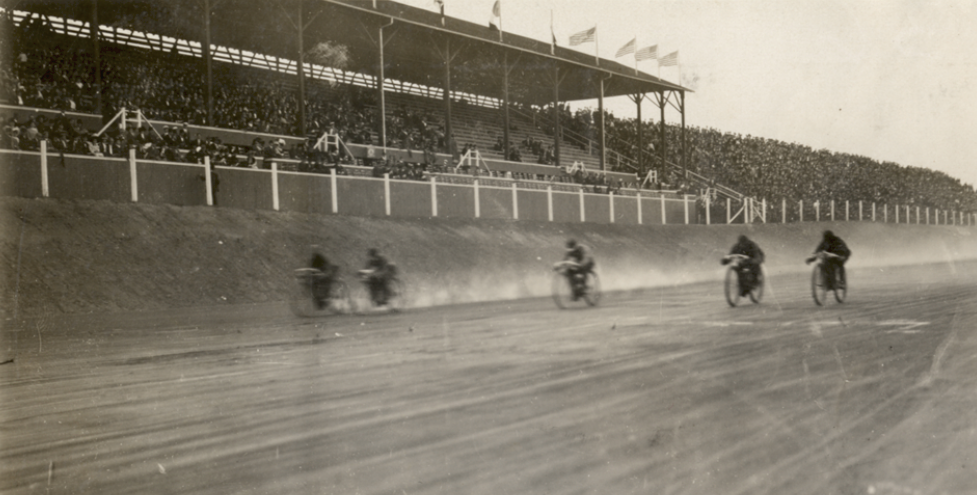

Beginning in the mid-Teens, factory racing teams from Indian, Harley-Davidson, and Excelsior fought a hard battle for dominance on the board- and dirt-tracks around the country. Great riders like Gene Walker, Shrimp Burns, Otto Walker, and many others made their names riding for either the Indian ‘Wigwam’ or the Harley ‘Wrecking Crew’. The bikes they rode were little more than bicycles, with powerful V twin engines, and no brakes. Motorcycle racing was a major spectator sport and drew tens of thousands of spectators across the country.[Words: David Morrill]

