Top 100 Most Expensive Motorcycles

How do we love thee? Let us count the ways. The Vintagent's 'Top 100 Most Expensive Motorcycles' is the definitive list of most expensive motorcycles sold at public auction. We've been keeping track of the top auction sales since 2006, and if you want editorializing on these prices, you'll have to ask nicely - these are just the facts, ma'am. (Note: Price conversions represent the exchange rate on the day of sale).

Click here to see the Also Rans: the bikes that fell off the Top 100.

Click here to see the World's Most Expensive Private Sales.

Top 100 Most Expensive Motorcycles:

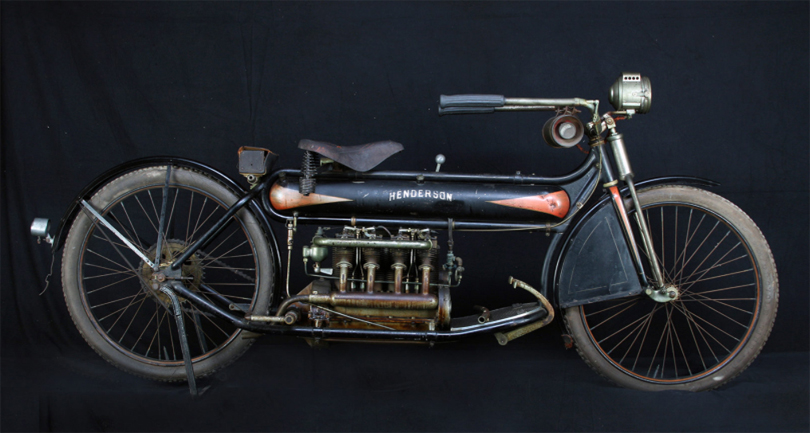

Number 1:

Jan 28, 2023, Las Vegas, Mecum

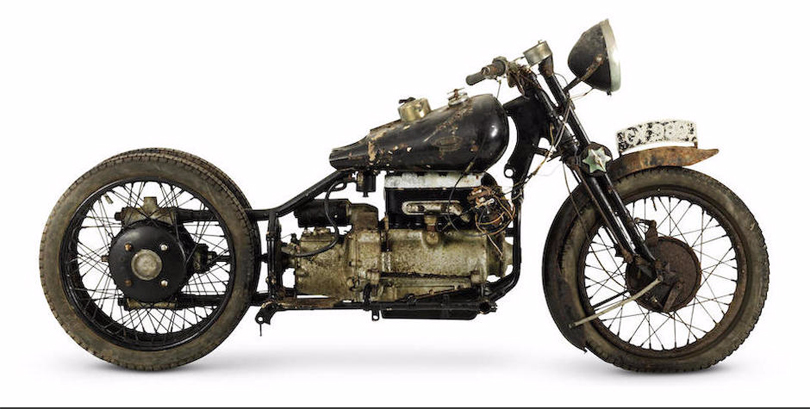

Number 2:

Jan 26, 2018, Las Vegas, Bonhams

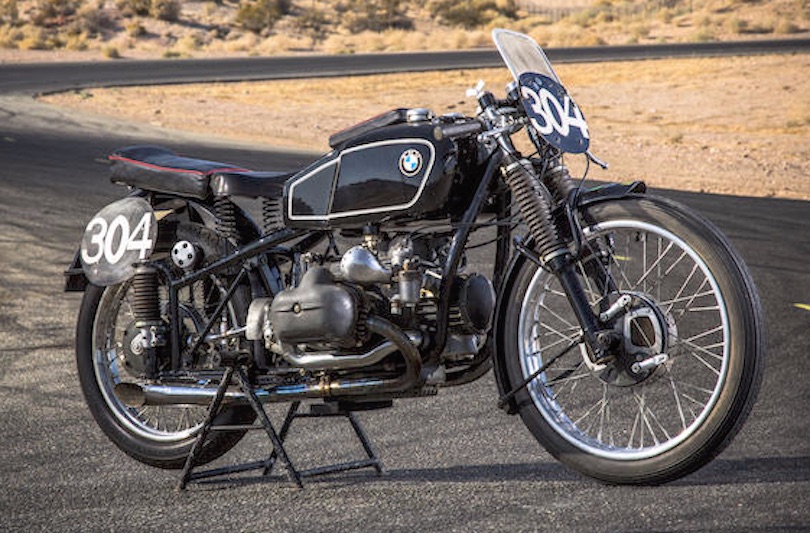

Number 3:

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum Auctions

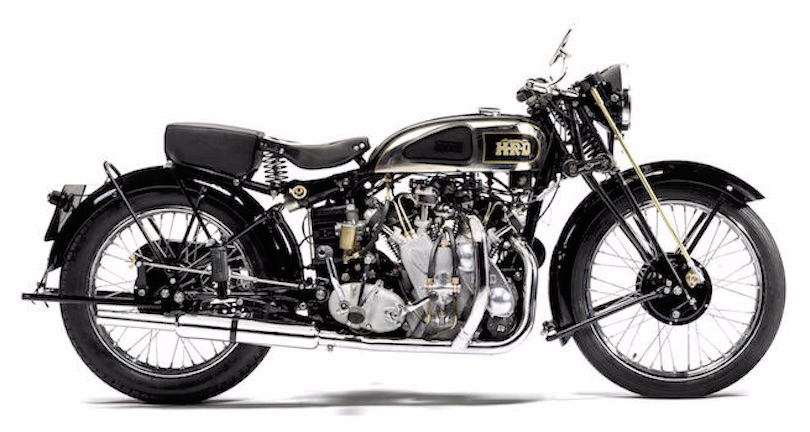

Number 4:

Aug. 2019, Monterey, Mecum

Tied for Number 5:

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Tied for Number 5:

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 6:

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum Auctions

Number 7:

July 2008, Monterey, MidAmerica

Number 8:

Indianapolis 2019, Mecum

Number 9:

Mar. 2019, National Motorcycle Museum, H&H

Number 10:

Jan. 2019, Los Angeles, Heritage Auctions

Number 11:

Nov. 2014, Bond St, Bonhams

Number 12:

Jan. 2017, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 13:

Apr. 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 14:

Jan. 2013, Las Vegas, Bonhams

Number 15:

Oct. 2012, Duxford, H&H Auctions

Number 16:

Oct. 2010, Sparkford, H&H Auctions

Number 17:

Oct. 2012, Battersea, RM Auctions

Number 18:

Jan. 2016, Las Vegas, Bonhams

Number 19:

Apr. 2014, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 20:

Sep. 2015, Melbourne, Shannons

Number 21:

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 22:

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 23:

Apr. 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 24:

June 2021, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 25:

Oct. 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 26:

Apr. 2012, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 27:

Apr. 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 28:

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 29:

Apr. 2013, Imperial War Museum, H&H

Number 30:

Apr. 2013, Imperial War Museum, H&H

Number 31:

Bicester Heritage, Dec. 2020, Bonhams

Number 32:

Apr. 2012, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 33:

Oct. 2008, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 34:

Aug 2016, Monterey, Mecum

Number 35:

Oct 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 36:

Jan. 2015, Kissimmee, Mecum

Number 37:

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 38:

Oct. 2006, Gooding and Co.

Number 39:

Sep. 2008, New Bond St, Bonhams

Number 40:

Oct. 2018, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 41:

Apr. 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 42 (tied):

Oct. 2011, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 42 (tied):

Jan 28, 2023, Las Vegas, Mecum

Feb. 2014, Paris, Bonhams

Number 43:

Oct. 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 44:

Apr. 2022, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 45:

May 2012, Monaco, RM Auctions

Number 46:

Apr. 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 47:

Aug. 2023, Monterey, Mecum

Number 48:

Aug. 2019, Quail Lodge, Bonhams

Number 49:

Sep. 2008, New Bond St, Bonhams

Number 50:

May 2012, Monaco, RM Auctions

Number 51:

Jan. 2020, Las Vegas, Mecum Auctions

Number 52 (tied):

June 2008, Monterey, RM Auctions

Number 52 (tied):

Aug. 2023, Monterey, Mecum Auctions

Number 52 (tied):

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum Auctions

Number 53 (tied):

Aug. 2012, Quail Lodge, Bonhams

Number 53 (tied):

Aug. 2012, Quail Lodge, Bonhams

Number 54:

Apr. 2022, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 55:

Jan. 2012, Las Vegas, MidAmerica

Number 56:

May 2021, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 57:

Apr. 2008, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 58:

Aug. 2012, Quail Lodge, Bonhams

Number 59:

Apr. 2000, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 60:

Feb. 2016, London, Coys

Number 61:

Apr. 2019, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 62:

Jan. 2011, Las Vegas, MidAmerica

Number 63:

Nov. 2006, Los Angeles, Bonhams

Number 64:

June 2009, New York, Antiquorum

Number 65:

Apr. 2019, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 66:

Apr. 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 67:

Sep. 2008, New Bond St, Bonhams

Number 68:

Jan. 2014, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 69:

June 28 2015, Julien's Auctions, Los Angeles

Number 70:

Apr. 2010, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 71:

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 72:

October 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 73:

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 74:

January 2007, Las Vegas, MidAmerica

Number 75:

Jan 2020, Las Vegas, Mecum Auctions

Number 76:

Jan. 2011, Las Vegas, MidAmerica

Number 77:

Apr. 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 78 (tied):

Oct. 2006, Gooding and Co.

Number 78 (tied):

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 78 (tied):

Jan. 2022, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 79:

January 2008, Las Vegas, MidAmerica

Number 80:

Oct. 2010, Haynes, HandH

Number 81:

Jan. 2022 Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 82:

Dec. 2021, Los Angeles, Bonhams

Number 83 (tied):

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 83 (tied):

July 2020, Indianapolis, Mecum

Number 84:

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 85:

January 2015, Las Vegas, Bonhams

Number 86:

Oct. 2018, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 87:

April 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 88 (tied):

Jan 2023 Las Vegas Mecum Auctions

Number 88 (tied):

Jan 2023 Las Vegas Mecum Auctions

Number 88 (tied):

May 2021, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 88 (tied):

May 2021, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 88 (tied):

Jan. 2020, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 88 (tied):

Jan. 2020, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 88 (Tied):

Jan. 2019, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 89:

Jan. 2020, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 90:

April 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 91:

Dec. 2022, Matthews Auctions

Number 92:

Oct. 2018, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 93:

April 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 94 (tied):

Jan. 2022, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 94 (tied):

Jan. 2022, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 95:

Aug. 2012, Quail Lodge, Bonhams

Number 96:

April 2016, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 97:

Jan. 2020, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 98:

October 2015, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 99:

January 2017, Las Vegas, Bonhams

Number 100:

April 2006, Stafford, Bonhams

Number 101 (tied):

May 2021, Las Vegas, Mecum

Number 101 (tied):

Mar. 2015, Las Vegas, Mecum

To see the 'also rans' formerly in the Top 100, Click here!

Paul d'Orléans is the founder of TheVintagent.com. He is an author, photographer, filmmaker, museum curator, event organizer, and public speaker. Check out his Author Page, Instagram, and

Paul d'Orléans is the founder of TheVintagent.com. He is an author, photographer, filmmaker, museum curator, event organizer, and public speaker. Check out his Author Page, Instagram, and

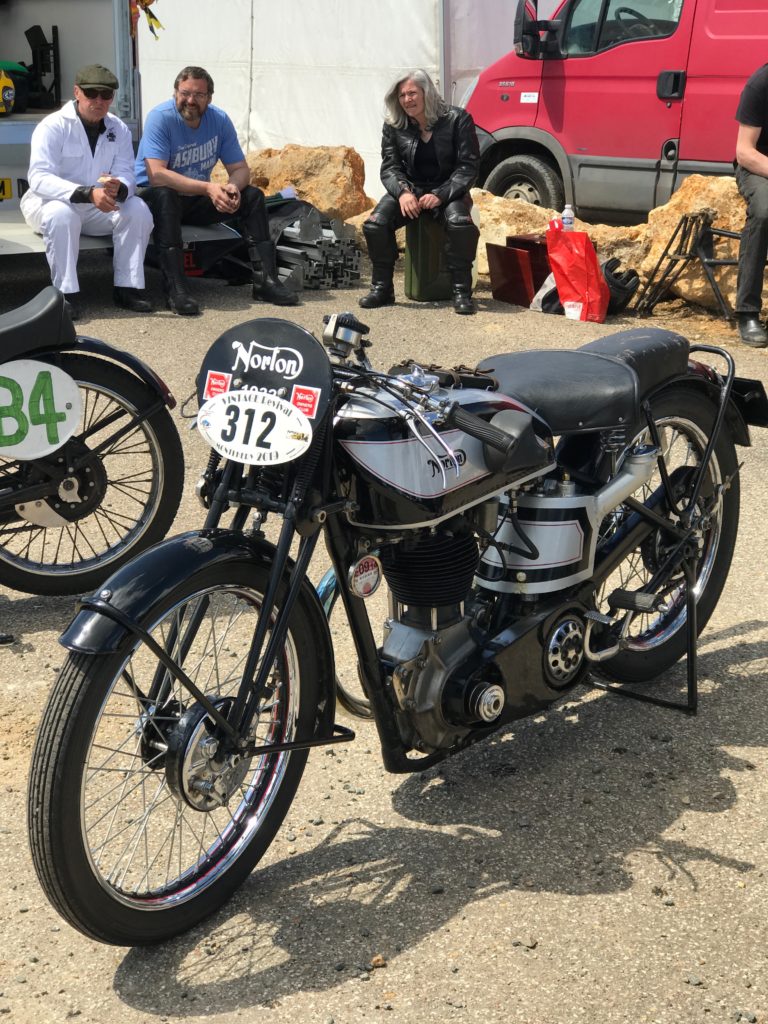

Vintage Revival Montlhéry 2019

Vintage Revival Montlhéry is a bi-annual event for pre-1940 cars, motorcycle, and bicycles at the famous banked concrete track about 20 minutes south of Paris. It's the only original 1920s banked race track still in use, as all the wooden tracks are long gone, and the rest are destroyed or no longer in use, like the Sitges motordrome on Spain, and the rotting banked oval at Monza. The Autodrome de Linas Montlhéry opened in 1924, as the brainchild of industrialist André Lamblin, who purchased the forested acreage and hired engineer Raymond Jamin to design the track.

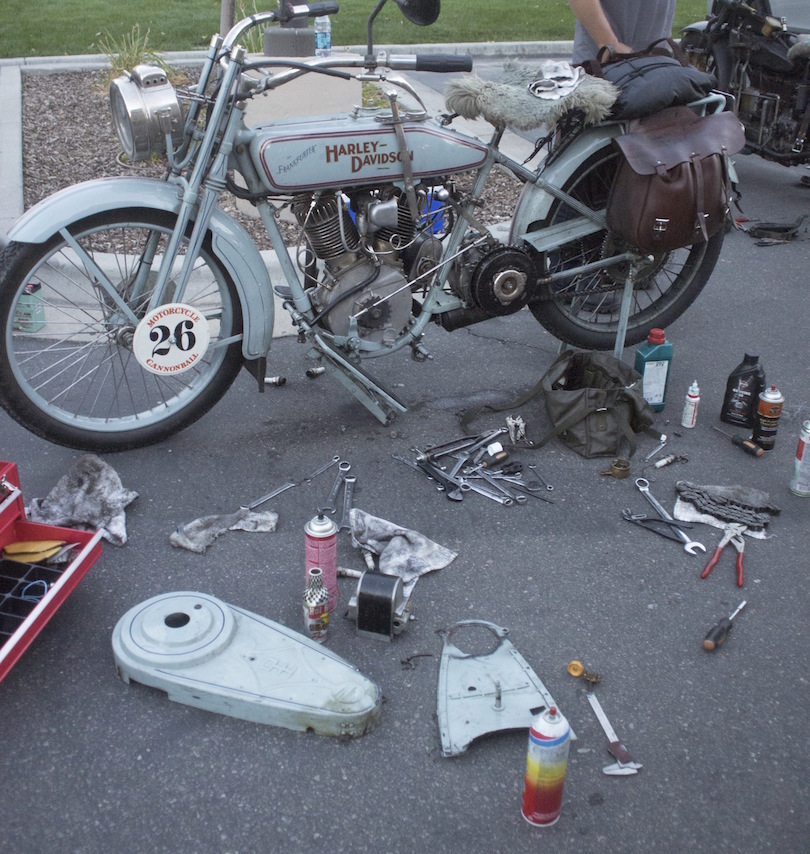

Cannonball: Into the West

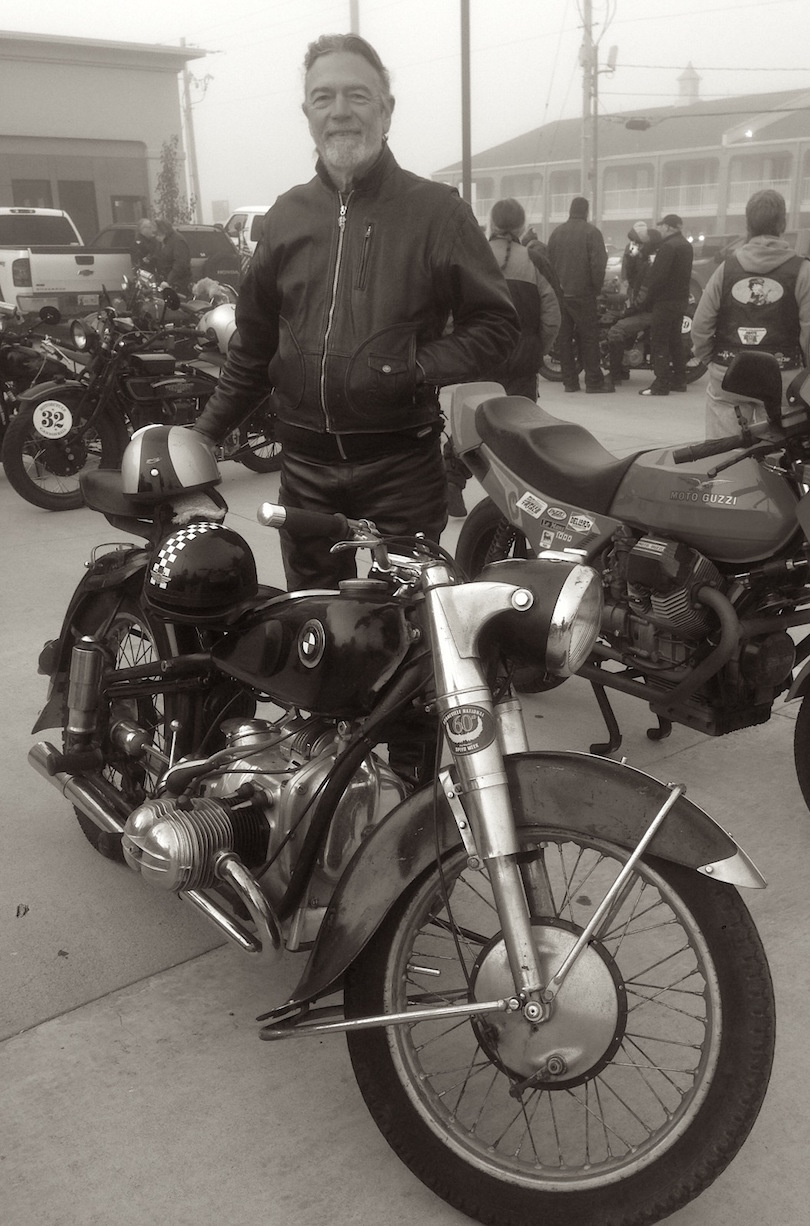

While there’s complication in keeping an 80-year old motorcycle running all day during the Cannonball, the landscape of America provides a calming counterbalance, as it's absorbed in slow motion from one coast to the other.

For the Cannonball riders, every mile held fascination and variety, as the landscape shifted from the Florida swamps, to the Georgia farms, the Tennessee and Kentucky woodlands, the Missouri and Kansas prairies, the enormous mountains of Colorado, the red canyons of Utah, Nevada’s harsh and treeless desert, Idaho’s rolling hills and hidden canyons, and Washington’s vineyards and volcanoes.

An examination of our country at such a pace allows for a full range of celebration and indictment, for while there was never a mile of nature I would have missed - even the long stretches of Nevada’s forbidding dryness - the footprint of America’s inhabitants varies from placid farmlands and charming small towns, to ugly and identical strip malls, a constant refrain of Wal-Marts, boring suburbs, and the shocking blight of near-abandoned cities like Cairo Missouri. We were given bottled water at one hotel, and warned the tap water was unsafe to drink because of nitrates from farming; in other towns, chemical residue from fracking had poisoned the water, and I wondered if the seemingly innocent pleasure of riding an 80+ year old bike across the country was actually a costly luxury.

Make of it all what you will, but we’ve seen a 4000-mile swath of the country, in all its mixed glory. The pockets of inane suburbia were dwarfed by the enormity of the country’s natural beauty, which only grew as we chugged westward, into the great, uninhabited swaths of Colorado and beyond. I was unfamiliar with landscapes further eastward, the tobacco barns, humid wetlands, and sugary lilt of waitresses in the South, and the beautiful geometric Amish barn-murals as far west as Kansas. Each rider yearned to spend more time in some charming spot or other, to hang around a bit longer on two wheels, but we all suffered the Cannonball Curse: a 17-day parade of interesting places, with no time to explore.

