Before the advent of special effects teams using models or double-exposures to mimic dangerous action, a surprising number of silent film actors performed their own stunts ‘in-camera’ – meaning the events were totally real, although very carefully planned. The premier example of the actor/stuntman was Buster Keaton, who can be seen riding a motorcycle from the handlebars, riding through fences, and making dangerous jumps across moving trucks between gaps in a bridge. It’s still great stuff!

Keaton is widely considered the best physical comedian of the silent era, thinking up and executing his own elaborate stunts, and directing himself in wildly popular films during the 1920s. His po-faced expression, which subtly morphs from maudlin to curious to shocked, was a key to his comedy, being a total contrast with the outrageous antics in his films. Keaton included elaborate stunt riding on a 1923 Harley-Davidson ‘J’ model in the 1924 film ‘Sherlock Jr,’ which can be seen above. Another scene in ‘Sherlock’, featuring a moving train and water tower, actually fractured his neck vertebrae – but Keaton didn’t realize it until he was x-rayed years later. He had an exceedingly long movie career, successfully making the transition to ‘talkies’ and then into television. His last film appearance was ‘A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum’ (1966), when he was 70 years old.

Larry Semon was another talented actor/director/stunt man, who’s nearly forgotten these days, but in the 1920s he was a very successful and wealthy film producer. He directed the first, silent version of the ‘Wizard of Oz’ in 1925 (in which he played the Scarecrow), and worked with both Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, before they created their immortal comedy team. Semon directed and acted in the short ‘two reel’ film ‘Kid Speed’, about two auto racers (Semon and Hardy) competing for the same girl (‘Lou duPoise’, a reference to the duPont family). Semon was known for his elaborate/expensive sets, sometimes building fully functional houses for a film, as well as huge gags – in the case of ‘Kid Speed’, an entire mountainside slumps onto a road for comic effect. If you want to skip the slapstick and see the cool old racers, jump to the 14-minute mark.

‘Kid Speed’ is a two-reel film, shortened to 18 minutes; this may be the result of deterioration of the original, highly volatile nitrocellulose film stock. Semon died in 1928 of tuberculosis, and many of his films languished in private collections before being rescued and transferred to more stable ‘Safety Film’ stock – cellulose acetate, which is much less flammable. Note the words ‘Safety Film’ on your old 35mm Kodak negatives; previously they would have had ‘Nitrate’ in dark letters printed. Nitrocellulose is explosive, derived from ‘guncotton’ and related to smokeless gun powder, and was the foundation of the DuPont chemical fortune.

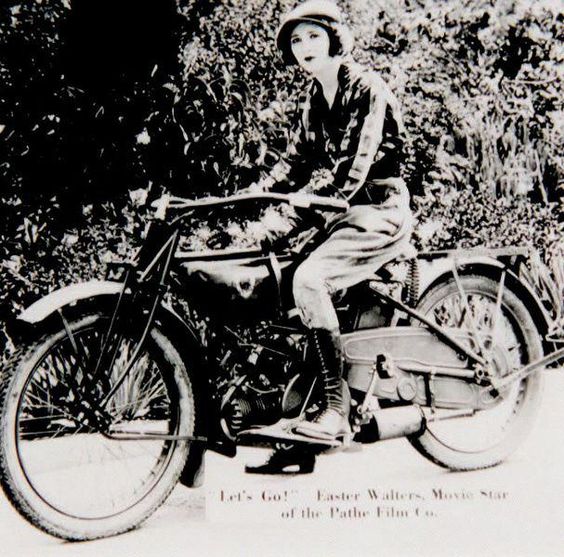

Some of the best motorcycle stunt riding in silent films was done by Easter Walters. She’s the real star of this one-reel short ‘Taken For a Ride’, in which a Larry Seamon lookalike (‘Bobby Emmett’ – Robert Emmet Tansey) tries to impress a girl by stealing a 1922 Henderson DeLuxe with sidecar, with predictable results – his girlfriend knows more about the workings of a bike than her suitor. This short is a ‘one reel’ movie, ie the length of a spool of film; 12 minutes, and Walters is clearly capable of handling a motorcycle with verve. The publicity photos of her ‘surfing’ a 1919 Harley-Davidson Sport Twin are priceless!

Easter Walters is barely remembered today, but was born in 1894 in Iowa, and moved to Hollywood around 1918. She made some headway as an actress in the silent films ‘Common Clay’ (1919), ‘Hands Up!’ (1918) and ‘The Tiger’s Trail’ (1919). She was known for performing her own stunts, and was a fixture of Hollywood gossip sheets in the ‘Teens for riding around town on her motorcycles – perhaps the Indian Model O pictured, and/or the Harley-Davidson Model J in other photos. ‘Moving Picture World’ in April 1919 ran an article titled ‘Breaking the Speed Laws is Sport for Easter Walters’. Sometime after 1920 she left the film industry; her final film was ‘The Devil’s Riddle’ (1920), and she was married that year to Harry Kinch. She remained in Southern California the rest of her life, and died in San Diego in 1987.

Harold Lloyd was an actor/director on par with Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, and more financially successful than either. He kept control over his image and his films, refusing in later years to allow distribution of his work unless for a very high fee…which meant that by the 1950s and 60s, his work was slowly forgotten, unlike his rivals. In common with other directors of the 1920s, Lloyd found that motorcycles added to the kinetic appeal of a chase sequence. The three-cop pursuit of Lloyd – riding two Harley ‘J’s and a Henderson 4 – in the 1920 film ‘Get Out and Get Under’, is a zany early car chase sequence.

Competition between directors for public attention meant increasingly treacherous stunts, and stuntmen were often injured or killed in the era – it was all part of the job description, just as Board Track racers could expect a short career, and considered themselves lucky if they escaped without serious injury. Buster Keaton demonstrated how far stuntmen would go for a laugh in the ’20s, while others did spectacular work as well. The following British Pathe film features stuntman Fred Osborne attempting a 25′ leap over a cliff on a Henderson 4-cylinder, using a parachute to soften his landing. The parachute essentially fails to open, but Osborne amazingly survived the fall. It was a ridiculously dangerous stunt, and undoubtedly done for self-promotion, in the manner of Evel Knievel decades later. The Silent Types were a strong bunch.