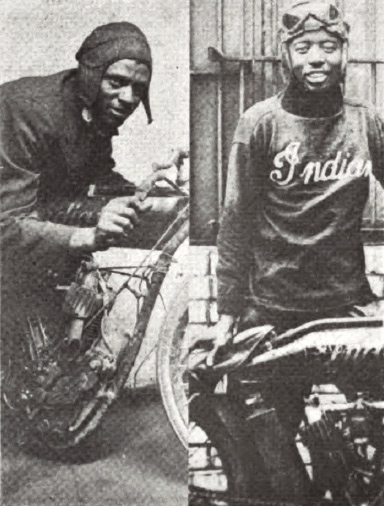

with their Indian Racers – Atlanta 1924

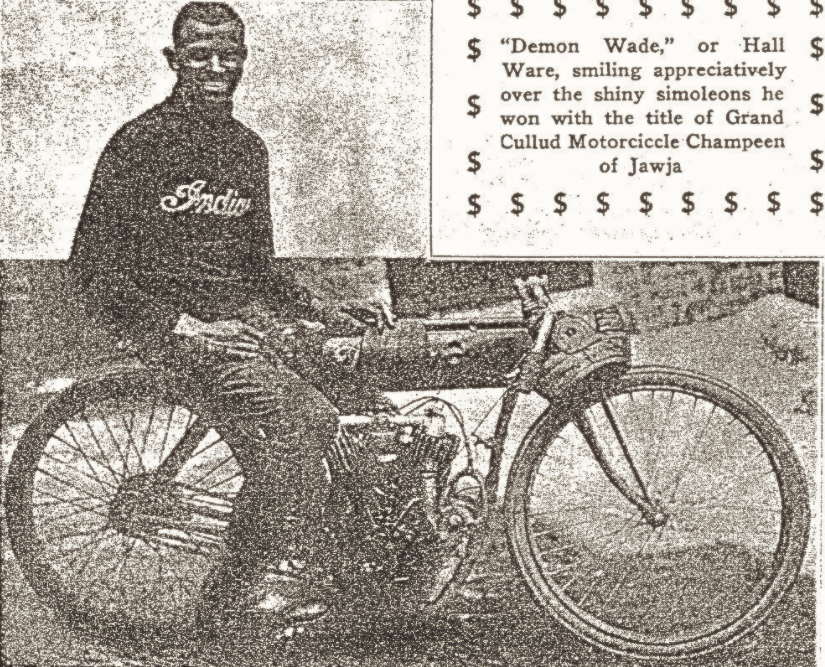

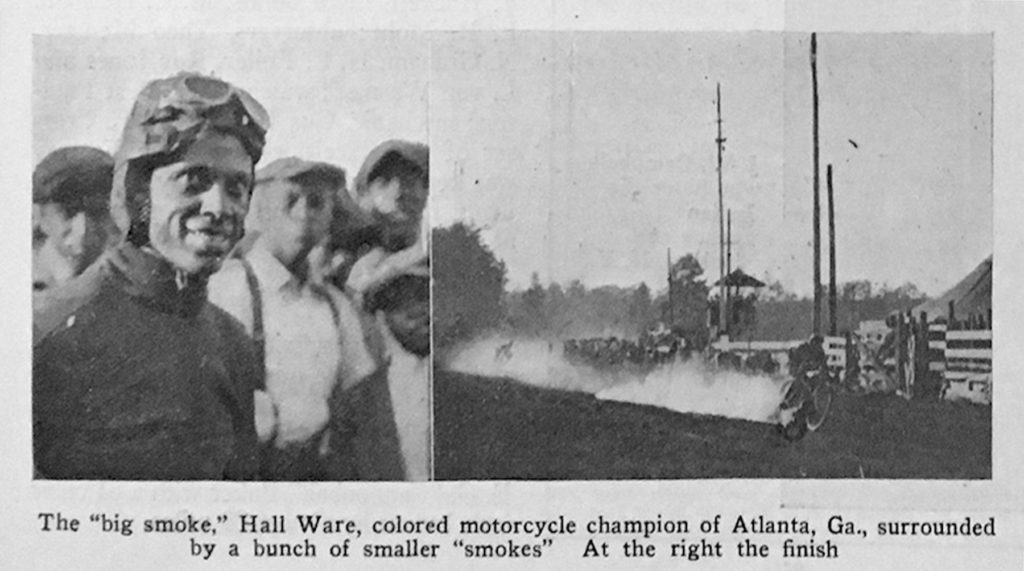

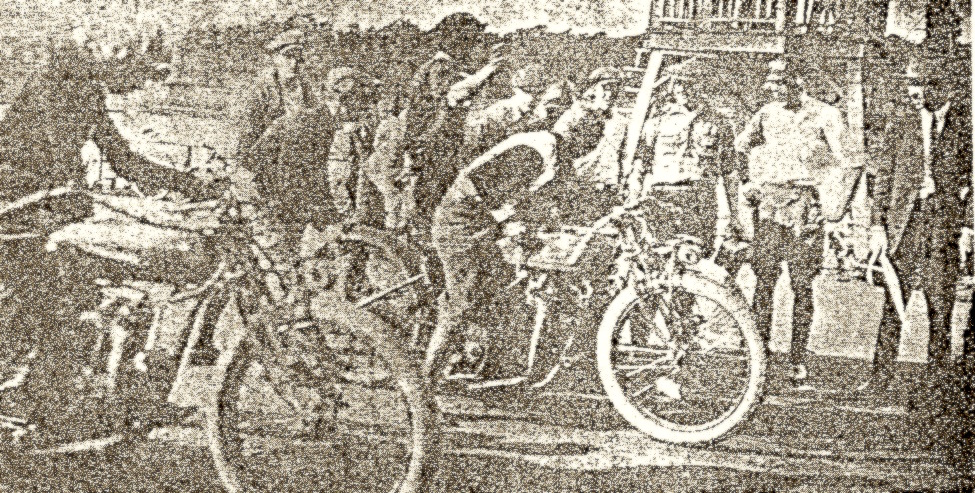

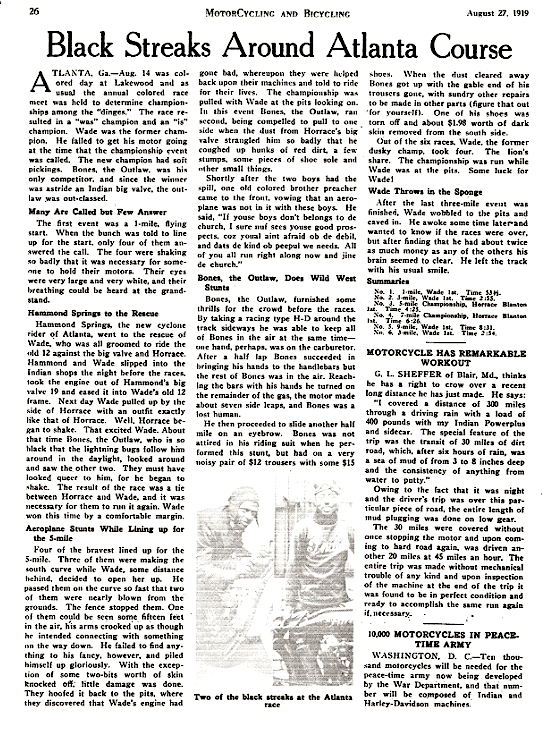

In Atlanta, another group of racers sought fame and fortune, whose story today is virtually unknown; these black riders had colorful nicknames like Hall “Demon Wade” Ware, Horace “Midnight” Blanton, and “Bones the Outlaw,” who raced each other at Atlanta’s Lakewood Speedway from 1913 to 1924. They didn’t have the latest factory racing bikes, and their racers were often cobbled together with obsolete parts from the scrap piles of local Harley and Indian dealers. They were known as Atlanta’s ‘Black Streaks’ and while their races were covered by the national motorcycle press, the articles reflected the racial prejudice of the day, such as a 1919 Motorcycling and Bicycling article titled “When Dinge Met Dinge in Georgia”; the text was even worse.

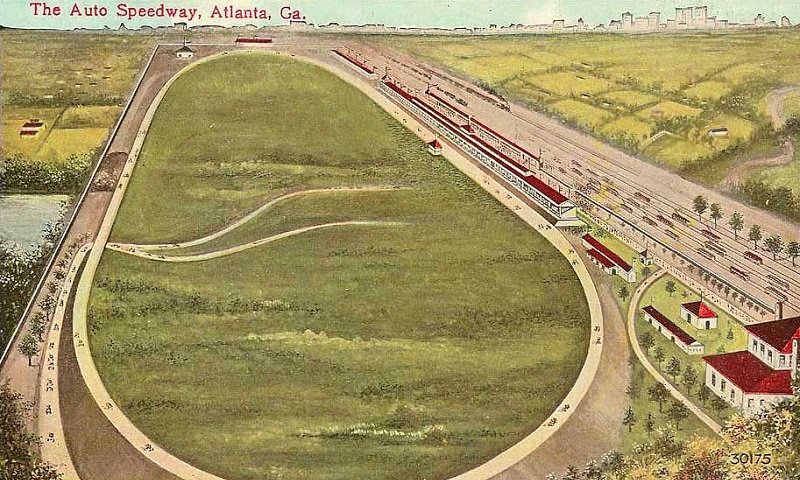

In 1909, Coca Cola founder Asa Candler opened the Atlanta Speedway on what is now the site of Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport. The two-mile oval track featured an asphalt and gravel racing surface, which was modeled after the recently opened Indianapolis Speedway. Motorcycle races (for white riders) were held there beginning in November 1909. The first mention of a motorcycle race for black riders appeared in an Atlanta Constitution article