[Originally published in The Automobile magazine. For a copy of the Sept. 2024 issue, click here]

The need for Art is surely older than the need for Speed, and painted evidence of nomadic artisans afoot chasing down game 30,000 years ago remains as testament to a hard life without wheels. Or perhaps, the possibility of art was available, while speed per se had to wait for the taming of the horse. When the wheel finally arrived, it was immediately decorated; carts and chariots became a canvas for expression – personal or divine. When the automobile appeared, the tradition of horse-drawn coachbuilding carried on, because looking smart in your wheels has always been a priority. Some of that work is exquisite, but is it art? That’s a sticking point, as battle lines were drawn in 19th Century French académies between the ‘Fine Art’ versus ‘Craft’ and ‘Decoration’. That line is finally dissolving, as artists expand their oeuvre from painting or sculpture to include design. For example, the fake Donald Judd dining set crassly shown off by Kim Kardashian, that earned her a lawsuit from Judd’s estate. Since everyone is an artist these days (per Marcel Duchamp), how do we differentiate between art hobbyists decorating their cars, and famous artists being commissioned to decorate cars?

There is a difference between ‘art cars’ and Art Cars. One is a thriving and popular form of expression using vehicles as an artistic medium, practiced the world over since the origin of the wheel. The umbrella term ‘art car’ thus includes many important genres, like the ‘custom culture’ car scene originating in the late 1940s, the historically deep Low Rider scene in the USA, the insane Indonesian Vespa cult (where through metal mitosis scooters are transformed into 20- or 30-wheeled living platforms), as well as the psychedelic vehicles emerging in the 1960s. Hippie cars lingered and became the so-called ‘art car’ movement, as documented by Harrod Blank in the 1992 film Wild Wheels, and the 1997 book ‘Art Cars’ (Ineri Foundation). Blank co-founded the Art Car Fest, with art car parades became a thing in the US; in India there’s the Cartist festival, with extravagant lorries assaulting all the senses, all at once. There’s even an Art Car Manifesto (1997, James Haritas), a must for any popular art movement: “The art car is… transforming the automobile into a potent new personal symbol.” In sum, the art car movement is enormous, popular, and global. But I’m not addressing any of those scenes here, which in retrospect make the Art Car movement look very small, and very elitist. Which it is.

But the first BMW Art Car of 1975 was not the origin of the Art Car genre: that was created 50 years earlier, in Paris. How Sonia Delaunay was tailor-made for the invention of the Art Car requires an understanding of her significance as a pioneering artist of multiple mediums. That she oversaw not one but three Art Cars over a 50-year span makes her a titan of the movement. Her work is so strongly identified with Art Cars that cars by other designers have been mis-attributed as Delaunays…especially when the automobile brand is Delaunay, but we’ll get to that.

Sonia Delaunay was born Sofia Stern in Odessa (1885) to poor Jewish parents, and was orphaned by age 5. She was adopted by her wealthy and childless uncle Henri Terk of St. Petersburg, and re-dubbed Sonia Terk. At 16, a teacher noted her artistic brilliance, so she was sent to the Academy of Fine Arts in Karlsruhe, Germany. In 1905 she convinced her adoptive parents to allow her to study at the Académie de La Palette in Paris for a summer. Paris was the center of the artistic universe, and she begged to return. The Terks wanted her in Russia and married, at which point she could take her inheritance; two apartment buildings in St. Petersburg providing ample income.