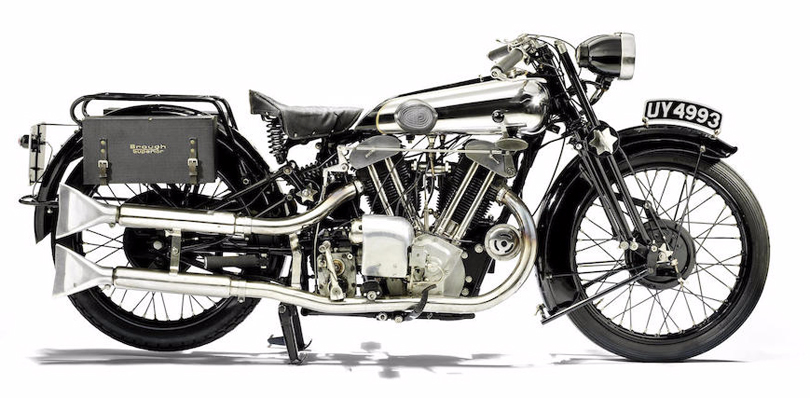

My 2014 Cannonball was the opposite of my 2012 ride, which was a sandwich of struggle and heartbreak, with a glorious 1000-mile ride on my Velocette KTT in the middle. This year, I’d arranged a partnership with Alan Stulberg of Revival Cycles of Austin, who took care of prepping our borrowed 1933 Brough Superior 11-50 (many thanks to Bryan Bossier of Sinless Cycles for the loan), plus cross-country transport and support, in the form of mechanic Chris Davis. Thus, I was relieved of mechanicking to concentrate on riding the Brough responsibly, an onerous task given its capabilities. Whatever reputation British motorcycles may have acquired for unreliability and fragility simply didn’t apply to the Brough, which was a rock. George Brough blew a lot of smoke, but there’s fire in his handiwork, and the consensus among Cannonballers was surprised respect; it was clearly the most all-around capable machine on the rally.

Which isn’t to denigrate the seven 1936 Harley EL Knuckleheads on the Cannonball, none of which experienced significant trouble, and most of which received perfect scores by Tacoma. I was offered a 240-mile ride over the Rockies on Matt McManus’ lovely blue/white Knuck, and it traversed the two 11,000’+ passes with aplomb, roaring across them at 60mph. The handling wasn’t as sure-footed as the Brough, but it was difficult to parse the square tires from the quality of the chassis. It took determination to heel the beast around hard bends, and is the only bike I’ve ever had to wrestle the bars in a steering – as opposed to counter-steering – manner. I came away impressed that Matt rides his machine so quickly through the bends, as even this corner-scratcher would be more circumspect. The engine, though, was willing and smooth, revving freely and feeling perfectly modern.

Quite a few bikes made all the miles, 32 in total, which included four ‘Class I’ bikes of 500cc, from the ’24 Indian Junior Scout of Hans Coertse (from South Africa, and the eventual Grand Prize winner), to a ’31 Moto Guzzi Sport (Giuseppe Savoretti from Italy), a 1932 Sunbeam Model 9 (ridden by Kevin Waters, with an engine built by Chris Odling of Scotland), and the BMW R52 owned by Jack Wells and ridden by Norm Nelson. Other Class I bikes struggled with the enormity of America, and gave bother, including a marque one might assume a cake-walk; early BMW’s have never had an easy run with the ‘Ball, and two retired completely before the first week had passed, while others found creative ways to lose mile points. The middle category, Class II, was dominated by Harley J series machines, which made up the bulk of the Cannonball entry. A litany of complaints prevented them swamping the leaderboard, as broken conrods and melted pistons, even a catastrophic fire, took a toll on their numbers.

The four-cylinder brigade of Hendersons, Excelsior-Hendersons, and Indians did well, and all were still running by the end. The big boys, Class III, generally did well, and had an easier time of the rally, being faster and more comfortable than the 1920s-era machines, yet cruised with their 1920s brethren at 50mph out of self-preservation. Riders of slower machines experienced a different rally, being unable to pass vehicles up big hills, and suffering the wake of large trucks as they hammered past; a slow ride is a patient ride, and vulnerable, but faster traffic (not that we encountered a density of cars) proved ultimately safe.

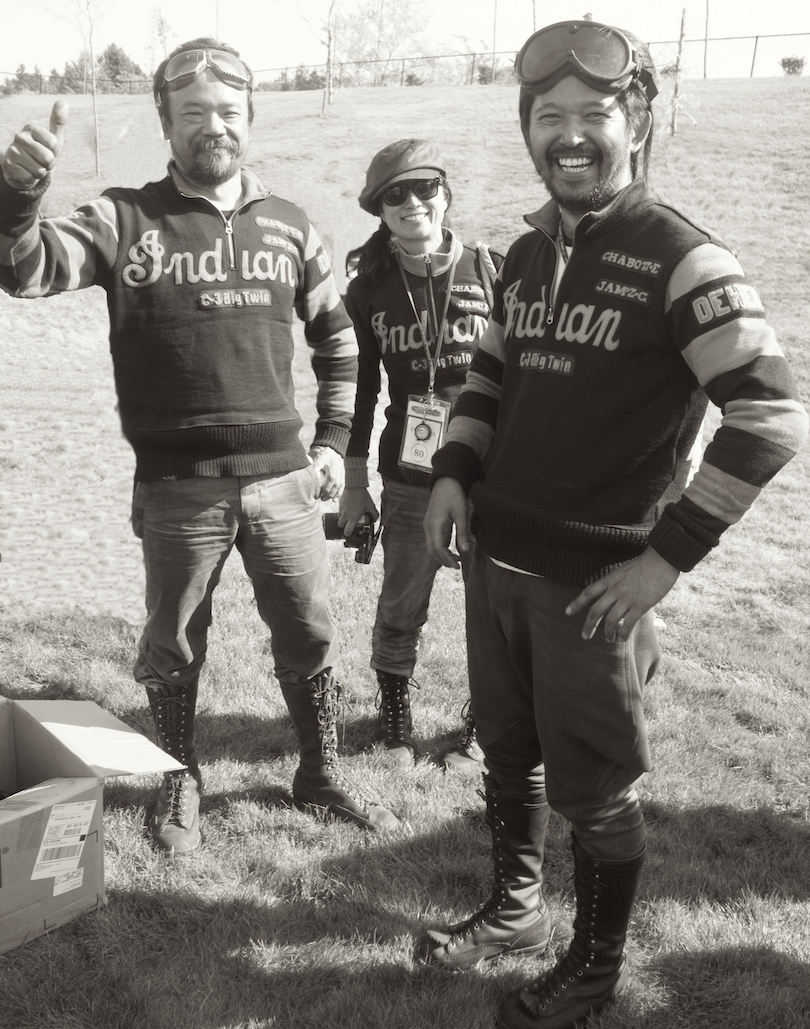

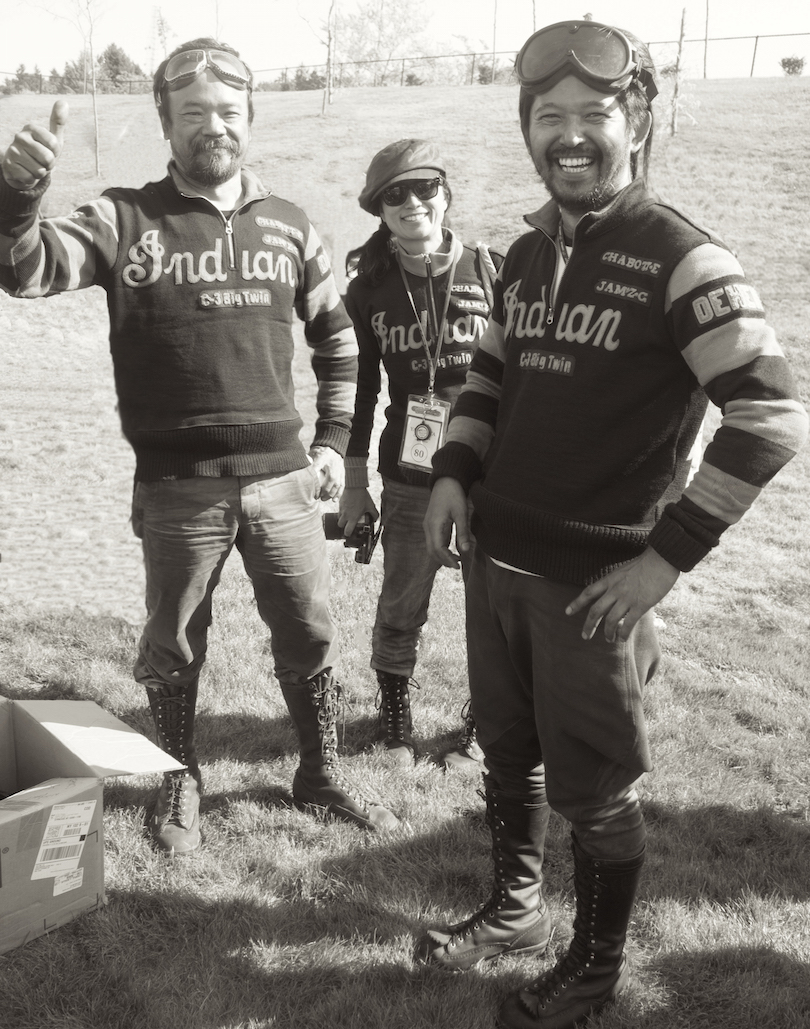

As our Rally Master, John Classen, was unable to make the final banquet, I was asked to emcee the prizegiving ceremony, in which all rivalries were set aside for noisy celebration. As mentioned, Hans Coertse won the big prize with his pretty ‘24 Indian Junior Scout, which he described as having two speeds – 35mph or 45mph, and that’s how he crossed the country. Perhaps the most significant prize, regardless of points or mileage, went to the Japanese team of Shinya Kimura, Yoshimasa Niimi, and Ayu Yamakita, the only team using the same machine in all 3 Cannonballs, their 1915 Indian, which has become a rolling accretion of unusual mechanical compromises and artful fixes, changing daily as the next 100 year old part broke or vanished beside the highway. For all their persistence, they received a standing ovation, and the Sprit of the Cannonball award. Well deserved.

t's difficult to express the vastness of the America landscape in photos, but this gives a clue

Picturesque ruins in eastern Utah, before the canyonlands, but after the mountains of Colorado

A welcome, if unusual, sight at the top of Chinook Pass in Washington: the 1923 Neracar of Martin Addis

'Morticia', the ex-wall of death '29 Indian 101 Scout, with a wheelbase shortened by 4", and her owner Ryan Allen

Some of Colorado's autumn splendor, and a few Knucks to boot (plus Fred Lange's special OHV JDH)

Our German and Polish guests relax in the vineyards of Washington

The 1933 Brough Superior 11.50 and a grain silo, in the canyons of eastern Washington state

The red canyons of Utah offer an exceptional riding terrain – with a lot of groomed red dirt roads. The Brough didn’t seem to mind.

“But for me, that endless blacktop was my sweet eternity.” The Loveless

Any vintage BMW owner has considered Todd Rasmussen at some point during a restoration or rebuild…here with his ex-Bulgarian BMW R51/2

Two bikes, one team; Alan Stulberg on the Brough, and me on Matt McManus' Harley Knucklehead

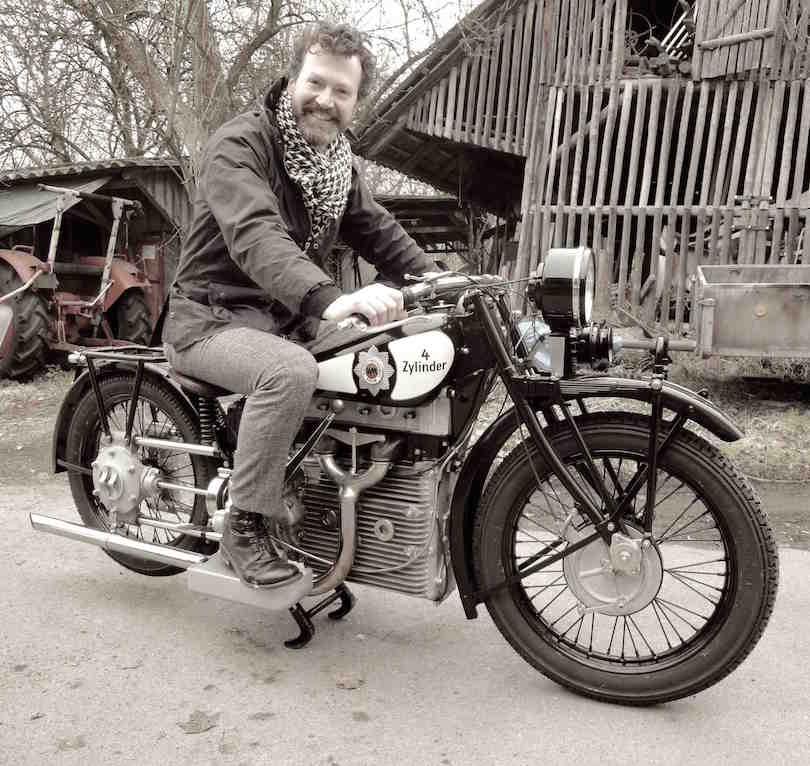

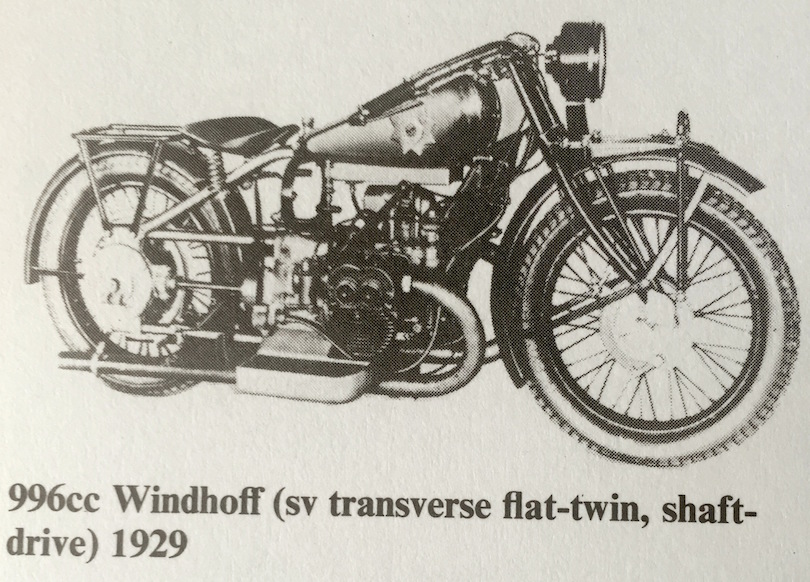

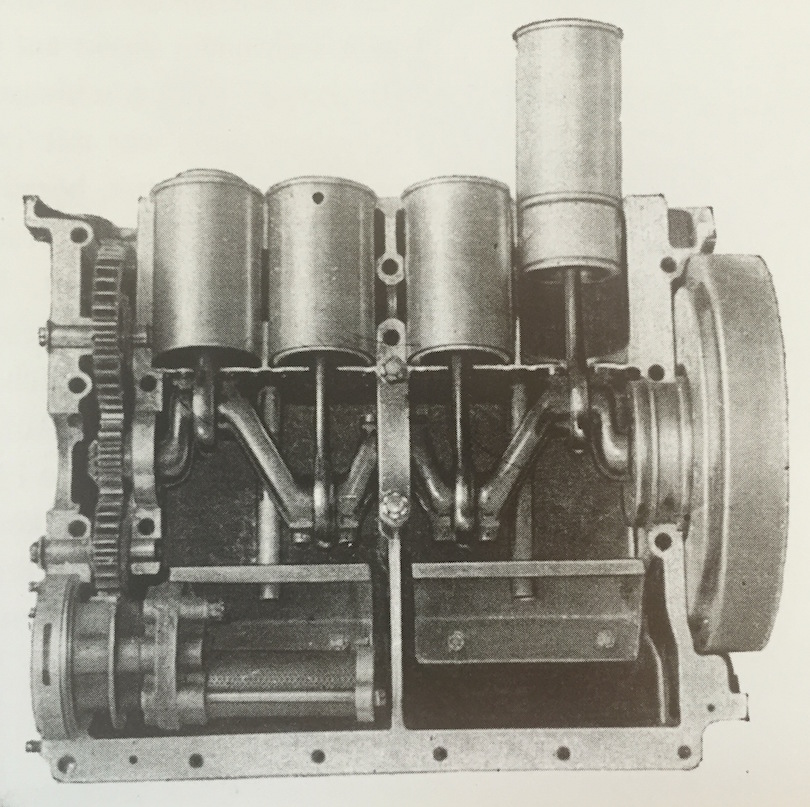

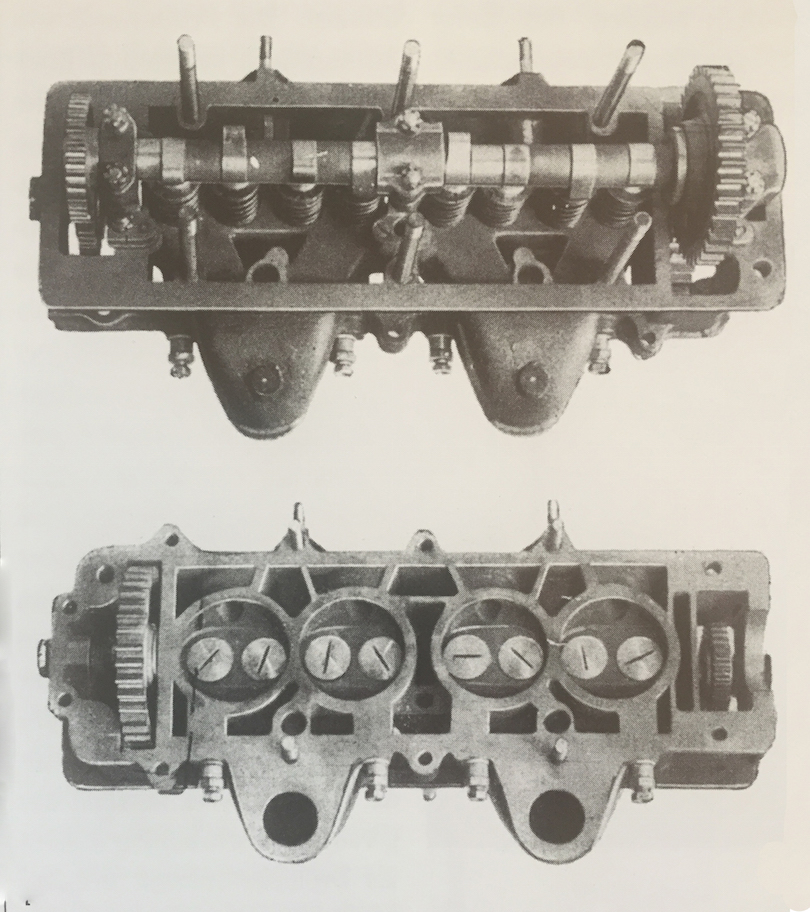

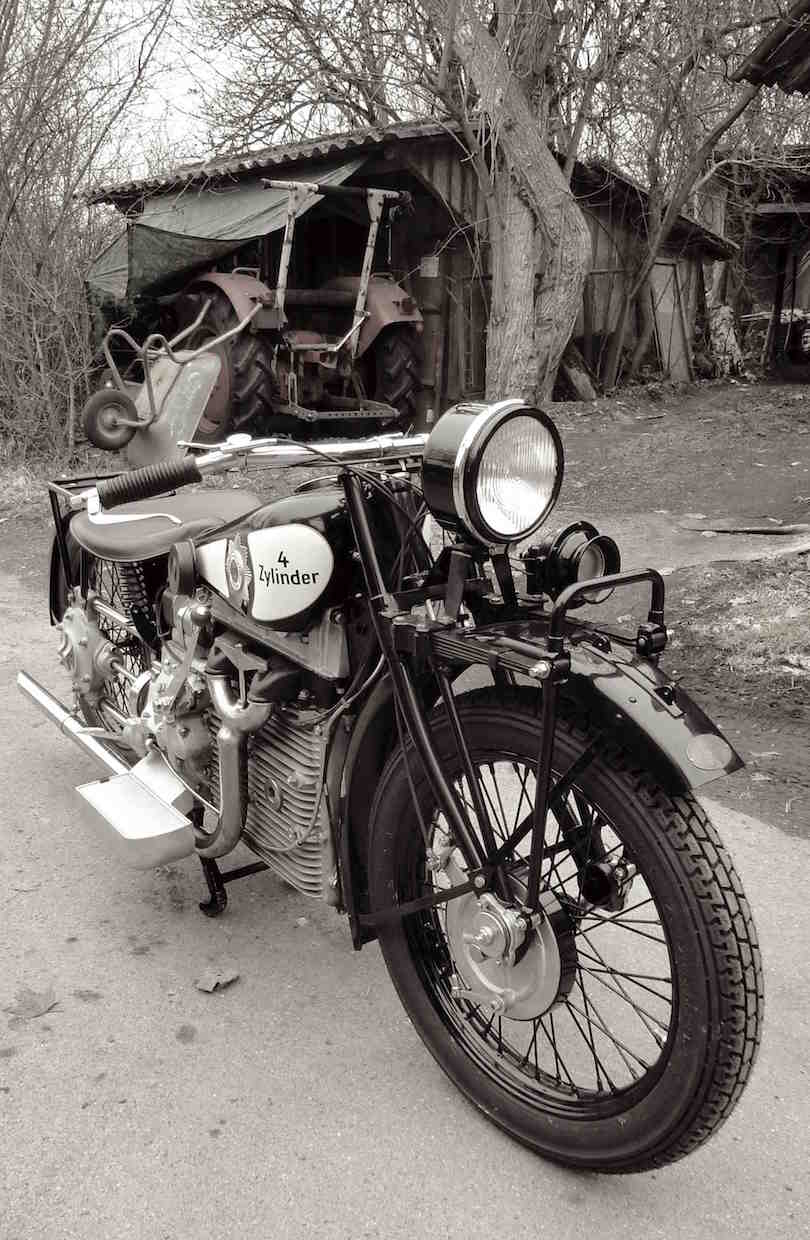

Road Test: 1928 Windhoff

The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world's rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