concerning events held at the Speedway on Labor Day, 1913, by the ” Atlanta Colored Labor Day Association.” The race featured a black automobile racer, “Hard Luck” Bill Jones, who had recently switched to racing motorcycles. The race results appeared in a later Constitution article on Jones; John Sims on an Indian was the winner.

The article quoted local Atlanta Harley-Davidson dealer Gus Castle, and Thor/Jefferson dealer Johnny Aiken. Both dealers’ statements reflected the attitude of most whites in Jim Crow Atlanta. Gus Castle stated: “I think the negro racing game is a substantial benefit, as it drives the last nail in the coffin of motorcycle track racing in Atlanta, and that’s a blessing of no small importance.” Aiken’s stated: “Except that it will popularize motorcycling among Negros and in that way cheapen the sport in the eyes of white men.” The article went on to state that there were about forty black motorcyclists in Atlanta, and that the white dealers refused to sell them new motorcycles. After reading the article in Motorcycling, Federation of American Motorcyclists (F.A.M.) Chairman John L. Donovan wired the track operators stating the Atlanta Motordrome would be “outlawed” and their race sanctions withdrawn “as the F.A.M. does not allow colored men as members.” Despite the threats from Donovan, on October 19, 1913, an article appeared in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper announcing a race featuring black riders would take place at the Motordrome.

