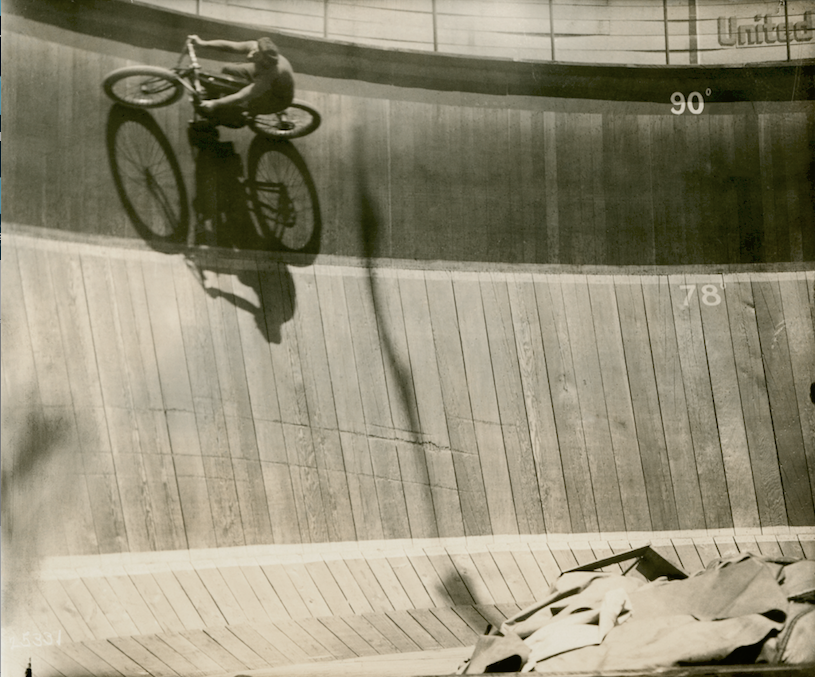

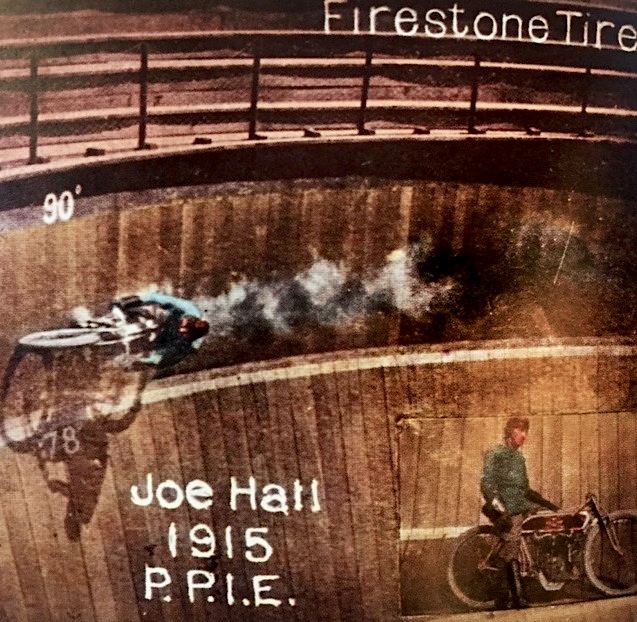

Grand Prix Racing and Wall of Death at San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition, 1915

In a rollicking, anything-goes city like San Francisco, it was still possible in 1915 to wow crowds by the hundreds of thousands with an old-fashioned spectacle. The City had emerged phoenix-like from the rubble of its tremendous shaking in 1906, and City fathers decided the 1913 completion of the Panama Canal was a good excuse for an Exposition to show off the newly rebuilt city. Mayor ‘Sunny’ Jim Rolph loved a party; he was a wealthy, debauched populist who owned two banks, a shipping line, and a whorehouse. He grasped the upside of not only building such an Expo, but also developing the land beneath it once the show was pulled down. The site chosen was the Harbor View area, a reclaimed marshland then hosting a tent city of ‘quake refugees, whose 635 acres were purchased for $1,036,440.78. Today it’s called the Marina district, and is both vulnerable to earthquake (being landfill) and very popular with SF’s burgeoning tech-yuppie influx.

