The label ‘artist’ is tossed around lightly these days, for which we can blame Marcel Duchamp – but he had his reasons. Anyone building an aesthetically pleasing custom motorcycle gets an A in this post-‘Art of the Motorcycle’ world, but if a good custom doesn’t deserve a museum slot, what does? Still, the realm of aesthetics is not necessarily the realm of art, and a talented stylist with bodywork and paint doesn’t necessarily see the world through the strange prism of an artist. That’s not a put down; the world needs good design – it makes life better. But natural born artists are weird; they do what they do because they’re compelled to. Lucky for us, some artists stick their hands in design with remarkable results; for example, Paul Cox.

And then there’s the question of fame (or notoriety); some artists get famous, most labor in obscurity. Paul Cox hasn’t shunned the spotlight, but he certainly hasn’t had his due, which is partly due to honest humility, and partly the company he’s kept on his journey as an artist-craftsman. Cox rose to visibility in the late 1990s beside his friend Larry DeSmedt, who burned very brightly as the consummate showman Indian Larry. It was easy to misunderstand Paul Cox and Keino Sasaki’s role at Indian Larry Enterprises, given Larry’s charisma, and his fully reciprocated love for the camera. But anyone who’s seen Paul Cox’s work understands his past contributions, and the incredible range of his talents, from painting on canvas, making knives from Damascus steel, tooling the finest leather seats anywhere, and building kickass NYC-style choppers.

Growing up in the late 1960s and early ‘70s, Cox painted and drew as kids tend to, but not many children copy the paintings on their grandparents’ walls. “That was my first body of work – my grandmother would buy them for a dollar, which planted the idea of making a living as an artist.” Mid-‘70s choppers and Bicentennial graphics inspired him to create extended-fork bicycles, which soon progressed to minibikes, and making boats and hang gliders; “Basically anything I could make into a moving contraption.” After attending VCU (Virginia Commonwealth University School of the Arts), Cox moved to New York City (1988). He landed a job in commercial illustration; “I had a ton of work printed in newspapers and magazines, and was making art paintings at home. That lasted two years, until I got sick of advertising illustration.” He started modifying a Yamaha XS650 and a couple of Triumphs; friends soon wanted bikes built for them too.

For a Lower East Side biker, the center of the 1990s universe was Hugh Mackie’s 6th Street Specials. “A lot of my bike world connections were made and grew there, with Hugh and Dimi. They were the first shop to pay me to make a seat; they’d just opened, and it was a high energy scene, really raw, and really a blast.” Paul met Larry DeSmedt at 6th Street, and the pair clicked. By 1992, both worked at the new Psycho Cycles, Larry fabricating and mechanicking, and Paul doing leatherwork and fabrication. “That’s when things really took off. Steg and Frank and Larry and I made up our tight group, but it was my relationship with Larry that was truly inspirational.”

The 1990s chopper scene was volatile and hand-to-mouth, and when Psycho Cycles closed around ’98, Larry built bikes in a little garage below his apartment; “He was totally thrilled doing that, no strings attached, he could walk downstairs in his flip flops and underwear, it was perfect for him.” Hugh Mackie offered Cox space inside 6th St Specials for his leather and fabrication. “I owe so much to Hugh in so many different ways. He’s just a humble soft spoken guy, and it’s easy to pass him over because he’s so laid back, but how much he meant to me coming up in this scene gets glossed over, because there are so many other colorful characters.”

Indian Larry was primary among those; in 2000, he, Paul and other artisans leased a 5000 sq/ft warehouse on North 14th Street in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. “That’s the space everybody knows, it was one-stop shopping,” laughs Cox. With Keino Sasaki as a mechanic, the shop was re-branded Indian Larry Enterprises. Bobby and Elisa Seeger came on board to manage branding and merchandising and help run the show. The world spun faster when Jesse James invited Larry on his Motorcycle Mania TV show, which brought Indian Larry into the mainstream. “We’d done a lot of film work previously as ‘biker gang guys’ – you’d show up and get $100. Larry really dug that, and did it whenever he could. Motorcycle Mania was right up his alley. Like Ed Roth, Indian Larry was his own finest work of art; he created himself, and wanted to be a showman.” Before the Internet, TV exposure was gold, and people were floored by Indian Larry’s charisma. “He was a real guy, times 10. The world connected with him. It was all going well in 2002/3/4, and Bobby and Elisa really worked with him to keep things on track.”