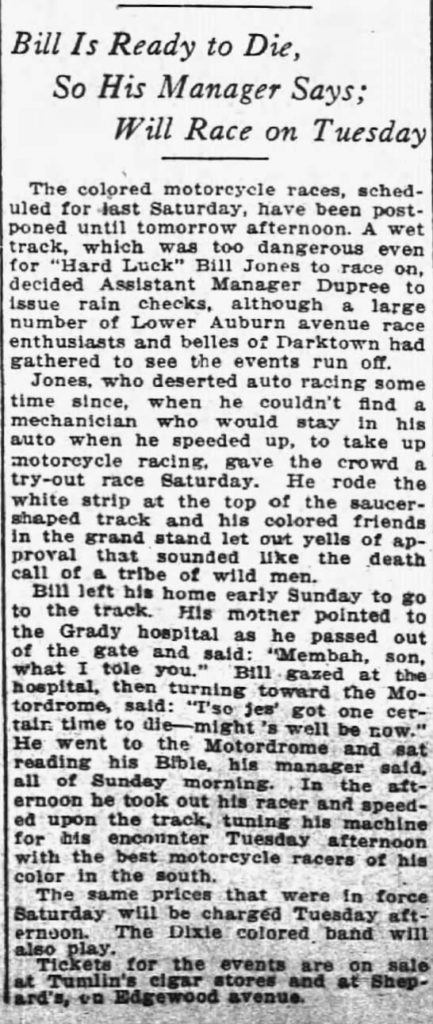

The article states “The men who ride are all experienced and have ridden motorcycles on board tracks before” (that statement seems to confirm that black riders rode on Motordrome-style board tracks in other cities, but sadly, that history has been lost). The Atlanta race was postponed twice due to rain. Weather was a constant problem at the Atlanta Motordrome – the riders could not safely race on the steep wooden banking when it was wet, and races were often postponed several times. The race featuring black riders took place at the Motordrome on afternoon of October 28, 1913, and featured black riders Bill Jones, and Lloyd Brown of Atlanta, along with the Wilson brothers from New Orleans, and Ben Griggs and Willie McCabe of Chattanooga. The Atlanta Constitution did not cover the race, and the results are unknown. Less than a month after the race, an article appeared in Motorcycling World and Bicycling Review that stated the owners of the Motordrome had filed for bankruptcy. It further stated: “This Motordrome earned an unsavory reputation by pulling off a race with negro riders, in defiance of F.A.M. regulations, thereby becoming outlawed as long as the present management exists.” The Motordrome reopened the following year under new management. There is no record of any further races featuring black riders at the track. With the opening of the Lakewood Speedway, motorcycle racing shifted away from the Motordrome.

The Lakewood Speedway, one-mile dirt oval, opened south of the city in 1917, and immediately began running motorcycle and auto races. The track owners revived the racing series for black riders, which they billed as the Grand Colored Motorcycle Championship Race. A black South Carolina racer named Tom Reese, who called himself the ‘Champion of South Carolina’, arrived in Atlanta for the June race. Reese’s manager began to brag that Reese could ‘beat any Atlanta rider,’ and he was prepared to place a large cash wager to back up his claim. The event drew large crowds from Atlanta’s black community, and bets were placed on the favorite riders. While the Harley-Davidson, Indian, and Excelsior factories had no involvement in these races, the local Harley-Davidson and Indian dealers gave limited assistance to their chosen racers. They also often placed large wagers between themselves on the outcome of the race.

