To understand the slow and chaotic beginning of the Japanese motorcycle industry, it helps to understand a little of the country’s background, and history of its relations with the West. Japan was never isolated or ignorant of world affairs, having conducted sea trade for centuries with neighbors in China and Korea, and was well aware in the 1500s that an aggressive colonial expansion by European countries had begun in the New World. When Spanish and Portugese traders arrived on Japanese shores in the late 1500s, the introduction of Catholicism in southern Japan was seen as the spearhead of a possible colonizing effort by Europeans. In response, the Tokugawa shogunate (the feudal military rulers in Edo castle – this is also called the ‘Edo period’) passed laws starting in 1633 which drastically restricted contact and trade with the outside world, making entry into Japan by foreigners, and exit from Japan by locals, punishable by death. These laws remained in effect until 1868 (230 years!), the end of the Edo period, and the start of the ‘Meiji Restoration’. As with all politics, while the colonial threat was the primary excuse for an iron grip on Japanese trade, an important effect was to enrich the Tokugawas and deprive rival feudal groups of trade revenue. Ultimately this unified Japan, and created a national identity.

Japan still traded with the outside world, through tightly controlled channels: the sole European access was limited to the artificial island called Dejima, in Nagasaki harbor, where the Dutch East India Company handled imports and exports. All trade with China went through Dejima as well. Trade with Korea, the Ainu people of northern Japan, and the islands of the Ryukyu kingdom (Okinawa etc) were all handled at specific sites. Europeans tried for 200 years to establish relations with Japan by trickery or force, but were successfully repelled until July 8, 1853, when Commodore Mathew Perry brought four US Navy warships (the kurofune, or ‘Black Ships’) into Tokyo Bay, and broke the resistance of Japanese forces. He returned the following year with 7 warships, and forced the Shogun to sign ‘Treaty of Peace and Amity’…classic ‘gunboat diplomacy’; the treaty forbade the Japanese from levying tarrifs on trade (although of course the US could), and gave US citizens immunity from prosecution in Japan (‘extraterritoriality’ – same as in Iraq/Afghanistan today – some things never change). Such treaties were implemented soon after by European countries, a humiliating turn of events which led to the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, which was replaced by the Meiji oligarchy in 1868 [which corresponds to the invention of the motorcycle, in France (the Perraux steam cycle) and the US (the Roper steam velocipede)].

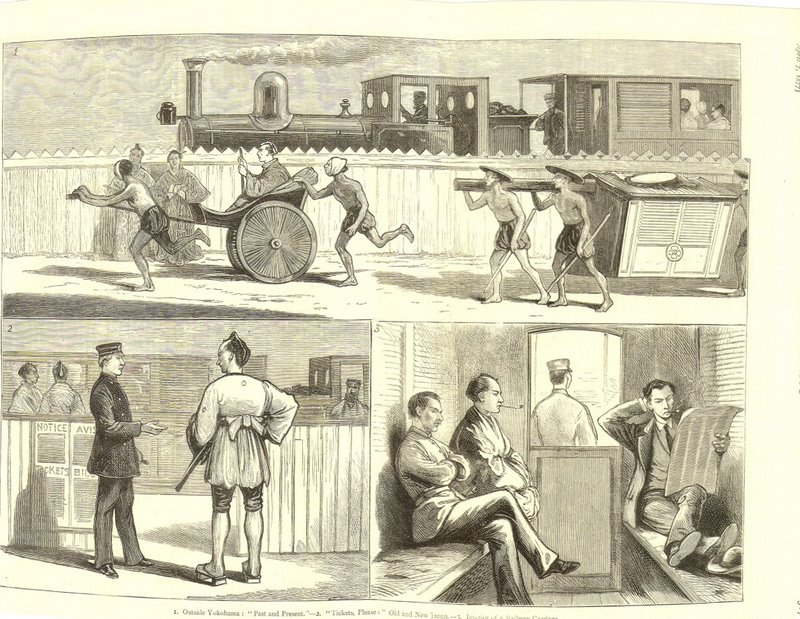

The sudden/forced opening to European influence was embraced by the Meiji government, who saw modernization as the only way to defend Japanese sovereignty and culture. They organized ‘learning expeditions’ to the US and Europe from the 1870s onwards, where large teams of diplomats and students examined all manner of manufacturing and governmental institutions (military, courts, schools, etc). These missions served Japan well, for within a generation the country had become acknowledged as a modern global power, with a burgeoning industrial base.