A shimmering fantasy village – the ‘Jewel City’ – was erected in less than a year atop the former squatter’s camp, with dramatic, radical architecture at its core, a final flowering of 19th Century Beaux Arts beauty. The Panama Pacific International Exhibition (PPIE) was a carefully color-coordinated series of soft travertine pinks and ochres, its paths packed with the white sand from Monterey, which was fire-roasted to the right shade of brown. The heart of a central district of domes and towers was the Palace of Jewels, covered with 102,000 multicolored Czech cut-glass Novagems hung on wires and backed by mirrors, so they could swing and sparkle in the constant Bay breezes while illuminated by 50 arc lights. The nearby Rainbow Scintillator was a novelty, the first use of searchlights for entertainment, with a cadre of Marine Corps regulars manning 48 colored searchlamps in tight drill patterns, projected to the sky on clouds of steam (or frequently fog) from a stationary locomotive which had been painted to look like marble.

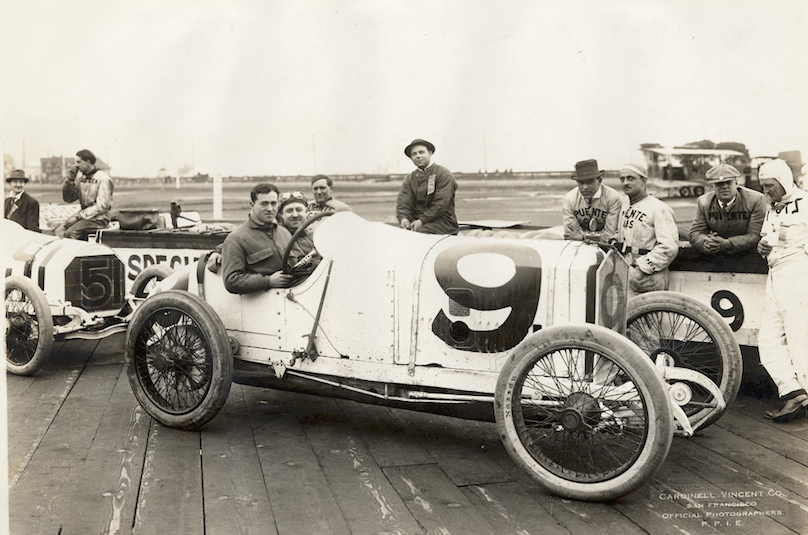

Amongst the dozens of spectacular grand halls, reflecting lakes and promenades were two racetracks; one for horses, the other for cars. It was intended from the start that the popular International Grand Prize and Vanderbilt Cup races would be held at the PPIE, and the course incorporated the roads of the Expo with an extension loop into the Presidio, atop undeveloped marshland (Crissy Field). Here the track was constructed from wood directly over the sodden earth, before it joined solid ground again within the Expo proper. Three grandstands were constructed for a total of $47,353, capable of seating 25,900 people, with the top seats 41’ above the track surface. The top of the grandstands were decorated with flags and bunting, and canvas awnings protected spectators from the rain. Athletic quarters were built under the stands, as were offices for the track officials, even living quarters for the athletic managers, nicely finished with plaster walls and steam heat. A 4-story judge’s stand stood at the start/finish line; with the top floor for judges, the 3rd floor the timers, and the 2nd for telegraph stations and journalists, all with open walls for an excellent view. Two score boards of 12’ x 30’ capped the roof, angled for a clear view for all spectators.

