephant’ as it was big and responded slowly to pilot input. Unsuitable as a fighter, the ‘Elephant’ had a long flight range, so was redeployed as a bomber and reconnaissance scout, and flew missions up and down the western front, to Bapaume, Cambrai and Douai.

The bombing success of 27 Squadron became their main role from 9 July 1916 onwards, and enemy airfields at Bertincourt, Velu and Hervilly were added to the list of targets. Oliver Godfrey joined the Squadron at this point, a relatively easy period for British fliers, when the chances of survival were still reasonable. The start of the Third Battle of the Somme on 15 September saw the squadron attack General Karl von Bulow’s headquarters at Bourlon Chateau, followed by more bombing of trains around Cambrai, at Epehy, and Ribecourt. By August 1916 the German Imperial Army Air Service was reorganized, and new “hunter” squadrons were created, becoming the pioneers of specialist fighter aircraft formations and tactics (the ‘Dicta Boelke’), soon to be universal. The first ‘hunters’ were Jagdstaffel 2, formed at Lagnicourt, under the command of Oswald Boelcke, Germany’s top-scoring pilot at the time, and a young Manfred von Richthofen (the ‘Red Baron’) was among pilots hand-picked by Boelcke for the new unit, and by 16 September Jagdstaffel 2 had received enough of its allotted aircraft to commence operations in earnest.

For RFC units like 27 Squadron, their ‘honeymoon’ in France was definitely now over. It was during a bombing mission by six Elephants to Cambrai on 23 September that Oliver Godfrey lost his life, most likely shot down by Hans Reimann of Jadgstaffel 2, who was himself killed in the same engagement. The events of that day are described in a history of 27th Squadron written by Chaz Bowyer: “On September 22nd bombing raids were carried out on Quievrechain railway station. One pilot, seeing that his bombs had failed to explode, proceeded to strafe the engine driver of a train attempting to leave the station quickly. Later in the day, fifty six 20lb bombs were scattered in Havrincourt Wood, suspected of harbouring German infantry. The following day 27 Squadron sent six Elephants on an Offensive Patrol over Cambrai, setting out at 8.30 am. All six were attacked over Cambrai by five Scouts of Jagdstaffel 2 led by Boelcke in person – with disastrous results for the Martinsydes. Sgt. H. Bellerby in Martinsyde 7841 was shot down almost immediately by Manfred von Richthofen (his 2nd official victory) while within seconds two more Elephants piloted by 2/Lts. E.J. Roberts and O.C. Godfrey were destroyed by Leutnants Erwin Boehme and Hans Reimann. Recovering from the shock of the first German onslaught, the remaining three Martinsydes continued the fight despite being outnumbered and outclassed by superior German aircraft. Lt. L.F. Forbes having exhausted all of his ammunition made one last defiant gesture by deliberately charging at the Albatros piloted by Hans Reimann, ramming the German scout in a near head-on collision. Reimann spun to earth and his death in a crushed cockpit, but Forbes, in spite of one collapsed wing with aileron controls shattered, managed to nurse his crippled Martinsyde towards base.”

Godfrey had only been in France 3 months, and was one of 252 crew and 800 planes lost during this 4+ month campaign, in which the RFC lost a staggering 75% of its men in the battle…yet on the ground it was far worse, with 750,000 dead in an evil Autumn. Many of the pilots coming to France at that time were relatively inexperienced, deployed to replace downed airmen as fast as they could push them out of the training schools. German pilots, with vastly superior aircraft and plenty of tactical combat experience as the months went by, racked up hundreds of ‘kills’, before the tide of the war turned, and they in turn became the hunted.

When Godfrey was shot down, Cambrai was situated miles behind enemy lines, and its unclear what became of his body or whether, indeed, there was anything left in the burned-out wreck to bury. His memorial is Ref. IV. F. 12. at Point-du-jour Military Cemetery, Athies, near Arras. On settling his estate some 18 months later, the small fortune of £1475 went not to his mother, but to Frank Applebee, Scott-mounted winner of the 1912 TT and Oliver’s business partner in Godfrey’s Ltd, the motorcycle dealership in London which carried its founder’s name nearly 50 years after lying down in the green fields of France.

