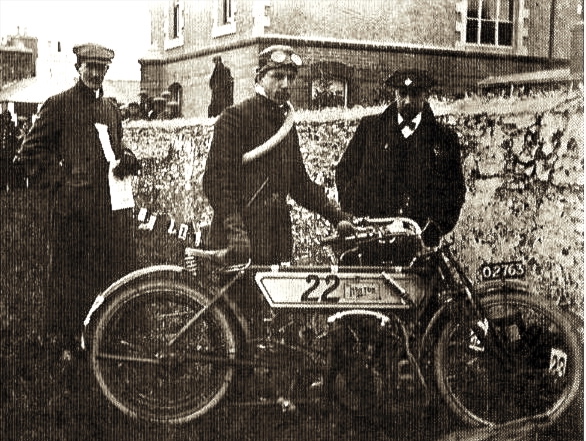

The first TT races were held on May 28th 1907, over a 15 3/4-mile course, which did not include the mountain road over Snaefell, as the motorcycles were all single-speed, clutchless, virtually brakeless, and incapable of such a climb, or descent! Two classes, for single- and multi-cylinder machines, had to abide by 90mpg fuel economy (for singles; 75mpg for multis). Famously, Harry Collier, an organizer of the race, on the Matchless single of his own make, and Rem Fowler on a Peugeot-engined Norton, won their respective classes in just over 4 hours time, at average speeds of approximately 42 mph. They each received a 3-foot tall sculptural trophy of Mercury atop a winged wheel, donated by the Marquis de Mouzilly St. Mars, replicas of which have been handed over to brave TT winners for 100 years. The early races were run over gravel farm tracks at speeds touching 70mph, when punctures, crashes, flaming machines, and livestock encounters were common. Boy Scouts with flags marshaled the course, waving frantically to warn of upcoming dangers. The need for improved machines (and roads) was dramatically emphasized by the death in practice for the 1911 TT of Victor Surridge on a Rudge, outside the Glen Helen Hotel. Thus was born a chorus of objections to the races by the safety brigade, as the treacherous nature of the road course claimed a mounting share of victims.

In 1911, the race moved to the current 37 ½ mile ‘Mountain’ course, to create a greater challenge to the motorcycles, which were becoming faster and more reliable, but still needed development in braking, gearing, and handling. In that year Indian ‘motocycles’ had all these things, using all-chain drive with a clutch and two-speed gearbox, and an effective drum brake on the rear wheel instead of the usual bicycle-type stirrup. Their reward was a 1-2-3 sweep of the Senior races, which lit a fire under British and European manufacturers to rapidly modernize their designs. Indians did well at the TT for another 12 years, with their last podium placement in 1923, when Freddie Dixon, the legendary racer-tuner, took 3rd place.

