With her struggles and triumphs as a pioneer professional motorcycle racer, Taylour ought to be lauded as a feminist hero…but with some heroes, digging beyond the headlines reveals a far more complex character, and in Taylour’s case, a deeply troubling story. Fay Taylour, born in Ireland of British gentry, embraced Fascism in the 1930s, in common with a other notable bluebloods, like the sisters Unity and Diana Mitford (married to Sir Oswald Mosley, 6th Baronet of Ancoats and founder of the British Union of Fascists). We would love to celebrate Taylour, but her unrepentant promotion of Fascism makes her an impossible figure. The story of her remarkable success on a motorcycle is forever colored by her conscious adoption of an ugly and hateful ideology; even before Nazism became genocidal, hatred of the Jews, people of color, queers, Gypsys, and Leftists was a foundation of Hitler’s ideology, and sending these groups to death camps was a logical extension of the political philosophy spelled out in his 1925 book ‘Mein Kampf’. Even after evidence of the concentration camps filtered to the world, Taylour remained unmoved, kept a photo of Hitler on her bedside, and was vocally anti-Semitic. Her Fascism began 8 years after her last speedway race, but cost her the enduring fame she’d earned as a woman in a ‘man’s world.’

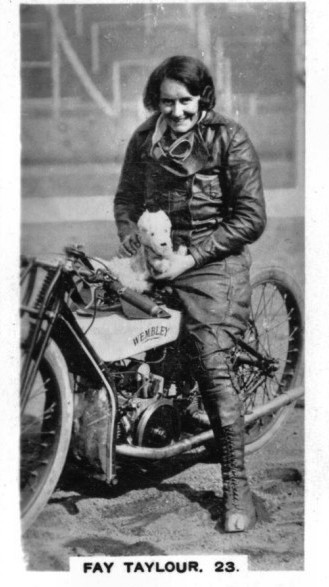

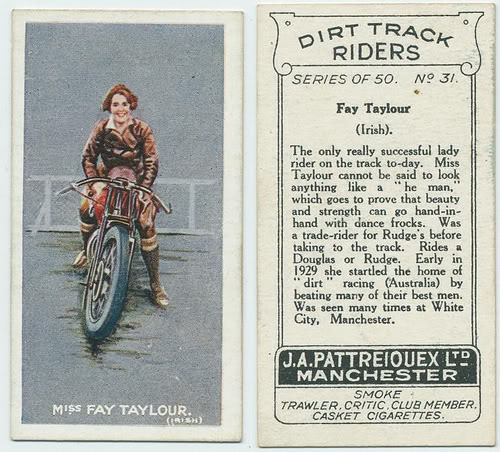

Francis Helen Taylour was born 1904 in Birr, Ireland. She was extremely competent physically, and loved to hunt, fish, and ride horses. Her father was an officer in the Royal Irish Constabulary, and she learned to drive his Buick at the age of 10, and was a competent driver by 12. She was a champion bicyclist at her girls’ school (St Trinian’s), and after her mother died, she gave up academic pursuits to live with her father, who’d retired to Burghfield, a small town in Berkshire. There she met a mechanic who became a love interest, but he had a Rudge and taught Fay to ride. She soon bought a Levis 220cc two-stroke, then an OHV AJS K6 ‘Big Port’ single in 1927. A local motorcycle dealer, Carlton Harmon, observed her skill on a motorcycle, and encouraged her to enter the ‘Southern Scott Scramble’ at Camberley Heath, near Reading. The Scramble was a 24-mile circuit run twice, with a ‘Venus Cup’ for best woman rider, which Harmon suggested Taylour could win. Harmon gave her instruction, and suggested she ride as she was inclined, which was ‘flat out’. She practiced the course daily before the event, to master its several steep hills, ‘Wild’, ‘Wooley’, ‘Kiliminjaro’, and Camberley. She wore a distinctive oversize man’s cap while riding, and during official practice for the Scramble, Jimmy Simpson and George Rowley, both factory-backed racers, couldn’t keep up with the rider in the unusual cap – who they later discovered was a girl. She won both the ‘Novice’ and ‘Venus’ cups, in her second-ever motorcycle event.