[Adapted from the book ‘Franklin’s Indians’, by Timothy Pickering, Chris Smith, Harry V. Sucher, Liam Diamond, and Harry Havelin, available here]

Related Posts

August 5, 2017

100 Years After the ‘Indian Summer’, Part 3: Charles Bayly Franklin

Charles Bayly Franklin was Ireland's…

Very nice work with the Godfrey story, you’ve really added value to it.

By way of eerie coincidence, those are Australians that are guarding Richthofen’s plane. Corporal Roy Brown of 3 Squadron RAFC not only helped recover the body and place it under guard, but also led the firing party for the salute at Richthofen’s funeral. Brown’s grandson Jim Parker is these days one of Australia’s leading Indian restorers (parkerindian.com.au). A tenuous link perhaps, but another weird example of how a marque of inanimate machinery like Indian can be the thread that binds people together!

We’re really getting down to fine details now, however the place where Godfrey and his two colleagues were shot down is Beugny, which is 5km northeast of Bapaume and 19km southwest of Cambrai. Not so far inside German lines as Cambrai itself, but well inside (Bapaume was in German hands). Evidence – the “kills” of Manfred von Richthofen, of which Bellarby’s Martinsyde was his second (http://www.jastaboelcke.de/aces/m_v_richthofen/manfred_victories.htm).

Cheers

TIM

Hi Paul

More in the “anorak” category, this time on what most likely became of Oliver Godfrey’s body. The following excerpt is from Red Baron: the life and death of an ace by Peter Kilduff. No change needed to our article, but rather it’s good to confirm that our wording is consistent with this as the most-likely ultimate fate of Godfrey.

A ground mist on the morning of 23 September did not prevent Boelcke

and five comrades, including Richthofen, from flying over the main road

from Bapaume to Cambrai. Over Bapaume they spotted six ungainly

Martinsyde G.100 ‘Elephant’ single-seat biplanes, which proved to be aptly

named as they plodded along and came under the guns of the sleek, fast and

manoeuvrable Albatros fighters of jasta 2. Knowing just what to do, Manfred

von Richthofen pounced on his prey and quickly sent it down.

Richthofen’s second victim was Sergeant Herbert Bellerby, age 28, of

No. 27 Squadron, RFC. Apparently, infantrymen buried the body of the 28-

year-old Essex native where he fell, as British records indicate he has no

known grave.

Richthofen’s success, however, was marred by ]asta 2’s loss of Leutnant Hans

Reimann. After shooting down a Martinsyde, subsequently credited as his

fourth victory, Reimann was rammed by another Martinsyde; the British

pilot managed to escape in the badly damaged aeroplane and make his way

to a British airfield. Reimann’s Albatros fell to the ground and the pilot, age

25, was killed in the crash.

That evening, while Jasta 2 was being moved a short distance north to the

airfield at Lagnicourt, Richthofen ordered a second silver cup from the

Berlin jeweller and had it inscribed: 2. Martinsyde 1. 23.9.16.

TIM

Fascinating and horrifying in equal measure, the nature of air combat was so personal in those days. Staggering casualty rates, and for what? It still amazes me that ‘the war to end all wars’ didn’t, and Europe was back at it in 20 years… ah well, ‘war is the health of the state’ and all that.

I never found hard evidence of the import duty increase in the mid-1920s on bikes. France seems to have levied 40-100%, depending, but Britain just seems to have sent their economy in a spiral by going on and off the gold standard, fiddling with interest rates in exactly the wrong way, etc. the consensus being every other economy in Europe did ok in the 20s by ‘doing nothing’, whereas Britain had smart-ass economists who really mucked things up by tinkering with the system.

Fascinating stuff.

The pilots themselves preferred it to be personal. One-on-one like medieval knights jousting, where both had an equal chance and if you lost, then it was because the better man won. That kind of war they regarded as a gentleman’s game and all good sport. What they abhorred was the mindless mass killing below them, by impersonal artillery fire or horrible chemical warfare. Leutnant Ernst Boehme wrote a letter to his mum along these very lines …

TIM

Not all that different from motorcycle racing, except the killing bit.

I’ll google Boehme’s letter; all grist for the mill. I’m always happy to include a bit of ‘outside’ history into The Vintagent, especially when its so directly relevant. The aviation/motorcycle connection has always been strong, between designers, manufacturers and riders, from BMW to the Hell’s Angels.