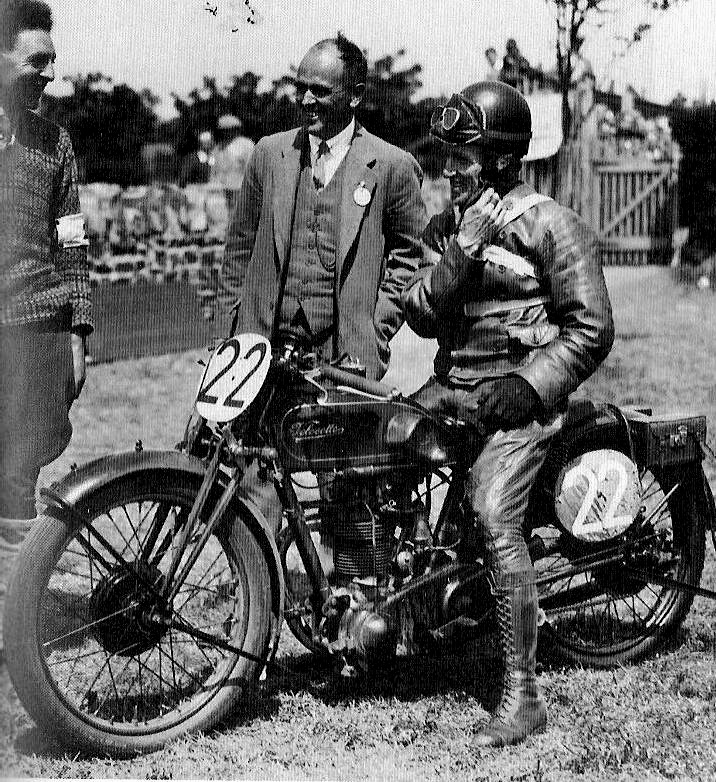

By the 1920s every competing manufacturer had developed recognizably modern designs, with brakes on both wheels, suspension (at least up front), clutches, and multiple gears. More entries from Europe began to appear (Peugeot, FN, Bianchi, Moto Guzzi, etc), the road surface had improved, and by 1922 the course was almost fully paved(!); race averages crept up into the 70mph range for the 500cc Senior class. The great variety of engine configurations in competition (side-valves, inlet-over-exhaust valves, overhead valves, overhead cams, and two-strokes) made for a fascinating study in the possibilities available to the motorcycle designer at the time. The keenness of competition was reflected in the sheer number of different TT makes; AJS, Levis, New Imperial, Sunbeam, Rudge, Rex-Acme, Velocette, Douglas, DOT, Cotton, Scott, and HRD all won top honors in the ’20s.

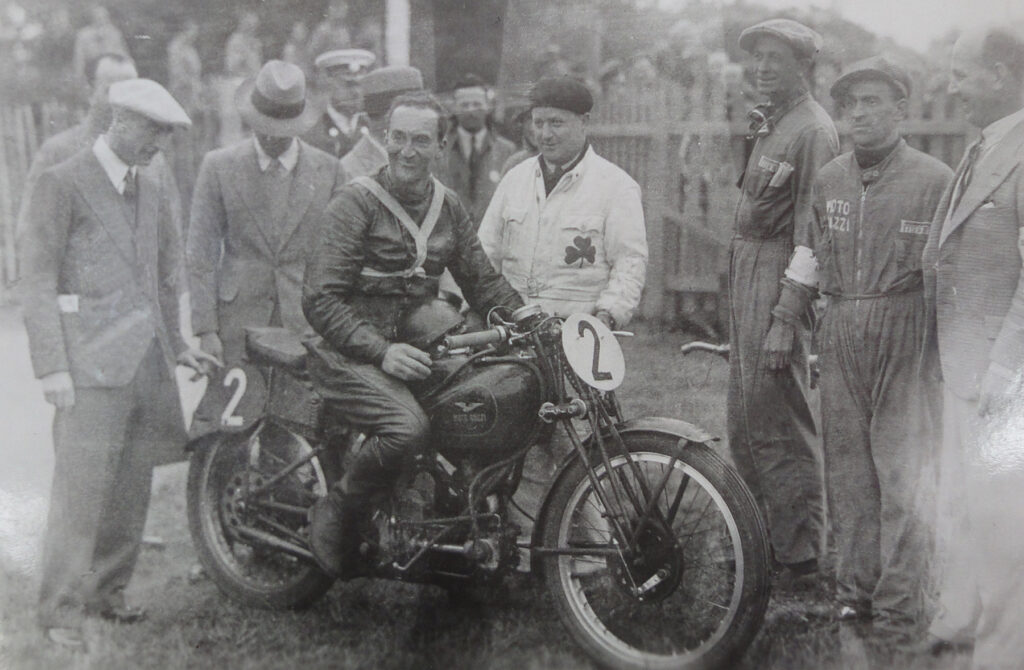

By the 1930s all winners of the Senior (500cc) and Junior (350cc) TTs had camshafts on top of their engines, and lap records touched 90mph. Only in the Lightweight (250cc) class was mechanical variety maintained, with OHV, OHC, and two-stroke machines nudging their way to the podium. Race machinery had strayed from the original intention of ‘same as you can buy’, as European uber-bikes (Gilera, Moto Guzzi, NSU) with multiple cylinders and superchargers began menacing the track. Still, Norton, with its 500cc Model 30 (Manx Grand Prix), and Velocette’s KTT 350cc models began a long string of success on the Island, which would last until the 1960s. Race watchers were used to British wins in all but the lightweight classes had regularly broken into the top 3, so it was a shock when Moto Guzzi in 1935 won the Senior TT, with Stanley Woods (10-time winner) at the helm. His mount was notable not only for its wide-angle OHC v-twin motor, but also for the effective rear suspension. By the next TT, all serious contenders had rear shocks!