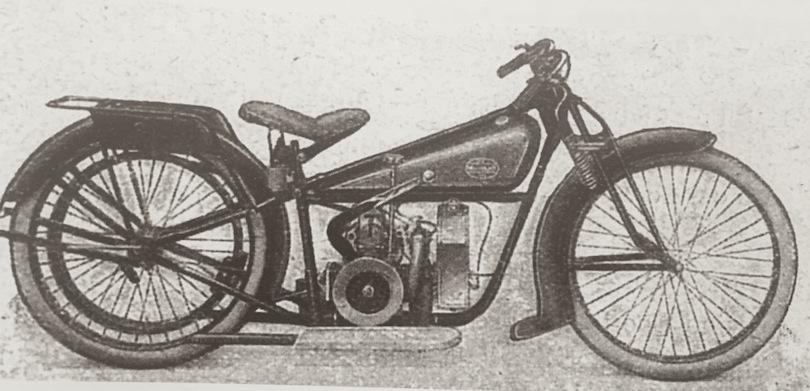

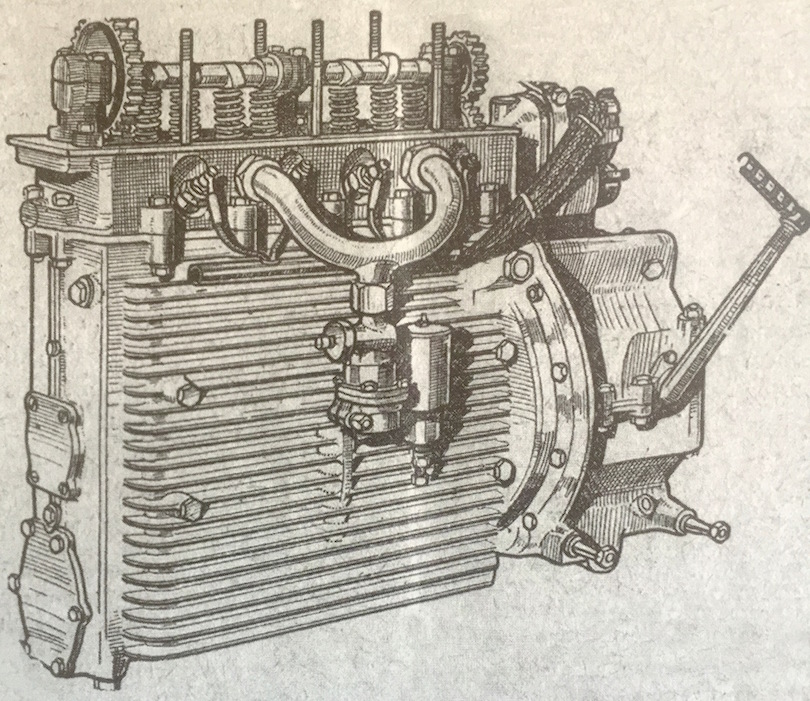

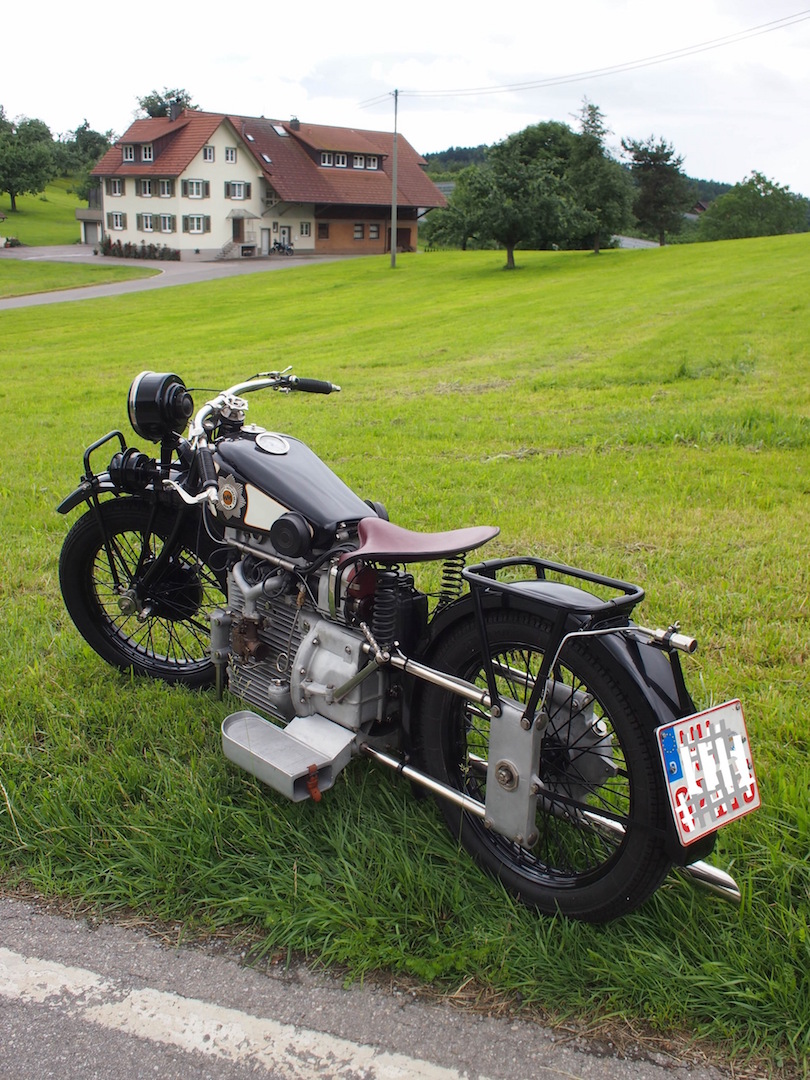

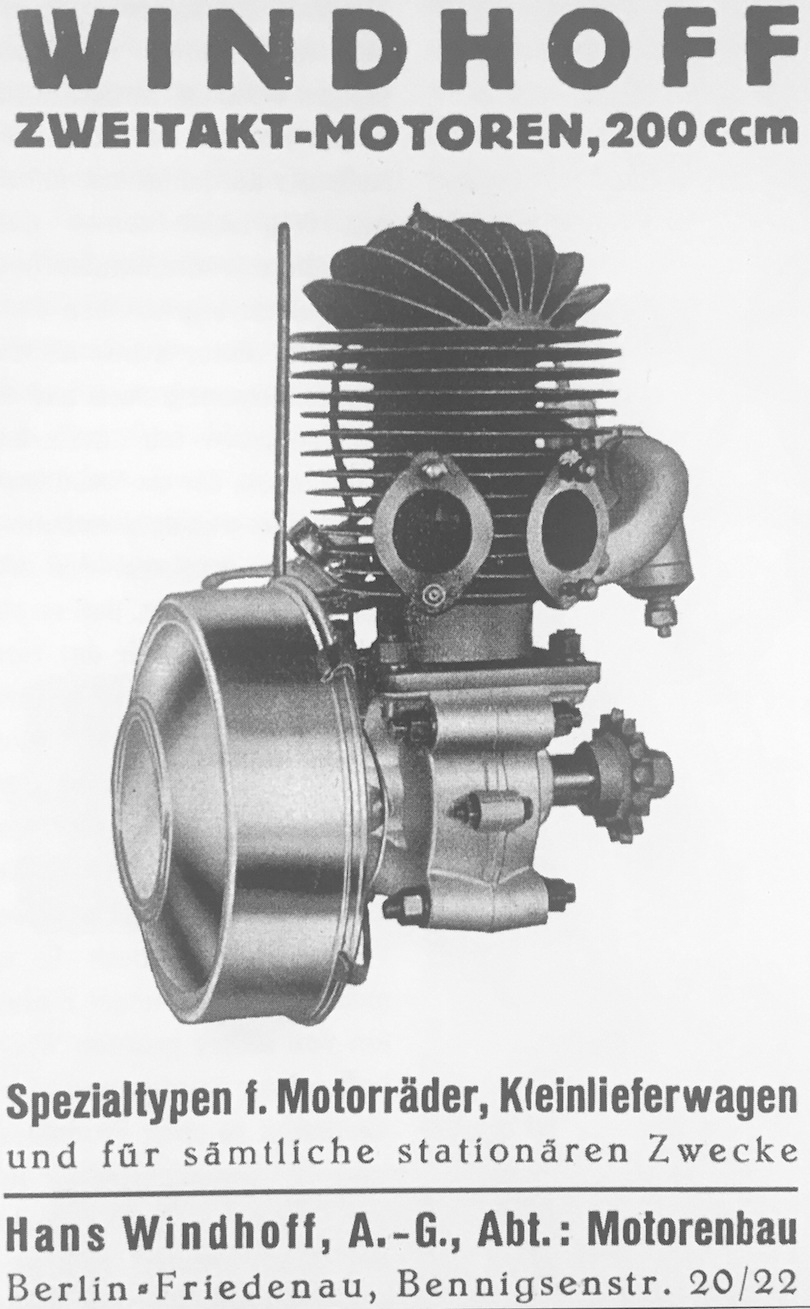

The creations of Hans Windhoff began in Berlin with radiator production for cars, trucks, and aircraft. In 1924, he entered the burgeoning motorcycle market with water-cooled two-stroke machine of 125cc - an excellent although expensive creation, with the engine built under license from a design by Hugo Ruppe, whose ladepumpe (an extra piston used as a supercharger to compress the fuel/air mix) design was used most successfully by DKW in their GP bikes.

Absolute Speed, Absolute Power Pt. 1

A Short History of World Motorcycle Speed Records, 1896-1930

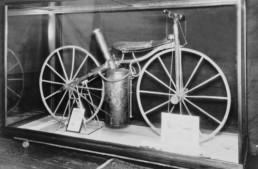

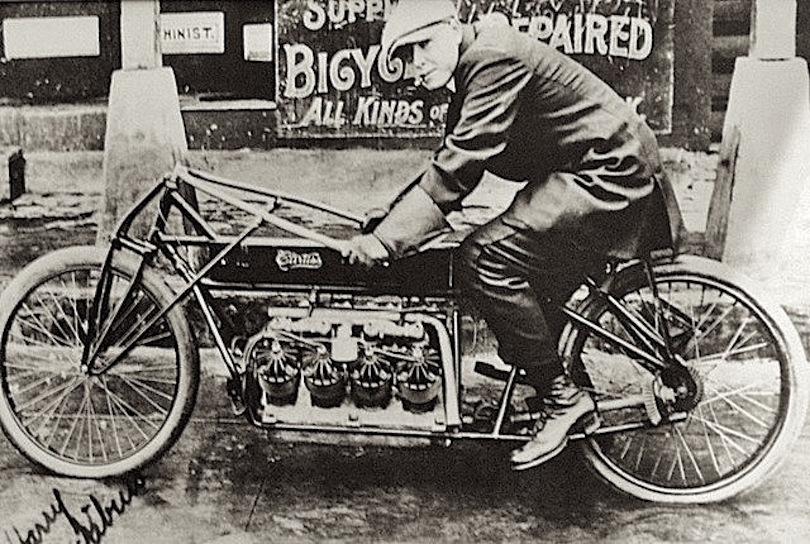

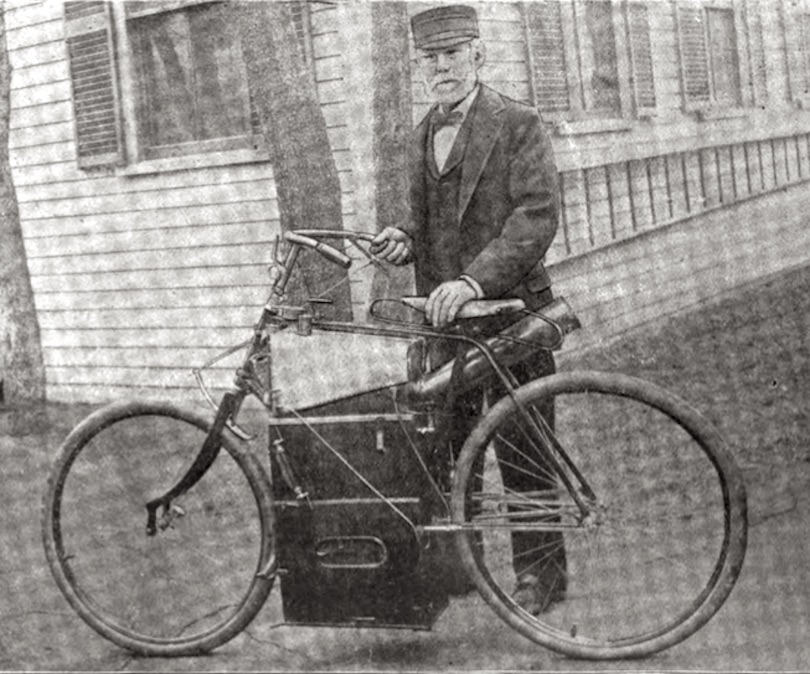

When Sylvester H. Roper attached a small steam engine to an iron-frame ‘boneshaker’ bicycle near Boston in 1867, one question burned in his mind; How fast will it go? I have no doubt Guillame Perreaux asked himself the same question in Paris that same year, when he also attached a steamer to one of Pierre Michaux’s pedal-velocipedes. But it was Roper who was motorcycling’s first speed demon, and its first martyr. Every Café Racer on planet earth should affix to their bike a lucky charm with Roper’s visage. Forget St.Christopher - he never rode a bike; Roper is the true patron saint of motorcycles, and he died for the same sin which stains 21st Century bikers - the lust for speed.

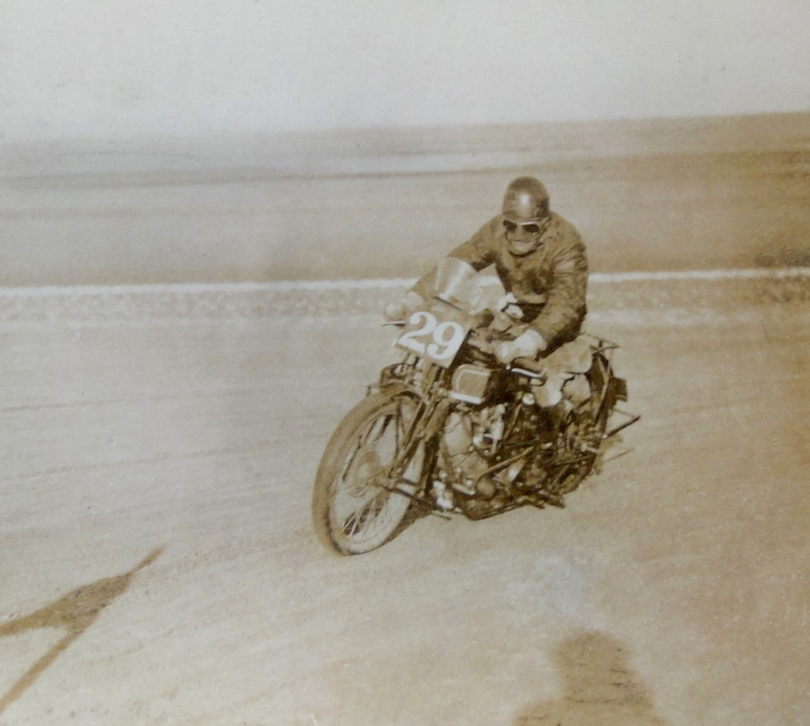

On June 1st, 1896, at the tender age of 73, Roper was asked to demonstrate his ‘self propeller’, as he called it, on the Charles River Speedway, a banked wooden bicycle racing track in Cambridge, Mass. Roper’s steam cycle had a reputation around Boston as the fastest thing on wheels, being able to “climb any hill and outrun any horse”, as he stated. He was invited to pace a few bicyclists at the Speedway, which became a race, and Roper kicked their asses with the 65kph speed of the steamer. Track officials urged him to unleash the hissing beast, and the septugenarian inventor was excited to oblige. After a few scorching laps, Roper was seen to wobble and slow towards his ‘pit crew’ - his son Charles – into whose arms he collapsed, dead. Roper did not crash, but likely had a heart attack from the excitement. Roper became the first motorcycle fatality…not from a wreck, but from the thrill. He deserves a sprocket-edged halo.

== Burning Daytona Sands ==

Glenn Curtiss inherited Roper’s lust for speed. As one of the earliest motorcycle manufacturers in the US, he’d caught the racing bug first on bicycles, then attached an E.R. Thomas motor to his bicycle in 1899, which he called the ‘Happy Hooligan’ (yes, our great-grandpa was cool). Curtiss thought the Thomas engine, which copied Comte DeDion’s design, was crap, so he built his own motor. Curtiss was a mathematical and engineering genius since his childhood, and his engines were reliable and performed better than anything else when introduced in 1905. Curtiss engines were so good he caught the eye of the fledgeling aviation industry, and began supplying motors for dirigibles. But Curtiss was more than an engineer; the question ‘how fast?’ burned bright in his soul, so in 1906 he constructed a spindly motorcycle frame around his V-8 dirigible motor, and travelled to Florida to test his monster on the only speed venue in the US; Daytona/Ormond beach.

Timed runs on the sand were conducted with cars and motorcycles, and Curtiss waited until the end of the day’s 'normal' speed runs, with ordinary production bikes, before wheeling out his 40hp Behemoth. He promptly scorched through a 1-mile trap at 136.3mph - the fastest speed of any powered human to date. His 'return' run was ruined by the disintegration of the direct shaft drive to the rear wheel (no surprise, with a sand bath for the exposed universal joint) and the rear wheel locked at 130mph, while the drive shaft flailed away at the rider... but Curtiss' considerable racing experience won out, and he hauled the beast to a stop without crashing. A true American hero.

With time, the FIM was created to supervise Speed Records, and the first ‘official’ FIM ratified speed was taken again at Daytona beach, when Gene Walker pushed his Indian Chief to 104.12mph in 1920. That was the last time an American flag flew over the World Motorcycle Speed Record for 70 years. For their own reasons, American motorcycle manufacturers, who built the technical equal of any bike in the world through the 1920s, virtually disappeared from global motorcycle competition after 1923, when Freddie Dixon took 3rd at the Isle of Man TT on an Indian 500cc sidevalve single. America turned inward, to its own style of dirt-track racing, and the World Speed Records of the 1920s belonged exclusively to the British.

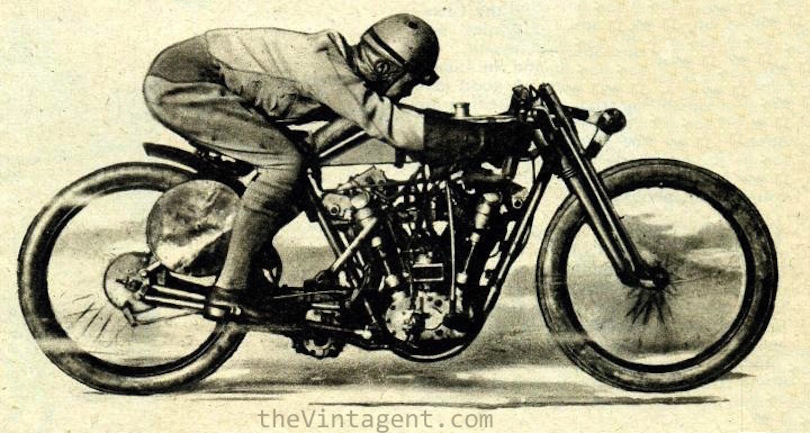

In 1923 Bert LeVack took a frame built by Claude Temple, stuffed it with a mighty 996cc DOHC Anzani engine, and bumped along at Brooklands, half airborne on the notoriously bumpy track. LeVack averaged 108.41mph, and the FIM didn’t have to cross the Atlantic again for motorcycles until the 1950s, when Bonneville became the location of choice for speed-mad riders.