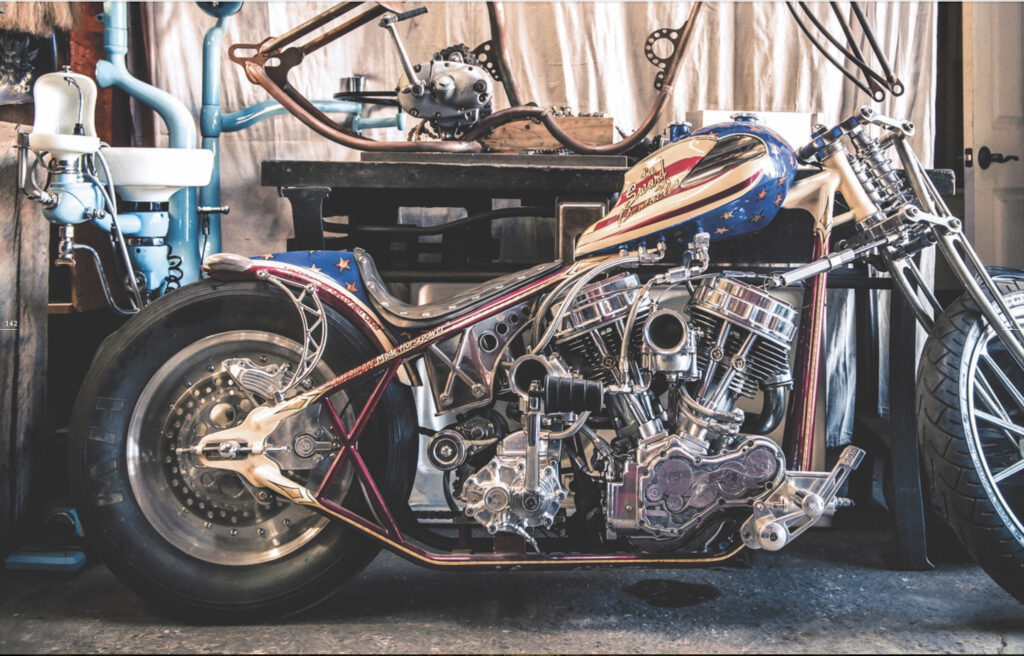

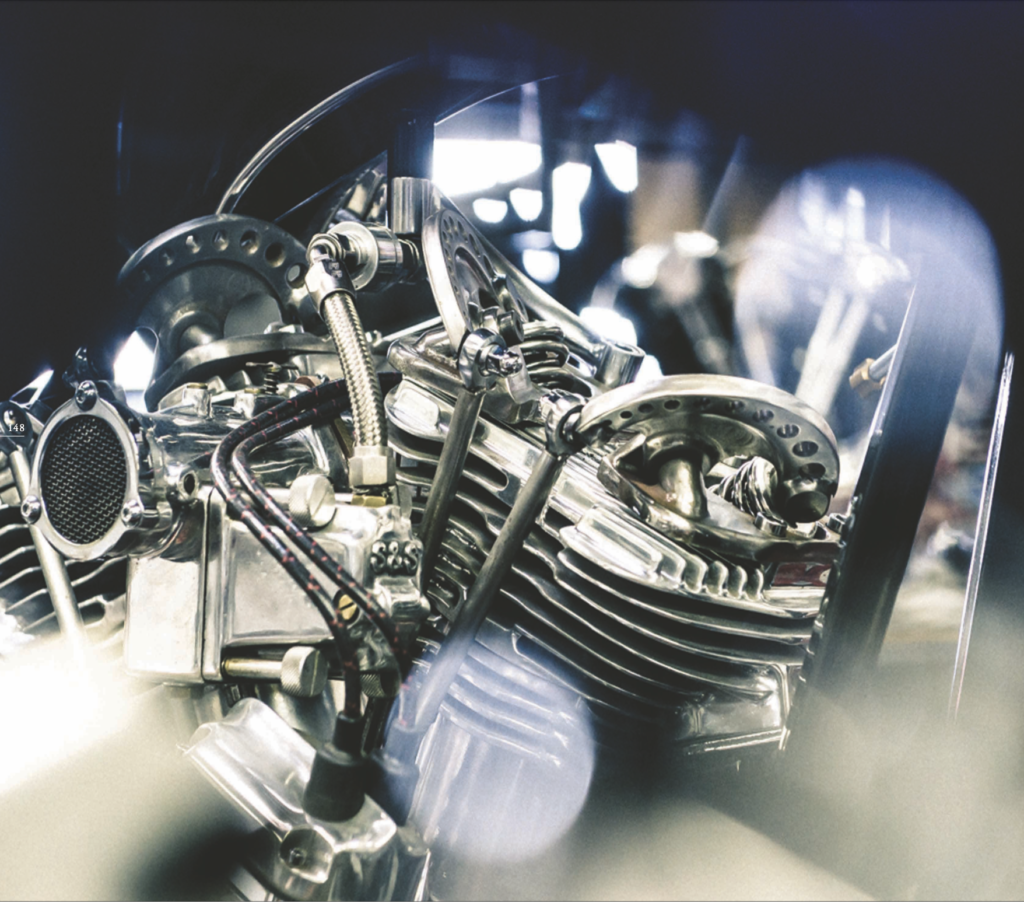

When Larry left this world on August 30th 2004, the outpouring of emotion convinced Paul, Keino, Bobby, and Elisa to change the shop to Indian Larry Legacy. “We thought we had to carry on what we’d started together, what Larry had built, all that momentum, and not turn it off overnight. The industry was really amazing and accepting. We kept building bikes like we had, but kept moving forward in design ideas in the same niche NYC chopper style – that little hotrod Harley we’d always done, which I still do today. The style is based on where I ride, what I ride, and what inspires me.”

In 2007, Cox decided to branch out. “It was a delicate time, but whatever I was doing creatively, I wanted to do professionally. That’s why my shop is Paul Cox Industries, not Paul Cox Choppers – it’s more about a creative lifestyle. I might look at architecture or furniture, and bring those ideas into leather or knives or bikes. I’m coming full circle to painting again, getting into a kind of pure art instead of only the ‘high performance art’, as I call my chopper work. Painting gets me excited, and influences my other work, and it all plays against each other. For me, painting, leather, and metalwork are always happening at the same time. My shop is set up in zones; there are people who are interested in certain aspects of what I do, who may not know the other things I do!”

[This article originally appeared in the inaugural issue of 1903 magazine, in 2016]