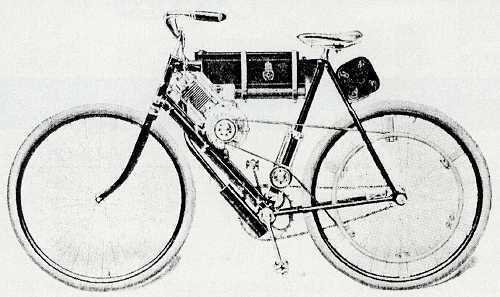

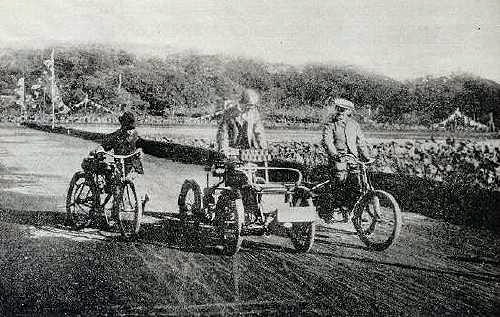

The first motorcycle appeared in Japan in 1896; a Hildebrand and Wolfmüller imported by Shinsuke Jomonji, a member of the Japanese House of Representatives, who demonstrated the machine in front of the Hibiya Hotel in Tokyo (destroyed by earthquake in 1923?). In 1901, a Thomas motorcycle and tricycle were imported, and the motorcycle was ridden extensively through Tokyo, and generated considerable press comment. The first motor vehicle race in Japan was staged between the two Thomas machines and a Gladiator quadricycle, on Nov. 3, 1901. The Thomas is generally considered the first production motorcycle in the US, and its appearance in Japan at this early date is remarkable.

1908 – The First Japanese Motorcycle:

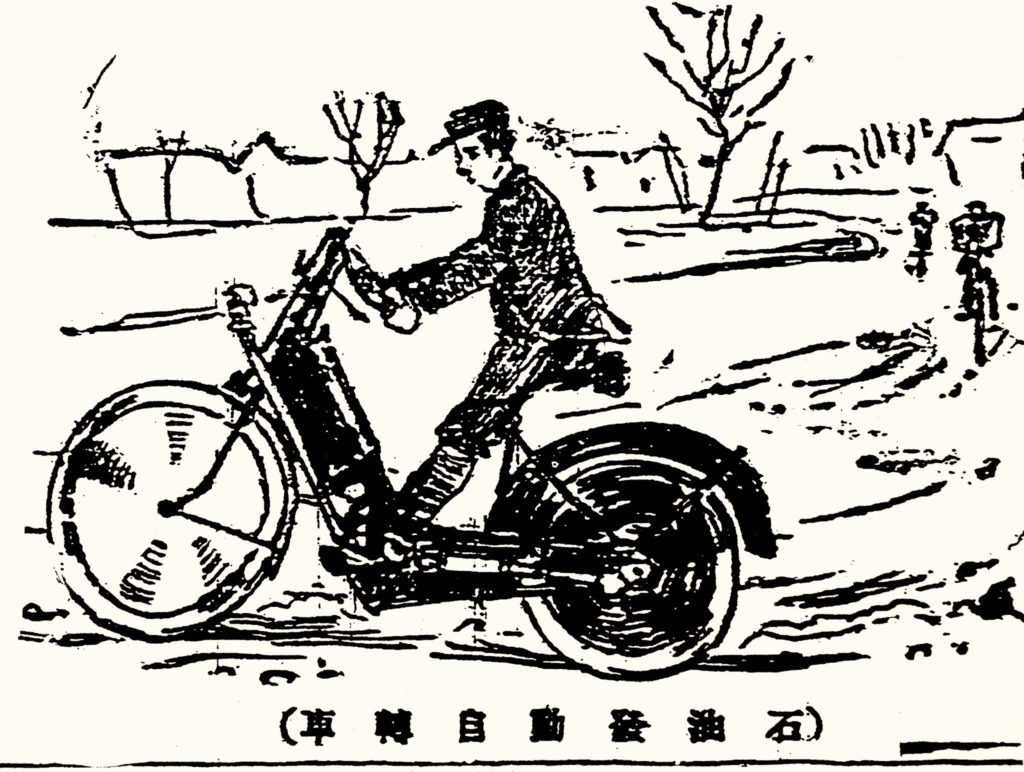

The true pioneer Japanese motorcycle builder was Narazo Shimazu, who established the Shimazu Motor Research Institute in 1908, in Osaka. Using knowledge gleaned from Scientific American and the English book ‘Motor Cycling Manual’, he built his first gasoline-powered engine in August 1908, a two-stroke single-cylinder of 400cc, and installed it into a home-built frame from salvaged bicycles (there being no raw tubing available) – the first entirely Japanese-built motorcycle

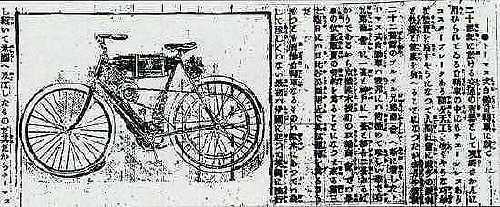

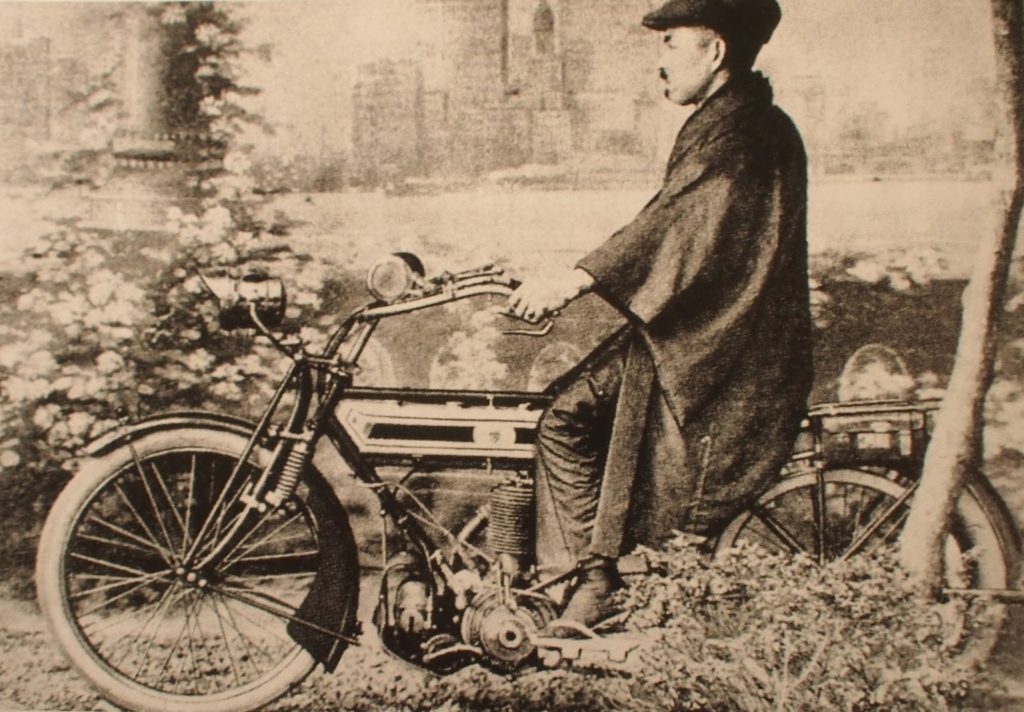

In 1913, Eisuke Miyata, founder of a gun and bicycle firm (in 1892 – ‘Miyata’ is still making bicycles today), purchased a Triumph and made a faithful copy as the ‘Asahi’ motorcycle, which was used by the Tokyo police and for gov’t minister escort duty, despite its 180yen price. The Japanese motorcycle industry had truly begun, although there was as yet no unified highway code in Japan, and inter-urban roads were terrible. Urban roads were worse, as Japanese cities were intentionally built in a crazy-quilt pattern during their Feudal period, to slow the advance of invading troops. A lack of road signs and even street names, combined with the horrific state of road repair, made the advance of motorization difficult. Japan had never relied on horse and carts for general movement of goods in their Feudal period, and almost all traffic was by foot.