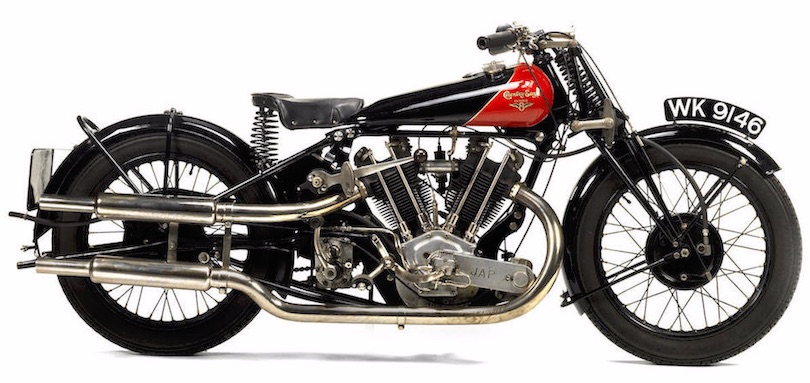

== ALL ENGLAND, ALL THE TIME ==

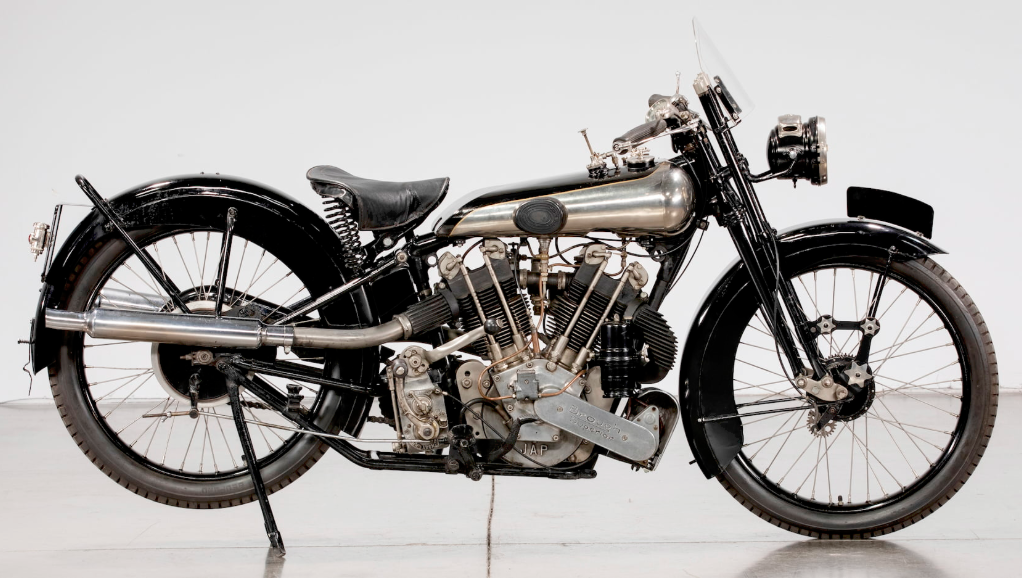

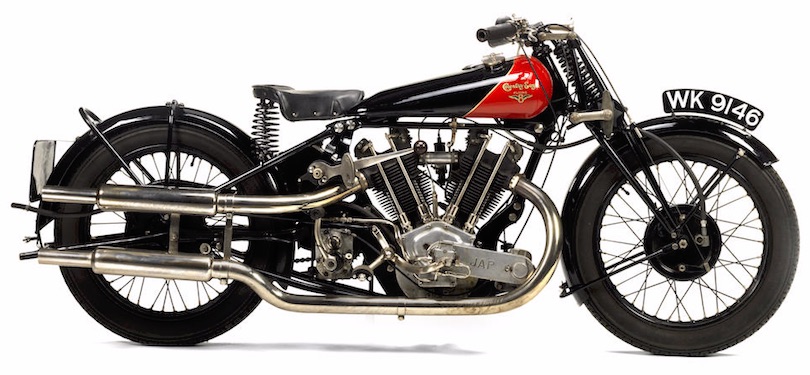

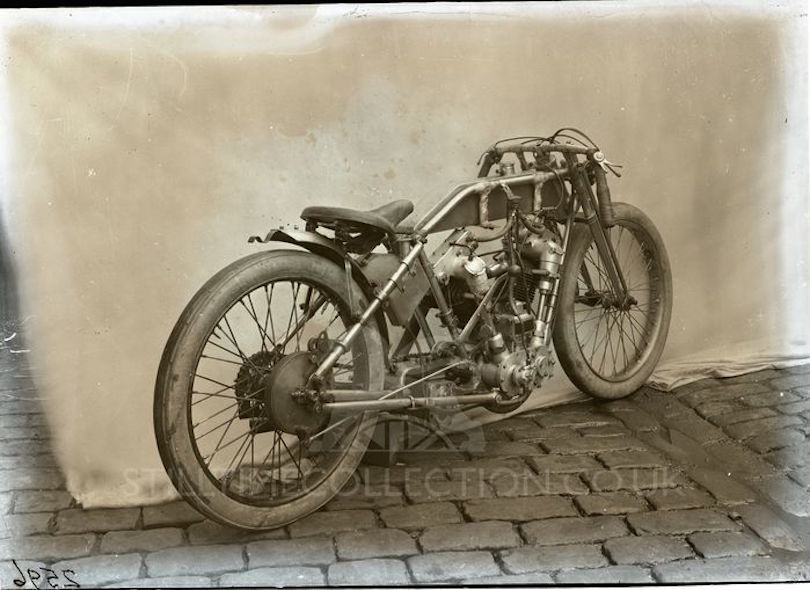

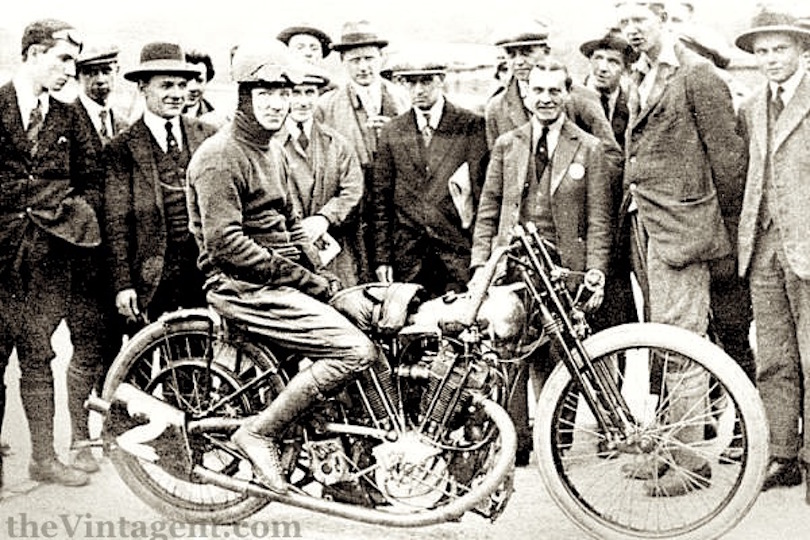

The rest of the 1920s was a fistfight between three tiny English workshops, sometimes called manufacturers, who all used JAP overhead-valve V-twin engines, and progressively made them faster. The hunt began for a new place to go really fast, as Brooklands was fine for racing, but horrible for speed records. A decent straightway was found near Paris, in the village of Arpajon, the future site of the Montlhéry speed bowl. The Arpajon road is still there and still very straight; if you got lost on your way to the Café Racer festival at Montlhéry, you probably took the very same road…but sadly, the roaring racers have long since been replaced by honking commuters.

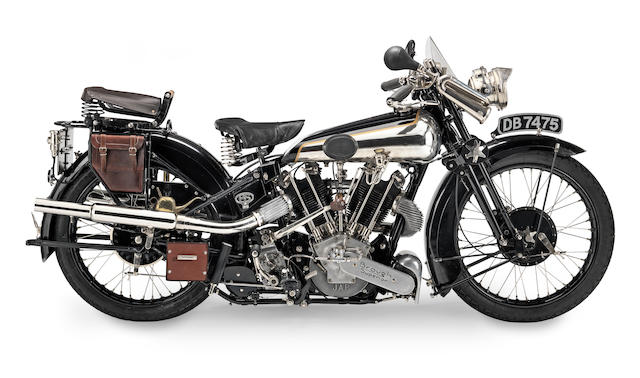

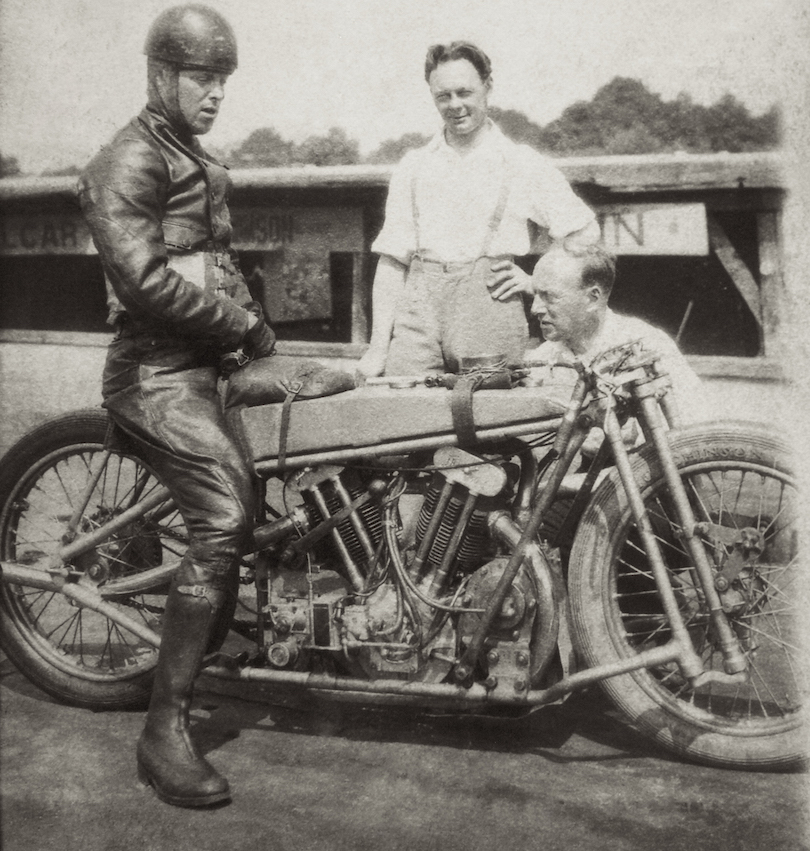

The immortal Bert LeVack became JAP’s racing engineer in the early 20s, and was hired by Brough Superior in 1923 for a new attempt on the World Speed Record at Arpajon, which succeeded at 118.98mph (or since it was in France, 191.59kph). Claude Temple wasn’t happy to have lost the record to George Brough, an egotist with no real racing experience, so Temple teamed up with the Osborne Engineering Company (OEC), who had unusual ideas about chassis design and steering systems (their nickname was ‘Odd Engineering Contraptions’). The OEC speed-record racer used a complicated ‘duplex’ front end, which was heavy and didn’t like turning corners – perfect for a Speed Record. Temple used a special 996cc JAP engine to re-take the record at Arpajon in 1926, averaging 195.33kph.

Freddie Barnes, the owner of Zenith Motorcycles, sold the only proper road-racing motorcycles out of all the English factories competing for Speed Record honors. While Brough Superior was flashy and self-promoting, and OEC was preoccupied with bizarre ideas, Zeniths were busy taking more ‘Gold Stars’ for 100mph laps at Brooklands than any other marque, and the tall, lanky Freddie Barnes was their guru. In 1928, he hired Oliver Baldwin, a Brooklands regular, to ride his 996cc KTOR JAP-engined Zenith to finally break the 200kph barrier, at 200.56kph.

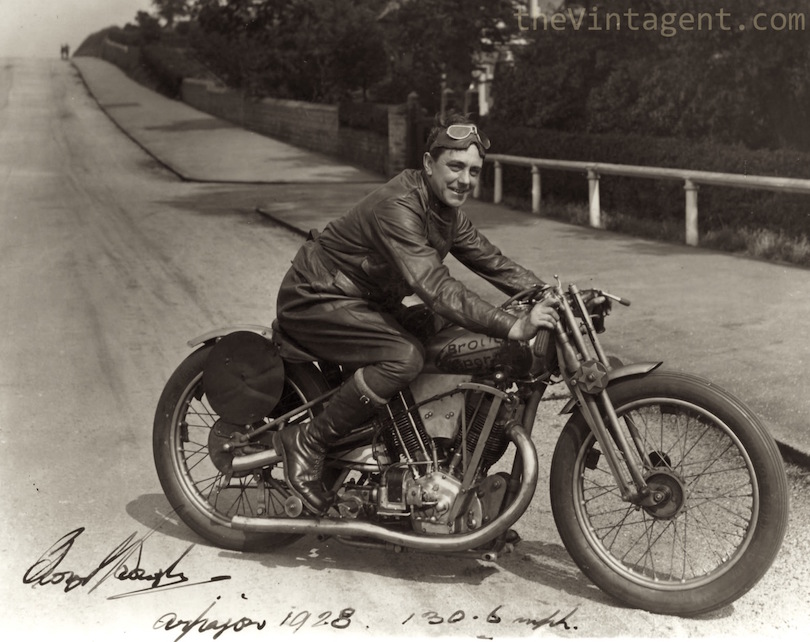

George Brough could not bear it - who the hell was Freddie Barnes anyway? – and hired LeVack to breathe a little harder on the 996cc KTOR JAP (conflict of interest? Good business for JAP!) and heated up the competition the next year, 1929, in Arpajon. George Brough himself rode his factory special to 130mph, the ride of his life, but failed to make a return run due to a minor mechanical problem. LeVack had better luck, averaging 207.33kph. That was the last time a normally carbureted motorcycle took the World Land Speed Record, as the big old V-twin engines had could not breathe any harder, and so were forced; the Age of Superchargers had begun.

The English builders Zenith, Brough Superior, and OEC all used the same big V-twin JAP engine, and OEC decided to trump their fellow countrymen by attaching a huge blower to their engine, which increased power by 20%, although the science of supercharging was still young; every plumbing modification and carburetion change was an experiment. Still, OEC hauled their new machine, along with fearless racer Joe Wright, to France; Wright piloted the OEC-Temple-JAP to 220.59kph (137.58mph) at Arpajon, a huge leap in speed, which meant everyone else needed a supercharger to play the Speed Record game. Wright’s run was also the first time a rider had officially exceeded Glenn Curtiss’ 1907 speed record…

== THE WAKE-UP CALL ==

While these three Kings of tiny, dirty, and unheated little English workshops – Brough, Barnes, and Temple – were having a splendid time in their private fight for ‘fastest’ bragging rights (on French soil), they didn’t hear the whine of a supercharged flat-twin blasting along at 221.54kph in Inholstadt, and knocking the British flag over. The English had mistakenly believed their own press and advertising, thinking their dominance of road racing and speed records was almost a natural right, a benefit of their extensive Empire and upper-class privilege, but they weren’t the only ones interested in going fast, and certainly weren’t the only engineers capable of building a really fast motor.

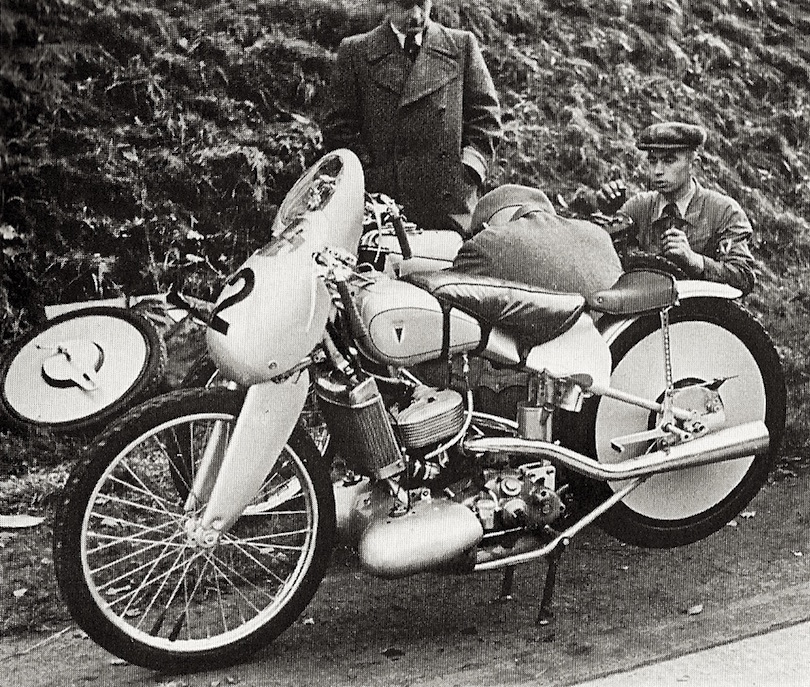

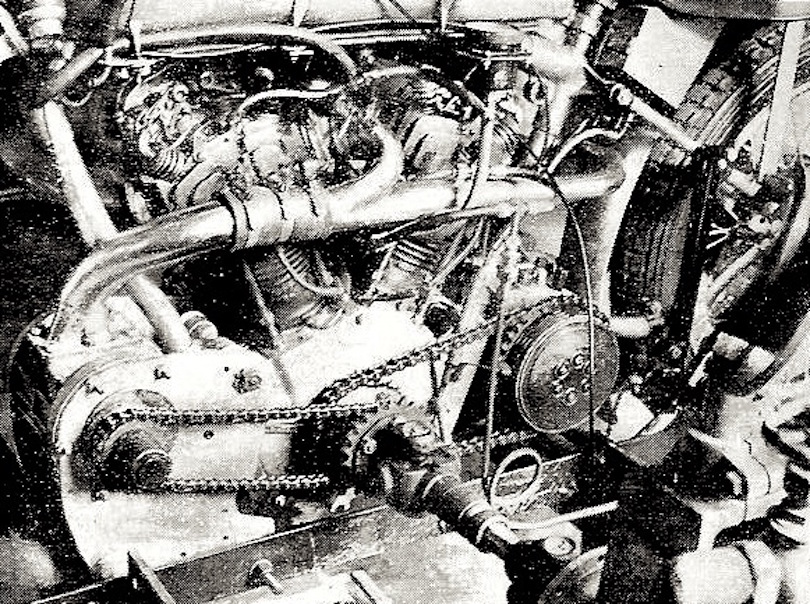

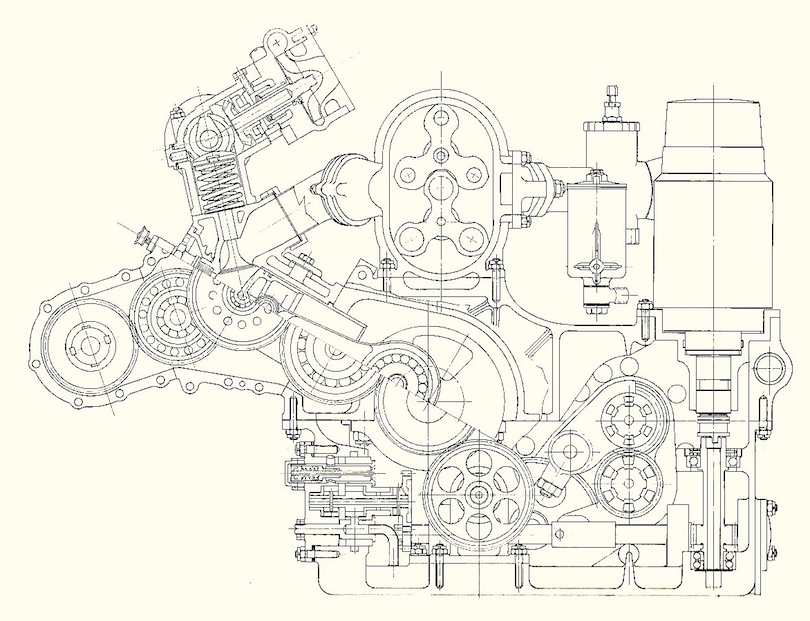

The Absolute World Motorcycle Speed Record, of course, was only one of dozens of speed records available, each based on combinations of time, distance, and engine capacity. Two German factories – BMW and DKW – were busy developing supercharged road-racing motorcycles; BMW since 1927 with a blown OHV 750cc flat twin, DKW since 1925 with their 175cc and 250cc two-strokes, which used ‘extra’ pistons to pump a fuel charge into their crankcases. Like manufacturers everywhere, BMW and DKW wanted to showcase their engineering prowess through racing and record-breaking, a process which accelerated rapidly in the 1930s, as DKW became the largest motorcycle manufacturer in the world with its simple but elegant two-stroke roadsters, and fiercely fast supercharged two-stroke racers.

International road racing and record-breaking heated up dramatically in the 1930s, regardless of the economic depression which gripped the industrial world. While English factories like Norton and Velocette developed straightforward and very effective single-cylinder overhead-camshaft racers (the International and KTT, respectively), engineers everywhere understood that an engine which moves air most efficiently, and spins at the fastest rpm, is the engine which produces the most power. Translated into metal, this meant more cylinders, supercharging, and camshafts near the valves for effective management of cylinder airflow. The science of the internal combustion engine had been laid down by English engineers like Sir Harry Ricardo and Harry Weslake, who published their principles for everyone to read, but it seemed the German and Italian translations were the best-thumbed.