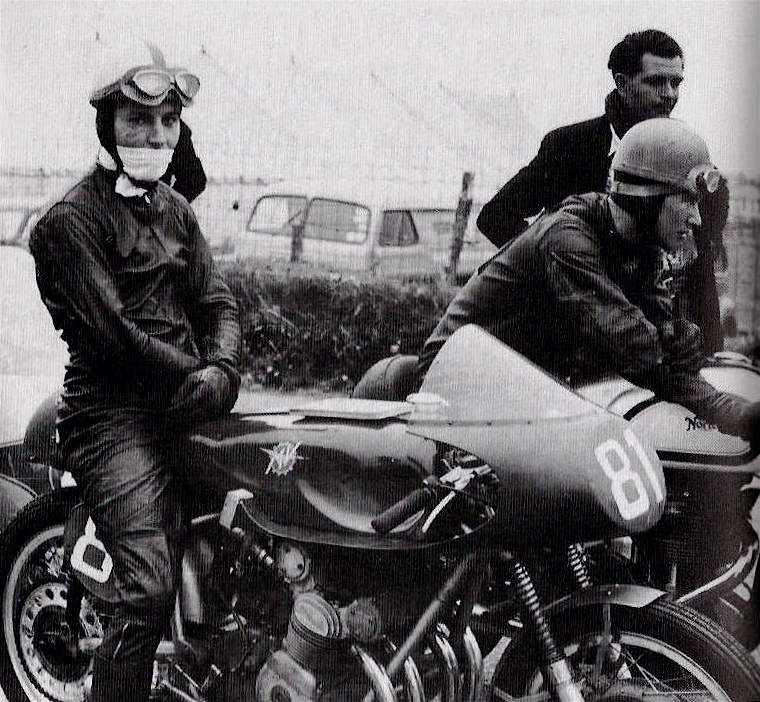

AJS and Velocette had their own answers to the ‘multi’ brigade in their V-4 and Roarer twin, but BMW, using its characteristic flat-twin (but with an OHC supercharged engine) won the Senior TT in 1939, on the very eve of the WW2. Supercharging was henceforth banned from the races. Racing resumed in 1947, with the essentially pre-war designs of Norton, Velocette, and Moto Guzzi dominating their respective classes for a few years as the rest of Europe rebuilt. In the 1950’s though, Italian (Guzzi, Gilera, MV) and German (NSU, BMW) machines came to the forefront with new and sophisticated multi-cylinder designs, culminating in the amazing Guzzi V-8. Bob McIntyre made the first 100mph lap in 1957, on a 4-cyl dohc Gilera.