She soon won Gold Medals in the Leeds £200 Trial, the National Alan Trial, the Travers Trophy Trial, and silver in the Colmore Cotswold and Victory Trophy Trials. She even won a Gold Medal in the ACU’s Six Days Trial, run over a 750-mile route, and quickly gained a reputation for remarkable personal endurance and tremendous skill at handling a motorcycle. In only four months of Trials competition, she had earned enough prize money to live on for the year, and soon looked for work in the motorcycle industry in the Midlands. She landed a job at Rudge as a secretary(!), but was selected to ride with the factory Rudge Trials team for 1928, and given a 500cc four-valve competition model. She promptly won the Ladies’ Award in the London-Gloucester-London Trial, but lost the speed test, as a compression plate had been added below her Rudge’s cylinder barrel. For her next trial, she worked until 3am removing the plate and rebuilding the motor in her hotel room, then rode that morning without a single loss of marks…but had to be content with a Silver medal – the same as her male factory teammates – as she’d lost 50 points for arriving late to the competition.

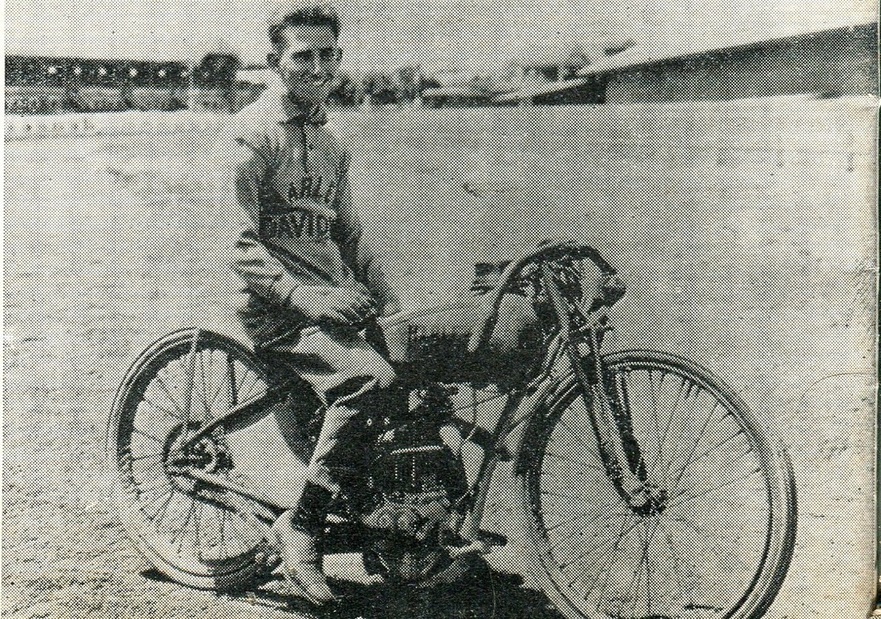

In 1928, she observed one of the first dirt-track races in the UK, at Stamford Bridge. She watched amazed as the American rider ‘Sprouts’ Elder broadslid his Douglas racer around the horse track. Fay immediately made the rounds of various dirt tracks, asking to be given the chance to ride. All refused her, but she was typically undaunted, and went to Lewis Leathers in London to have a racing suit made to measure. While there, she met Lionel Wills, a genteel tobacco heir who loved fast motorcycles, and had learned to broadslide after watching races in Australia. The pair had a long relationship, and Wills helped Taylour make her way in the dirt-track world, partly as Wills himself had brought the sport to Britain after witnessing a dirt-track race in Sydney, Australia, and became the first cinder-track racer in the UK. He wrote articles for sports magazines back home describing the new sport, and worked with Johnnie Hoskins to bring Australian riders to the UK to seed the sport on British soil.

