A Short History of World Motorcycle Speed Records, 1896-1930

When Sylvester H. Roper attached a small steam engine to an iron-frame ‘boneshaker’ bicycle near Boston in 1867, one question burned in his mind; How fast will it go? I have no doubt Guillame Perreaux asked himself the same question in Paris that same year, when he also attached a steamer to one of Pierre Michaux’s pedal-velocipedes. But it was Roper who was motorcycling’s first speed demon, and its first martyr. Every Café Racer on planet earth should affix to their bike a lucky charm with Roper’s visage. Forget St.Christopher – he never rode a bike; Roper is the true patron saint of motorcycles, and he died for the same sin which stains 21st Century bikers – the lust for speed.

On June 1st, 1896, at the tender age of 73, Roper was asked to demonstrate his ‘self propeller’, as he called it, on the Charles River Speedway, a banked wooden bicycle racing track in Cambridge, Mass. Roper’s steam cycle had a reputation around Boston as the fastest thing on wheels, being able to “climb any hill and outrun any horse”, as he stated. He was invited to pace a few bicyclists at the Speedway, which became a race, and Roper kicked their asses with the 65kph speed of the steamer. Track officials urged him to unleash the hissing beast, and the septugenarian inventor was excited to oblige. After a few scorching laps, Roper was seen to wobble and slow towards his ‘pit crew’ – his son Charles – into whose arms he collapsed, dead. Roper did not crash, but likely had a heart attack from the excitement. Roper became the first motorcycle fatality…not from a wreck, but from the thrill. He deserves a sprocket-edged halo.

== Burning Daytona Sands ==

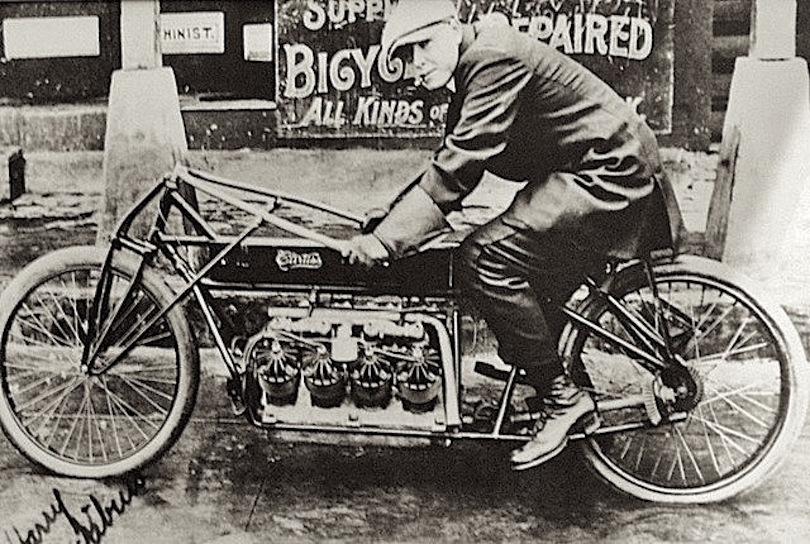

Glenn Curtiss inherited Roper’s lust for speed. As one of the earliest motorcycle manufacturers in the US, he’d caught the racing bug first on bicycles, then attached an E.R. Thomas motor to his bicycle in 1899, which he called the ‘Happy Hooligan’ (yes, our great-grandpa was cool). Curtiss thought the Thomas engine, which copied Comte DeDion’s design, was crap, so he built his own motor. Curtiss was a mathematical and engineering genius since his childhood, and his engines were reliable and performed better than anything else when introduced in 1905. Curtiss engines were so good he caught the eye of the fledgeling aviation industry, and began supplying motors for dirigibles. But Curtiss was more than an engineer; the question ‘how fast?’ burned bright in his soul, so in 1906 he constructed a spindly motorcycle frame around his V-8 dirigible motor, and travelled to Florida to test his monster on the only speed venue in the US; Daytona/Ormond beach.

