The SoCal 'Vicla' Scene

In the burgeoning Vicla scene in Southern California, a Chicano cultural mashup that fuses traditional Mexican-American lowrider aesthetics with all-American V-twin muscle, there is agreement on only one point: “Vicla” is a Spanish slang word for “bicycle,” and it probably was born a century ago somewhere in South Texas. The scene itself is very clear, and very vibrant. On a drizzly January morning in Los Angeles’ Elysian Park, more than 200 Vicleros and Vicleras gathered to celebrate and show off their highly decorated machines. Astride Harley-Davidsons baggers and cruisers, almost exclusively, they roared into the shadows of Dodger Stadium to pose for photos, listen to live ranchero music, eat tacos, drink beer and swap stories.

Those activities ultimately sent him to jail where, he said, he had a chance to rest up, relax and reconsider. When he emerged, he began focusing entirely on custom car and motorcycle work. Then, when he found that his affiliation with the outlaw club was hampering his career as a designer and builder – a National Geographic TV show and an exhibition at the Autry Museum of the American West, he said, both got spiked because of his membership – he left the club and set out on his own.

One custom paint job depicts the late narcocorrido superstar Chalino Sanchez, whom Ordaz identifies as “like a Mexican Tupac.” Another pays tribute to the 1970s Mexican TV series “Chespirito.” Another, for a Black client, features images of African-American icons Martin Luther King Jr, Malcom X, Frederick Douglass, Huey Newton and Barack Obama. The four unfamiliar faces on the gas tank? “Those are family members who were killed by the police,” Ordaz said. In a loft high overhead are two or three vicla bicycles, the stretched and lowered Schwinns that may have been the progenitors of the current motorcycle versions.

A new menace is gentrification. Outsiders have come to Inglewood for the central location and lower real estate prices. Every week, Ordaz says, another house changes hands. “All of a sudden, the old family is gone and there’s some white people walking a dog.” On that Sunday morning in Elysian Park, a dozen bikes bearing Malo’s handiwork were scattered along Stadium Boulevard. Though he’d only started organizing the event a week before, turnout was strong. He was greeted with back slaps, handshakes and bro-hugs by the very mixed crowd. Over here were couples arriving two-up, single females riding alone, alongside OGs on blacked-out hogs, parked next to a group of about 25 members of a three-patch motorcycle club.

Road Test: 2020 BMW R18

The Vintagent Road Tests come straight from the saddle of the world's rarest motorcycles. Catch the Road Test series here.

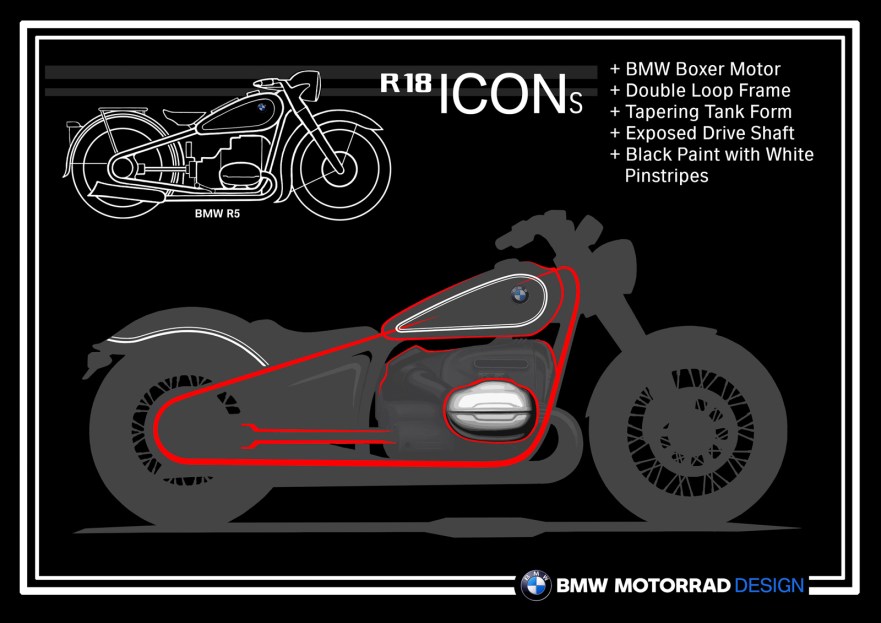

BMW’s R18 has arrived with a splash. In mid-September the German company conducted a press rollout of its highly-designed new cruiser with the motorcycle industry’s first elaborate COVID-period ride event – swank hotel headquarters, full staff greeting media, full fleet of bikes, ride leaders and brand photographers and videographers -- unwilling to wait any longer to introduce its dramatic new machine to the waiting world.