Given the generally unreliable nature of motorcycles in 1916, it amazes me that these planes could engage in long-range flights and dogfights at all, but I suppose that’s more a matter of placing resources in RnD than any true technical barrier.

Also interesting that air combat remained rather personal until after the Korean war, whereas bombers became detached from the results of their work by the 1920s.

Are you a fan of Antoine de St Expury? ‘Flight to Arras’ is one of my favorites, as is ‘Night Flight’, with stunning imagery of mail runs from Africa to South America, with water spouts climbing like huge colonnades under the moonlight, and the Andes as dramatic and frightening as the moon.

This being the 100 anniversary of the Indian 1,2,3 win at IOM TT there will be 2 1911 Indian IOM TT Racers at IOM for a celebration. 1 built by Pete Gagan of BC, Canada and Chuck Garrett of florssant, Missouri, USA. Chuck Garrett

Oliver was my mum’s uncle. Mum came from the New Zealand part of Oliver’s Dads life when Louis came to Aust/then NZ with their London housemaid Fannie(my great grandmother!)and Oliver’s older brother, Louis. I note Oliver’s cousin was the Godfrey of HRG Cars(Henry Ron Godfrey)who also founded GN cars with Archie Frazer-Nash and later in 1929 they both built the Frazer-Nash aircraft gun turret. I also joined the Air Force as a pilot but not for long.

TIM said: “By way of eerie coincidence, those are Australians that are guarding Richthofen’s plane. Corporal Roy Brown of 3 Squadron RAFC not only helped recover the body and place it under guard, but also led the firing party for the salute at Richthofen’s funeral.”