Timed runs on the sand were conducted with cars and motorcycles, and Curtiss waited until the end of the day’s ‘normal’ speed runs, with ordinary production bikes, before wheeling out his 40hp Behemoth. He promptly scorched through a 1-mile trap at 136.3mph – the fastest speed of any powered human to date. His ‘return’ run was ruined by the disintegration of the direct shaft drive to the rear wheel (no surprise, with a sand bath for the exposed universal joint) and the rear wheel locked at 130mph, while the drive shaft flailed away at the rider… but Curtiss’ considerable racing experience won out, and he hauled the beast to a stop without crashing. A true American hero.

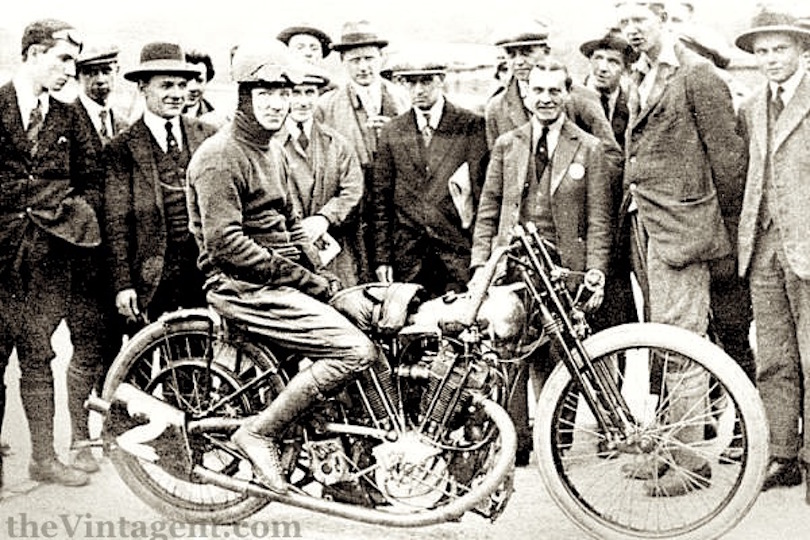

With time, the FIM was created to supervise Speed Records, and the first ‘official’ FIM ratified speed was taken again at Daytona beach, when Gene Walker pushed his Indian Chief to 104.12mph in 1920. That was the last time an American flag flew over the World Motorcycle Speed Record for 70 years. For their own reasons, American motorcycle manufacturers, who built the technical equal of any bike in the world through the 1920s, virtually disappeared from global motorcycle competition after 1923, when Freddie Dixon took 3rd at the Isle of Man TT on an Indian 500cc sidevalve single. America turned inward, to its own style of dirt-track racing, and the World Speed Records of the 1920s belonged exclusively to the British.

In 1923 Bert LeVack took a frame built by Claude Temple, stuffed it with a mighty 996cc DOHC Anzani engine, and bumped along at Brooklands, half airborne on the notoriously bumpy track. LeVack averaged 108.41mph, and the FIM didn’t have to cross the Atlantic again for motorcycles until the 1950s, when Bonneville became the location of choice for speed-mad riders.

