1980 Vetter Mystery Ship

Craig Vetter had an outsize influence in motorcycling, beyond his personal fame or fortune, although he’s had plenty of both. While the motorcycles he designed for production were strictly limited-edition specials (including the 1973 Triumph X75 Hurricane – you’ll find that on our upcoming 1970s Design list!), his Windjammer fairing and hard bags were seemingly everywhere in the 1970s and ’80s, and pushed the OEM manufacturers to include streamlined wind protection on their production touring motorcycles.

1980 Target Design ED-1

1981 Honda Motocompo NCZ 50

Nevertheless, the design of the Motocompo is ingenous, and perhaps the only real inheritor of the ‘Motosacoche’ concept, being truly a ‘moto in(to) a suitcase’! The design is impeccably 1980s, with its flush, integrated head- and taillamps, retractable everything, and terrific graphics. Best of all, the City/Motocompo advertising campaign was launched with the British ska band Madness providing entertainment and music for the ad. It, too, is a highlight of 1980s design!

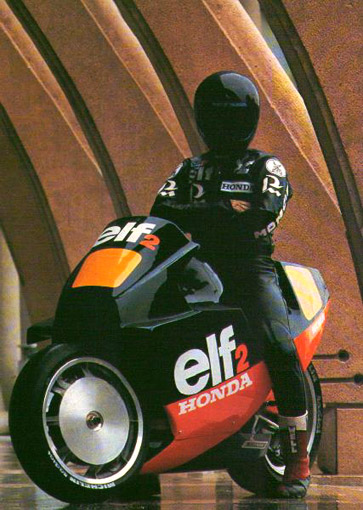

1981-6 Honda ELF racers

1984 Fantic Sprinter

1986 Colani Egli MRD-1

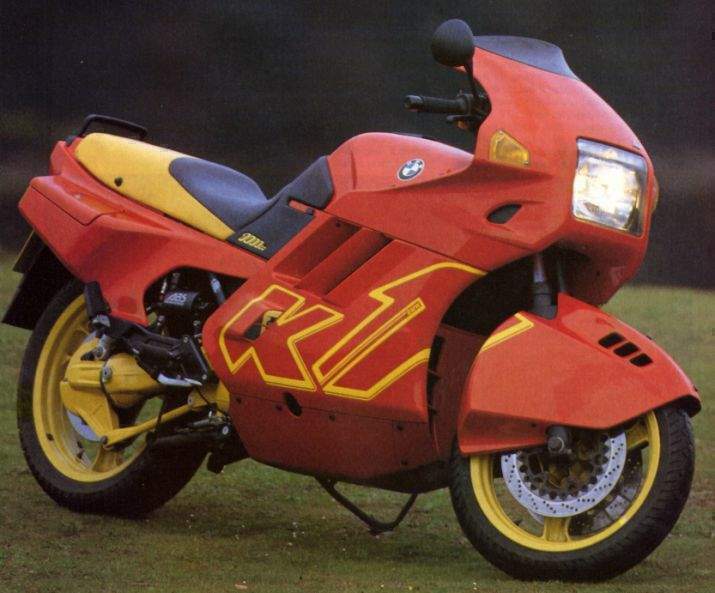

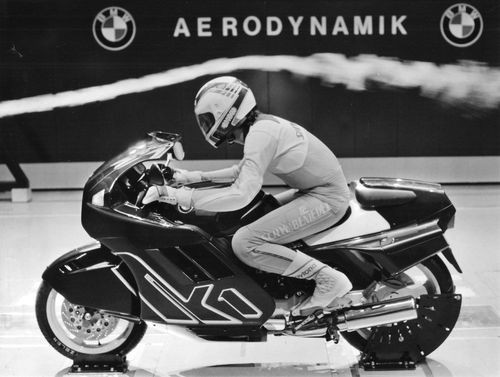

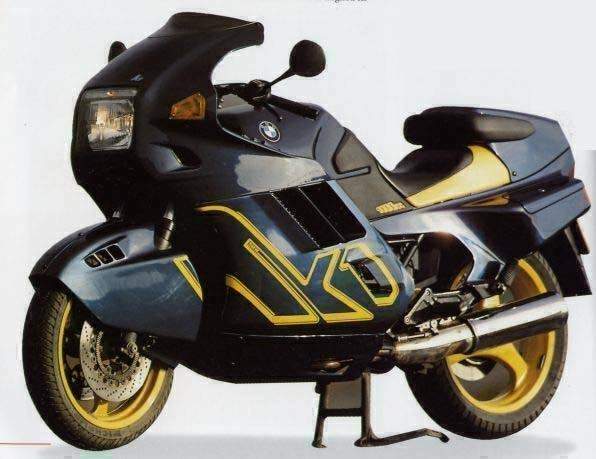

1988 BMW K-1

Paul,

EXCELLENT gathering of motorcycles in this story…….

I think some of what you see in 80’s products in general is an advance of industrial design. That scooter at the beginning of your story is not so much styled like a car as designed like an appliance. The Audi TT is said to be another example of ID taking over for styling; it’s got front to rear symmetry, could have been drawn with a circle template, no need for French curves. In my mind design usually, not always, infers that function was in mind, fit with our bodies, for example. Styling is all about looks, rarely function. For example, all cars could look/work like Checker cabs and we’d get to work in them just fine. But emotionally, and due to our egos, we need styling. Hence sport utilities have design cues not of pick-ups, but of Art Center/California stylists.

Eh, eh the Fantic look like made in Lego…and the MV is squarely a night mare. when you compare it with the gorgeous original one. The BMW K1 designed by a Coventry ‘s friend was quiet homogeneous , like the ELF.

It’s the plastic generation who don”t want to show his engine and transform any maintenance in a gynecological sport!

The Fantic Sprinter looks like a Giugiaro design and he was busy in that decade. Do you know if he is the designer?

I don’t! There’s little available info about his model, but I’ll keep looking, and hopefully do a road test!

You seem to have forgotten the Laverda RGS 1000. A beautiful and well engineered beast. And it is still beautiful. Not unlike a round case 750 Ducati. Which is not so beastly but is it ever gorgeous. I have had women just stop on the street and start ranting about how beautiful the Ducati is (750GT fire engine red). And then you start it up with straight through Conti’s.I have noticed that most men stay away from both bikes, they just don’t seem to know how to deal with them.

I haven’t forgotten the RGS – I owned one! I focussed more on the origins of ’80s style than the subsequent designs. The Ducati Paso, the Suzuki Katana, the Honda Hurricane, were all outgrowths of these ideas and prototypes. Also, the Ducati 750GT was indeed an epically beautiful machine, and I’ve owned several, and done long mileages on them (like a 6000 mile tour from San Francisco to Banff, Canada, and back via the Rockies and Grand Canyon), but the bevel-drive Ducatis didn’t influence later design, sadly. The Guigiaro 860GT and square-case 900ss are examples of a downgrade in design in my opinion…

I love how the Katana was so 1980s that it even had a pop-up headlight. Can you get more 1980s than that? Is it possible to put T-Tops on a motorcycle?

Not to be a nitpicker but the engineer for the ELF is André de Cortanze, not de Cortanza… And I am very disappointed (Gary Oldman disappointed) not to see the BFG here…

http://www.citroenet.org.uk/miscellaneous/bfg/bfg.htm

Awesome article. I remember seeing some of these bikes in my Dad’s motorcycle magazines.

The Fantic Sprinter photos made by me 🙂

I had double of the these super uniqe 80s shit.

One was sold one is still mine.

find for more

https://www.instagram.com/mopedmetal/

bests,

Cosmic Bunuel

So noted and credited! Many thanks for your photo!