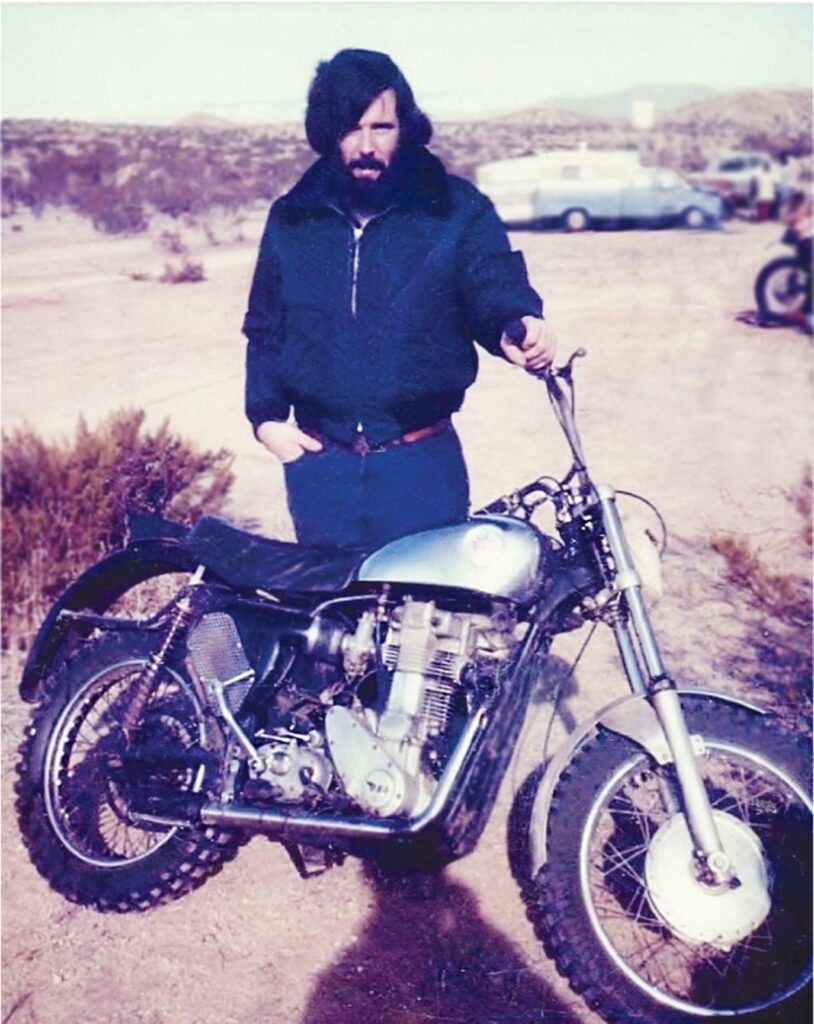

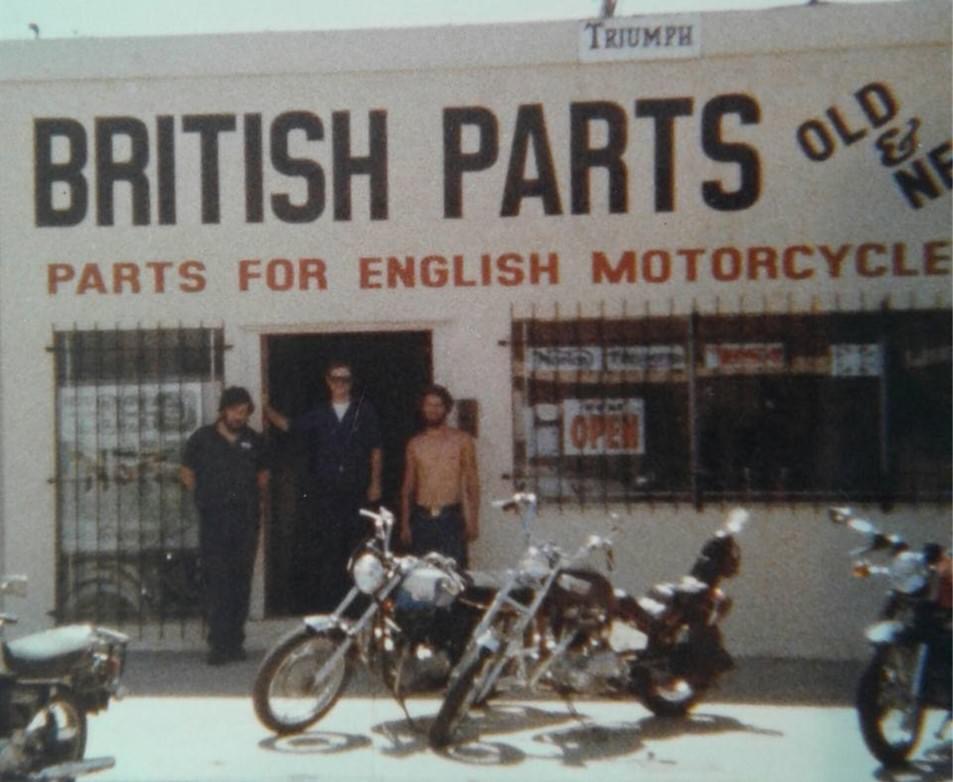

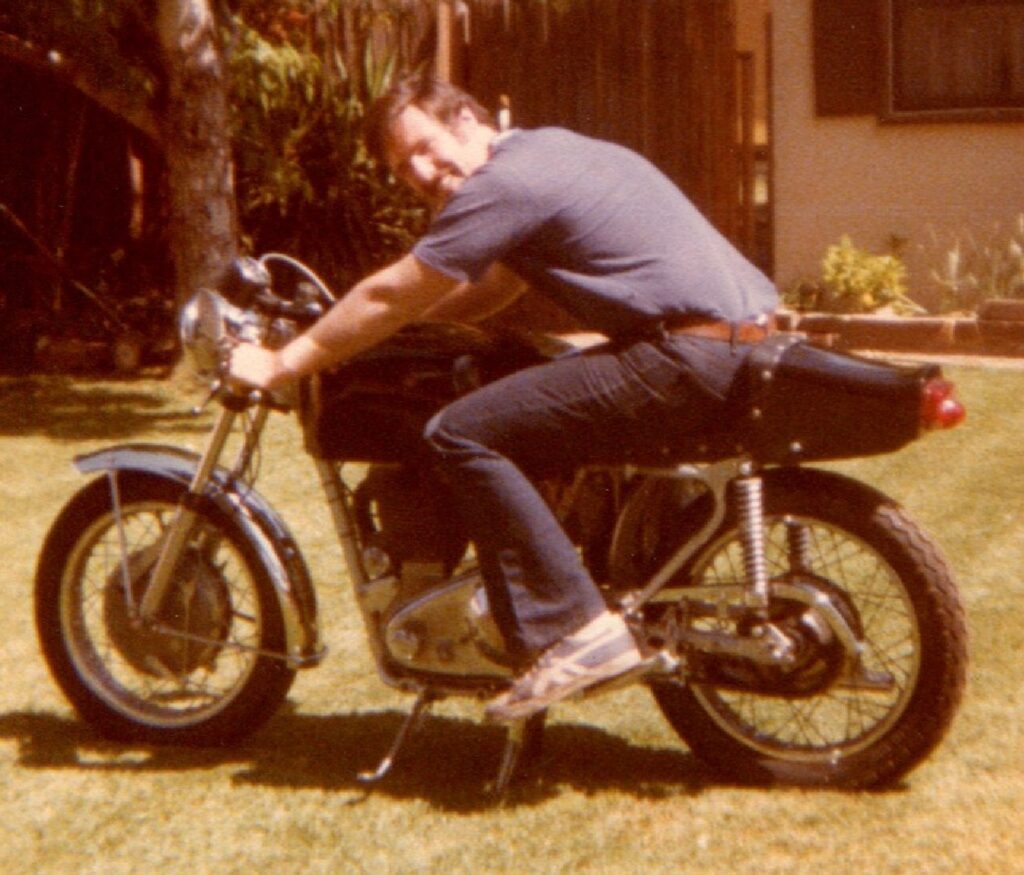

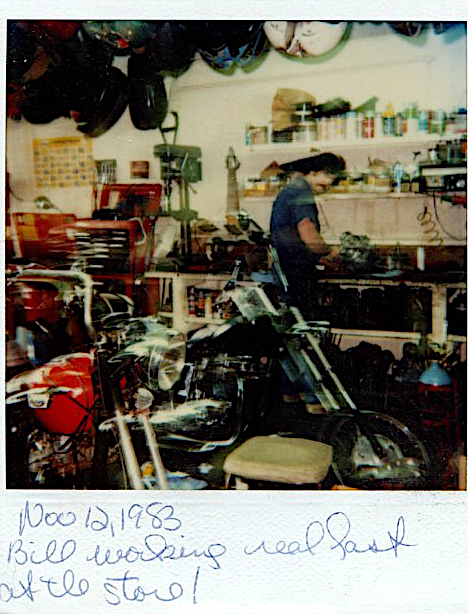

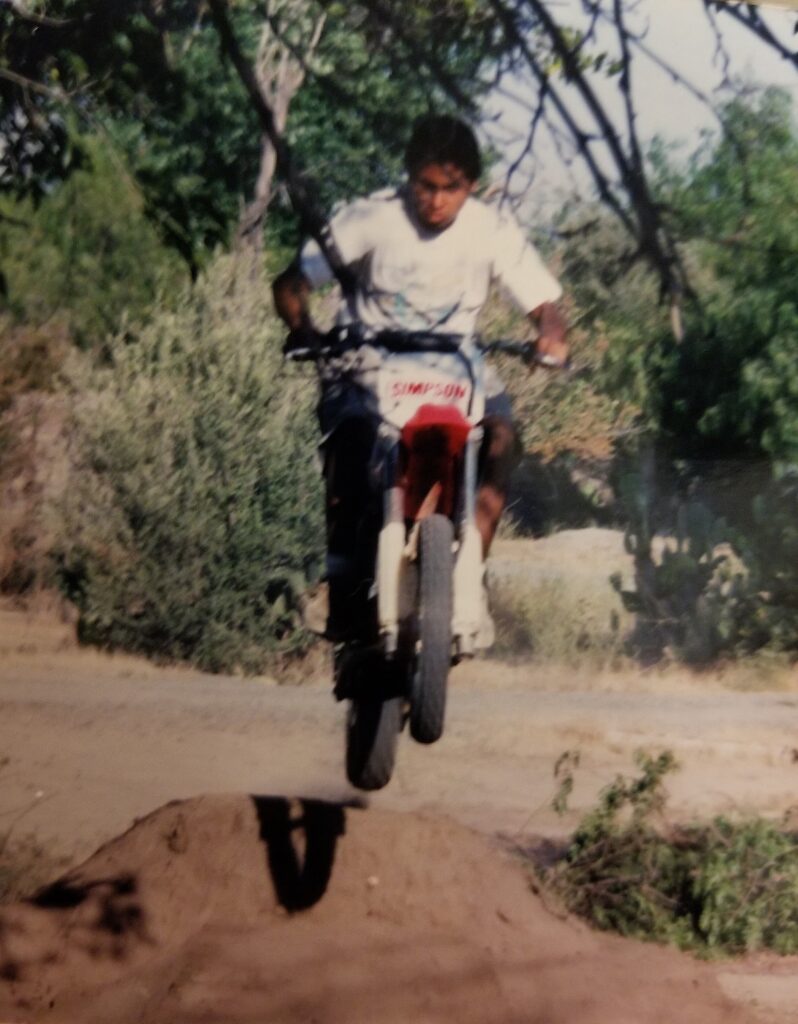

Here’s a novel idea. If you have more than, say, five or six motorcycles and you have the means to do so, give one away to a young person. For years, that’s what Bill Getty of JRC Engineering in Perris, California has been doing. Importantly, more than just giving away the machine, Bill also mentors the kid and figures he’s passed along close to 100 motorcycles – thus introducing dozens of youngsters to the thrills of riding. As aging enthusiasts bemoan the lack of enthusiasm for motorcycles among Teens and pre-Teens, isn’t this one solution? The idea harkens back to Bill’s early days as a Boy Scout; he wasn’t given a machine, but Bill’s Scoutmaster brought a couple of 80cc Yamahas to a Scout