== ALL ENGLAND, ALL THE TIME ==

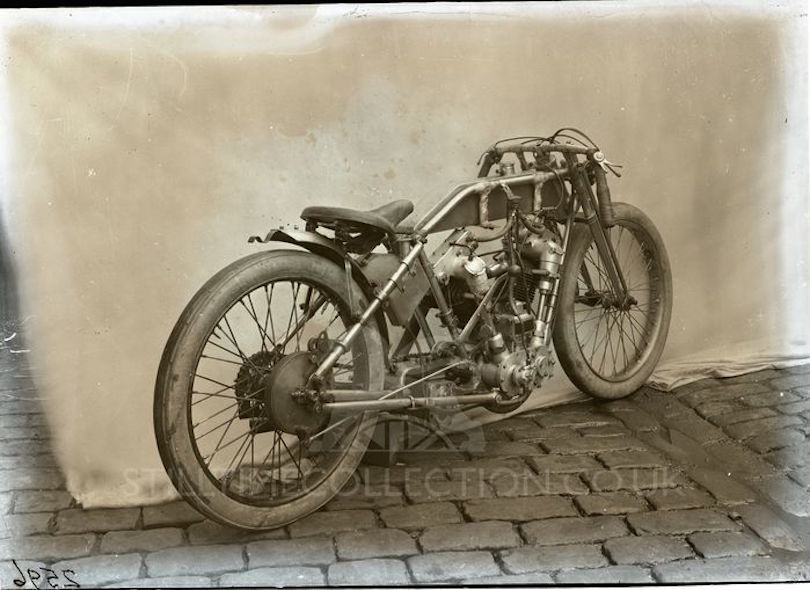

The rest of the 1920s was a fistfight between three tiny English workshops, sometimes called manufacturers, who all used JAP overhead-valve V-twin engines, and progressively made them faster. The hunt began for a new place to go really fast, as Brooklands was fine for racing, but horrible for speed records. A decent straightway was found near Paris, in the village of Arpajon, the future site of the Montlhéry speed bowl. The Arpajon road is still there and still very straight; if you got lost on your way to the Café Racer festival at Montlhéry, you probably took the very same road…but sadly, the roaring racers have long since been replaced by honking commuters.