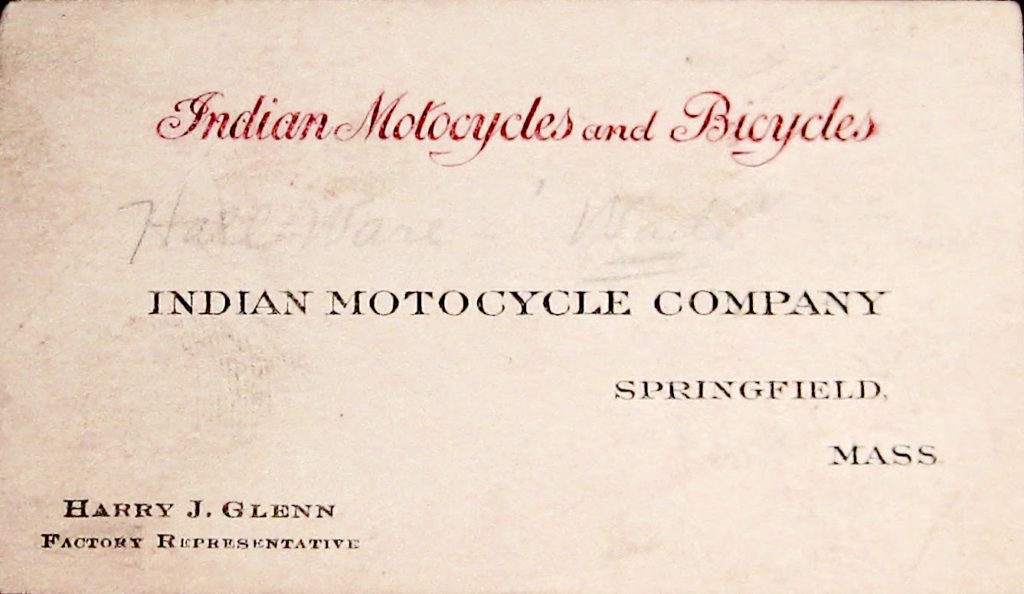

On May 31, 1919, ‘Bones the Outlaw’ appeared in a photograph (was standing with his employer Harry Glenn) within a pre-race article for the 1919 Southern Dirt Track Championship, which featured top white riders from around the south, including Birmingham’s Gene Walker , and Atlanta’s Nemo Lancaster. At the local Indian dealer, Hall ‘Demon Wade’ Ware saw an opportunity; already an accomplished local racer, Ware worked for the dealer as a mechanic. He convinced his boss, Nemo Lancaster, to lend him a competitive bike to race against Tom Reese. While Lancaster recognized Ware’s talent, the rumor was he had a very large side bet with Reese’s manager. At the start of the race, Reese on a Harley-Davidson jumped out to an early lead, and Reese’s manager expected to win the wager. Ware, on the loaned Indian, soon caught the Carolina Champion and passed him, winning the race. Ware claimed the $150 first prize, and Lancaster collected on large side bet with Reese’s manager.

The race in August 1919 was another hard-fought battle between ‘Demon Wade’ and ‘Bones the Outlaw’. ‘Midnight’ Blanton won several of the preliminary races, and had a shot at winning the championship race. But the night before the race, Atlanta board track racer Hammond Springs (who was white) helped Wade install Springs’ new Indian racing engine into Wade’s older Indian frame. The competitive engine allowed Wade the edge he needed to leave Blanton in his dust. On the final lap, he and Bones the Outlaw, crossed the line in a tie. This required a rematch, which Wade won hands down, claiming the 1919 championship.

The race held on June 5, 1922, proved to be a bit of a disappointment. Once again several racers from around the South arrived, prepared to race. When Hall Wade’s bike was unloaded, the motor was covered. This gave rise to rumors that Wade had another special racing engine, which was a reasonable supposition, as Wade was close to his former employer, Harry Glenn – by then an Indian factory representative. When race time rolled around, only Horace Blanton came to the starting line to face Wade. Wade won two five-mile races, defending the Southern Champion title he’d held since 1915. The remainder of the the day’s races were canceled due to the lack of competition. By the 1924 race, ‘Bones the Outlaw’ had switched to racing automobiles, and ‘Demon Ware’ had sold his machine and moved north. For the 1924 races, ‘Bones the Outlaw’ made a demonstration run in his racing car, blasting around the dirt oval and putting on quite a show, narrowly avoiding a crash several times. In the motorcycle race, Horace Blanton had no real competition, his two chief rivals having moved on, and he easily claimed the Championship over a field of less experienced riders.

Good article. Nice discovery

Very interesting article. Will have to check out Mr.Wrights publications.

Great piece of motorcycling history that few have ever known about. Great work David.

– Don Emde

Really good.Thanks!

Somer

Wow.. Great history here! Thanks for posting..

If they suffered as much abuse as Major Taylor did while bicycle racing in America, they must of had some incredible tales to tell. Can’t believe I never heard of this until now; thanks for sharing.

For anyone who hasn’t heard the Marshall ‘Major’ Taylor story; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marshall_Taylor

A champion bicycle racer, who broke the ‘color barrier’ in the US decades before Jackie Robinson…

Paul-I have a friend who has a photo of a young black guy on a board track racer. This picture came from the REVEREND Stuart MUNGER–I will try to get a copy to post –It is a great photo.

