American Honda’s lightbulb moment to launch the CL 72 was a record run over the wide-open desert of Baja, Mexico. While plenty of SoCal racing took place in California’s Mojave desert, very little happened south of Tijuana, and an audacious 1000-mile endurance test could be conducted out of the public eye. Legendary desert racer Bud Ekins was tapped, but his contract with Triumph meant Honda was a no-go, so he passed the opportunity to his equally talented younger brother Dave, who teamed with LA Honda dealer Bill Robertson Jr. No official record existed on the run from Tijuana to La Paz, so the bikes only needed to finish the 963-mile ride, and send telegrams from each end to confirm their time. That didn’t mean the prospect was easy; with no gas stations from Ensenada to La Paz (851 miles), and few villages, the riders would need to be supplied en route. The going had only a few miles of pavement, and long stretches were untracked sand through desert wilderness.

The riders’ route was scouted by air, then food, gasoline, and support were provided the same way. John McLaughlin, former Catalina GP winner (on Velocettes) piloted a Cessna 160 with Cycle World founder Joe Parkhurst and photographer Don Miller as passengers. A larger Cessna 140, piloted by Walt Fulton, carried the food and fuel for the riders, along with Bill Robertson Sr. The bikes needed 9 refills, and landable spots were chosen for riders to meet the planes. Come ride day, Ekins and Robertson sent their telegrams from Tijuana at midnight, and headed south on Highway 1. There were hardships and lots of crashes; they got strung up on barbed wire fences while sun-blinded, Ekins fell 13 times in one night, and they were lost and rode in circles for 6 hours. Robertson’s Honda holed a piston 130 miles from La Paz after crushing his air cleaner in a crash, and grit entered the motor, but he carried on with one cylinder, catching up to Ekins 2 hours after he’d clocked a 39hour, 49minute elapsed time. The point had been proven, and the publicity for Honda was certainly worthwhile, as they sold 89,000 CL 72s from 1962-68.

Not long after Honda’s ride, Bruce Meyers took his prototype Meyers Manx VW dune buggy along the same route, and lopped 5 hours off Ekins’ time – those hours spent lost at night no doubt. Thus was born a car/bike rivalry, which sparked the idea for a proper race, and Ed Pearlman founded the National Off-Road Racing Association (NORRA), which ran the first Mexican 1000 race in 1967. Motorcycles, cars, and trucks ran the same route, using a rally format, with mandatory checkpoints in the multi-day event. The Mexican 1000 was run for 6 years, before the Oil Crisis of ‘73 dampened everyone’s spirits; NORRA was disbanded, and there was no race that year. But nobody had asked Mexico’s opinion on the matter; the attention focused on the nearly vacant Baja peninsula was too good to let lapse, so they promptly announced their own Baja 1000 race over the same course. They contracted Mickey Thompson of Southern California Off-Road Enterprises (SCORE) for organization, who hired Sal Fish (of Hot Rod magazine) to created SCORE International to organize the Baja 1000, which it has done since 1974.