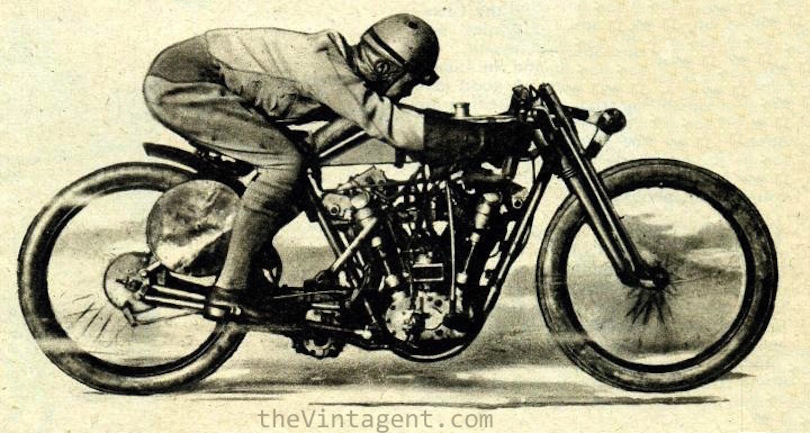

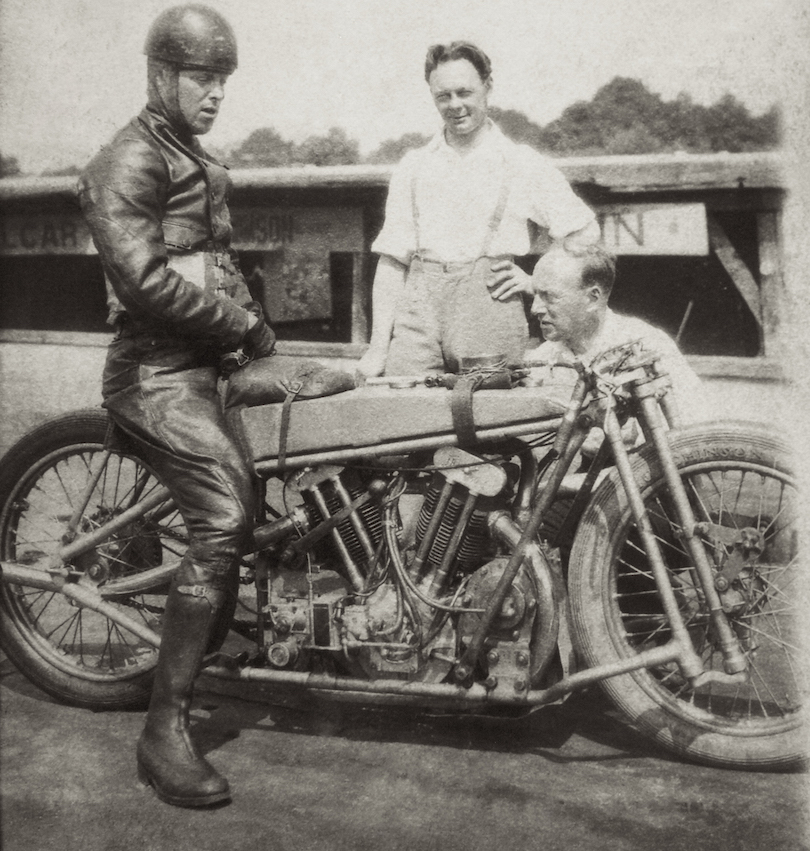

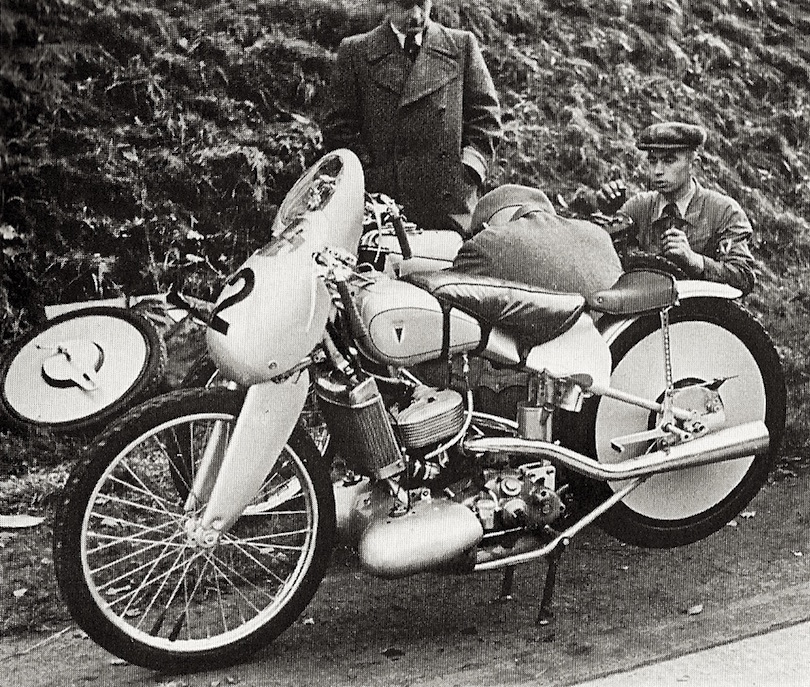

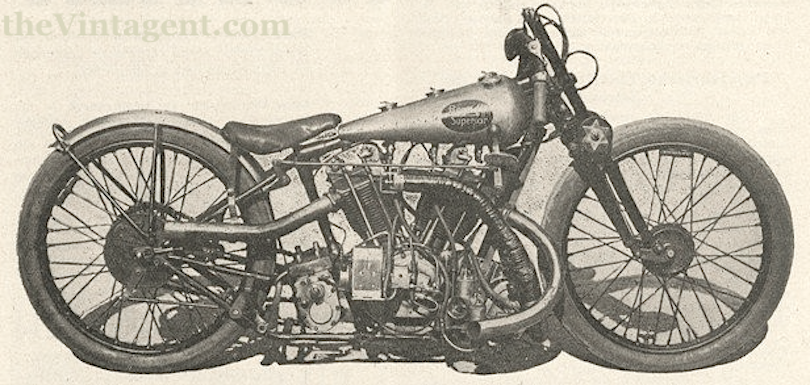

The immortal Bert LeVack became JAP’s racing engineer in the early 20s, and was hired by Brough Superior in 1923 for a new attempt on the World Speed Record at Arpajon, which succeeded at 118.98mph (or since it was in France, 191.59kph). Claude Temple wasn’t happy to have lost the record to George Brough, an egotist with no real racing experience, so Temple teamed up with the Osborne Engineering Company (OEC), who had unusual ideas about chassis design and steering systems (their nickname was ‘Odd Engineering Contraptions’). The OEC speed-record racer used a complicated ‘duplex’ front end, which was heavy and didn’t like turning corners – perfect for a Speed Record. Temple used a special 996cc JAP engine to re-take the record at Arpajon in 1926, averaging 195.33kph.