‘Baron’ Eddie Rickenbacker would become the most famous entrant in the Grand Prize, although he would shortly drop the faux title and the ‘h’ for a less Germanic-sounding ‘k’ (‘to take the Hun out of my name’). The ignition wires of his Maxwell were swamped in the rain after 41 laps. None in the Maxwell team (Barney Oldfield and Bill Carlson) did any better, which rubbed salt in a wound; Rickenbacher had only just signed on with Maxwell, as his previous car, the remarkable 1914 Peugeot EX3, had given trouble in his previous two races. That very car was given to Anglo-Italian driver Dario Resta, and Rickenbacher soon regretted the swap, considering the switch to Maxwell the biggest mistake of his career. He made up for all this two years later, earning the Croix de Guerre and Légion d’Honneur as the ‘Ace of Aces’ in France, flying Nieuports and SPAD XIIIs like a racing driver, with 26 confirmed kills.

Regardless of the rain and relatively slow track, the Grand Prize was spectacular. Observers ‘watched the muddy champions of this modern tournament thunder by, through avenues of dripping palms, under the calm, travertine scrutiny of Cortez and Pizarro, who never got up more speed than 12mph in their somewhat important lives.’ The race was finished by 6pm, in gathering darkness, by which time ‘everybody had enough’. 104 laps of the course made 400.29 miles, and almost 8 hours later, Dario ‘Dolly’ Resta had won his first race in America, driving the revolutionary Peugeot EX3 at an average speed of 56.13mph, winning $3000 in the process.

Resta was followed 6.5 minutes later by Howard ‘Howdy’ Wilcox in his Stutz, which netted him $2000. There were only 11 cars still circulating, battling valiantly for 3rd place (and $1500) under the electric lights of the elegant Avenue of Palms, the Esplanade, and the board track. Hughie Hughes emerged next with his ‘Ono’ special, a Fiat chassis with Pope motor. Fourth went to Gil Anderson in another Stutz ($1000), and 5th to Louis Disbrow in a Simplex ($500 prize). A summary of the Expo explained, ‘We note the names of these cars not to advertise them gratuitously, but because they may be of interest 10 years hence.’ Or even one hundred years! After these gents came in, the race was stopped and the remaining 6 drivers called in, no doubt to their relief. The slippery race had surprisingly few mishaps, which were related thus: ‘A wheel was broken, a tire flew off, a car went through the rail, several others skidded into the baled hay, and a dog was killed. Nobody was hurt, but the crowd lived the rainy hours in constant apprehension, which is what a crowd likes to do.’

Because of poor weather, the Vanderbilt Cup was postponed to March 6, and was a much shorter event of 300 miles/77 laps. The day dawned bright and sunny, and the crowd had swelled to over 100,000 by the 12:30 start time. The lineup for the Cup was nearly identical to the GP, although drivers Cooper and Taylor were out, while T.A. Tomasini, Harold Hall, and ‘Wild Bob’ Burman were added, giving a total of 31 cars. Drivers were flagged 3 abreast at 15-second intervals, and Ralph DePalma with his 1913 Mercedes burst into the lead. That didn’t last long, as his car was plagued with vibration, and Eddie Rickenbacher surged ahead for the next 6 laps in his Mercer, until he broke a fuel line. The Deusenberg of Tom Alley held the lead until lap 20, when Dolly Resta passed him, with Tom Pullen in the second Mercer right on his tail. Resta was the only the foreigner in the race, and as yet unknown to fans, so when Pullen passed him on lap 23 the crowd was thrilled. By lap 30, though, Resta had secured top spot again, and ‘Wild’ Bob Burman in his Case passed Pullen too.