Narazo Shimazu returned to the motorcycle business in 1926, producing the ‘Arrow First’, a 250cc sidevalve single-cylinder, and after 6 were built, he embarked on a well-publicized across-Japan moto-tour, sponsored by Japan Oil, Dunlop, and Bosch. Six riders, on four red motorcycles, took a 15-day ride of 1430 miles from Kagoshima to Tokyo. The publicity drew the attention of the Ohayashi group of companies, which whom Shimazu founded Japan Motors Manufacturing. He improved the ‘Arrow First’, and eventually sold 700 over the next 3 years, before the business went bust.

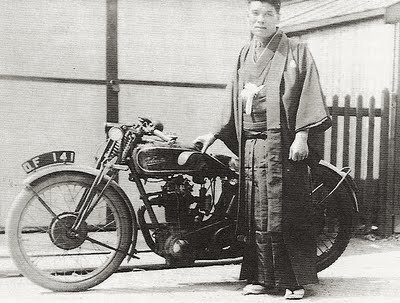

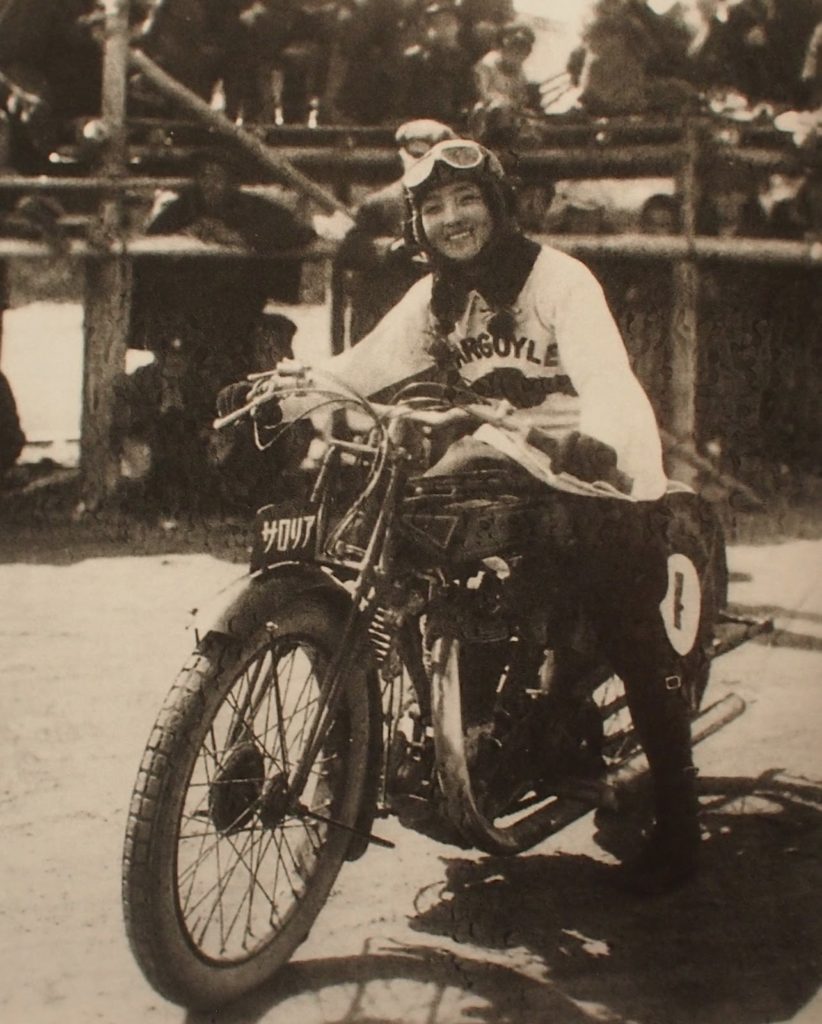

The first motorcycle race in Japan was held in 1913, at the Hanshin Racecourse, a dirt horse racing track in Nishinomiya (near Kobe). Around 30,000 spectators attended, a record for any kind of race in Japan. Racing became more common at venues across the country, and professional riders emerged, such as Kawamada Kazuo (who worked for Alfred Child at Harley Davidson Japan – see below) and the remarkable Kenzo Tada, the first Japanese rider to compete at the Isle of Man TT, in 1930, aboard a Velocette KTT. [Read more on Kenzo Tada here]

Just like the United States after WW2, it was the need for military mobility which sped up infrastructure improvement for Japanese roads. An increasingly belligerent Japanese military (annexing Taiwan in 1895, and parts of China and Korea by 1910) used motorized vehicles in greater numbers than the rest of the country. By 1919, a unified highway code was established along British lines (meaning they drive on the left), and civilian contractors hired to improve roads and bridges, while the military was allowed to subsidize vehicle manufacture at home.