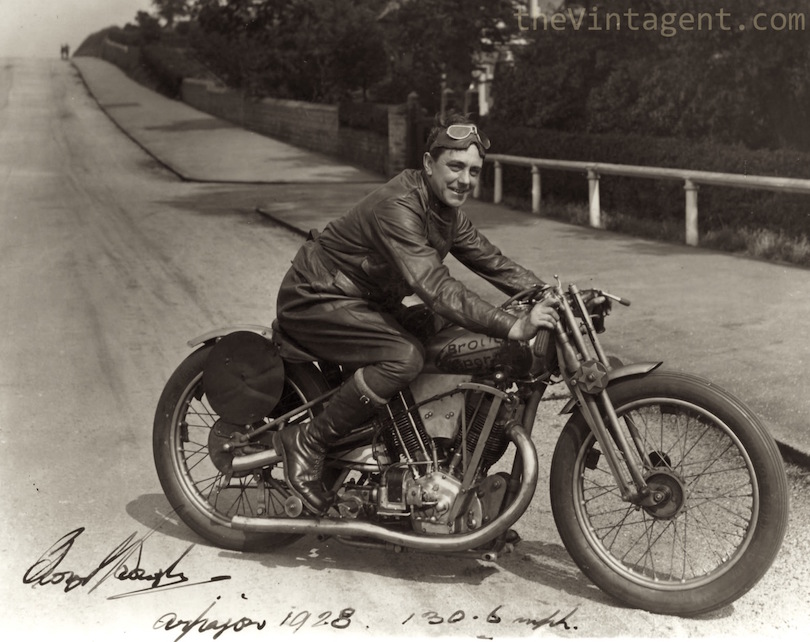

Freddie Barnes, the owner of Zenith Motorcycles, sold the only proper road-racing motorcycles out of all the English factories competing for Speed Record honors. While Brough Superior was flashy and self-promoting, and OEC was preoccupied with bizarre ideas, Zeniths were busy taking more ‘Gold Stars’ for 100mph laps at Brooklands than any other marque, and the tall, lanky Freddie Barnes was their guru. In 1928, he hired Oliver Baldwin, a Brooklands regular, to ride his 996cc KTOR JAP-engined Zenith to finally break the 200kph barrier, at 200.56kph.

George Brough could not bear it – who the hell was Freddie Barnes anyway? – and hired LeVack to breathe a little harder on the 996cc KTOR JAP (conflict of interest? Good business for JAP!) and heated up the competition the next year, 1929, in Arpajon. George Brough himself rode his factory special to 130mph, the ride of his life, but failed to make a return run due to a minor mechanical problem. LeVack had better luck, averaging 207.33kph. That was the last time a normally carbureted motorcycle took the World Land Speed Record, as the big old V-twin engines had could not breathe any harder, and so were forced; the Age of Superchargers had begun.