Taylour fitted a hook to her works-supplied Trials Rudge, in defiance of the factory, and wore a face mask with her leathers (common, to keep the cinders out) and snuck into an open practice session at Crystal Palace. She rode and fell repeatedly, but after a full day of trying, she started to broadslide. When Lionel Wills told track manager Freddie Mockford that the irrepressible rider practicing on his track was female, he nearly spat his cigar. But Wills lied that she’d been signed up at ‘all the other tracks’, so Mockford gave Taylour a week to practice before the next race. She wired Charles Vernon Pugh, the Managing Director of Rudge, to support her with a dirt-track racer, and when he refused, she purchased a Douglas DT5 racer. But before it came, she rode her modified Trials machine, which was far heavier than the specialist dirt track models being hurriedly offered by almost every manufacturer. Still, she proved her skills on the track, and more importantly was a huge draw at races, and the press had a field day with ‘Eve on the Sport Field’ headlines.

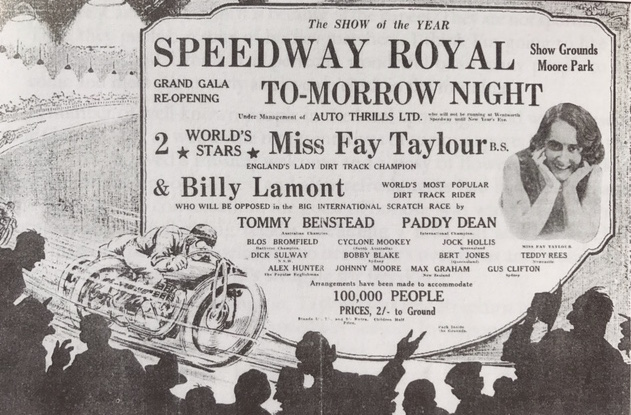

In 1928, Taylour was the first dirt track racer from Europe or the USA to travel to Australia, the home of the sport, to compete with the legends Down Under. She first landed in Perth, where she trumped the ‘unbeatable’ Sig Schlam on his home track, equalling the track record, then went to Melbourne, where she trounced the local hero Reg West, and held the lap record at his track for a year. After a successful tour of Australia and New Zealand, in which she was heavily advertised in advance of races with tens of thousands of spectators, she returned to Britain and won the Cinders Trophy for the fastest lap in an International contest, in front of a crowd of 30,000. At a race in Southhampton she even beat Sprouts Elder, the legendary American dirt-track expert, who would shortly follow her example and create a global speedway circuit between Argentina, New Zealand, Australia, the USA, and Britain, following the weather between hemispheres and riding seasons.

Taylour returned to New Zealand and Australia after the end of the UK riding season in late 1929; she was greeted as a star Down Under, and promoted as one. She defeated the New Zealand champion (Mattson) and recorded FTD at Auckland, then took .8sec off the lap record at the Dunedin track, beating the local champion (Young). She returned to the UK in Spring of 1930 to discover that women had been banned from the dirt tracks, and in May 1930, women were banned from riding speedway in Australia too! According to Taylour’s biographer Brian Belton, it wasn’t the promoters and riders who stopped women racing, it was the insurance companies who feared the reaction if a woman was killed in a race.

Banned from doing what she loved, she turned in 1930 to racing cars. For the next 24 years she had various successes, setting a record on the ‘Rianchi Run’, a 300-mile course from Calcutta, driving a 1931 Chevrolet, which gained her an entry at Brooklands in late 1931 aboard a Le Mans Talbot 105, in a women’s race, which she also won. She won the Leinster Trophy in Ireland in 1934 (driving an Adler Trumpf), and won the Hill Circuit Trophy at the Shelsey Walsh hillclimb. She won a women’s race at Donington, competed in the Mille Miglia, and again at Brooklands with a Alfa Romeo 8C Monza, coming in second after lapping at 114mph. She was so full of excitement driving the Alfa that she continued hot lapping the circuit after the race, and had to be stopped by a flagman stepping in front of her car; she thought it a great joke, but she was disqualified from the race and fined.