Just because the facts are water-clear, doesn’t mean the horse will drink. For whatever reasons, cultural or financial, the English motorcycle industry failed to embrace the challenge presented to them in 1930s international motorcycle sport, and carried on with designs penned in the mid-1920s, right through the death of British GP racing in the 1950s. The biggest English factories – BSA and Triumph – had no factory race teams by 1930, while the biggest German and Italian factories probably spent TOO much money on racing. The British factories who did race (Norton, Velocette, Rudge, New Imperial, etc) had the best engine tuners and chassis designers, with decades of hard experience, who could extract more power and better handling from their reliable single or two-cylinder racers.

== The Scientific Racer ==

The writing was on the wall, and engineers from overseas approached racing motorcycle design from an entirely different perspective, science-based machines designed from first principles, with calculated power outputs and target speeds far beyond what any single-cylinder or V-twin motorcycle could reach. It was only a matter of time before their experiments were successful. The shock of a BMW taking the absolute World Speed Record was a matter of personal, and for the first time, national pride for the English competitors. BMW had only existed as a motorcycle company for 7 years, and was already at the forefront of supercharging technology, having bolted blowers onto their flat twins since 1927. While their supercharged road racers were fast, they didn't handle that well at the limits, and were no match on any race track with curves against the all-around riding excellence of a Sunbeam TT90 or Norton CS1 or Saroléa Monotube.

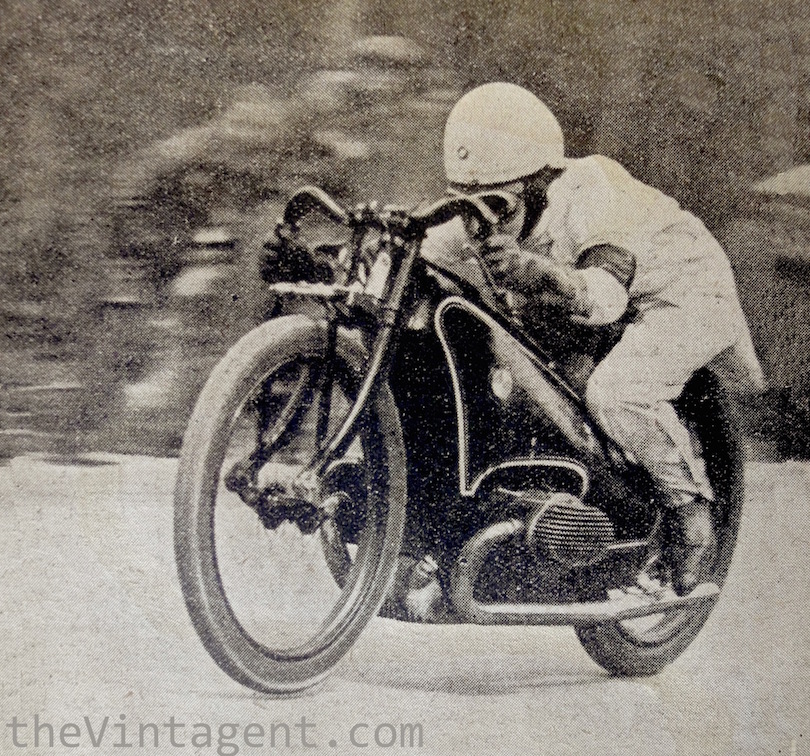

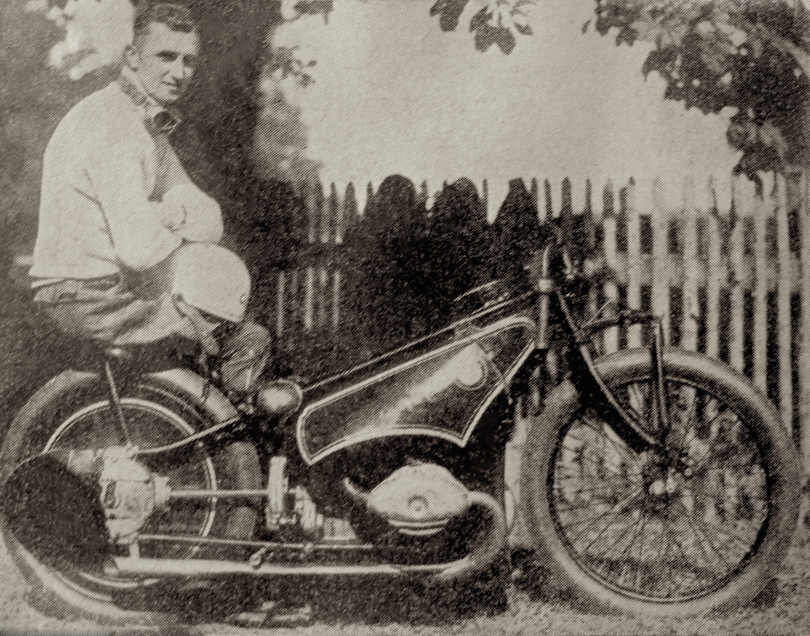

The WR750 Henne rode at Ingolstadt to 221.54kph was based on the R63 750cc OHV roadster, using the same tube-frame chassis, with some very special magnesium racing parts. It was partially streamlined, but only to the extent of covering the steering head and some of the bodywork in form-fitting sheet metal. While the overall effect was a bit lumpy, the WR750 was visually a more integrated motorcycle than its cobbled-up competition, because the entire machine was designed inside a single factory, with a set of engineers working to improve their product.

By contrast, their English competition formed an old-fashioned men's club of jolly sporting gents, who assembled the best components they could buy from industry friends, then worked with racing pals to combine these parts into the fastest possible package, in rented workshops beside the Brooklands track. The cross-Channel competition for World's Fastest became a battle pitting the Engineers against the Enthusiasts, the professionals against the privateers, the mind versus the heart. Of course, this metaphorical division is illusive; every effort required some mix of inspiration and experiment, but the flavor (or national character?) of our competing teams was distinct. Teams of engineers in Germany working from plans, versus teams of English speed addicts working from intuition and hard-won racing experience. The contrast between these factions became even more stark as the 1930s progressed, as the World Speed Record became a battleground between BMW and Brough Superior-JAP, and the political/propoganda implications of this proxy battle between rival nations grew far more serious.

Last of the old-school World Speed Record contenders: 'Super Kim', the 1925 Zenith-JAP modified in Argentina with a supercharger and 1700cc motor, seen here at the Vintage-Revival Montlhéry in 2011. A machine I found in Argentina many years ago, and which now lives in Germany.

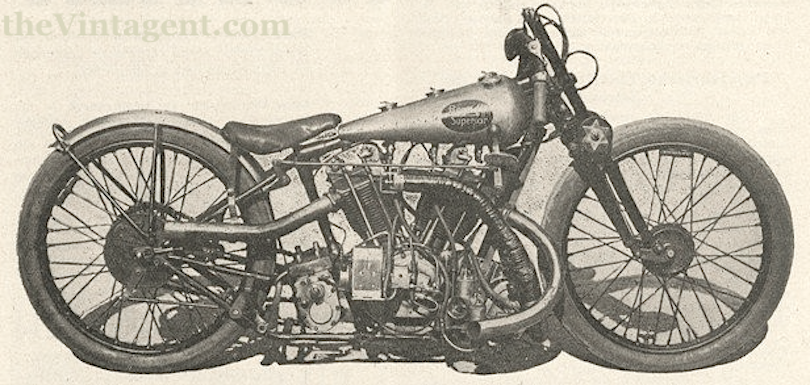

Stanley Woods and ‘Patricia’

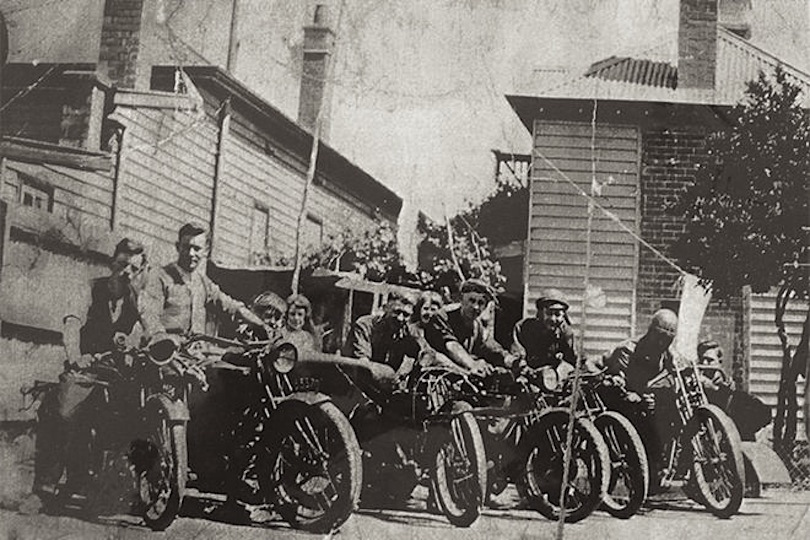

Stanley Woods was a rising star in motorcycle racing by 1923, having most notably won the Isle of Man Junior TT that year on a Cotton-Blackburne 350cc. At the end of the racing year, with a bit of prize money in his pocket, he decided to buy a big V-twin for daily use, hopefully a machine with enough sporting potential to race in the Unlimited classes at the Isle of Man and various beach events. So he went shopping at the big Olympia show in London, where all the manufacturers displayed next years' models. Woods explained, "I actually went to the motorcycle show at Olympia in 1923 with the idea of purchasing a Brough Superior SS80. This appeared to me, on paper, to be the most suitable motorcycle maker fitting the big JAP engine. However, I was looking for a discount off the machine. I had just won the Junior TT and had a big head. George Brough was not interested."

"I ferreted around the rest of the show, and looked at Coventry Eagle and Zenith. I finally set my eye on a New Imperial. Norman Downs, founder and managing director of New Imperial Motors, was a very keen supporter of the TT. When I approached him he was prepared to co-operate on hundred percent. 'Go and see the JAP people, the gearbox, the carburetor, the magneto people, and whatever they will do for you, we will do the same.' I got a machine at about 40% off instead of the normal trade 20%. It turned out to be a fabulous machine."

Woods raced his New Imperial in local road races (the Temple and Cookstown Hundreds), but found it was too fast for small tracks, although he did find success in sand racing and sprints in Ireland. The next year, having won virtually all the important Irish road races (but not the TT) he tried to convince George Brough once again to sell him the new overhead-valve SS100 model at a discount. George said no!

[ Note: these photographs were scanned from Stanley Woods' personal photo albums, which were sold at Bonhams auctions several years ago. The quotes from Woods are found in 'Stanley Woods: the World's First Motorcycle Superstar' (Crawford), to which I contributed a few photos.]

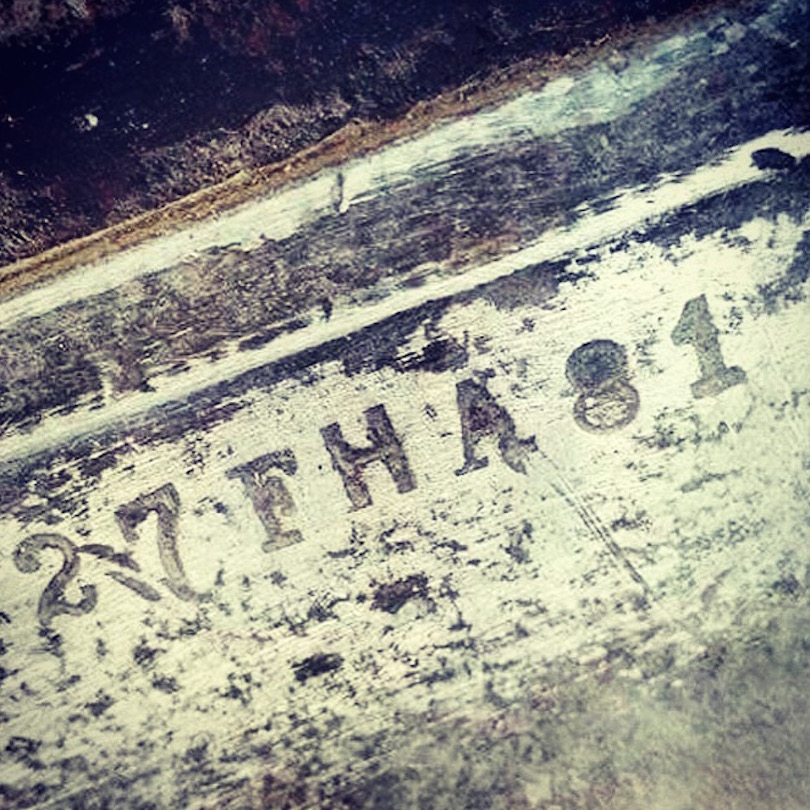

Harley-Davidson FHA 8-Valve Racer

It happens every year; an ultra-rare motorcycle is loosed from the cold, dead hands of a collector, and the 'Net is abuzz with the certainty that THIS, finally, is the Million Dollar Baby. Some odd mix of voyeurism and knowier-than-thou-ness compels us to excitedly proclaim the staggering rise in blue chip bike prices, while making a show of decrying the very same thing. The truth is, very few people are savvy enough to know what a blue chip bike is, and fewer still combine that knowledge with a willingness to take a risk and open their wallet. Prices have risen since the 1950s or the '80s or the 2000s, but the story remains the same - the folks who know and care and want important machines find where they're hiding and buy them. The folks actually shelling out the big bucks today aren't complaining, because they've known for decades that ultra rare motorcycles are undervalued. [For a little comparison shopping, check out my list of the World's Most Expensive Motorcycles]

The latest gem making the rounds of Instagram (and TheVintagent!) is this just unearthed, single-family for 50 years Harley-Davidson FHA 8-valve racer, which is documented and in as-last-raced condition. Huzzah; a no-bull 1920s Class A racer which doesn't appear to have been messed with or faked up, like nearly all the others of its ilk. Hilariously, some of the folks who've sold less than perfect American racers in the past few years have shown their hands with this machine, praising its originality and the importance thereof, while no such praise was possible for their own bikes! But that's the reality of most old racers - they're usually compromised in the very areas collectors prize most; matching #s, original sheet metal, clear provenance. When presented with a machine with all boxes ticked, the temperature rises.

This FHA is among the last of the factory 8-valves produced by Harley-Davidson, as they were already experimenting with more reliable ways of producing power, and more, the American Class A race series was about to vanish due to the Depression, in favor of Class C, which was production-based and therefore much cheaper for everyone, favoring 'mundane' sidevalve engines instead of 'exotic' OHVs. Of course, factories across the pond had been producing fast and reliable OHV bikes in increasing numbers since the 'Teens for everyday use, but American buyers trusted valves on the side, but that's another story.

The FHA used a twin-camshaft timing chest, externally distinguished by the raised ring on the timing cover, which of course meant better valve control and thus higher revs and more power. The revs were also made possible by the good airflow of the 4-valve cylinder heads, which took advantage of the gas-flow research of Sir Harry Ricardo, which proved many small valves pass more air than two big ones. But without positive lubrication and the oil cooling it provides, a grease-lubed 4-valve cylinder head is a fragile thing, even with the rocker gear exposed to the airflow... plus dirt, cinders, and dust when raced on the Australian tracks this beast has seen.

[Update: the FHA sold for A$600k, which was $423,700US on the day, making it the #10 most expensive motorcycle ever sold at auction]

Favored by the Gods of Speed

Over the past few years, Bonneville seems determined to reclaim its lakehood, to the great disappointment of speed fans who’ve traveled the globe to test their metal against the clock. The Speed Trials have been cancelled several times, so last weekend the SCTA - hallowed sanctioning body of speed - held its first ‘Mojave Mile’ event at the Mojave Air and Space Port airstrip, to allow all those revved-up teams a chance to redeem their substantial investments. The Mile is different from Dry Lake top speed runs, organized more like a solo drag race over the 12,500’ runway used by the Space Shuttle. There’s another ‘Mojave Mile’ event which is open to all comers, but this SCTA event was only for Land Speed Record machines which fit the appropriate specs/regulations, and fills the gap left by a wet early-August Bonneville. With no spare real estate for a typical speed run, riders are WFO from the start line, with their speed measured at the end of the run.

Among the Mojave competitors was Bonneville regular Alp Sungurtekin, an Industrial Designer who has developed a pair of pre-unit Triumph twins into the most potent examples ever built for speed. I met Alp at end of the 2013 Bonneville Speed Trials, where he agreed to sit for a few ‘wet plate’ portraits. His first machine, based on a 1950 iron-head Triumph 6T Thunderbird, is legendary for recording 132mph at Bonneville, with a two way average of 127.092mph, making it the world’s fastest unfaired 650cc stock-framed Triumph in the Vintage gas class.

With the experience gained from his success, Alp built a totally new bike in 2014. “I’ve been designing this Special Construction-class bike for 2 years, thinking it over and drawing it out on the computer, and started building it in November 2013. The frame and all components were finished in March 2014 - it took 4 months to build, and was ready for the May races. My first test that May was bolting the 1950 engine into my new frame, and the bike went 139.226mph, the A-VG record, and that June it recorded 140.2mph.”

As seen in these photos, Alp’s new racing frame is built to keep the rider as low and close to the engine as possible. As a result, it’s a tiny machine, with the engine sat well back, and a very short final chain run. The engine plates were built of ½” thick 6061 aluminum alloy, which were hand cut, as Alp has no milling machine. The engine and gearbox form a structural part of the frame with their substantial engine plates.

“I have a nice 1958 Buffalo Forge Drill Press that I used like a mill to smooth out the edges. Took forever, little by little. I always fabricate my prototypes by hand and test them on the race course, but all the parts that I build for my clients are CNC or waterjet cut. The frame is very accommodating; its designed to ‘complete’ the rider’s body. It’s not just about the right weight or geometry, it gives a really good weight ratio distribution for maximum traction. Another feature of the frame is adjustable axle plates that make it possible to change the ground clearance and wheelbase. It’s different ergonomically, the difference between a land speed racer and a drag bike. The sitting position won’t let you take off instantly.”

Alp’s Vintage-class iron-head 1950 Triumph Thunderbird uses the original Triumph engine cases, barrels, and that single-carb iron cylinder head, and runs on gasoline. After recording 132mph with that motor, he began work on a new engine with an all-alloy top end and twin carbs, to compete in the Special Construction “A” class. The twin-carb alloy head is post-1956 (it's a '64 head), so is ineligible for the Vintage class, but runs in the 650 A-PG/F class. Aftermarket cases are allowed in this class, and Alp is sponsored by Thunder Engineering, who supplied beefed-up cases and rods. The engine was designed to run on Nitromethane, which gives tremendous power - a supercharger in liquid form - but is known to reveal any lubrication or heat dissipation issues in a spectacular fashion. “The Nitro gave me clutch problems initially, but the good thing is I didn’t blow up the engine. My Vintage Triumph, running on gasoline, puts out 58-60hp and will hit 140+mph. But many tell me with the Nitro, my later engine probably produces more than 140hp at 160+mph.”

“I first tried the new all-alloy engine in the 1950 frame; running on Nitromethane we hit 149.279mph. That’s with a stock Triumph frame! But I didn’t realize that I’d bent the frame, and the rear fender mount shredded the rear tire and slowed me down – I was on my way to 160mph. The existing record was set in 1995 by the Tatro Machine Special Harley-Davidson – Many fellow SCTA racers told me he blew up many engines to get that speed. He heard that I’d broken his record, and is coming back in October!”

“With the alloy engine in the new frame, I was recorded at Mojave doing 169.1mph -within a standing-start mile, with an exit speed of 172mph. As you know, we’re running a pre-unit 650cc open-class motorcycle with no fairing! This is a speed no other naked vintage or pushrod 650cc motorcycle has ever achieved in the history of Land Speed Racing. Our speed is faster than the 650cc/750cc partial streamline APS-PG/F bikes and 750cc / 1000cc open pushrod ‘fuel’ bikes as recorded by any sanctioning body – SCTA/AMA/ECTA.”

“The success of a racing bike is the whole package, not the parts. I designed my frame for this engine, and I balanced the engine and crankshaft for this frame. Howard Allen, who used to race at Bonneville and El Mirage in the 60’s/ 70’s with Triumphs and Harleys is one of my greatest inspirations, he was always there when I needed help. For speed, my cylinder head is the key. Doug Robinson, builder of the BMRRoadster (the world’s fastest naturally aspirated roadster at 290mph) told me the only secret to speed is how you get the air in and out of the cylinder head – it’s a pump. I’ve probably redesigned and built between 15-20 heads in the past few years; how I modify them is probably my only tuning secret. I’m using NOS cast pistons (which I wouldn’t recommend), buying them oversized and shaping them by hand – they look really funky and organic.”

Alp would like to thank his sponsors: Lowbrow Customs (Amal GPs), Klotz Synthetic Lubricants, Morris Magnetos, Thunder Engineering (cases and rods).