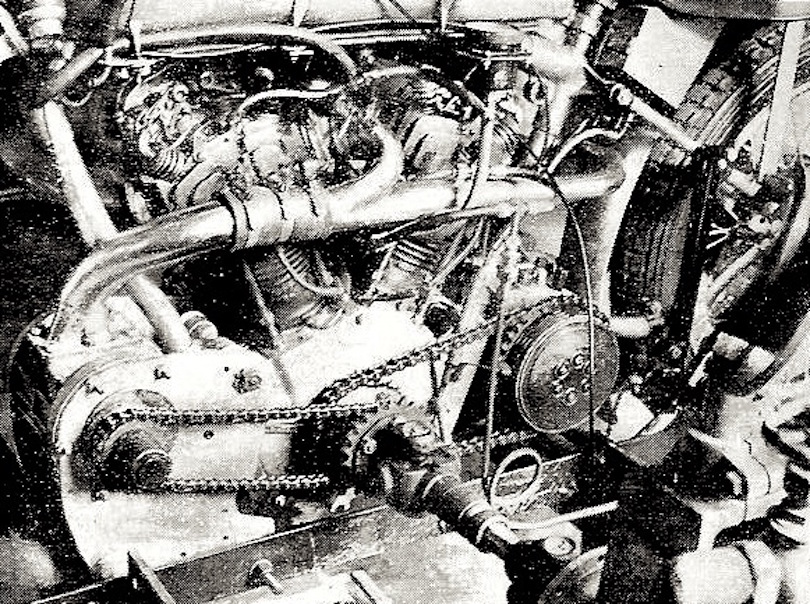

The English builders Zenith, Brough Superior, and OEC all used the same big V-twin JAP engine, and OEC decided to trump their fellow countrymen by attaching a huge blower to their engine, which increased power by 20%, although the science of supercharging was still young; every plumbing modification and carburetion change was an experiment. Still, OEC hauled their new machine, along with fearless racer Joe Wright, to France; Wright piloted the OEC-Temple-JAP to 220.59kph (137.58mph) at Arpajon, a huge leap in speed, which meant everyone else needed a supercharger to play the Speed Record game. Wright’s run was also the first time a rider had officially exceeded Glenn Curtiss’ 1907 speed record…

== THE WAKE-UP CALL ==

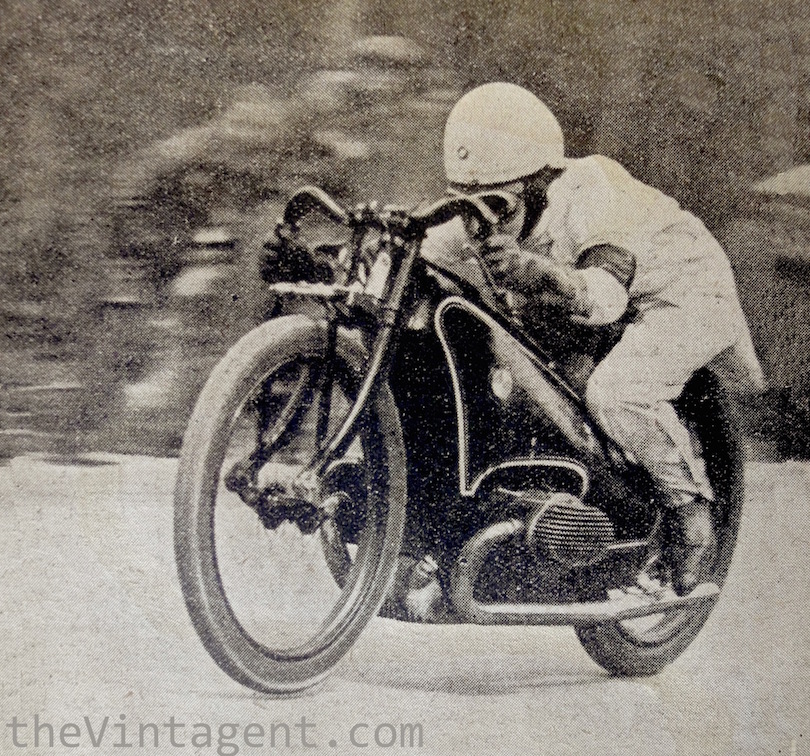

While these three Kings of tiny, dirty, and unheated little English workshops – Brough, Barnes, and Temple – were having a splendid time in their private fight for ‘fastest’ bragging rights (on French soil), they didn’t hear the whine of a supercharged flat-twin blasting along at 221.54kph in Inholstadt, and knocking the British flag over. The English had mistakenly believed their own press and advertising, thinking their dominance of road racing and speed records was almost a natural right, a benefit of their extensive Empire and upper-class privilege, but they weren’t the only ones interested in going fast, and certainly weren’t the only engineers capable of building a really fast motor.

