Those activities ultimately sent him to jail where, he said, he had a chance to rest up, relax and reconsider. When he emerged, he began focusing entirely on custom car and motorcycle work. Then, when he found that his affiliation with the outlaw club was hampering his career as a designer and builder – a National Geographic TV show and an exhibition at the Autry Museum of the American West, he said, both got spiked because of his membership – he left the club and set out on his own.

One custom paint job depicts the late narcocorrido superstar Chalino Sanchez, whom Ordaz identifies as “like a Mexican Tupac.” Another pays tribute to the 1970s Mexican TV series “Chespirito.” Another, for a Black client, features images of African-American icons Martin Luther King Jr, Malcom X, Frederick Douglass, Huey Newton and Barack Obama. The four unfamiliar faces on the gas tank? “Those are family members who were killed by the police,” Ordaz said. In a loft high overhead are two or three vicla bicycles, the stretched and lowered Schwinns that may have been the progenitors of the current motorcycle versions.

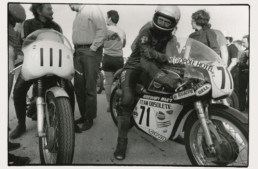

A new menace is gentrification. Outsiders have come to Inglewood for the central location and lower real estate prices. Every week, Ordaz says, another house changes hands. “All of a sudden, the old family is gone and there’s some white people walking a dog.” On that Sunday morning in Elysian Park, a dozen bikes bearing Malo’s handiwork were scattered along Stadium Boulevard. Though he’d only started organizing the event a week before, turnout was strong. He was greeted with back slaps, handshakes and bro-hugs by the very mixed crowd. Over here were couples arriving two-up, single females riding alone, alongside OGs on blacked-out hogs, parked next to a group of about 25 members of a three-patch motorcycle club.

Much like lowriders this just aint my thing ( too over the top for my introverted keep it simple aesthetics ) But also just like lowriders there’s no denying the craftsmanship , engineering and artistry that goes into this .

So … as with lowriders …. I’ll respect , admire .. and appreciate .

But being in Denver … gotta tell ya .. I’ve seen no evidence of VILCA here … as in ZERO .. on the road … in the neighborhoods ..or at the shows … and lets face it … these’d be impossible to miss … but … I’ll keep my eyes open … and let you know .

😎