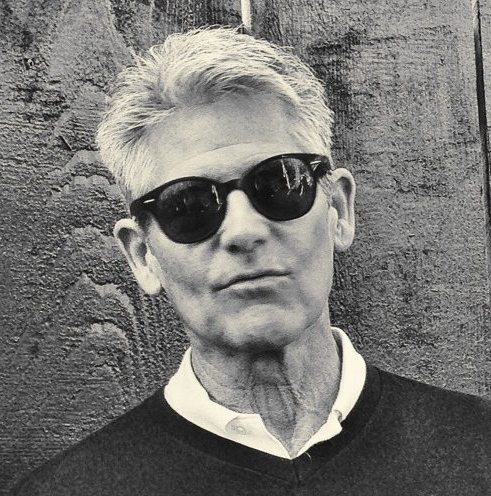

Long in the planning, the R18 owes its stylistic inspiration to the R5, a street model the company produced from 1936 to 1937. This provided the essentials: The boxer engine, double-loop tubular steel frame, exposed nickel-plated drive shaft, teardrop gas tank, fishtail exhaust pipes and signature black paint with double white pin stripes.

The bike draws its economic inspiration from elsewhere, and is the answer to a question many people have asked – many executives, anyway, if not many consumers. Like many companies, BMW has been wondering why Harley-Davidson dominates the cruiser market with what one BMW executive derided as a second-rate product – and trying to figure out how to take away some H-D market share. (And, of course, as its own fortunes have waned, H-D is trying to figure out how to take away some of BMW’s market share, by introducing its PanAmerica adventure bike into a segment dominated by GMW’s GS line.)

“Harley-Davidson runs this segment, but that’s changing,” BMW Motorrad US product manager Vincent Kung said during a live-streamed R18 presentation. “A new generation is coming in, a generation that’s thinking differently. They’re experiencing what I call ‘Harley fatigue.’”

They also acknowledge that 75% of the hoped-for buyers will be “conquest” customers – buyers who will need to abandon another brand, many of them forgoing their wish to buy American, as first-time BMW owners.

So, has it?

The bike is beautifully built – “Berlin made,” advertising material say, and it even says so on the speedometer – and beautiful to look at. The black is rich and deep. The chromed parts – the introductory model, known as the R18 First Edition, is laden with nearly $4,000 in upgraded bits and bobs – gleams. The look and feel of real metal abounds. There are no chromed plastic parts, anywhere on the bike. The fit and finish are BMW standard – superb. The overall look is trim and clean. There are practically no visible wires or cables.

The engine rumbles to life, roughly, with a push of the electric start, and then settles into a gentle purr. A flick of the throttle produces the signature boxer roll. Clutch in, transmission engaged – with a reassuringly industrial “clunk” – and away.

Because it was clear from the start to the designers that their R18 must be powered by the company’s iconic horizontally-opposed twin-cylinder engine, it was also clear that the R18 could not feature the “foot forward” seating position favored by other cruisers. Instead, the R18’s builders placed its footpegs in a position they call “mid-mounted,” almost directly below the seat.

The massive R18 engine’s power is delivered via a six-speed transmission and through three ride modes. BMW, seeking to be clever, has named them Rock, Roll and Rain, with Rock being the most aggressive. Horsepower and torque remain the same with all three. Only the delivery of power is altered.

But it’s a big bike. Slow-speed maneuvering required some concentration. Stopping at red lights and stop signs became tedious. The mid-central footpegs required my foot to come up, out and back before they hit the ground, as the big boxer cylinders prevented any forward movement.

Parking was less of a challenge, because the R18 is fitted with a rudimentary reverse gear. Put the bike in neutral, pull a switch near the left-side footpeg, and use the starter button to engage an electric motor that rolls the machine backward.