In Septermber 1939, Britain declared war on Germany, and Fay Taylour became outspoken in her support of Hitler, and against the war. She had visited Germany many times since 1928, driven factory-loaned Adler race cars, and gotten to know officials in the NSKK (Nazi sport bureau). Her anti-war, pro-German advocacy was unattached at that point to any organized political party, but she played a German radio station loudly to annoy her neighbors, and proclaimed her views in restaurants, in letters to friends, and to newspapers, as well as with (illegal) leaflets she distributed. All that earned her a visit by the Special Branch of the Metropolitan Police in 1939, which only increased her public support for Hitler, and she soon joined Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists. She also attended gatherings of the Right Club, and after Club member Tyler Kent‘s arrest for spying (he’d stolen 2000 secret telegrams between Churchill and Roosevelt), Defense Regulation 18-B was enacted, allowing known Fascists to be imprisoned without trial. On May 30th, 1940, Taylour was arrested at her home, and interned at Holloway Women’s Prison in London, along with the Diana Mitford – over 1000 British citizens were so imprisoned. She was later sent to Port Erin prison on the Isle of Man, and in her recently released MI5 file, her prison warden described her as “one of the worst pro-Nazis in Port Erin…she is in the habit of hoarding pictures of Hitler and had in her possession a hymn in which his name was substituted for God’s.” After 3 years of imprisonment, Taylour was exiled to Ireland in 1943, as she held Irish citizenship – that country was officially neutral during WW2 – but remained under scrutiny by British security services until 1976, as she became a conspiracy theorist, and carried on agitating for extremist ideologies and groups for the rest of her life.

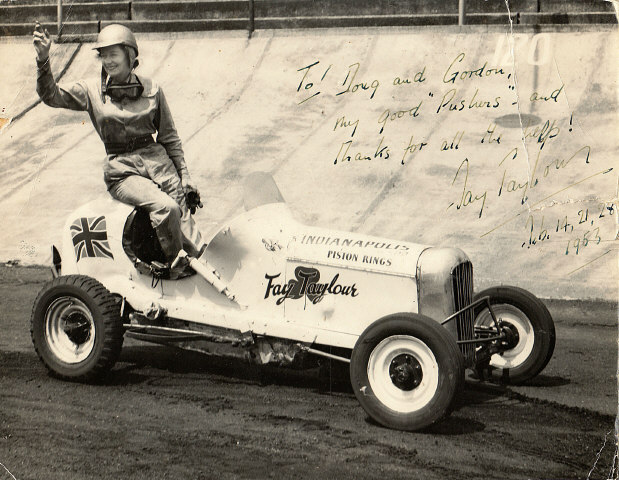

After the War, with her reputation soured in Britain, she emigrated to the US and took up midget car racing, and selling British cars in Lost Angeles. After a visit back to London in 1952, she was barred from returning to the United States due to her political history. She took up auto racing in Britain, and traveled to race in Ireland, Sweden, and Australia, and was the only pre-War female auto racer to take the wheel competitively post-War. She was allowed to return to the USA in 1953, and raced cars for another year, before giving up racing for good in 1954. She remained in the US until 1971, attempting without success to publish her memoirs and have a film made of her life, and worked odd jobs. She returned to Britain in 1972, and compiled her autobiography, which was never published (she rightly blamed her politics), but her collected notes did form the basis of Brian Belton’s flawed book (it devotes barely one paragraph to her politics, and her auto racing) ‘Fay Taylour Queen of Speedway’, published in 2006, long after her 1983 death. A far more comprehensive biography is Stephen Michael Cullins’ 2015 dissertation, ‘Fanatical Fay Taylour; Her Sporting and Political Life at Speed, 1904-1983’.