Out of the Blue, Into the Black

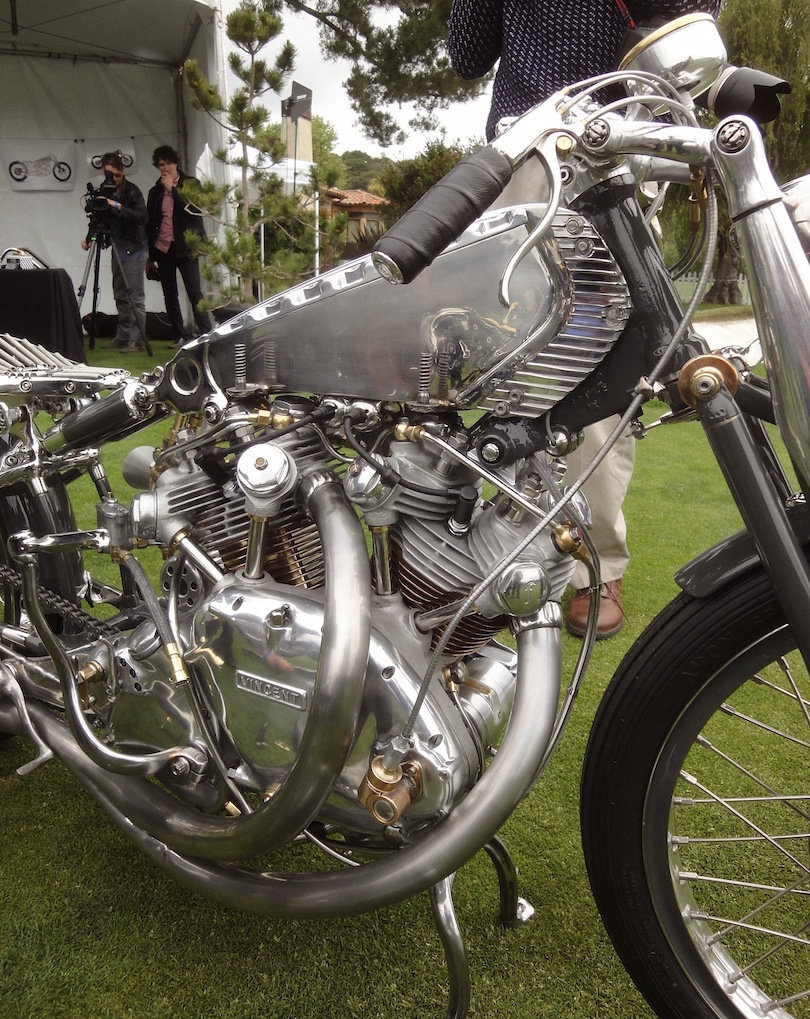

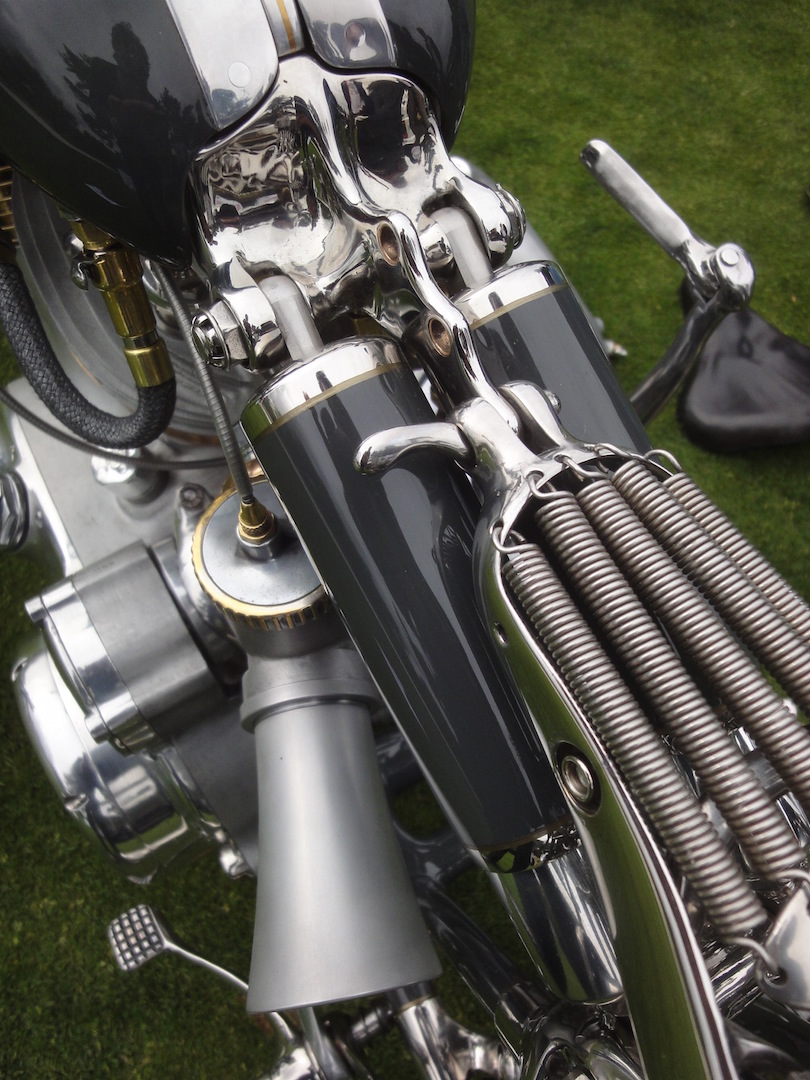

Vincent Black Shadow. Legend, faded photograph, dog-eared book, campfire ghost story, popular song. A dark castle formidable with reputation, built up over the decades as owners, and those who aspired to own, called her ‘widow maker’…‘the world’s fastest standard motorcycle’… ‘pure hell on the straightaway’...’snarling beast’.

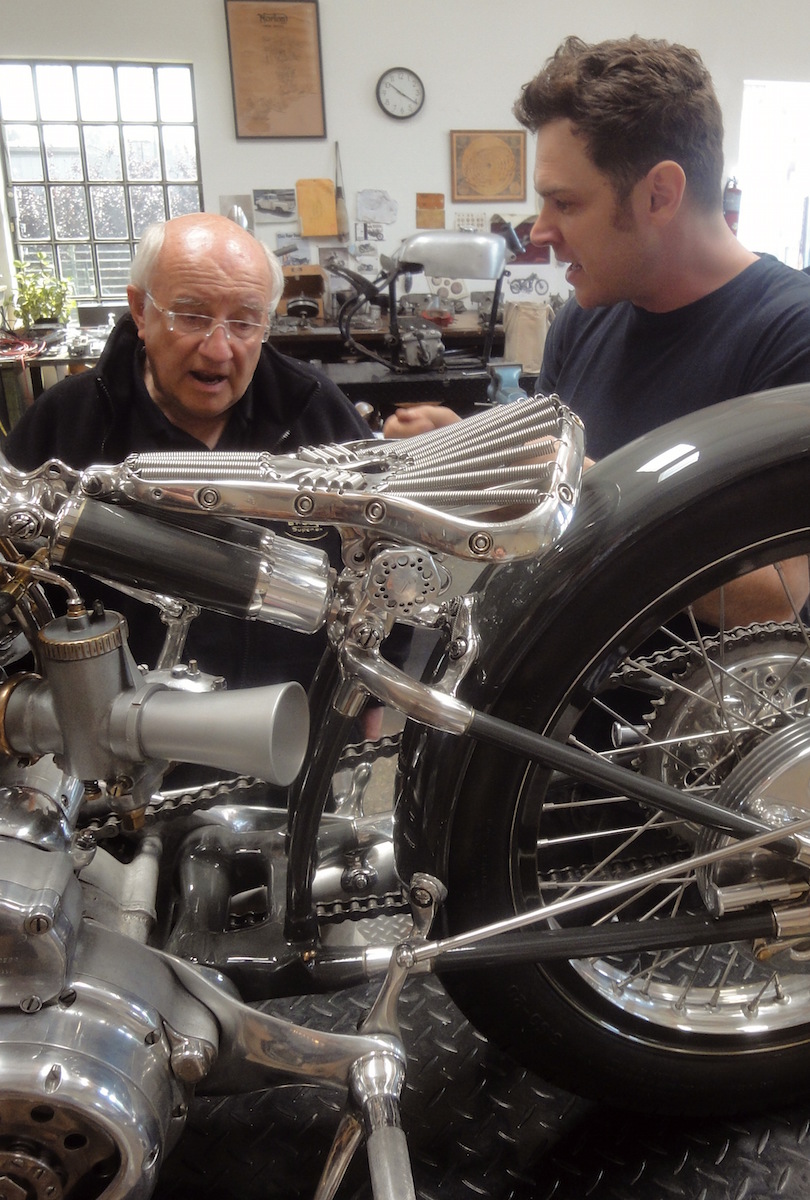

To approach a Vincent Black Shadow, intent to improve it, while standing in the spotlight of peer and media scrutiny, is an act of folly, egotism, or sheer screw-you audacity; examples of each have Been Done in the Custom world. You may celebrate or denigrate these altered Vincents, but they exist as a confirmation of the Black Shadow’s stature in the motorcycle Pantheon. Something which had Not Yet been done, though, is wrestling with the ghosts inside the Shadow (‘the Phils’ Irving and Vincent), embracing them with one’s thoughts, hands, and tools, finding new solutions to their old problems, re-thinking the whole motorcycle, re-solving their original questions. Rare humans have strength of character, and lack of ego, to work with the legendary deceased as trusted advisers, but Ian Barry, for example, is such a man.

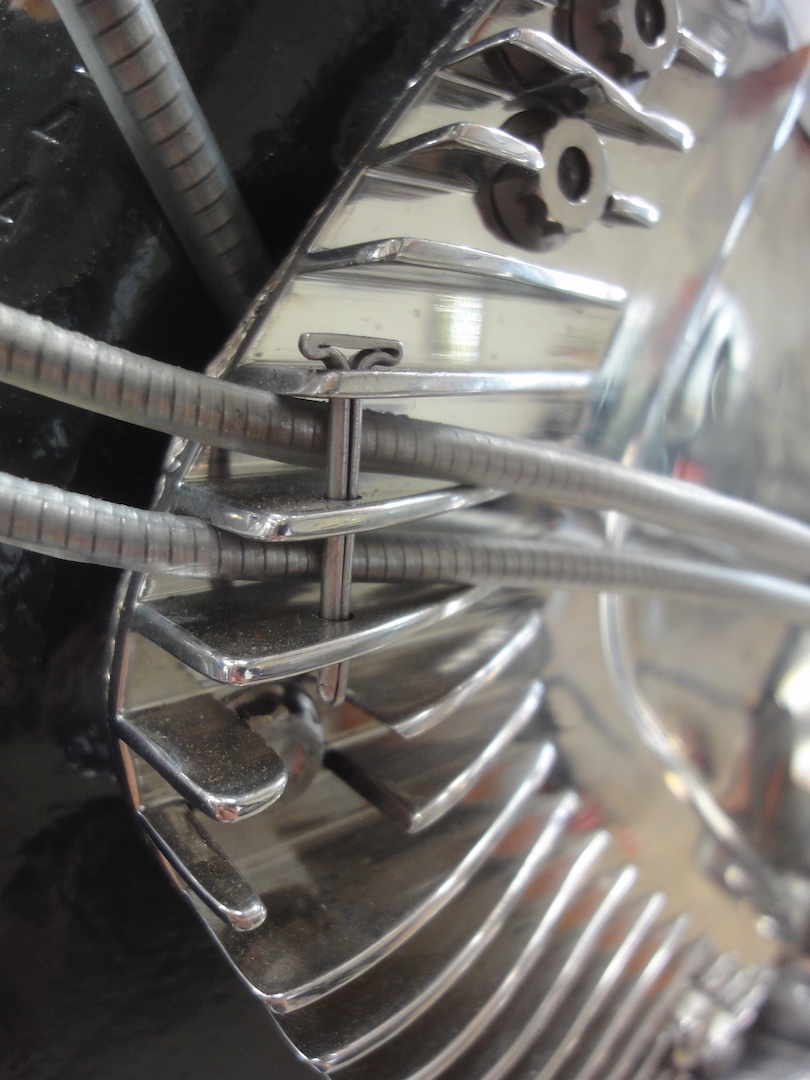

That the Black is both a Falcon and a Vincent simultaneously, is testament to this collaboration’s success. The Australian engineer Phil Irving, the v-twin’s mechanical designer, was notorious for quirky ‘solutions to problems nobody asked’, creating rider adjustability - without tools - for brakes, chain tension, riding position, even gearing. Barry has taken Irving at his word, examined these ‘conveniences’, and made them more elegant, more beautiful, and in fact, more functional. The front and rear wheels, seat covers, and even the petrol tanks can be removed with no tools at all, while the handlebar and footrests position, chain tension and brake adjustment are all easily fine-tuned by hand, very much in the spirit of the original Vincent, but better.

Phil Vincent was an uncompromising visionary, who acquired the ‘HRD’ motorcycle name from bankrupt TT-star Howard R. Davies in 1928, hoping an existing brand name would give a head-start to his advanced ideas on chassis design. The early HRD-Vincents used stiffened, strutted frames for good handling, plus a distinctive triangulated swinging-arm suspension which Mr. Vincent patented in ‘28, which looks like a modern ‘monoshock’, but in fact originally used a pair of springs with friction dampers for shock absorption. These early, awkward-looking HRD-Vincents were single-cylinder machines, but by 1936, with Phil Irving’s help, a 1,000cc v-twin engine was created, the inspiration legendarily arriving when two tracings of the single-cylinder engine were overlapped. The Series ‘A’ Rapide had arrived, and it was the fastest production motorcycle in the world, capable of 185kph.

During off-hours in WW2, ‘the Phils’ discussed and drew up plans for a much-improved v-twin, which débuted in 1946 as the ‘Series B’ Rapide. Eliminating the unnecessary weight of a tube frame, the ‘B’ used the new unit-construction aluminum engine as a stressed element between Brampton girder forks, and that distinctive triangular swingarm, which now used hydraulic shock absorbers. The new Rapide was faster, more robust, and a much cleaner design than the pre-war ‘A’, giving 190kph performance, if you had a good one. As the Vincent factory was not destroyed by German bombs in WW2, the machine tools which built the new Rapide were old and worn, giving rise to inaccuracy in machined parts, so laborious hand-assembly was required to bring out the best in the engine. When the new ‘Black Shadow’ super-sports model was announced in 1948, the 200+kph top speed was created less by ‘hot’ new parts, than the careful selection of the timing and valve gear, properly-machined castings, and ‘blueprinted’ assembly. In truth, ‘good’ Rapides could be every bit as fast as Shadows, but lacked that magic name and sexy all-black paint finish. Still, the series ‘C’ Black Shadow, now with radical aluminum ‘Girdraulic’ front forks, retained the ‘fastest in the world’ title for Vincents, reaching a peak with Rollie Free’s immortal ‘bathing suit’ run at the Bonneville Salt Flats on a Shadow at just over 150mph.

Thus the legend of the Black Shadow was created, and continued to grow long after the Vincent factory stopped producing motorcycles in 1955. The image of Rollie Free stretched out and nearly naked at 150mph, the Hunter S. Thompson articles and books making crazy claims for lethal Vincent performance, and Richard Thompson’s song ‘1952 Vincent Black Lightning’, piled rumor onto story onto myth.

After all that hype, the Vincent in the final analysis is just a motorcycle, but a damned good one for its day. But of course, 1940s technology leaves plenty of room for improvement, and the Vincent twins have always attracted Real Riders, who modify their machines as they see fit for touring, racing, or posing. But nobody has modified a Vincent Black Shadow quite like Falcon.

The list of work done on the Black is staggering, but to sum up, the chassis was completely fabricated by Falcon, barring a single humble lug, at their LA warehouse; frame, forks, brakes, tanks, handlebars, controls, seat, mudguards. Their silhouette is familiar as Vincent, clearly a family member, but everything is changed. The forks are brand new and modernized, yet still Girdraulics; the blades completely redesigned with weight carved away, all bearings changed to needle-rollers for free movement, and the shocks are modern gas units, made bespoke by Works Performance to Falcon spec. The front brakes have 4 leading shoes, their backplates rigid against the forks, with twin drums spoked shorter/stiffer than the originals, with double the braking power, and lighter to boot.

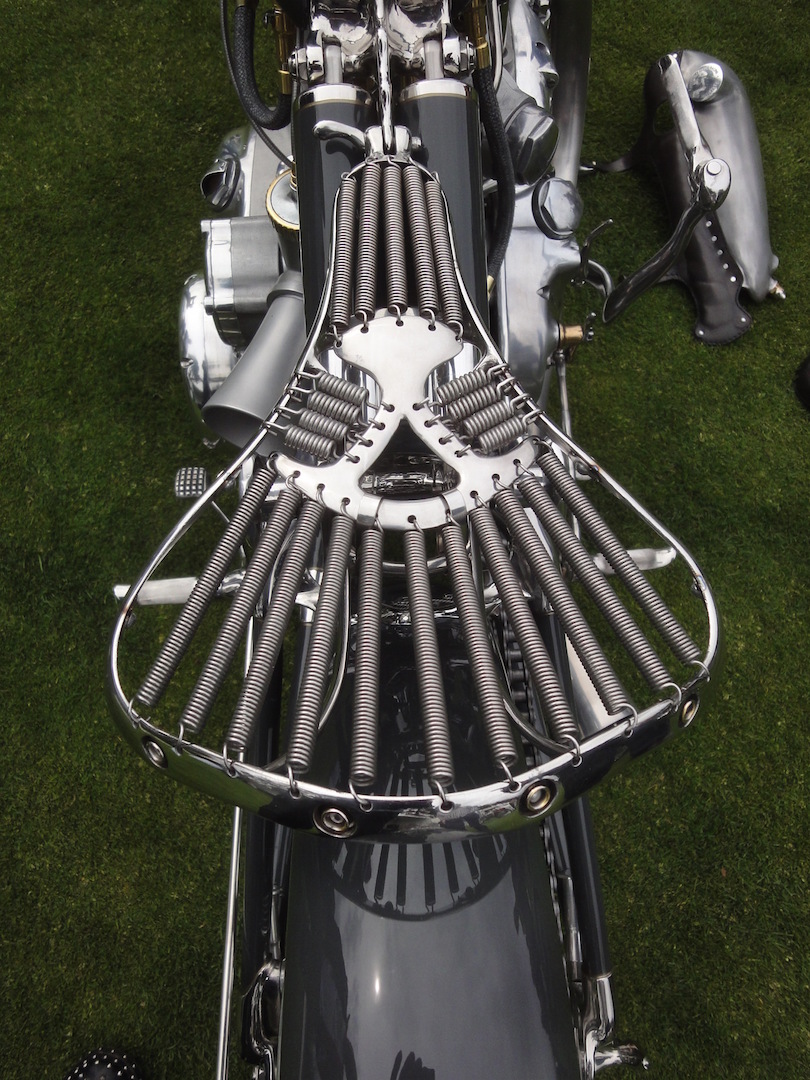

Phil Vincent’s triangulated rear end has been lengthened with a more robust pivot area, and the suspension modernized with another pair of Works gas shocks. The seat, perhaps the least satisfactory element on a Vincent, is replaced by a small saddle, very light, cleverly constructed, and far racier than the ‘King and Queen’ before. The structure of the saddle, with the leather cover removed (another by-hand job, to swap ‘touring’ or ‘racing’ covers), is a fascinating and unique design by itself, and on any other machine it would shout. Peer under that seat at its mount, and say hello to a beautiful sculpture, put to new employment.

The oil talk, being half the frame of a Vincent, was fabricated entirely of stainless steel; now cooling fins act in symbiosis with pannier fuel tanks, whose hollows guide onrushing air towards the cylinder heads and bronze-alloy barrels. Those hand-formed aluminum tanks press-and-click onto damned clever spring-loaded pins, vibration-damped by rubber o-rings. With push-fit marine fuel taps, the entire system is removable in under 30 seconds, with no tools, if one needs to switch from ‘touring’ to ‘sprint’ mode, using the single small pannier tank with leather straps.

While the Amal GP racing carburetors thrust dramatically outwards at odd angles, this was standard Vincent dry-lakes racing and sprinting practice in the 1960s, which is the legacy of this particular Black Shadow, which lay in boxes for nearly 30 years in San Francisco. The radical air intake blows back out through a gracefully curved 2-into-1 exhaust system; the carbs and pipes are the most visually extravagant features of the Black, as the whole machine is characterized by remarkable restraint. There are no fancy flourishes or flashy paint jobs, no engine-turned decoration, no engraved scrollwork, no gemstones or precious metals.

The staggering volume of Time invested to create the Black – 7 highly skilled artisans spent an entire year of their lives building it – was not spent ‘decorating’ a custom Vincent. The time was spent creating new engineering solutions to the same set of problems faced by ‘the Phils’ when originally designing the Black Shadow, and once these new solutions were devised, each part was crafted in metal as an object of striking beauty in itself. That Falcon’s parts are superior in their function to the original Vincent parts is outrageous, a slap in the face of History, and generates questions not typically raised in the world of Customs, where Form generally follows Fashion. Questions like, ‘when is a design finished?’ and ‘can an iconic motorcycle be a conversation over time?’ and ‘just who does Ian Barry think he is?’

This is the Falcon signature -Ian Barry’s metal handwriting - the sheer sculptural beauty of the motorcycle and its parts, combined with extremely functional modifications. In this, Barry and the Falcon team are in very rare company, and their work is pushing the boundaries between motorcycles, fine art, and jewelry. The Black is #3 of Falcon’s projected ‘Concept 10’, and exhibits the definitive stroke of a young designer gaining confidence and technical prowess, unafraid within the swaggering world of Motorcyclists to shape footrest hangars, tommy bars, air scoops, and even frame lugs in the most gorgeous, bone-like, and organic forms, shapes impossible to machine, proud evidence of their hand-made creation. Cast them in silver and sell them to fashion houses, the bits are drop-dead gorgeous. Bolt them together, and we have an Olympiad with the figure of Jessica Rabbit. Some lucky bastard actually owns this motorcycle…but he can’t stop us filling our eyeballs.