The oil- and air-cooling system limited engine heat. For Southern Californians, anyway, this is an issue. Many of the big twins, from most Harleys to most Indians and beyond, contribute so much ambient heat that riding them on hot days can be a challenge.

The longer I rode the R18 the more impressed I was by its craftsmanship, elegance and curb appeal. (I experienced more spectator attention -- “Cool bike man!” -- than on anything I’d ridden since the last quirky-looking Ural I piloted.) But I was happy to stop riding every time I stopped, and eager to dismount. By the end of the four-hour ride, I was ready to quit, which is exactly the opposite of how I feel at the end of most rides.

BMW has high hopes for the R18. The company’s CEO Markus Schramm said BMW Motorrad’s ambition is to “become number one in the premium cruiser segment worldwide.” Schramm said sales are strong, with a backlog of orders globally and the factory working at full speed to fill them.

It will be an interesting experiment. Though BMW posted record sales numbers for the month of June of this year, the six months before that saw a sharp decline, with numbers down from the comparable 2019 period by nearly 18%, according to company reports.

There was probably more reason for optimism, in June, that further prosperity was just around the corner. Now, with the coming of fall, the approaching of winter, the continuing financial uncertainty and the pending end of state and federal support for struggling businesses and unemployed workers, the R18 may have arrived just in time to sneak into 2020 before the year closes.

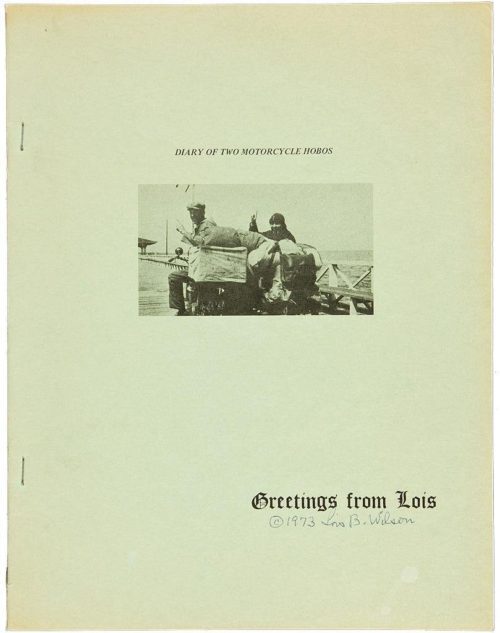

Bill and Lois' Big Adventure: the Foundation of A.A.

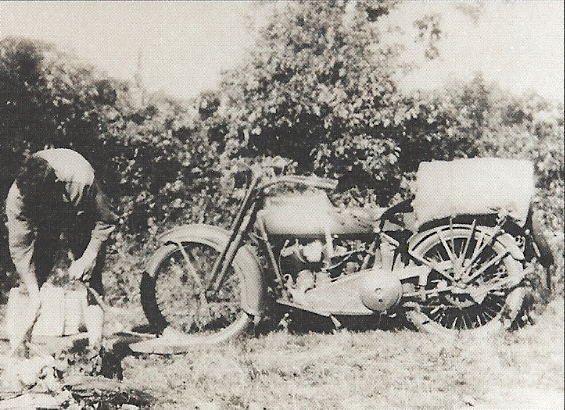

In April 1925 Bill Wilson and his wife Lois left Brooklyn, New York riding a Harley-Davidson on a journey through the Eastern United States. Wilson was an energetic stock speculator who at age 29 was struggling to develop a method of predicting rises in stock values. He believed the secret was better information about the inner workings of publicly-held corporations. He and Lois, then 34, planned to spend as much as a year visiting factories and home offices of companies that looked promising.

Forced occasionally by bad weather to pay for food or shelter, despite their best efforts to camp wherever possible and feed themselves by fishing and foraging, the Wilsons were soon out of funds. In July, they found a farmer who was willing to take them on as summer help – Lois cooking and cleaning, Bill repairing farm equipment and doing general labor. Through the fall and winter they were back on the road, fighting the falling temperatures with a newly-acquired windshield for the motorcycle and a mattress and hot water bottle for the sidecar. Bill continued to visit cement factories, electric power plants and other companies – even getting invited to a private display of the new cinema development known as “talking pictures” – while sending reports back to his friends on Wall Street. One was sufficiently impressed to send the Wilsons some much-needed money.

