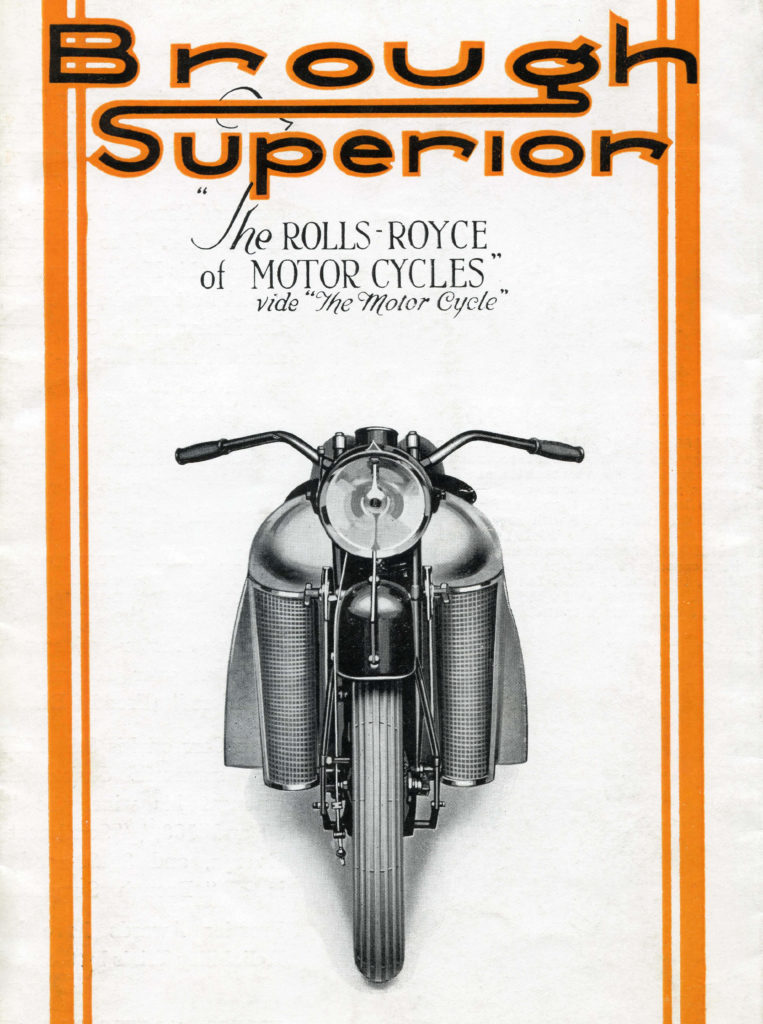

The last of the species died so long ago we’ve forgotten it once existed; the luxury motorcycle. An oxymoron today, those two words once sat as comfortably together as cigarette and holder, or top and hat. In this century one finds so-called luxury items advertised everywhere, which are likely mass-produced in charmless foreign factories. While ‘finished’ by artisans in their nominal home country, such items retain a mere thread of bespoke in our outsourced world; they are de-luxe, the light of tradition and exquisite hand craftsmanship having nearly been extinguished.Why the most luxurious motorcycle ever built has 3 wheels.

[Originally published in The Automobile magazine, the world’s best vintage car content]

Well done-a pleasure to read.