Ian Barry at Kohn Gallery - The New York Times

|

| [the White installed in the Michael Kohn gallery in Los Angeles] |

|

| The Black. photo: Ian Barry |

|

| The Kestrel. photo: Ian Barry |

|

| The Bullet. photo: Ian Barry |

Jeff Decker's 'Black Lightning' at Auction

'The Ride' Hits the Bookshops

Apologies for being near-absent a few weeks on TheVintagent, but I've been finishing my contribution to the BikeExif book, 'The Ride: New Custom Motorcycles and their Builders', published by Gestalten in Berlin, which I co-wrote with Chris Hunter, David Edwards (Bike Craft, Cycle World), and Gary Inman (Sideburn). Gestalten publishes big, beautiful art books; this is their first motorcycle book, but as 'The Ride' is already #1 on Amazon's 'motorcycle' search results, they'll likely publish another! I met with Robert Klanten (publisher at Gestalten), in both Biarritz (for Wheels and Waves) and in his offices in Berlin; as a lifelong rider, he's the perfect guy to pursue the subject.

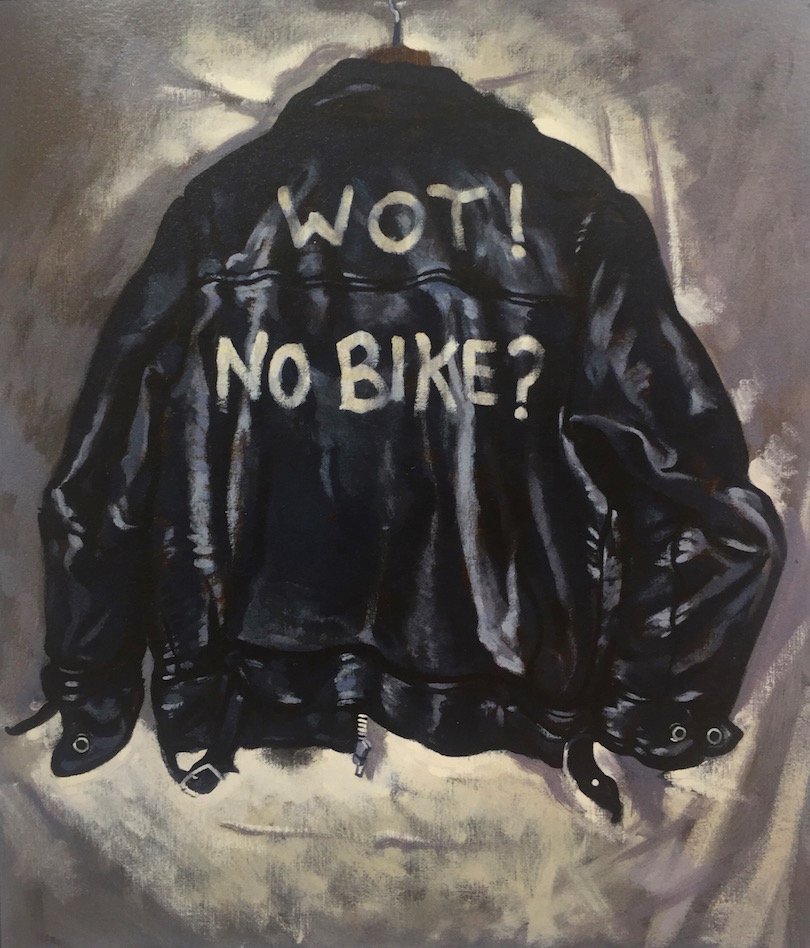

Wot! No Bike?

Guest post by David Lancaster.

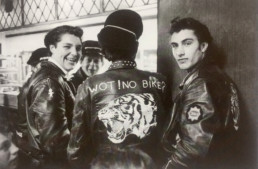

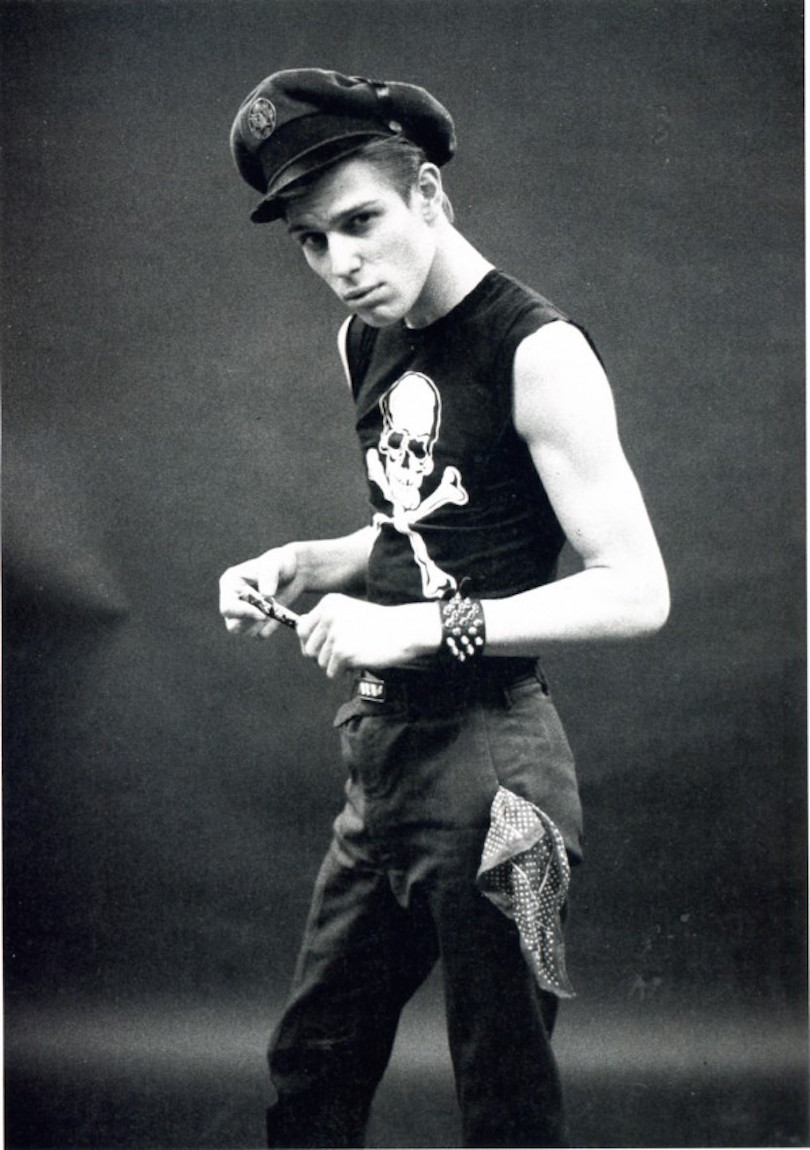

Paul Simonon’s first memory of motorcyclists is etched in his mind. “It was in Paddington, where I grew up,” he recalls. “Rockers would hang around the 59 Club there, tearing up and down on bikes. One time, a bunch of these characters started wolf-whistling my mum. I said: ‘Who are they?’ – like she knew them. We kept walking. But something lodged. These things are very vivid when you’re a kid – these people racing around, the leathers like a suit of armour.”

Fast forward some years, and the former Clash bassist’s new series of paintings and book Wot No Bike distil a lifetime of painting and riding motorcycles, and the enduring appeal of the classic biking and punk rock uniform: the black leather jacket.

The Clash were perhaps the coolest and most enduring of punk bands. In addition to his bass playing and occasional song writing, Simonon’s artistic sense and drive also led the band’s distinctive look and stagecraft. Since the band disbanded in 1986 and frontman Joe Strummer passed away in 2002, Simonon has played with Damon Albarn’s groups Gorillaz and The Good, the Bad and the Queen.

But painting came before bass playing. As did motorcycling – a later brush with two-wheeled culture came when when a scholarship took him to Byam Shaw School of Art in central London. “There was girl there called Dianne. She was a short little girl, but she had this great big British bike,” he recalls. His head was turned onto British bikes.

The Paddington of Paul Simonon’s childhood, his home just minutes from the 59 Club, still bore the scars of its semi-industrial past. A nexus of road, rail and canal trades meant the area’s streets were a potent brew of workshops and pubs servicing the rail and canal industries. In many ways it was still the Paddington captured by one of his favourite artists, Algernon Newton, dubbed the ‘Canaletto of the Canals’ after his 1930 view of The Regent’s Canal, Paddington. Newton’s work, according to critic Richard Dorment, captured “vast featureless brick blocks built during the industrial revolution that had by then fallen into a state of dereliction”. Even in the 1950s and 60s when Paul was growing up in west London this remained the case – splashes of colour, such as they were, were mainly the state-monopoly red of Routemaster buses and Giles Gilbert Scott’s robust telephone boxes.

The area – “holding on to its soul today, just” according to Paul – housed the 59 Club in the hall by St Mary’s Church. It was run with a benign zeal by Father Graham Hullett, a committed motorcyclist and man of the cloth who, according to regulars, “wore his faith lightly”. For Lenny Paterson, 59 Club regular who was later to reignite so much with his Rocker Reunion Runs of the early 80s, “the 59 Club in its Paddington heyday was a magic time.” Not only did it offer a place for London’s young rockers to ride to, meet at, and fall in love in but in 1968 its private members’ status meant it was able to screen László Benedek’s The Wild One for the first time in the UK after the film was banned in the late 1950s.

The classic 1950s and 1960s rocker look of black jacket, straight-legged denims or leathers which had struck Paul in the late 1960s would re-emerge in punk of the mid-1970s, but not without a struggle. The greasers and teds of the 70s would cross the street to start a fight with a punk. As Joe Strummer observed in a late interview, punks took their uniform and “tore it up… which they saw as disrespecting their kit.”

Yet, despite fights on the King’s Road between teds and punks, the links of style and personnel between music and motorcycling had never been so close since the 1950s. As fellow punk pioneer and classic motorcyclist David Vanian of The Damned says, “Rock and roll of the 50s came and went really quickly, and didn’t get a chance to mature. The look was clean, sharp.” The links between the two struck legendary DJ John Peel too, seeing the “raw energy of early rock and roll” re-emerge in punk’s guitar-led attack compared to the stoner-indulgence of much 1970s music.

It was fellow musician, the late Nigel Dixon from rockabilly outfit Whirlwind, with whom a shared love of motorcycles – and chance – led the two to take up biking Stateside and a further chapter in Simonon’s two-wheeled and musical life. “After the break-up of The Clash, we spun a globe – to see it land on El Paso. So we sold our bikes in the UK, and went to live in El Paso, and bought these two old Harleys,” he recalls. After riding across from El Paso to LA, the two pitched up at a bar to be met by a girl Paul knew from London. “Paul, I can’t believe you’ve got a bike like Steve’s!” she said. And so ensued recording sessions with Bob Dylan and months riding around LA on old Harleys with Steve Jones from the Sex Pistols and others, “Like a long, leather motorcycle snake,” as Paul puts it.

But the major influence on Paul Simonon’s motorcycling was the author, eccentric and Russian art expert, Johnny Stuart, introduced to him by Dixon. “The first Triumph I had was a white and gold 3TA”, Paul recalls. “And then a 5TA off a mate of Johnny Stuart’s. We’d all hang out, go for runs. I got to know him very well.”

Stuart was a key figure in late 70s and 80s London classic motorcycling, and Paul’s life at the time. Not only did he pen the seminal Rockers! in 1987 which collated and chronicled the rockers’ movement (Paul is photographed in it) but he built up an archive of original jackets and a network of friends and riding buddies who crossed boundaries of class, work and background. Paul remembers a “complete one-off – a scholar, rocker, great host.” Appointed Sotheby’s expert in Russian icons in the 1970s (his rival at Christie’s dubbed him the “greatest authority on Russian art outside of Russia”) he passed away at the age of just 63. A jacket of Johnny’s features in Wot No Bike.

“Johnny loved every aspect of 50s and 60s motorcycling,” says Paul. “The look, the bikes, the sound. Like everything he did, he became an expert.” His lodgers, Crispin Ellis and Trudi Gartland, would park their bikes next to their ground-floor double bed after a run, and Stuart’s Colville Mews house was, until the very end of the illness which took his life in 2003, a heady mix of Russian icons, dismantled Triumph engines, rockers and musicians such as Siouxsie Sioux, Brian Setzer from the Stray Cats and, of course, Paul. “You’d come home and there’d be a few bikes outside,” Trudi recalls. “But also a black limo, surrounded by bodyguards, as Johnny was valuing a piece of Russian art for some high roller.”

There is a quiet determination about Paul Simonon. He’d been playing bass for just six months before The Clash’s first recording. Yet, just a few years later, the band cut London Calling, dubbed by Rolling Stone magazine the best album of the 1980s. Simonon’s reggae-infused bass is a key part of such epitaphs: on the album’s title track it is as distinctive as Herbie Flowers’ playing on Lou Reed’s Walk On The Wild Side, adding a muscular energy and attitude to the limited canon of bass-lines you can you hum, but which also make the record. “The only punk band with groove,” according to Scott Rowley.

His painting displays the same application. For an earlier series of London landspaces, part of the process was “just getting out there, on a bridge, in the wind and rain, and painting,” he says. “I’d avoid eating or drinking – you didn’t want to leave the stuff unattended, or pack it up for a break. So I just carried on, with the odd smoke, for hours.” These days, his Paddington studio is warmer but the same work ethic is evident as the visitor takes in several canvasses on the go. He likes to “keep painting through”. Such commitment extends to being imprisoned for two weeks after working on a Greenpeace ship as a chef, his background unknown to his fellow activist-inmates.

Wot No Bike captures much about classic motorcycling, in elegant still-life. The artist himself is an off-screen presence to a jacket on a chair, or gloves, cigarettes and crash hat resting after a run. “A leather jacket never ages,” he says. A jacket swapped with Joe Strummer for one of Paul’s earlier works – “he couldn’t believe I would paint washing up, in a sink… so we swapped” – carries the title of the book and exhibition.

The paintings are refreshingly traditional, in the realist tradition Paul admires. And in the dark creases, distress and crumpled leather it speaks volumes of two-wheeled experience, both good and bad. “Johnny Stuart used to urge me to ride in the rain more,” remembers Paul. “I couldn’t see the appeal much then. But now he’s no longer with us to tell, I really get it: the balance of power and traction. The focus.”

Simonon’s daily ride is a lightly modified Hinckley Triumph. “The funny thing is when my mum first saw me with my bike, she said: ‘Oh, that brings back memories – your dad used to have a bike like that, a Triumph.’ Then I found out he was a dispatch rider for the army, in Kenya. These things come out. And now one of my sons has a bike. At a young age, he would say to me: ‘Dad, I want to make something that can propel me somewhere.’ And I’d say: yeah, it’s called a motorcycle.”

………………..

Based on his Introduction to Wot No Bike © David Lancaster

Pictures © Dave Norvinbike as marked, and others

The exhibition runs at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London SW1 from January 21 until February 6 (www.ica.org.uk).

Copies of the accompanying book available from Amazon and signed copies from www.paulsimonon.com.

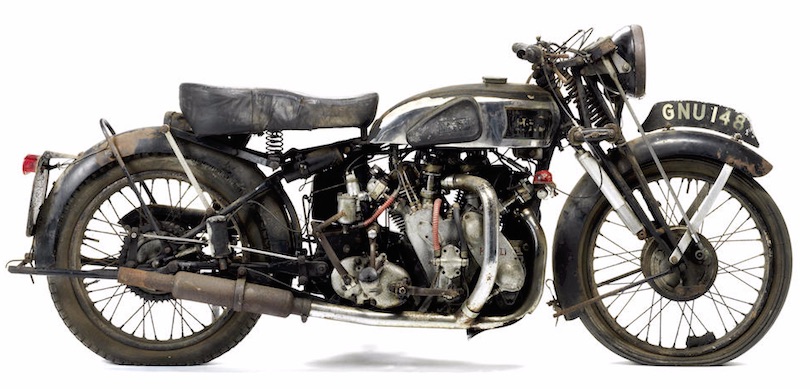

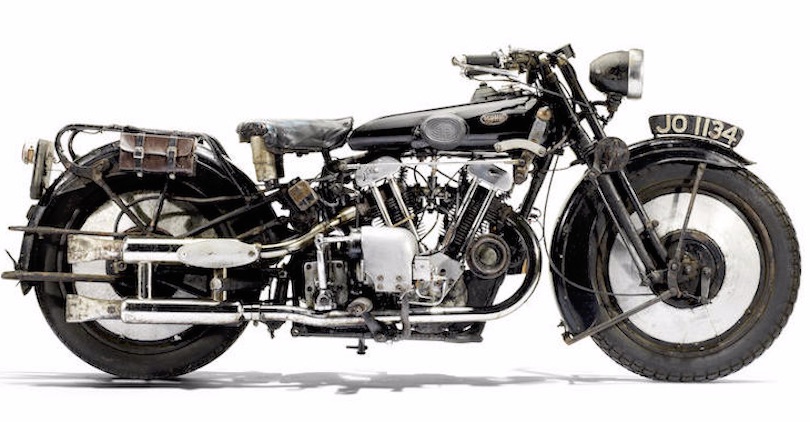

The Last Great Brough Hoard?

I've heard rumors of this collection for years; a fine hoard of Brough Superiors, including SS100s and a 1-of-8 Brough/Austin 3-wheeler, sitting outdoors in a south England yard, and slowly rotting away. The owner refused to consider many offers for individual machines or the whole pile, preferring to watch them slowly return to earth than watch grass grow in their stead.

The rumors were recently confirmed by Ben Walker, who had just secured the rights to sell the collection of the late Frank Vague of Cornwall. When he sent a 'for your eyes' photo of the machines in Vague's yard, I knew this was the collection so long spoken of. So true, and so very sad! But, as given the value of all Broughs, there's no doubt every one of them will be brought back to as-new condition in short order, keeping the likes of Dave Clark and other Brough restorers busy for many years to come!

Ben Walker says, “This is one of the greatest motorcycle discoveries of recent times. A lot of mystery surrounds these motorcycles, as very few people knew that they still existed, many believing them to be an urban myth. There was a theory that they still existed somewhere in the West Country, but few knew where. Stored in barns for more than 50 years, the motorcycles were discovered whole, in parts, and some were partially submerged under decades of dust, old machinery parts and household clutter. This is the last known collection of unrestored Brough Superiors; there will not be another opportunity like this. Only eight four-cylinder machines were built, and the example in this collection is the final one to be re-discovered.”

Perhaps the most interesting machine in Vague's collection is the 3-wheel Brough Superior with a modified Austin 7 engine (the 'BS4'), one of 8 produced, and the last one to be positively identified [see my Road Test of a BS4 here!]. George Brough felt the 4-cylinder engine was the ultimate ideal for a motorcycle, and of course Honda proved him right 40 years after he began making one-offs with four pots. The Austin-Brough was the only 4-cylinder BS produced in series, limited though it was; the others were the in-house sidevalve V-4 and 'Dream' flat fours, and a Motosacoche inline 4 scrapped when Bert LeVack died. All of these machines still exist. This newly discovered BS4 was the property of Hubert Chantrey, who rode it solo in the London-Edinburgh Trial, and was famous for riding his BS4 in reverse around Piccadilly Circus!

Bonhams will sell the collection next April 24th, at their Stafford Spring auction. There are links to each machine below the bikes, if you're looking for price estimates...but I wouldn't put much weight on those! Not a 'Brough guy'? Well, there are two HRD-Vincent Series A twins at the same sale, and a Coventry-Eagle Flying 8 with KTOR motor...it's going to be one hell of a sale.

Holes in the Memory

[Words: Paul d'Orléans. Originally published in Cycle World ]

When Sylvester H. Roper attached a small steam engine to an iron-frame ‘boneshaker’ near Boston in the late 1860s, he had no idea Louis-GuillamePerreaux was fitting a micro-steamer to a pedal-velocipede at the same time, in Paris. Kevin Cameron and I disagree on their species; he calls them ‘steam cycles’, but I think any motorized two-wheeler that delivers yeehaw is a motorcycle. That’s a scientific measure; the all-important Y factor. It’s what got both you and me and everyone else into bikes, even in the 1860s. Roper regularly rode his ‘self propellers’ around Boston, scorching the road between his home in Roxbury to the Boston Yacht Club, where he’d refuel and (presumably) have a beer. On June 1st, 1896, Roper was invited to demonstrate his steamer at the Charles River Speedway, a banked cement velodrome in Cambridge. He out-paced a peloton of bicyclists, then steamed away from a top pro racer. Track officials urged him to unleash the hissing beast, and after a few scorching laps timed at over 40mph, Roper wobbled, shut down, and collapsed. He was 72 years old, and had a fatal heart attack during a major yeehaw moment; he was the fastest cyclist in the world, and felt it keenly.