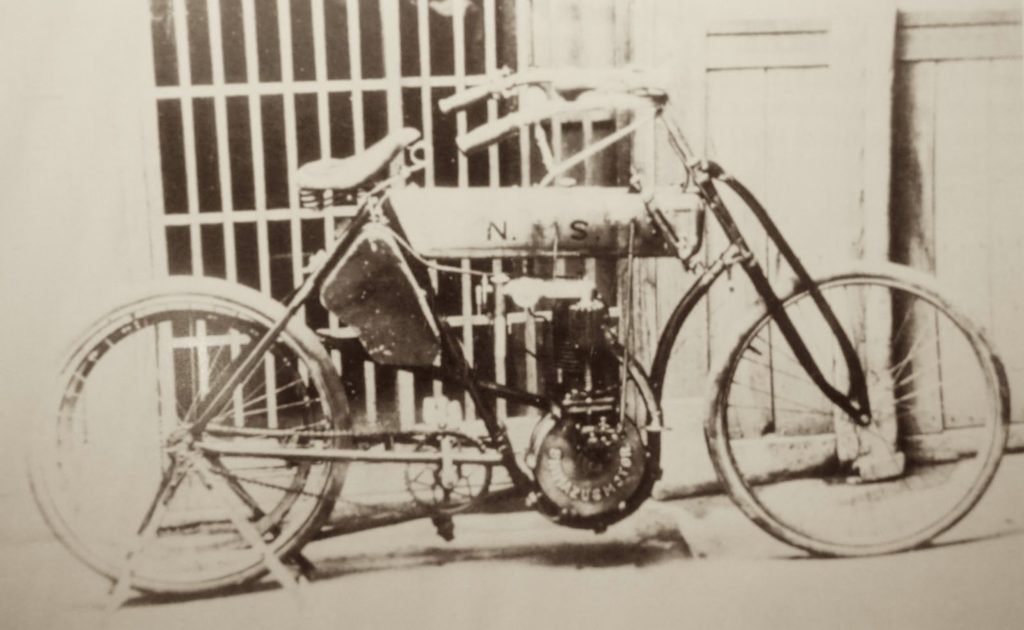

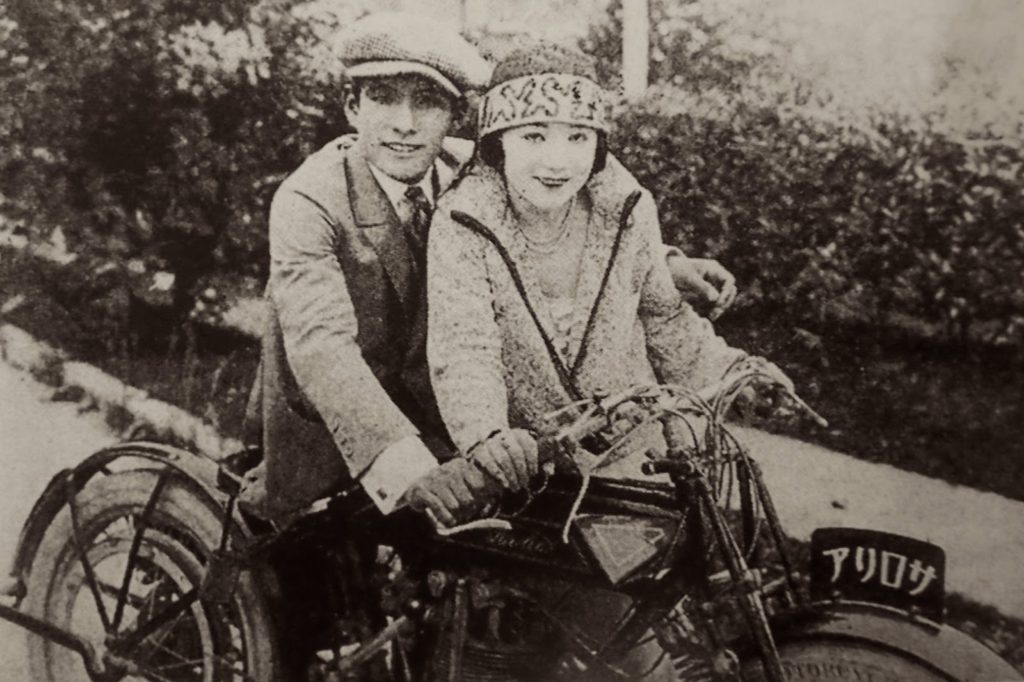

During the 1920s, Japanese textiles were driving their export market, and increased prosperity meant more imports of motorcycles. Harley Davidson’s #2 global export market in the 1920s was Japan (after Australia), and Indian sold just as many (around 1000/year), including to Prince (later Emperor) Hirohito, who enjoyed riding an Indian Chief with sidecar. Henderson four-cylinders were also sold in Japan, and manufacturers from Britain (AJS, Matchless, Norton, Douglas, Brough Superior, and Velocette), Belgium (Saroléa and FN), plus Husqvarna, Moto Guzzi, NSU and BMW exported to Japan as well. The Road Improvement Plan of 1920 estimated a 30-year project of completely paving Japanese roads, and building bridges over rivers, and the motorcycle as a pleasurable touring machine for wealthy riders became a reality. Motorcycle clubs sprung up, some of which forbade riders to venture alone due to the terrible state of roads, and a culture of tonori (‘riding far’) grew.

A massive earthquake destroyed much of Tokyo in 1923, killing hundreds of thousands, and the utter lack of motorized emergency vehicles, plus the impossibility of the road system for efficient rescue/reconstruction work, meant big changes for the Japanese vehicle industry, and the roads they used. Tokyo was rebuilt with a more rational road system, which doubled the number of vehicles in a single year (1924), and led to a push country-wide for a modernized road system. To further promote the nascent Japanese vehicle industry, import tariffs were imposed on foreign vehicles in 1925, which led Ford (1924), General Motors (’27), and Chrysler (’29) to establish factories in Japan. Harley-Davidson followed suit in 1929.