The Harley dealer in Atlanta in those days was Cunningham Harley Davidson-I wound up with a 2 cam FH race engine that came from that dealership. Cunningham sponsored quite a few racers in the earley days.

RL Jones

Anonymous said…

@R.l., I’d like to see that photo. There wasn’t a lot of information on these guys. Just a few annual articles on the championship race. For the most part, the included photos did not indentify the racers. I would like to find out more about these guys. If I can get the article up in the Atlanta area, someone might recognize a relative.

– David Morrill

Great bit of history. Would be nice to find out more, although I expect all the racers are now long gone and there wasn’t much written down about their experiences

publication, or what families have albums of ‘great uncle Horace’ on a board track Indian.

Getting the word out will help the story to surface, much as the ‘Black Chrome’ exhibit in LA brought out the story of the Easy Rider bikes; it took several years, but eventually, the story emerged, and photographs, and supporting evidence from people who were there. Easier for the late 60s than the 1920s, true, but I reckon something is out there.

I have further questions too…about the track owners who snubbed ‘no black’ FAM (precursor to the AMA) rules to have races with black riders. Clearly, there were enough black motorcyclists to support racing, and enough fans to see them and justify the track time. I have a feeling this wasn’t just a ‘circus’.

HEY – Thanks for the great story –We looked at this picture for years and wondered where this guy was racing.

I know a little about the track in Atlanta. My good friend Bobby Pearce told me many stories about the Lakewood track. Her husband Clarence Pearce raced at this track in the old days. Mrs. Pearce was quite the motorcycle rider herself, and had asked Clarence if she could take his bike around the track one time. Clarence [Harley Rider] said certainly not -it was against the rules for women to be on the track–So Bobby-being the special gal she was, convinced one of Clarence’s friends [INDIAN RIDER}to let her make a lap around the track to teach her husband a lesson. So she stuffed her hair up under a leather cap and proceeded to pilot this Indian around the track–After a few laps she had started to lap some of the slower riders, and run with some of the “Hot Shots”. When she finally pulled in the pits -there was quite an uproar about who this new rider was –Well soon it was found out that there had been a lady on the track.

The judges came down to Clarence and said this was absolutely against the rules and they suspended Clarence from the race for this infraction.She was a great lady and taught me quite a bit about the early days of racing in the south.

I will post a picture of her when I finished bringing her husband’s hillclimber back to life –we rolled it out -and there was a little tear in her eye and then she just threw her leg over the seat and said well let’s hear it run–Dedicated to my good friend “BOBBY PEARCE”

One reason most people don’t know much about black people racing motorcycles are that blacks were not allowed to race in the AMA. As in other sports, baseball especially, blacks were prohibited from the sport and had to go form their own venues, organizations etc. Go find an old AMA rule book from the 20s and 30s and not only were blacks not allowed to be AMA members, it was the very first rule in the book. Rule #1: members must be white. No slam to the current organization, but “back in the day,” that’s how it was.

– Don Emde

I was sitting on the hillside at Barber Motorsports last weekend watching the Superbike races. There were several African American fathers in my area, who brought their sons to watch the races. I hope thet will learn that their racing history runs back to the early days of the sport! These guys laid the foundation for Bubba Stewart and many others.

I hope I can find some relatives of the few guys mentioned, and find out more about them. I learned lots more about Gene Walker from his relatives, after that article went up. These guys are the earliest black racers I’ve found. R.L. told me about a group of black flat trackers in the 50s. I don’t remember any black club or AMA Pro roadracers from my days in the 70s/80s, but I only raced in the south. You had a much longer career and raced across the country and overseas.

-David Morrill

I have some information you might like about early B’ham Harley shops.

Lee ‘Onion’ George

aredandgold at msn dot com

Don’t ask me why, but one thing I collect are old AMA and other rule books, so I have a lot of them and somewhere in the 60s I think it was the rule disappeared. I guess that matches to the days of JFK and Lyndon Johnson and the changes in America at the time.

The early AMA leadership were masters of controlling their messages. Not only were blacks “non-existent,” but if you see a story about races in those days, they would list Harleys and Indians, but the guys who rode Nortons, there was just a blank line shown for their motorcycle.

– Don Emde

Thanks for posting this. One of the coolest things I’ve read in a long time. Hopefully more info and photos come to light.