Lois’ plan to keep Bill sober was only moderately successful. She managed to keep Bill away from the bottle for weeks at a time. But whenever alcohol was present, and he took a drink, extreme drunkenness followed. One time he stepped away from Lois saying he needed cigarettes, and did not return. Left alone on the street, with no money, in a strange town, Lois waited for hours until, well after dark, she began to search from one barroom to the next. “At last I found him, hardly able to navigate--and the money practically gone!” she wrote. Bill’s plan proved more effective. By the time he’d finished his tour of the east coast, he had convinced backers on Wall Street to invest in his companies and bankroll his own investments. Soon he and Lois were back in New York, living like royalty. “For the next few years fortune threw money and applause my way,” Bill said later. “I had arrived.”

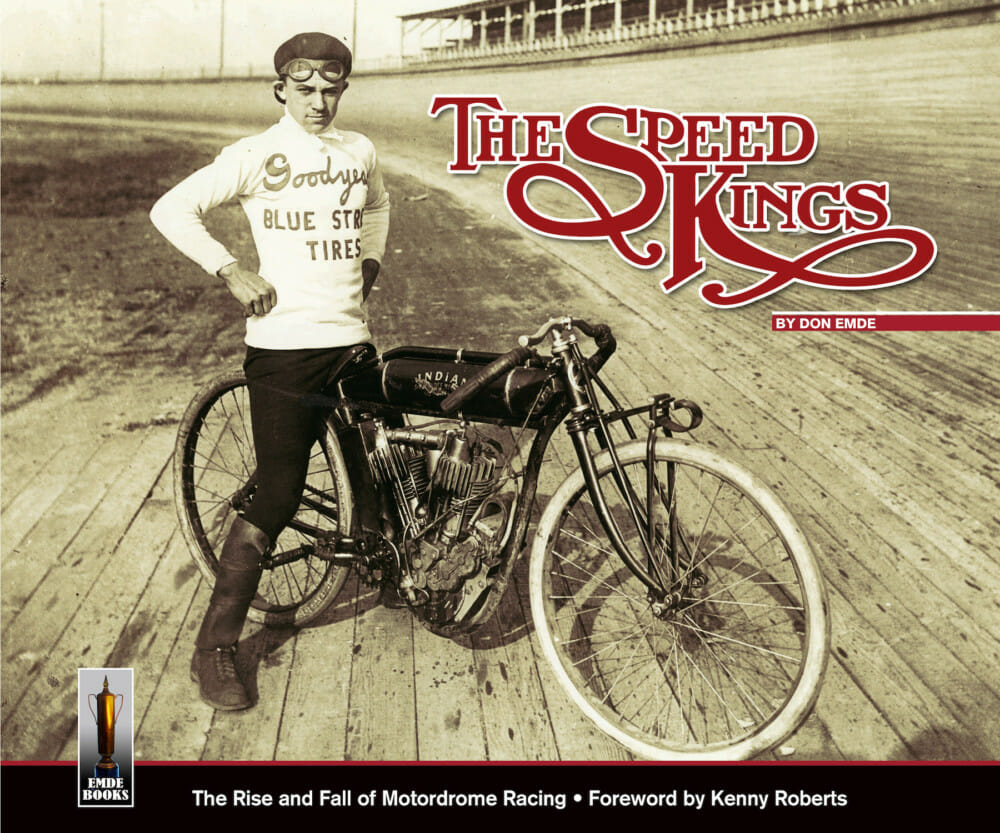

Book Review: 'The Speed Kings'