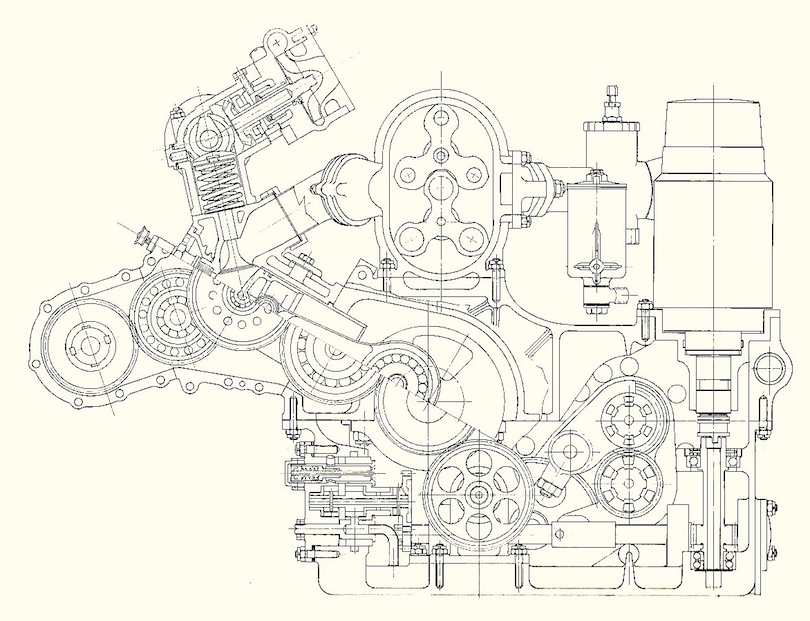

The Absolute World Motorcycle Speed Record, of course, was only one of dozens of speed records available, each based on combinations of time, distance, and engine capacity. Two German factories – BMW and DKW – were busy developing supercharged road-racing motorcycles; BMW since 1927 with a blown OHV 750cc flat twin, DKW since 1925 with their 175cc and 250cc two-strokes, which used ‘extra’ pistons to pump a fuel charge into their crankcases. Like manufacturers everywhere, BMW and DKW wanted to showcase their engineering prowess through racing and record-breaking, a process which accelerated rapidly in the 1930s, as DKW became the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world with its simple but elegant two-stroke roadsters, and fiercely fast supercharged two-stroke racers.

International road racing and record-breaking heated up dramatically in the 1930s, regardless of the economic depression which gripped the industrial world. While English factories like Norton and Velocette developed straightforward and very effective single-cylinder overhead-camshaft racers (the International and KTT, respectively), engineers everywhere understood that an engine which moves air most efficiently, and spins at the fastest rpm, is the engine which produces the most power. Translated into metal, this meant more cylinders, supercharging, and camshafts near the valves for effective management of cylinder airflow. The science of the internal combustion engine had been laid down by English engineers like Sir Harry Ricardo and Harry Weslake, who published their principles for everyone to read, but it seemed the German and Italian translations were the best-thumbed.

Just because the facts are water-clear, doesn’t mean the horse will drink. For whatever reasons, cultural or financial, the English motorcycle industry failed to embrace the challenge presented to them in 1930s international motorcycle sport, and carried on with designs penned in the mid-1920s, right through the death of British GP racing in the 1950s. The biggest English factories – BSA and Triumph – had no factory race teams by 1930, while the biggest German and Italian factories probably spent TOO much money on racing. The British factories who did race (Norton, Velocette, Rudge, New Imperial, etc) had the best engine tuners and chassis designers, with decades of hard experience, who could extract more power and better handling from their reliable single or two-cylinder racers.