Several small motorcycle manufacturers set up shop in the mid-1920s, including the 350cc two-stroke Sanda (‘Thunder’) from Osaka, the SSD of Hiroshima, and the grand-daddy of them all, a 1200cc twin called the Giant, built by Count Katsu Kiyoshi in 1924. The Japan Automobile Company (JAC) produced motorcycles starting in 1929, which included 350cc and 500cc sidevalve singles, and a 500cc v-twin on JAP lines. In 1931 JAC built about 30 examples of 1200cc flat-twin, used for Imperial escort duty. Between the late 1920s and 1937, when the military effectively commanded all civilian vehicle production, quite a few large manufacturers had firmly established themselves in the Japanese market. Maruyama, Toyo (Mazda), Meguro, Cabton, Showa, Miyata, and Rikuo. Miyata alone produced nearly 30,000 motorcycles between 1930-45, and as mentioned, Rikuo built some 18,000 heavyweight H-D clones between 1935-42.

Information and photographs for this article were sourced from 3 excellent books:

– ‘A Century of Japanese Motorcycles’, by Didier Ganneau and Francois-Marie Dumas, which is to date the only comprehensive English-language book covering all years of the Japanese motorcycle industry. Given the market dominance of Japanese motorcycles since the 1960s, this is a remarkable poverty of books, compared to every other nation’s motorcycling contribution. Photos scanned from here are listed as (Iwatate). It’s a must-own book!

– ‘Japan’s Motorcycle Wars’, by Jeffrey Alexander, was reviewed in The Vintagent here. An excellent dissertation, admittedly not a ‘bike book’ per se, but full of good stuff.

– ‘Harley Davidson’ by Harry Sucher, for the Rikuo story; the first complete history of the H-D marque, with much info from people who were still alive in the early days. Extremely informative. Photos listed at (Sucher).

GuitarSlinger said…

Brilliant Paul . A short education on Japanese M/C history for the masses ( in light of the reference books being a bit dry and obscure ) and a better response to Cyril’s recent article .

Articles like this is why I frequent the site good sir !

