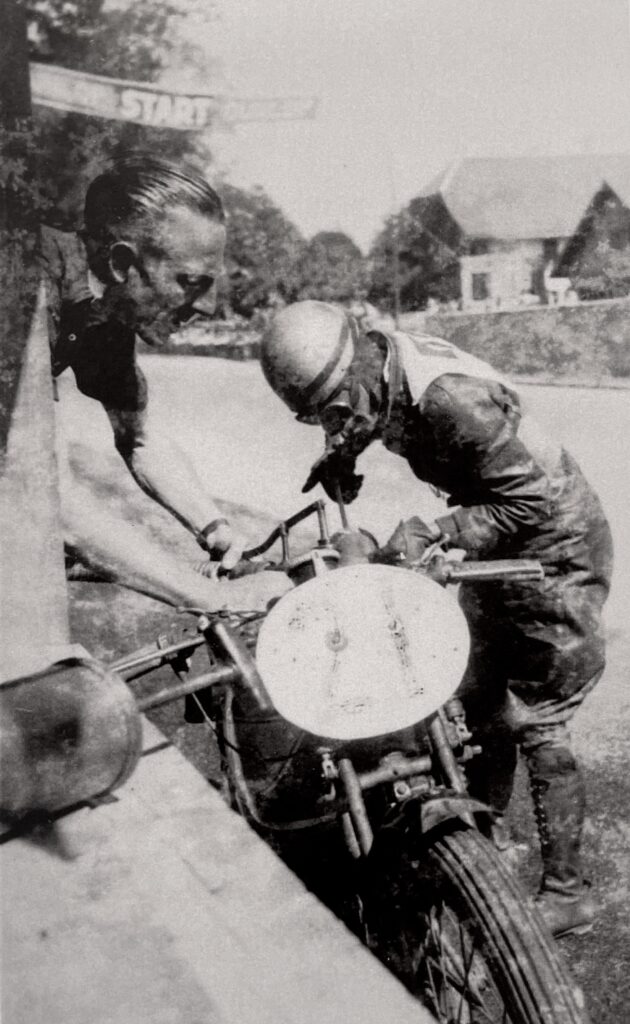

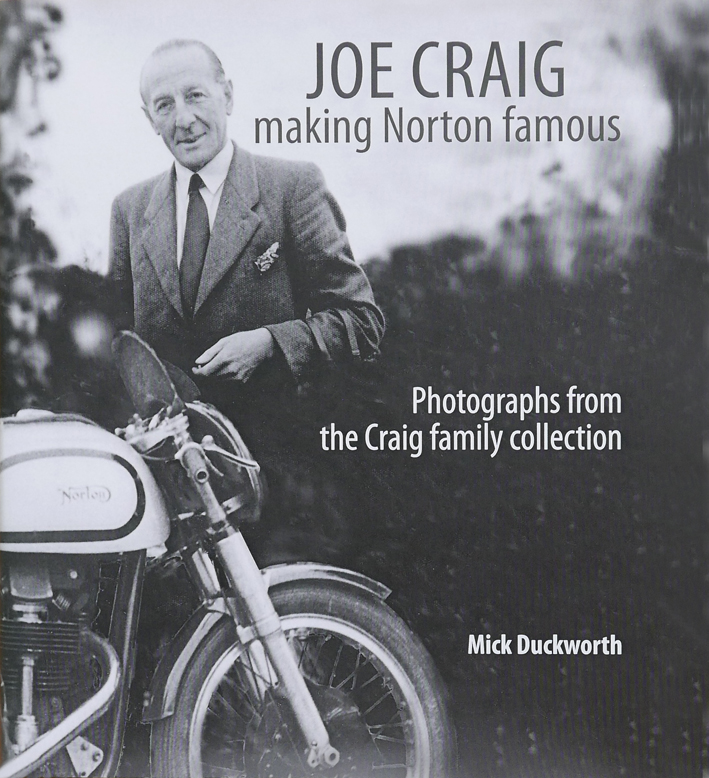

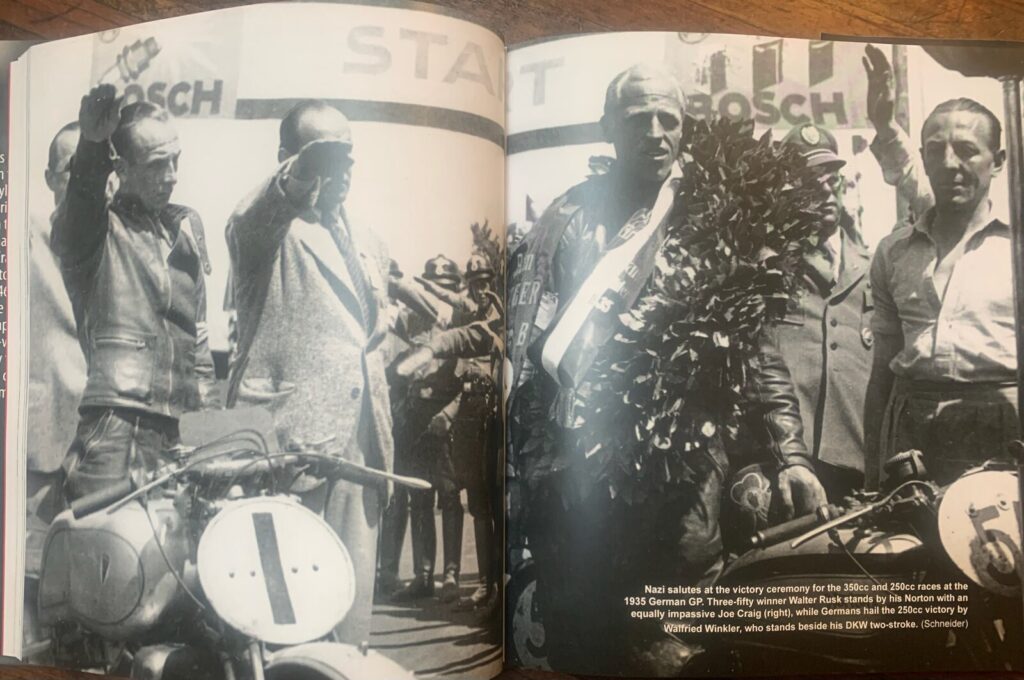

If any single person deserves credit for Norton’s extraordinary decades of racing dominance from 1930 through the mid-1950s, it must be Joe Craig. The de facto racing team manager for Norton under several owners, Craig at first successfully raced the factory product himself in the 1920s, then switched to the role of development engineer in 1930. He held that position (despite a break from the company during WW2) through 1955, when postwar company owners Associated Motor Cycles (AMC) decided exotic factory specials could no longer be supported financially, and focussed on selling factory catalogued racers like the Norton Manx, AJS 7R, and Matchless G50 models, all of which were produced simultaneously under their corporate ownership.

Related Posts

October 17, 2006

Those Dashing Racers of the 1920s: Harry Weslake

Harry Weslake was a snappy dresser, and…

Ahhhh … good ole ‘ snortin ” Norton … a legend ( of sorts.. and mainly in the UK ) in its own time .

Too bad the modern iteration leaves much to be desired

… but on the plus side … Norton frames and their reproductions ( specifically the ‘ Featherbed ‘ ) made for some of the best cafe racers and hot rod bikes ever … e.g.

Tritons

Norley’s ( H-D powered ,,, and yeah I know todays clueless hipsters and snowflakes want to call them something else … but Norley is the moniker .. so deal with it ) ….

… and the very best of the best … the Vincent V-Twin powered ..Norvin

Not to mention an argument can be made that Egli’s frames were directly influenced by the Norton ‘ Featherbed ‘

😎