As the track was dry, speeds were up, as were accidents, including one car that passed the grandstands engulfed in flames – just the thing to build a fan base! The first mishaps were courtesy the Deusenberg camp, as Tom Alley mowed down 150’ of fencing on lap 37, while Eddie O’Donnell sideswiped a haybale and slid his car on its side – luckily neither driver was hurt. On lap 40, Harvey ‘Captain’ Kennedy lost a wheel from his Edwards Special, which struck and injured a spectator, as they do. Not long after, ‘Wild’ Bob Burman made a display of his Case racer outside the Palace Of Machinery, rolling the car and breaking his mechanic’s thigh and a couple of ribs. Inside that very Palace, Henry Ford had set up a complete Model T production plant, and new cars rolled off an assembly line every few minutes.

Bob Burman was a pivotal figure in American racing; after wrecking his Case, he secured a Peugeot for the remaining 1915 season, but broke the crankshaft in the Point Loma race (San Diego). Despairing, Burman gave designer Harry Miller and machinist Fred Offenhauser $2000 to modify the DOHC, 4-valve Peugeot engine, which needed shrinking to fit the new 5-liter formula for the Indy 500. The engine was transformed with Miller-designed light alloy cylinder/heads, tubular rods, a pressurized oiling system, stronger crank, and 293 cu” displacement – and the Miller/Offenhauser engine dynasty was born. And after lopping 200lbs from the chassis, Burman lapped the Peugeot factory team cars at Indy.

Harry Grant’s Vanderbilt Cup race was a less dramatic, but more frustrating affair, as on lap 50, his pit crew watered his fuel tank, and fueled his radiator. The Mercers were the best American team, constantly dogging Resta, but Glover Ruckstall broke an axle on lap 72, while Pullen, having run 2nd for half the race, had to stop and secure a loose fuel tank, which cost him a place as ‘Howdy’ Wilcox snuck past, and retained his lead, making the 1-2 finishing order of the Vanderbilt Cup the same as the Grand Prix. Pullen settled for 3rd, and Ralph DePalma 4th in his 140hp Mercedes-Benz Grand Prix. He had won the Vanderbilt Cup twice before, and purchased his Mercedes directly from Paul Daimler at the factory in Untertürkheim, paying $6000. When the car was ready on July 24th 1914, Daimler gave him the car’s documents and a map to the Antwerp docks, telling him to leave immediately; he shipped the car on the German steamer ‘Olympic’, and took a passenger liner from Le Havre, learning mid-voyage that war had broken out. While he didn’t win the Vanderbilt Cup, he did win the Indy 500 later that year with the Mercedes, several laps after breaking a connecting rod!

Dario Resta won the 300-mile Vanderbilt Cup in 4hrs, 27 minutes, 37 seconds, at an average speed of 66.25mph. He also won a second $3000 prize, plus bonuses (eg, Bosch gave him $400), and was clearly king of the course – wet or dry. While the PPIE track didn’t exist a year later, it was the first time a driver had won both the Grand Prix and Vanderbilt Cups. He’d exhibited great chivalry in stopping to check on Burman’s flipped car mid-race, and must have had quite a bit in hand to do so and still win by 7 minutes. The actual Vanderbilt Cup was made of silver by Tiffany’s, and was worth a cool $5000, as was the smaller but solid gold cup for the Grand Prix. Racing at this level was a rich man’s game, and hardly profitable, but Dolly Resta had earned enough for an upgrade, and promptly bought a new Peugeot EX5 for the rest of the 1915 season.

Related Posts

December 5, 2017

The Vintagent Classics: The Hazards Of Helen: The Wild Engine

The spunky Helen (Helen Holmes) is our…

October 2, 2017

The Vintagent Selects: The Monkey & Her Driver

Kendra and Betty are America’s only all…

wonderful! my great grandfather on my mother’s side had a car that looked like one of these racers in his barn in Patterson,along with a huge harvester that used a 20 mule team in it’s time to pull it

Those early Wall of Death images are fantastic!

A little known fact, Cranston, R.I. had the first organized race track in the country. It started out as a trotting track for live stock, and turned to auto racing.

Richard, do you have any reference or photos of this track? Just out of curiosity, sounds like a good story to pursue! Paul@thevintagent.com