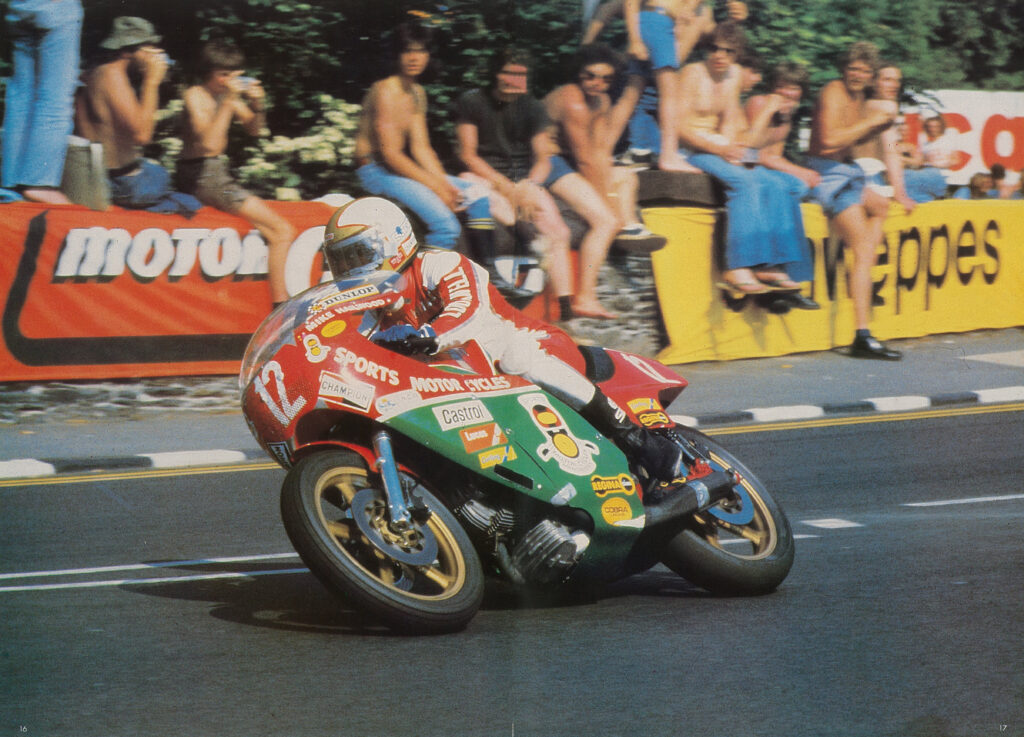

By the mid-1950’s most British firms allowed their factory teams to languish, refusing to spend the vast sums demanded by race programs bearing no relation to consumer motorcycles. In 1957, most European manufacturers concurred by closing their race shops, leaving MV and BMW to battle privatateer racers using Manx Nortons and AJS/Matchless production racers. By the 1960’s, Japanese machinery, led by Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha, virtually took over the Lightweight TT. Honda began contesting the larger classes as well, using technically superior 4- and 6-cylinder double-overhead-cam engines, and the battles between Honda and MV became the stuff of legend. Honda quit racing in 1967, leaving Agostini on his MV Agusta to win all Senior and Junior TT’s from ’68 to ’73 (minus the ’71 Junior). The organizing body – ACU – introduced the Production TT in 1967, and later Formula One and 750cc classes among others, to maintain variety in what had become a Japanese and MV benefit. Racing in these new categories became as closely watched as the ‘classics’, especially the 750cc TT, where one could watch similar-to-standard Superbikes from Norton, Triumph, and Honda duke it out. The Senior and Junior races were dominated from 1974 by Yamaha two-strokes, challenged by Suzuki later in the decade. Lap averages hit 110 mph, and a clamor from top riders such as Giacomo Agostini, Phil Read, and Barry Sheene, resulted in the TT losing its World Championship status in ‘76. A high note in 1978 was the comeback of Mike Hailwood, riding a Ducati to win the Formula 1 race after a 10-year absence; good publicity for the TT at a time when calls for its total cancellation had reached a peak.

In the 1980’s and 90’s, race averages began to reach 120mph, and Joey Dunlop began his remarkable run of 26 wins. Lap speeds now stand at over 130mph, and the increasing number of spectators and participants show the irresistible draw to motorcyclists across the globe, who want to experience the legendary race course and steep in its century of speed.

Thank you for composing this amazing article.

I love motorcycle, I don’t know how many of these things, over the years and never won a thing.

More details in my blogI love biker

MARCH 18, 2007

I always enjoy your articles on the history of motorcycling. It is nice that you take the time to document the early days.

I’m just a dumb Harley guy, but I have owned a couple of Triumphs in the past. I miss those Trumpets!

Keep up the good work!

Fatboy Bobcat

Great Article, the Isle of Mann TT is on my bucket list to attend until then riding the Kancamagus Hwy and riding the Mount Washington Auto road will have to suffice! Keep up the great work at The Vintagent!

The post is engagingly written, covers the key points, and really does connect the dots. The Sands of Time takes readers on a wild ride through a century of action.