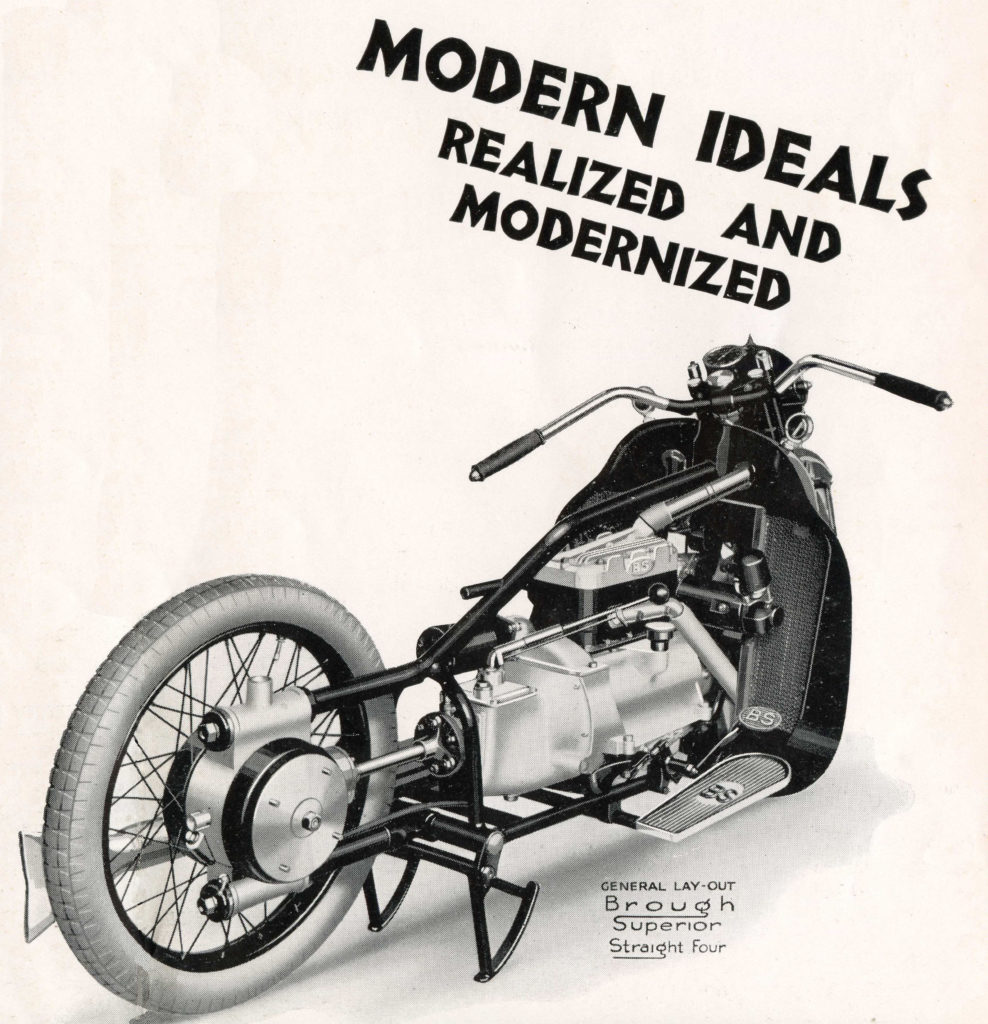

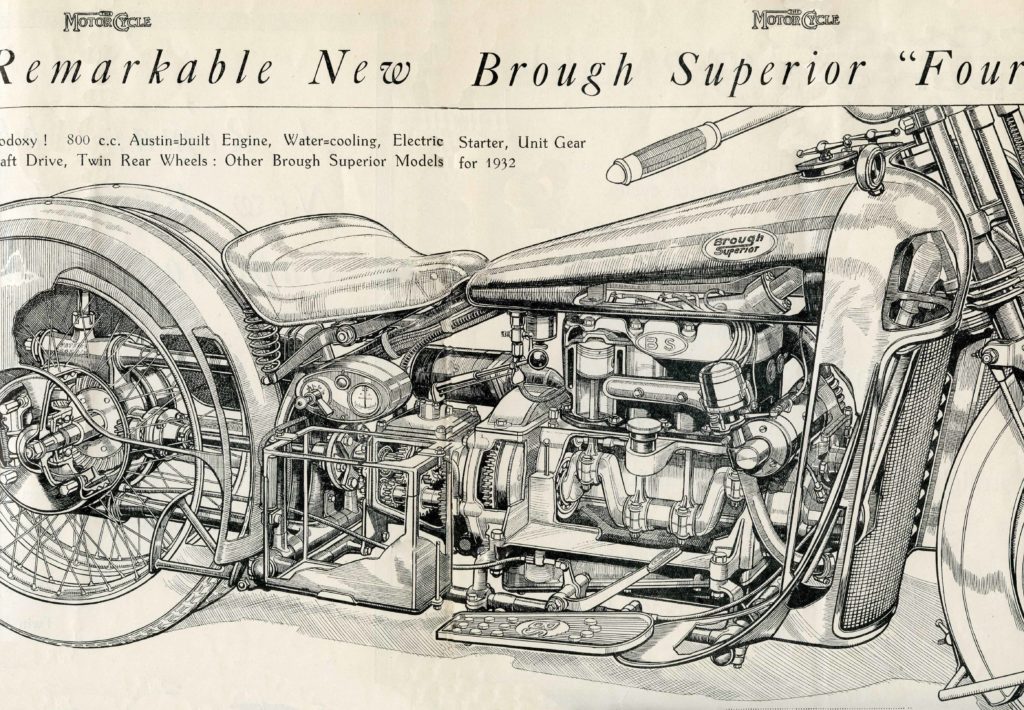

Ted Lester was one of GBs employees tasked with building the first BS4.They had been trying a bevel box to chain rear drive.It was much too long. GB had been to the pub,on whisky, came back having had a skinful……..& said twin back wheels and a bevel drive, which is how the BS4 got its back end.

The pub as an institution has inspired much creative British engineering, I’ve no doubt! Thanks for that Dave, I hadn’t heard it before.

I remember the day clearly back in the late 1990’s when after being given access to a very private ( and extensive ) motorcycle collection catching the gleam of a polished chrome gas tank hidden away towards the back realizing as I moved closer that it was the Brough Superior I thought it might be being completely blown away as I came nearer despite the multitudes of other bikes ( including my personal favorites .. Vincents ) in the collection. Truly the Brough Superior is the Rolls Royce of motorcycles past or present never to be equaled