OK folks … lets put the Art vs Craft argument to rest once and for all … and ( bleep ) Duchamp and all his self serving revisionist definitions !

ALL art is craft . But not all craft is art !

In order for CRAFT to be elevated to the status of ART … it must be in some way original .. ground breaking … not to mention over the course of time … influential

So … by that definition ( the ONLY definition that counts) …. in todays custom M/C world who can be considered ART?

Hmm … for one … Shinya Kimura comes to mind right off the bat

( so many of todays custom builders including the likes of Max Hazan [ a personal favorite )]have been influenced by Shinya’s bikes ,,, despite the majority of them being unwilling to admit it … not to mention the press ignoring it … its … ludicrous )

So … in light of the above .. can Mr Cox be considered an ARTIST ?

Lets see now … damn fine bikes mind you …. but a bit too … errr … influenced ( by the past … in fact his bikes all could of been built in the 60’s 70’s ) … rather than influencing … from the photos though his craft seems to be top drawer … so ..

Artist ? Nope …. one damn fine craftsman who’s work someday assuming he can find his own ‘ voice ‘ might just wind uo being elevated to the status of ART ?

Damn right ! Damn fine bikes .. damn fine craftsmanship …. but not art … yet .

To be clear though …. I’m loving Mr Cox’s bikes … they jes aint to the level of art … yet … no insult intended or implied

FYI’ In case anyone’s wondering …. I consider myself a ‘ craftsman ‘ who some of my craft has found its way into the hallowed halls of ART

😎

PS; Yes I’m a bit of an elitist … and mighty damn fine proud of it …