weekend to watch the Big Bear Grand Prix races at Dead Man’s Point. “He let us go out and ride around on them,” Bill recalls. “I came home from that and I told my mother, ‘I’m going to get me a motorcycle’, and she said, ‘You’ll get a motorcycle over my dead body’. I told her I’d risk it.”

Author’s Note – Greg Williams:

Bill Getty is on to something by passing along motorcycles and providing mentorship to young people. In my case, I’ve known Griffin Smith, now 27, his entire life. When he was a youngster, I’d give him tin motorcycle wind-up toys. When he was 7, he and his dad came over to help unload a 1939 Triumph Speed Twin project without the forks. In his early teens we mechanically rebuilt an early D1 BSA Bantam, then, with his dad, a 1969 BMW R69S. He took a motorcycle training course, and then took his test aboard my 1972 Honda CB350. After completing a 1952 Triumph T100 bob job, I had Griffin put some miles on the bike. I was impressed with how he handled the machine, and thinking I’d leave the Triumph to him in my will, I quickly realized I’d rather see him riding the bike while I was still around to witness it.

The world in general needs more of his kind . A helluva lot more !

Great story about Bill. I’ve known him and his lovely wife for a number of years now and value our friendship. Bill wrote a series of stories for the Northern Ca BSA club newsletter that were always a hoot to read. I grew up in the same era and had a few of the same experiences but nothing like Bill. Now, with the old British motorcycle clubs apparently shrinking and most of us getting so grey, I commend Bill for his work with youth. I’d like to see more competing in clubs like AHRMA. It’s exciting to see a young guy or gal put down their cell phones and go out onto the track on a KTM or new Royal Enfield to compete.