( he say listening to Phil Lesh and friends w/BillFrisell .. ahh the irony .. 😎 )

I love your analogies Paul – “Half an hour on the BS4 was like sex with Catherine Deneuve in a Cannes dressing room; over too quickly, but savored ever after.” Hard to say if I’ve ever read a more evocative (or provocative!) sentence… 🙂

Notice zu mention the ‘v4’? but make no mention of the flat4 Dream!

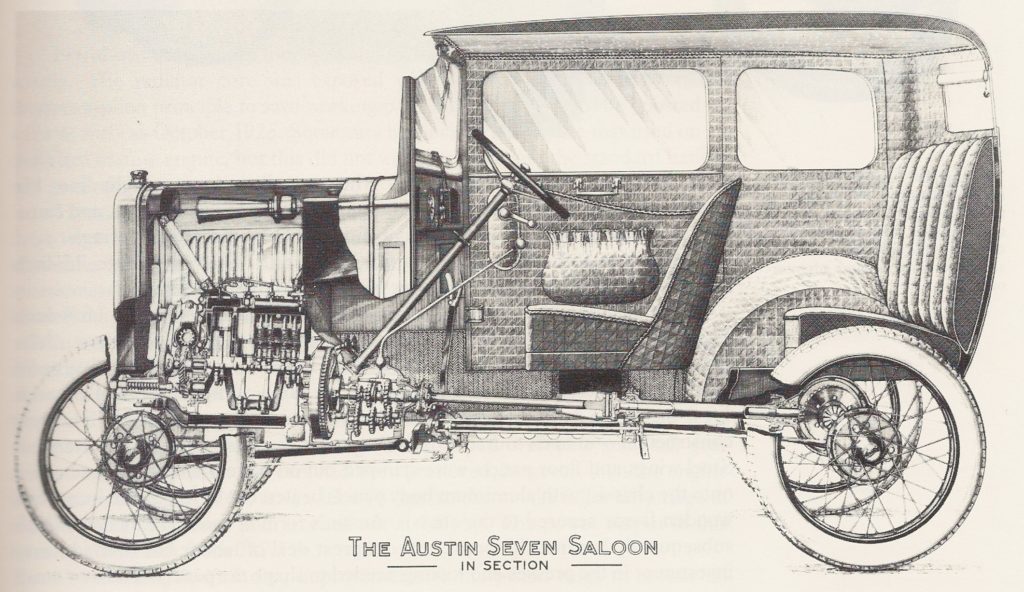

The Dream was built several years after the BS4: I mention George’s earlier attempts to build a four as a buildup to the only Brough Superior four-cylinder that actually worked, that used an Austin engine. By all accounts, the Dream did not work either…it’s not an easy thing designing an engine from scratch, and while George’s father William was adept at the practice, young George did not find success designing his own engines.