Chas said…

As an ex-HD factory test engineer I loved your article. As far as I’ve learned, it’s dead nuts accurate.

In the 1980’s “The Cage” contained an old telescope suspension equipped WL/Rikuo.

Sir—

Thanks so much for the wonderful story on the Japanese motorcycle scene.

I do hope you will continue this wonderful story and provide us an ongoing account that includes the early days of the Honda motorcycle.

After seeing one of those very early Honda bolt on motors I couldn’t rest until I got an old bolt on motor myself—except mine is a Vincent Firefly. Guess I’ll make do…!

Kris TigerLady

Interesting piece!

– Randy Neil Stratton

Very interesting write up, thank you sir.

– Michael Alton

Great read Paul.

– Jim Dickerson

Great job! Great treatise on the early Japanese motorcycle history.

Wow. Paul, you never cease to amaze. As a guy that dreams of owning a vintage bike someday, you continually demonstrate how much there is to learn. Right now an old 91 Softail, purchased new, is as close as I’ve made it to a vintage bike. Still watching and trying to learn.

Kudos for the history lesson.

Great in depth article Paul. I figured there was much more history there than I’d previously heard!

As usual great article Paul.

Thanks Paul, your site is amazing.

Great read.

Very interseting and educational on the Japanese motorcycle history.

Thanks a lot.

Fascinating subject. I’m really interested in the history of the Japanese Motorcycle industry and have read both of the books you mention. I also edited and co-wrote a shorter book called “100 Years of Japanese Motorcycles” for the Vintage Japanese Motorcycle Club about 13 years ago and I have a few posts on my own blog about the subject, like this one here http://blackcountrybiker.blogspot.co.uk/2011/02/1950s-vintage-japanese-motorcycles.html Thanks again for such an informative and educational blog – I don’t know where you find the time.

Paul, what a beautiful coverage story. Thanks very much.

This is a topic that is close to my heart…

Best wishes! Exactly where are your contact details though?

Cool bitches! They are in such good quality for being so dated. There is so much history in each picture its amazing.

Stumbled across your great history and read it with enjoyment.

“Give big space to the festive dog that shall sport in the roadway.” (I trust you’ve seen that famed comment, from a 1930s Japanese police manual on driving in that country).

From the early 1960s until the end of the decade I was involved with the industry, working with Kawasaki as they acquired Meguro, Tohatsu and (as I recall) Bridgestone. The “heavy industry” guys knew extremely little about motorcycling, which is why the early Kaws had fantastic engine/tranny units and sort of by-guess-and-by-god running bits (mostly in the Meguro tradition – farmer’s bikes).

Eventually I was hired by the late Ivan Wagar as JAPAN CORRESPONDENT for Cycle World, but found that most hot info and secrets leaked out of the US (California) representative companies. Still it was a great time and I was even sponsored by Pop Yoshimura at the 1966 Japan Grand Prix, where I earned my sole world points.

Thanks again for your sterling efforts.

Byron Allen Black

Parakansalak, West Java

Dear Sir,

I have recently found a 1925 Japanese

‘Two-Cycle No-Water Injection Motor Handling Code” (google translate app).It is in not mint but OK condition.I am wondering if there is a market for this kind of manual and I happened on your blog. This looked so interesting I couldn’t throw it away.

Tess B

Hi Tess B,

It’s quite hard to say whether there would be any interest in this document but if you had the time and patience you might want to try listing it on eBay or a similar on-line commercial outlet. I’d ‘start high’, maybe around $500, and then come down if you don’t get any nibbles. I have had similar thought for a couple of original Beat-era publications I have. Found out they were worth a LOT less than I’d imagined.

Excellent read Paul. Most informative. I have two of the books you have referenced, “A Century of Japanese Motorcycles” and “Japanese Motorcycle Wars”. Both well written as well. I thoroughly enjoyed your article.

Thanks! I find it fascinating that Harley-Davidson didn’t tell the story of its Japanese savior during the Depression until the 1980s, and even then it was kept very low-key. They have never confirmed the dollar amount that was paid, although I reckon Harry Sucher had good sources in H-D, who provided an accurate accounting.

I’m digging a bit further into the Kishichuro Okura story, but as it’s automotive, any resulting article it will probably appear in the pages of The Automobile magazine…