== The Scientific Racer ==

The writing was on the wall, and engineers from overseas approached racing motorcycle design from an entirely different perspective, science-based machines designed from first principles, with calculated power outputs and target speeds far beyond what any single-cylinder or V-twin motorcycle could reach. It was only a matter of time before their experiments were successful. The shock of a BMW taking the absolute World Speed Record was a matter of personal, and for the first time, national pride for the English competitors. BMW had only existed as a motorcycle company for 7 years, and was already at the forefront of supercharging technology, having bolted blowers onto their flat twins since 1927. While their supercharged road racers were fast, they didn’t handle that well at the limits, and were no match on any race track with curves against the all-around riding excellence of a Sunbeam TT90 or Norton CS1 or Saroléa Monotube.

The WR750 Henne rode at Ingolstadt to 221.54kph was based on the R63 750cc OHV roadster, using the same tube-frame chassis, with some very special magnesium racing parts. It was partially streamlined, but only to the extent of covering the steering head and some of the bodywork in form-fitting sheet metal. While the overall effect was a bit lumpy, the WR750 was visually a more integrated motorcycle than its cobbled-up competition, because the entire machine was designed inside a single factory, with a set of engineers working to improve their product.

By contrast, their English competition formed an old-fashioned men’s club of jolly sporting gents, who assembled the best components they could buy from industry friends, then worked with racing pals to combine these parts into the fastest possible package, in rented workshops beside the Brooklands track. The cross-Channel competition for World’s Fastest became a battle pitting the Engineers against the Enthusiasts, the professionals against the privateers, the mind versus the heart. Of course, this metaphorical division is illusive; every effort required some mix of inspiration and experiment, but the flavor (or national character?) of our competing teams was distinct. Teams of engineers in Germany working from plans, versus teams of English speed addicts working from intuition and hard-won racing experience. The contrast between these factions became even more stark as the 1930s progressed, as the World Speed Record became a battleground between BMW and Brough Superior-JAP, and the political/propoganda implications of this proxy battle between rival nations grew far more serious.

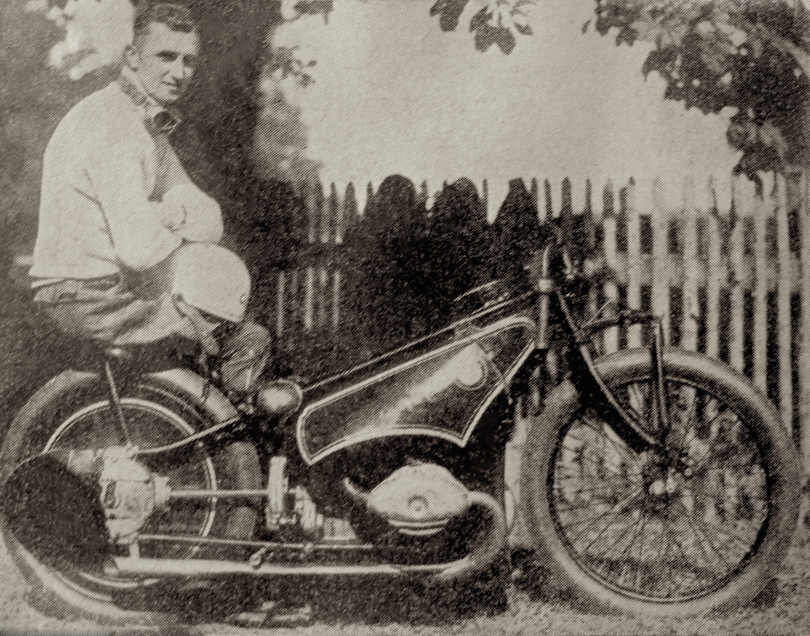

Last of the old-school World Speed Record contenders: ‘Super Kim’, the 1925 Zenith-JAP modified in Argentina with a supercharger and 1700cc motor, seen here at the Vintage-Revival Montlhéry in 2011. A machine I found in Argentina many years ago, and which now lives in Germany.

Curtiss claimed many years later that the speed claimed was just a good bs story for the magazines. Check out the excellent article on this bike in the Sept-Oct 2020 edition of The Antique Motorcycle published by the Antique Motorcycle Club of America.