SylvesterRoper invented motorcycling; he was its first speed demon, and its first martyr. He’s our patron saint, and died for the same sin that stains 21st Century bikers - the lust for speed. His steam cycle of 1869 sits in the Smithsonian – their oldest powered vehicle, which they call a motorcycle – and the bike he died on sold for 500grand two years ago. He’s pretty important to the history of our second favorite pastime, and a hero of mine. So while visiting Boston last year, I was keen to follow the Roper trail, and asked Dave Roper (the first American to win an Isle of Man TT, and a distant relative) if he knew the address of his namesake? He recalled 294 Eustis St in Roxbury, but a visit in the company of photographer Bill Burke revealed a parking lot. I hit the Boston State Library, and found we were darn close – he lived at 299 Eustis St, and the house still stands. I told every Bostonian I met about this exciting discovery, and admit to crazy fantasies of buying the place, because Roper! If he’d created a cure for smallpox, or invented the automobile, or written famous novels in his day, you’d find a plaque by the front door, with the house listed in tourist guidebooks. But this is motorcycles, still a dirty word to some, so the house remains uncelebrated and overlooked, except now you know about it, too.

There’s little published on Roper, certainly no proper biography, just a few columns in 1800s magazines, and a lot of ‘web conjecture. The first motorcycle books weren’t published until the early 1900s, and all were ‘how to’ until Victor Pagé wrotea history of motorcycles in 1914. That might sound like the dawn of the industry, but ‘Early Motorcyclesand Sidecars’, which is still in print, was published 45 years after Roper and Perraux pioneered motoring on two wheels. Many thousands of books about motorcycles were published in the next 100 years, from ADV travel in the late ‘Teens (it was all adventure then), to tell-alls about 1%er club misadventures, to hundreds of histories of long-dead makes, from Aermacchi to Yamaha. But there are still big holes in the literature, and a lot of important stuff is missing from moto-history. I’ve been approached to write books on two brands this year – Zenith and Motosacoche – which in their day held World Land Speed records, won championships, and made a dent in their world. Researching those stories is hard work, but it feels good, like cementing the foundation of the House of Motorcycles. Put a plaque on it!"

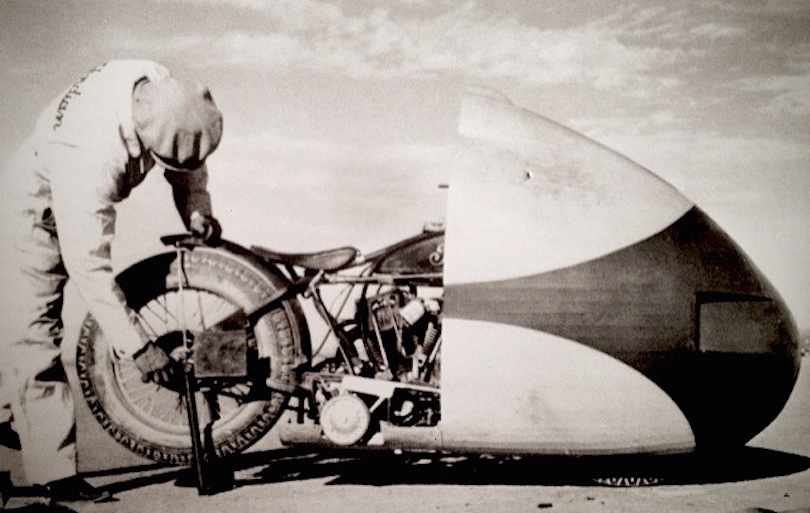

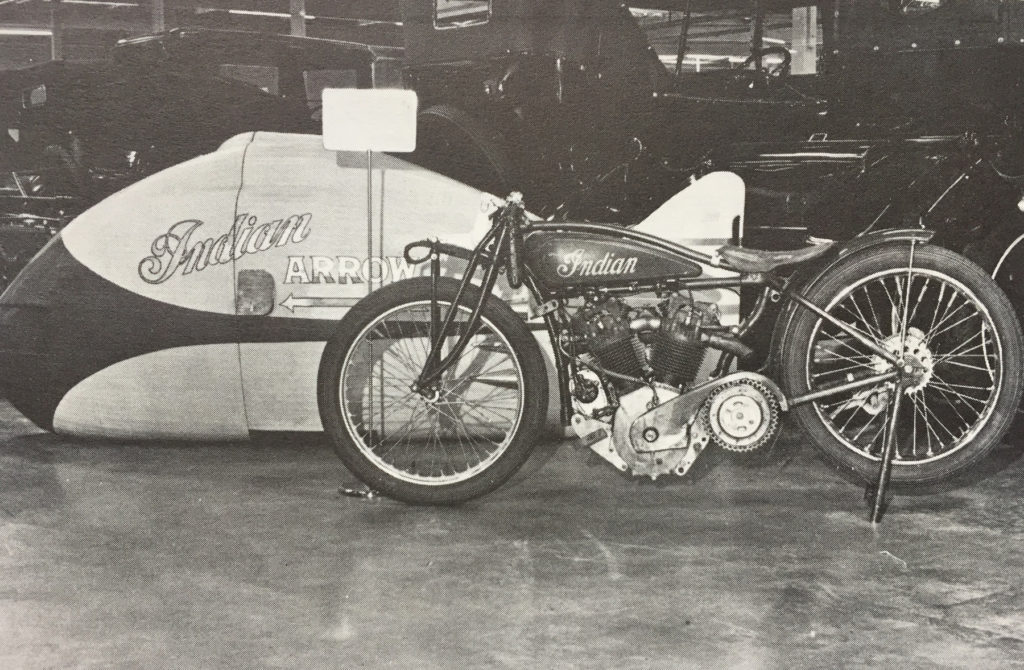

Shooting the ‘Arrow’

While Burt Munro's 'world's fastest Indian' is the most famous record-breaker to use Springfield iron as its base, it certainly wasn't the only Indian used in land speed record attempts. Let's not forget that the first-ever certified absolute motorcycle world speed record was set by Gene Walker on his 994cc Indian, at Daytona Beach in 1920. While he 'only' recorded a 2-way average of 104.21mph (167.56kph), this was faster than anyone else had done under the watchful eyes of a neutral (ish) sanctioning body - the FIM - who still oversee international records. Glenn Curtiss was timed one-way back in 1906 at over 136mph on the same stretch of beach, but it was an unsanctioned record, and not repeated in a return run.

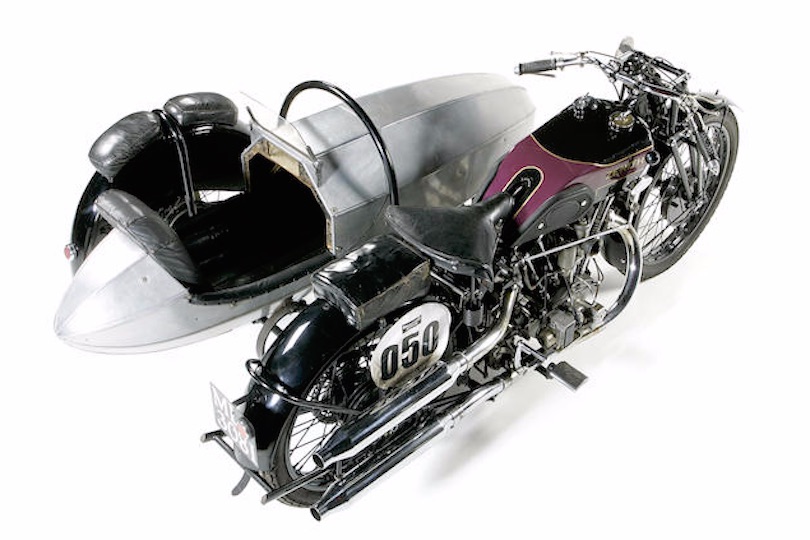

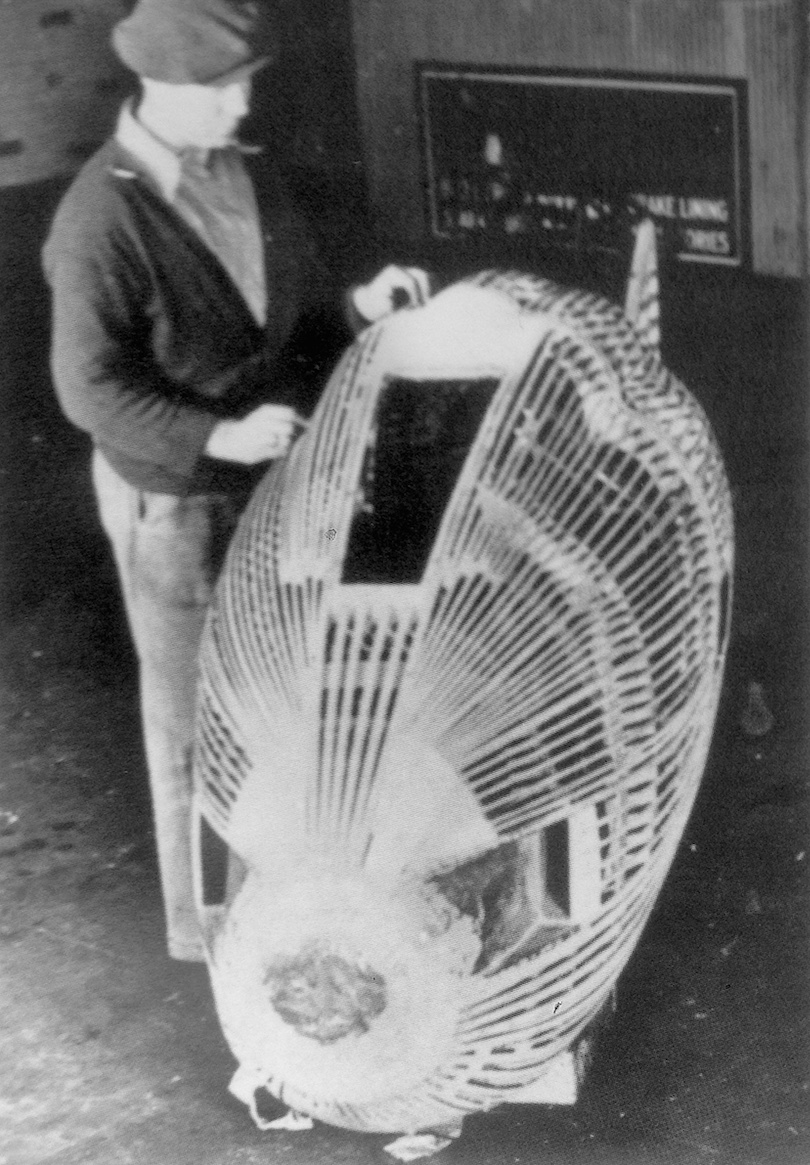

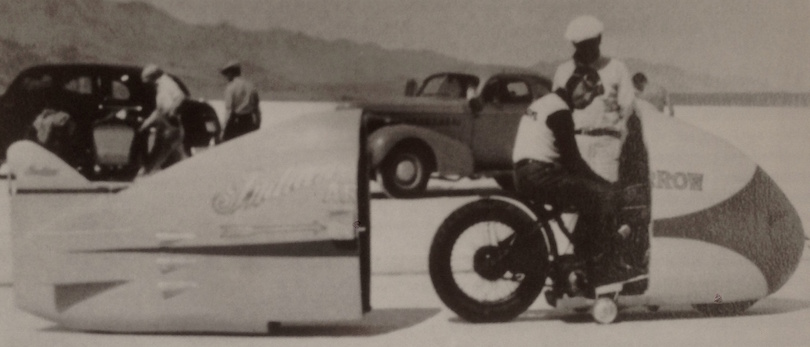

In 1936, Oakland Indian dealer Hap Alzina supervised the construction of a streamliner shell for another attempt to take the absolute honors for Indian. Alzina had secured a rare factory 8-valve 1000cc racing engine from 1924, one of a dozen built by Charles Franklin. These engines were capable of 120+mph speeds, running on alcohol, and it is supposed Alzina's engine was used to set the American speed record in 1926, with Johnny Seymour blistering along at 132mph. It seemed to Alzina that a bit of streamlining, as clad other world record machines (BMW, DKW, and Brough Superior specifically by 1936), could send the Indian name ot the top, especially as Joe Petrali had recently taken the American record on his modified 'Knucklehead' at 136.183mph - on a streamlined machine which had its body removed after it was found to be unstable. The last-generation 8-Valve engine was at least as fast as any unsupercharged motor then in existence, so in theory they had a chance.

Knowing streamlining was tricky business, Alzina hired an aircraft engineer (William 'Bill' Myers) to draw up and construct the very plane-ish body, which was constructed of balsa wood strips over plywood bulkheads, covered in canvas, and sealed with 'dope', just like a biplane. A chassis was constructed around the engine from a variety of Indian racing parts, with 1920 forks, a recent frame, and an older rear section, all of which was very light, as per their usual racing practice. The tank was from a '101' Scout, and the naked machine looked surprisingly coherent for a cobbled-up special. To economize on the timekeeping expenses, three machines were taken to the Bonneville Salt Flats for record-breaking: a Sport Scout, a Chief which had been stripped down to Class C rules, and Alzina's 'Arrow'. All 3 machines were in fact heavily 'breathed on' for the records, and the Scout became the fastest 750cc in the USA at 115.226mph, while the Chief managed an impressive 120.747mph, both Class C American records.

Fred Ludlow piloted the 'Arrow' in tests, and the ultra-light weight and racing chassis geometry of the bike did the attempt no favors. That the streamline shell was untested, and also very light, was also bad news, and while the bike was very fast indeed, it proved unstable above 145mph, weaving and tank-slapping until it was blown off course, and realizing the shell was unsuitable, the attempt was scrapped. It's easy in hindsight to diagnose the flaws of their machine, but Alzina was a private dealer with a little factory help, and not a well-funded, factory-backed racing effort. It was clear the project needed a lot more work, but he'd spent a bundle on the machine already, and ultimately decided to shelve the project and concentrate on Class C racing, hillclimbs, and selling motorcycles. The 'Arrow' languished in Hap Alzina's back room for decades, and it was eventually purchased by the Harrah's collection in the 1970s. It certainly exists today, and photographs show a compelling motorcycle, almost a 'resto-mod' with those early loop-spring forks, and one which every Indian fan wishes they owned!

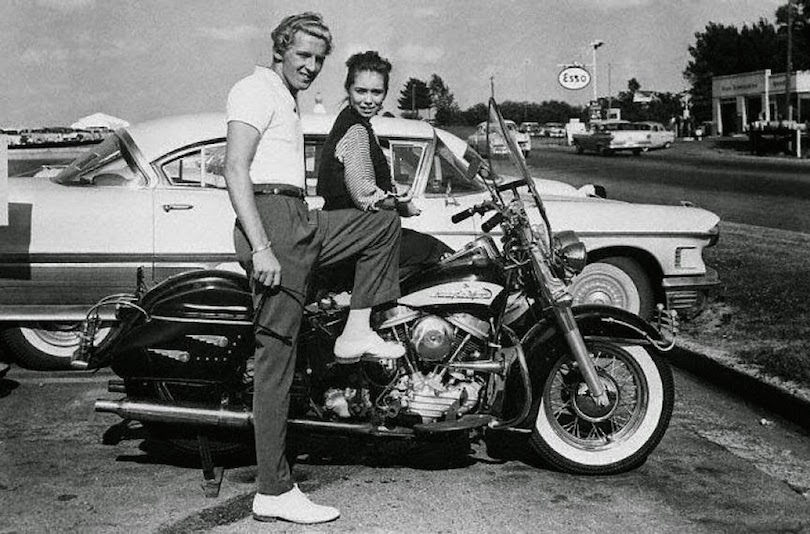

‘The Killer’s’ Panhead Tops $385k…

At Mecum's Kissimmee auction yesterday, Jerry Lee Lewis' 1959 Harley-Davidson FL 'Panhead' which he's owned for 55 years, and was a gift from the Harley-Davidson factory, sold for a remarkable $385k, including fees. This places his Harley at lucky #13 on my 'Top 20' list of the World's Most Expensive Motorcycles; wholly appropos. I was asked to interview 'the Killer' and provide text for the auction, which is below:

"Rock n’ Roll legend Jerry Lee Lewis has an outsize reputation as a larger-than-life character living with scant regard for public opinion. Regardless of debauched tales and extreme behavior, this electrifying showman not only climbs onto pianos, but also motorcycles…which should come as no surprise at all. In the 1950s, he seemed the most‘at risk’ performer of all, pioneering a new musical style with an aggressive, almost wild stage presence, as well as the original “sex, drugs, n’ rock n roll” lifestyle…yet he remains alive today, still performing on occasion, and still with a clutch of Harley-Davidsons in his stable.

Lewis bought his first motorcycle – well, a Cushman scooter – at 16 back in 1951, when he “wasn’t big enough for a real bike”, using money he earned working on his father’s farm. But ‘farm work’, and the Cushman, wouldn’t last long; his first hit record from the historic Sun Studios dropped in 1956, ‘Crazy Arms’, which sold 300,000 copies, mostly in the South. The next year, ‘Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On’ spread like a grassfire across the globe, and as a gift to himself, Lewis purchased a brand-new, blue 1957 Harley-Davidson FLH ‘Panhead’, with the big 74” motor. “It was a fine motorcycle, and I rode it all over the place. When I put out my first record is when I bought that bike.”

Jerry Lee Lewis was at the peak of his early career in 1958, having already sold millions of records, and established himself in the Rock ‘n Roll firmament alongside Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Gene Vincent, and Little Richard. The Harley-Davidson factory, always savvy with ‘product placement’, gifted a pair of new 1959 FLH Panheads to Lewis and Elvis Presley. Jerry Lee got his first, which irked The King; “Harley-Davidson asked if I’d like to have a new bike, and they brought it down to Memphis and gave it to me at my house. Elvis got the second one, and there was a bit of personal talk about this – he couldn’t understand why he got the second one, so I asked if he wanted to trade! That was just a joke.”

Lewis really enjoyed this ’59 Panhead, “It’s a fine motorcycle, no comparison to my ’57 Panhead - the motor on that one wasn’t quite as nice. This motor is just as good as the day it was given to me.” Asked why he’s selling a precious piece of personal history he’s owned for 55 years, Lewis becomes pensive. “There was a time I wouldn’t take a zillion dollars for it, but now it’s just sitting there. You can crank that motorcycle up and she purrs like a kitten – but you have to kickstart it you know. I could probably sit on it alright today, but I wouldn’t take a chance. I’m 79 years old. This bike is like a child to me, but I’ve decided it’s time to let it go.”

Jerry Lee Lewis’ loss is a memorabilia collector’s enormous gain, as few celebrity motorcycles have such an indelible association with a notorious and legendary owner. ‘The Killer’s ’59 Panhead, looking fresh as the day the factory gave it to him, still in his ownership after 55 years; it doesn’t get any better than that, and likely there will never be another classic Harley for sale with such solid gold provenance. If that doesn’t leave you ‘Breathless, Honey’, it’s time to check your pulse."

In the 'now it can be told' file, Lewis admitted a big reason he was selling the Panhead was to prevent a family feud after he dies, with many heirs clutching at whatever fortune he's retained after half a century. He still has one bike, a Sportster, which he's revved up on stage in the past, and now sits in his Florida restaurant.

Here's a video of the auction sale:

BMW Path 22: Hanging Ten on the Trends

[Words: Paul d'Orléans. Originally published in Cycle World]

While in the south of France for the Wheels&Waves festival last week, BMW revealed its concept surf-moto, the 'Path22' - a reference to the forest service road Vincent Prat takes to his favorite surf spot north of Biarritz. With paint by Ornamental Conifer and a custom surfboard by Mason Dyer, Path22 is a lovely homage to an event which has become the premier alt.moto festival in the world in just 4 years. Here's the article I wrote for CycleWorld.com.

The Southsiders MC, organizers of the Wheels&Waves festival in Biarritz, have been tearing up the Basque Pyrenees every June since 2009. There were 10 of us that year, and six years later the gang has grown to 10,000. The first official edition of Wheels&Waves appeared in 2012, and was modest by comparison, but smelled of gunpowder. The artists, writers, builders, and publishers who participated knew something was up, and it was only a matter of time before the rest of the world felt the blast.

BMW was the first brand to sign on with Wheels & Waves the following year, as ‘Sonic’ Seb Lorentz (of Lucky Cat Garage) cajoled his bosses at BMW France to literally take a stand. It was a shrewd move, and their presence has grown yearly, first bringing historic machines to display (a pair of Ernst Henne’s supercharged world speed record missiles), then revealing special collaborations, like the Blitz R9T custom, with the world’s first 3d-printed fuel tank.

This year BMW’s big reveal was the Path 22, an in-house collaboration with artist Nicolai Sclater (Ornamental Conifer), who hand-painted an appropriately fun Wheels & Waves scheme on a Scramblerized R NineT. Mason Dyer was commissioned to shape a board to haul alongside, on a special factory-made—but sadly not catalog-offered—surfboard carrier. When pressed about the missing wetsuit pannier, BMW Motorrad’s chief designer, Ola Stenegard, rolled his eyes and laughed. “I know. But then we’d have another one-off piece to explain we’re not going to produce,” he remarked. Too bad—the carrier was beautifully crafted, and surfers would benefit from a proper accessory instead of some cobbled up contraption with duct tape.