Taylour’s story is fascinating, and tragic. Her 4-year motorcycle racing career shone brightly enough to earn her a permanent place in the motorsports Pantheon, but the ugliness of her political views changed her reputation from glorious to notorious.

A glimpse into her character can be gleaned from an Australian newspaper interview in 1930, on the conclusion of her final world dirt-track tour: “When, three years ago, I got my first motorbike, I was told I should break my neck. But I didn’t! In fact, I entered for the Southern Scots Scramble at Camberley in that same year. It was a grueling test for both machine and rider, but more especially for the rider. Much against his will, and after a great deal of persuasion, an uncle had financed me for this event. I had sworn to win it! He didn’t believe it possible. But, I felt it was, because I wanted it to be the means of making a new career. So I kept on saying to myself: ‘Girl, you must win!’ And win I did! From that date my career as a racing motorcyclist began.

“I wanted speed. I had won a score or so of cups, but you can’t live on cups! When, in the early part of last year, I saw the dirt-track speeding, I made up my mind to go in for these new thrills. I was refused admission to three speedway tracks, one after the other. Then, whilst the officials were in the Isle of Man last year for the T.T. races, I took advantage of their absence to test myself on the dirt track at Crystal Palace. The result was that, by the time they returned, I was able to show them efficiency in the new sport. I was established, and, as is generally known, I made the most of my opportunities there during the summer of last year. Even a woman can get what she wants, when her want is strong enough.”

Related Posts

July 8, 2017

The Vintagent Trailers: Mancini, The Motorcycle Wizard

The mechanic that helped debut five of…

while i certainly find her unrepentant Nazism repugnant(and frankly not understandable) i cannot help but wonder if she would be so relegated to the ash bin(dust bin?) of history if she were a Communist,of which there were also many in Britain

It’s a fair question, and of course, if politics change, and far-right movements in the US and Europe take power, Fay may again be lauded as a hero. It’s the ‘losers’ who become repugnant, and historical figures with far larger death tolls than Hitler (eg, Stalin and Mao) are not vilified in the same way, because they remained in power, and won their wars. Their ideologies weren’t racist, though, and that’s a big difference between National Socialism and Soviet or Chinese State Socialism.

Sadly, as mentioned in the article, Fay Taylour is an ‘impossible figure’ to laud, because of her vocal politics the last 44 years of her life. History is written by writers, and while Geoffrey Belton wrote a ‘pre-Fascist’ life history of Fay, anyone looking at her whole story will likely conclude with ‘yuck’, and pass her by. The ‘dustbin of history’ is actually a lack of interest by writers to tell her story. The point of this article was to explore why Fay Taylour has nearly vanished, except as an oddity in photographs, shared without attribution or explanation.

yep! in judging Fay(and who would argue she deserves it) we tend to forget Henry Ford and Charles Lindbergh admired Hitler-at least for awhile; i have a friend whose father flew for the Luftwaffe and he and i agree that Hitler might well have won had he not put the best and brightest in the gas chambers-not that that would have been a good outcome! Russia and Poland both had much longer histories of anti-Semitism (a misnomer as Arabs are also Semitic) with Germany it was more sporadic,nor was it confined to Germany,Russia and Poland-the UK(as noted)France and Spain had their own versions;it may broadly be said to have included all of Europe at one time or another;an amazing people the Jews,able to triumph in the face of adversity time and time again;in the Depression era National Socialism was as pernicious as the supposed opposite number Socialism and Communism-people were desperate for a fix to the economic problems of the world-luckily one could go to the motorcycle races!

We remember what people are willing to die for. As such, she is remembered.

Mr. Eckart, Fay Taylour was not willing to die for her beliefs, as keyboard fascists like you would believe. She was more than willing to support a demented racist who killed millions of innocent people, and caused the death of tens of millions in his megalomaiac war. What a time we live in, with fascist scum like you peeping from the shadows, feeling safe during the brief presidency of a blatant white supremacist. This, too, shall pass.