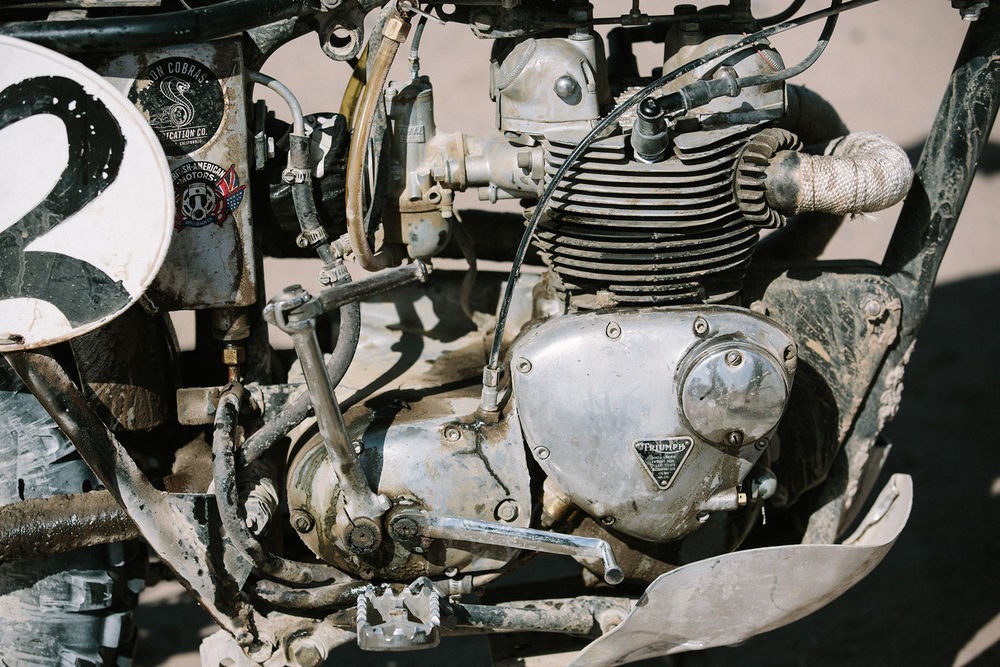

The rising interest in vintage dirt racing in recent years spurred Ed Pearlman’s son Mike to revive NORRA, and bring back the original Mexican 1000, with its multi-day rally format. Started in 2009, the race originally catered to pre-1998 motorcycles, cars, and trucks; now there are classes for modern vehicles as well, in case your 800hp trophy truck needs exercise between professional Baja bashes. Running superfast modern desert tools alongside vintage motorcycles and cars is daunting, but also part of the fun, at least according to Julian Heppekausen. He recently rode his 1966 Triumph T120 desert sled, ‘Terry’, to victory in the Vintage Triumph Thumper class, becoming the first rider ever to win, and one of only 3 to complete a 1000-mile Baja race on a Triumph.

You might know Julian Heppekausen as CEO of the Deus store in Venice, CA, or for his exploits on Terry the Triumph in the Barstow-Las Vegas off-road race, which he’s finished 4 times. He credits this success to the quality of Terry’s original construction by motorcycle industry icon Terry Prat, for whom the bike is named. Prat was the European MX correspondent for several magazines in the 1970s, then a manager at Cycle News from 1979 – 2011. The ’66 Triumph T120 desert sled was his last build, which he raced in the Barstow-Las Vegas Rally in 2011 (it’s not a race; that’s not allowed in the tortoise sanctuary – but everyone knows who finished first). Heppekausen bought the bike in 2012, and carried on competing across the Mojave desert every year since, finishing the ‘hard’ route twice. The means riding with new KTMs and Honda 450s, and his Triumph is the only 1960s bike to finish the Rally in a very long time. “They really don’t have a class for such an old bike – they call 1980s twin-shock motocrossers vintage!’

Keeping a 50-year old Triumph from grenading mid-desert exposes Heppekausen as a sensitive hooligan; “You need to know your bike really well. There’s a harmonic hum at certain rpms, where it seems like the motor will go forever, and in a long race you have to bring it back to that pace when you can. I continually pat the tank and thank Terry for not breaking!” Some vintage riders are scared of breakdowns on gentle street rides, but the old saw ‘the more you ride them, the better they get’ seems to apply here. Julian shipped Terry the Triumph to Europe in 2014, competing at events in Germany and England; it’s also been filmed wheelying in front of the Eiffel Tower under Dimitri Coste. After successes in Vegas-Barstow, he decided to try the revived NORRA Mexican 1000, along with several friends on their own vintage Triumph dirt bikes, although Terry the Triumph was the only finisher.

That’s perfectly understandable – all the bikes were at least 50 years old, and 1000 miles of desert racing is insanely demanding. Julian notes, “Modern trophy trucks with special tube-frame chassis and high-HP motors run 36” of suspension; they can run over a basketball and not feel it. I can’t do that on a Triumph with 3” of travel, and when the road is full of rocks, I could hit a baseball and be thrown off. Near the end of the race was a 15-mile stretch of rocky downhill, which was mentally challenging after 1000 miles, especially with trophy trucks passing at 140mph! I have to go to work on Monday, so kept way left to preserve myself.” While running with $200k, 600hp specialized desert trucks is hairy scary, it has benefits too, “Robbie Gordon passed me around a corner, driving like I’ve never seen a car driven. I was doing 60mph, and he was doing 110mph – I don’t know how he got around! And I was the only one watching – it’s the best view of the race, from the saddle.”

While Julian races Terry the Triumph far and wide, it isn’t actually his machine; when purchased from Terry Prat, he immediately gifted the Triumph to his son Henry, as a legacy. Henry isn’t big enough to ride a Triumph yet, but he likes to remind his dad whose bike it is, “My wife and kids met me at the finish in La Paz, and Henry told me to clean the bike! I said let’s leave it dirty a little bit yet. Terry’s had some real adventures, including wheelies in front of the Eiffel Tower. The best people have worked on it, and it’s been in many hands, but you know, we build these bikes for ourselves, and they eventually end up with someone else. That’s why I gave it to Henry – for the future.” And the future will remember that Terry was the first Triumph to win (let alone finish) a 1000-mile Baja race, an epic accomplishment in any decade – our hearty congratulations to Julian Heppekausen and all who helped make his win possible.

[Originally published in Cycle World]

Related Posts

October 3, 2017

The Vintagent Selects: Falcon Kestrel – Desert Ride

In 2010, Falcon Motorcycles revealed…