Book Review by Charles Fleming

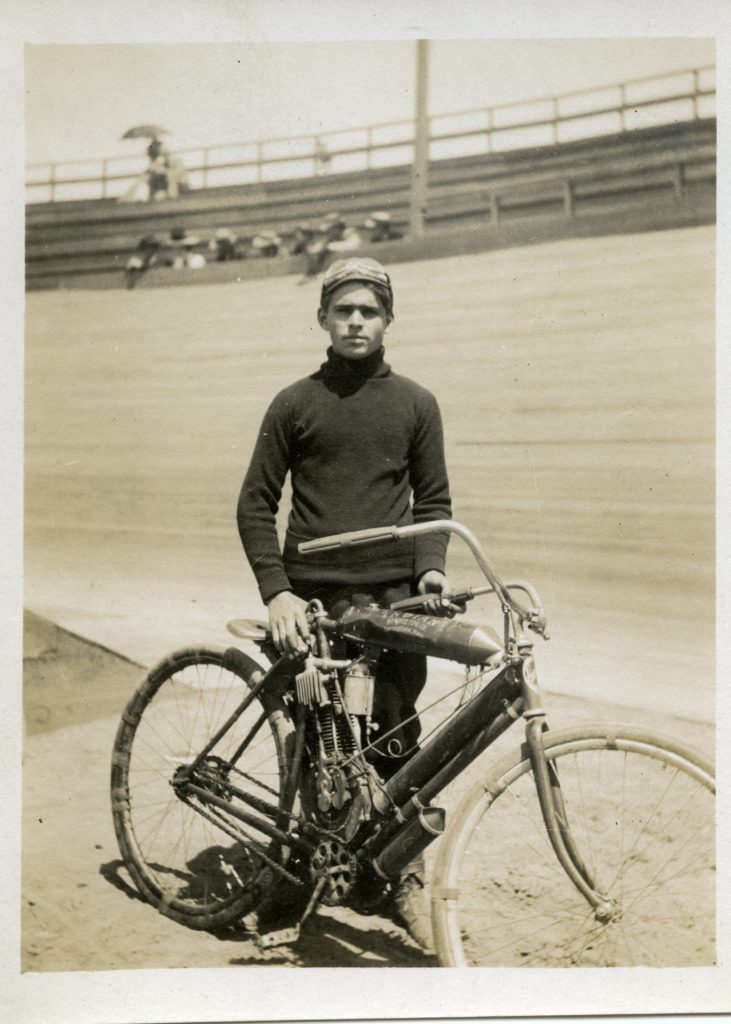

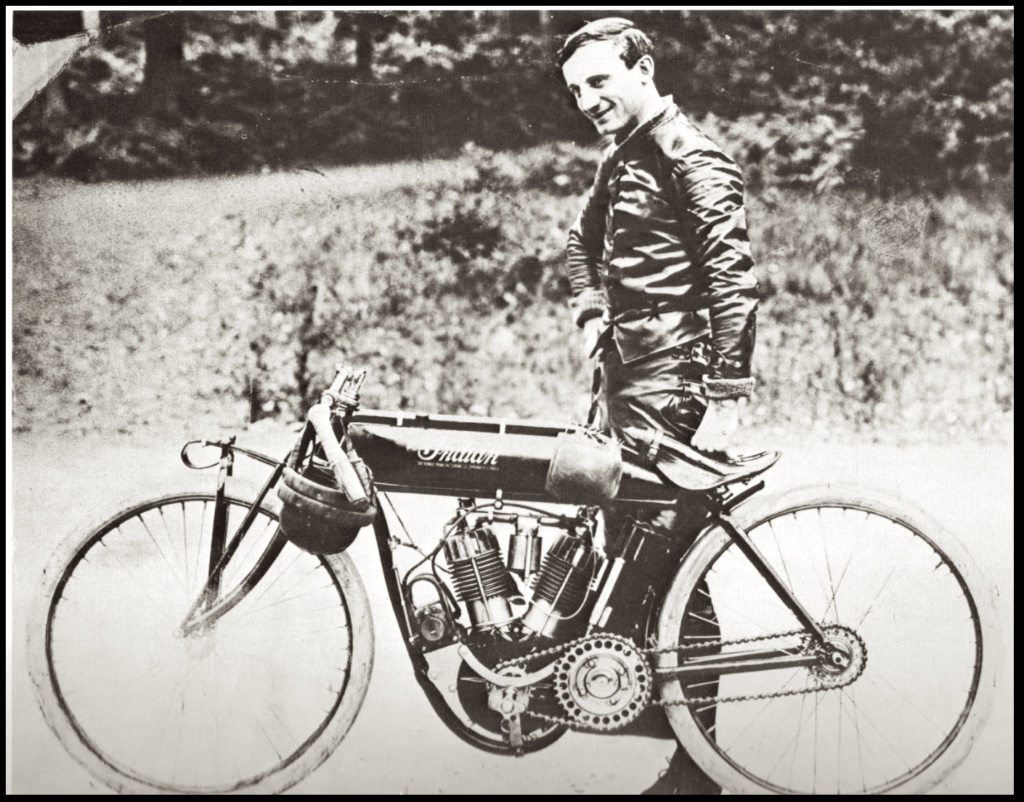

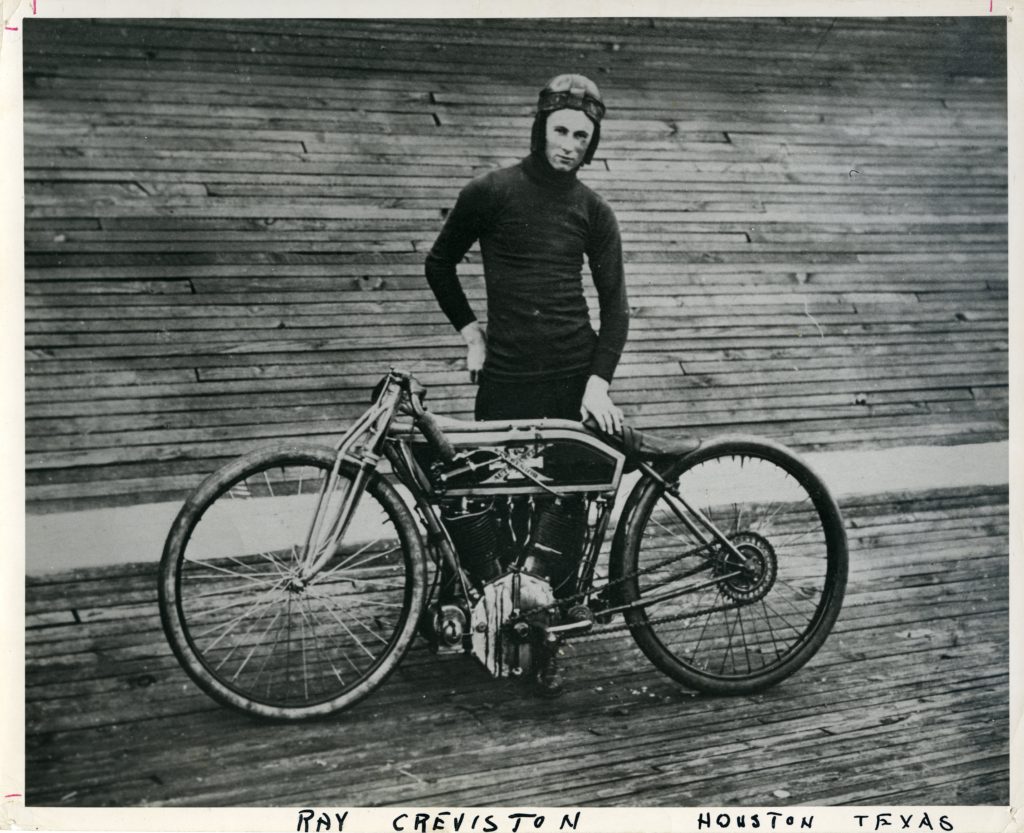

In his expansive new book 'The Speed Kings', motorcycle historian and Daytona 200 race winner Don Emde has chronicled the meteoric rise and tragic fall of American board track racing, which at its peak in the early 1900s rivaled baseball as America’s number one spectator sport and made its champions into the country’s first national sports heroes. Emde spent four decades collecting images and information on “motordrome” racing, which flourished in the U.S. between roughly 1909 and 1914, ultimately compiling 6,000 pages of data. From this he has created a dense, oversized coffee table book, massive in scope and weight, packed with the ephemera of a bygone era. Included are more than 600 photos.

Heiwa Motorcycle and Kengo Kimura

The rain began to fall just as I stepped into the door of Heiwa Motorcycle, a dimly lit, overstocked, two-story industrial space on a narrow spit of land near the port of Hiroshima. The sky outside had a heavy, ominous look. The oncoming rain was the beginning of a monsoon storm that would eventually force millions of western Japanese residents to evacuate their homes, and cause flooding that would take more than 225 lives. Inside, Heiwa workers were choosing strategic locations for metal pans to catch the water finding its way through the corrugated metal roof, and moving racks of vintage clothes and shelves of collectible Thermos bottles, lunchboxes, plates and cups that Heiwa stocks in its cluttered second-floor second-hand store.