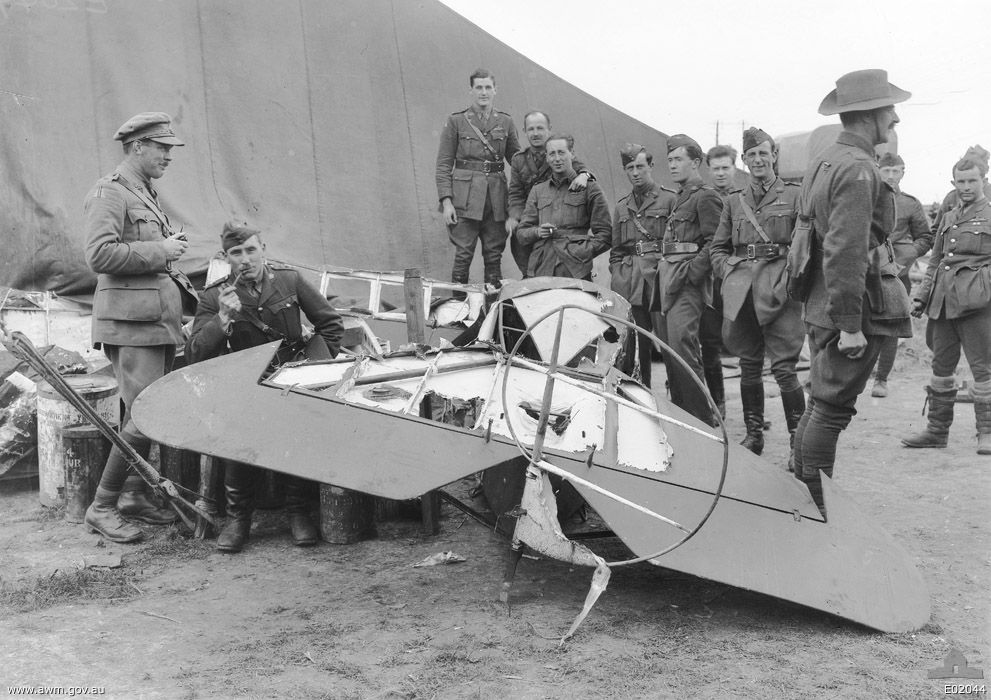

The sentry is certainly, and his officer behind him probably, an Australian. If the others are Australians, then the Air Force Glengarry must have come in earlier than I thought. This is the first time that I have seen Brown credited to the A.F.C. (no “R.”). I thought he was a Canadian. In any event he was 1) like all British pilots, an officer (in his case Capt) and 2) a long way from Richthofen’s aircraft when the latter brought it down (it was not ‘shot down’, but landed in No Man’s Land in front of the Australian trenches). The Australian infantry rushed out to it and got there just in time to hear the Baron’s last word: ‘… kaputt’. It was they who removed his body, uninjured except by the fatal .303 bullet (not one of Sgt Popkin’s!), and it was Australian souvenir-hunters who quickly reduced the machine to the state seen in the picture, which in my opinion was taken outside the wall of Bertangles castle, the H.Q. of the A.F.C. near Amiens, where shortly afterwards Monash was knighted in the field by King George V. It was certainly not taken on the battlefield, as witness not only the wall but also the headgear (no tin hats) and spick-and-span appearance of the assembled soldiery who are smiling for the camera. Large pieces of the aircraft, some of them donated or bequeathed by the souvenir-hunters of 1918, can still be seen in the Australian National War Museum in Canberra.

Hi

Just to let you know that the picture of Martinsyde Aircraft B’872 is of my Grandfather Captain Kenneth Noble Pearson MC. I have the original photo at home.

regards

Ian C Pearson

Clacton on Sea

Further to Pamino’s comment aboutthe demise of the Red baron, here’s a quote from an article I researched and wrote for The Indian News, magazine of the Indian Motorcycle Club of Australia:

“As is well known, Manfred von Richthofen also met with an untimely end. And as with the death in action of Oliver Godfrey, there is also a connection with Indian motorcycles. The Red Baron was shot down on 21 April 1918 while in low-level pursuit of a Sopwith Camel deep inside Allied territory in the Somme valley, near Morlancourt ridge. Though long controversial, it is now generally accepted that he was brought down by ground fire. A post-mortem examination revealed that Richthofen was killed by a single .303 bullet that entered under the right armpit and emerged near his heart. His Fokker came down largely intact in a field on a hill close to the Corbie-Bray road just north of Vaux-sur-Somme, but the Red Baron was either already dead or died very soon after. Australian troops were first on the scene. It was fitters and riggers of the nearest air unit, 3 Squadron Australian Flying Corps based at Poulainville, who recovered Richthofen’s body from his aircraft and placed it under guard. 3 Squadron’s officers and men were given responsibility for his burial.

The funeral took place at the village of Bertangles (the site of Australian Corps Headquarters) with all of the honours befitting Richthofen’s status and rank. The man in charge of the guard of honour that formed the firing party for the final salute at the graveside, and one of those who’d helped to recover the Baron’s body, was Corporal Mechanic Roy Brown. By weird coincidence, the Canadian Sopwith Camel pilot that Allied propaganda erroneously credited with shooting down Richthofen was named Arthur “Roy” Brown. This Australian Roy Brown was, however, a fitter and rigger in 3 Squadron AFC. The connection with Indian motorcycles? Okay, it’s a little tenuous, but Roy Brown’s grandson, Jim Parker of Parker Indian Restorations Ltd in Melbourne, is nowadays Australia’s leading Indian restorer and marque specialist.”

TIM

While reading in my Indian book, I started wondering why Oliver Godfrey just suddenly disappears ? I feel so blessed to find his story. He was a great man , and God bless him and his family ! He is an inspiration to me forever. Thank you Rick Montgomery, Indian rider and American..

My Daughter Francesca and I visited Oliver’s grave last year after going to the Gallipoli 100 year event in Turkey. The cemetery is a bit tricky to find but immaculately maintained. It literally looked like it was finished the day before. The rules said no flowers to be left so we accordingly left some flowers.

On the co-incidence front it happens that one of the authors of “Franklin’s Indians” is a friend from Wellington (Tim Pickering) who we have known for 27 years. I had no idea he was an Indian specialist!

Godfrey Husheer (Oliver’s nephew) hill climbed a heavily modified James197cc machine in Napier, New Zealand and also rode a Calthorpe. I run a 1942 BSA WM20 almost daily (ex Malta RAF service).

My grandfather was Oliver’s boyhood friend and business partner – Frank Applebee. Our family remembers Oliver too with my mother named Olive and one of Frank’s grandsons having Godfrey as a second name.

Rodney Hammett