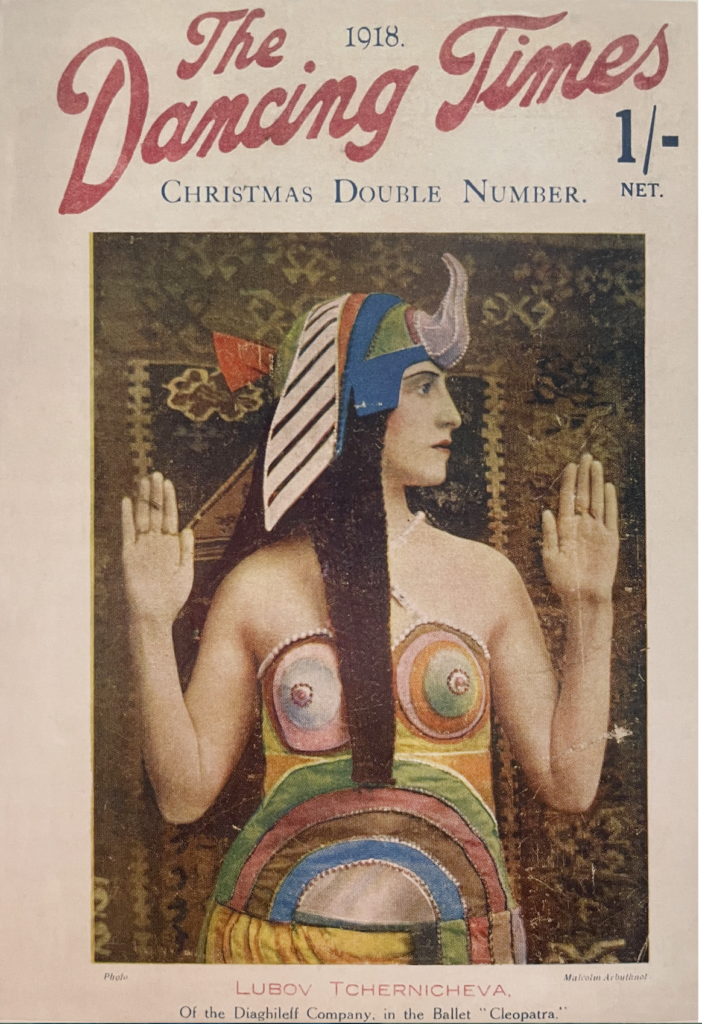

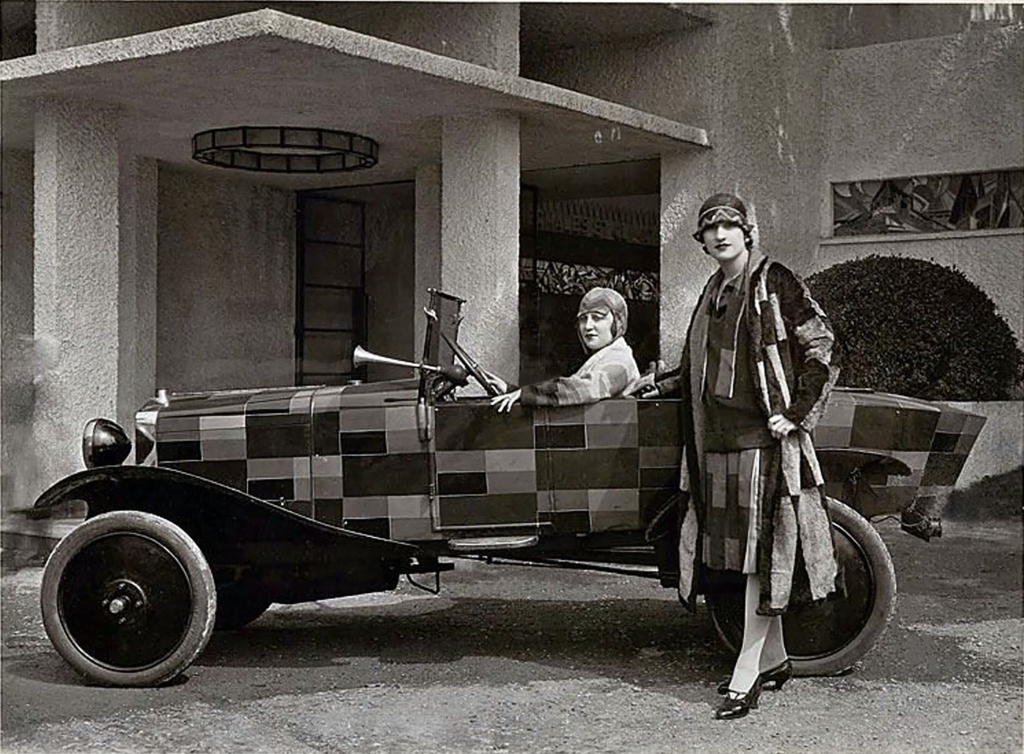

Maison Sonia boomed as a frenetic postwar spirit spilled over into modern art, design and decoration. In 1924/5, journalist Maurice Kaplan begged her friend Sonia Delaunay to apply one of her abstract designs to Kaplan’s charming new runabout, an Ariés 5-8hp Torpedo 3-seat boat-tail convertible. Sonia provided a pattern of rectangular color blocks in green, gray and black, in the mode of her copyrighted Simultané fabrics. Sonia was at this time financial partners with Jacques Heim, who invested 500,000 francs to establish Ateliers Simultanés – a nod to the Delaunays’ art theory – as a storefront studio, with Sonia-designed fabrics, knitwear, furs, handbags, scarves, and shoes, all of which were a runaway success. Her bold abstract patterns were particularly suited to the fashions of the 1920s, as their lack of waistline and minimal tailoring were suitable for any body size or shape, a concept familiar today to fans of Comme des Garçons or Marni. Sonia even produced special clothing for automobilists and their passengers, and surviving examples include a set of four embroidered cloche hats for the daughters of her friends Jean and Annette Coutrot.

The Art Car as an idea

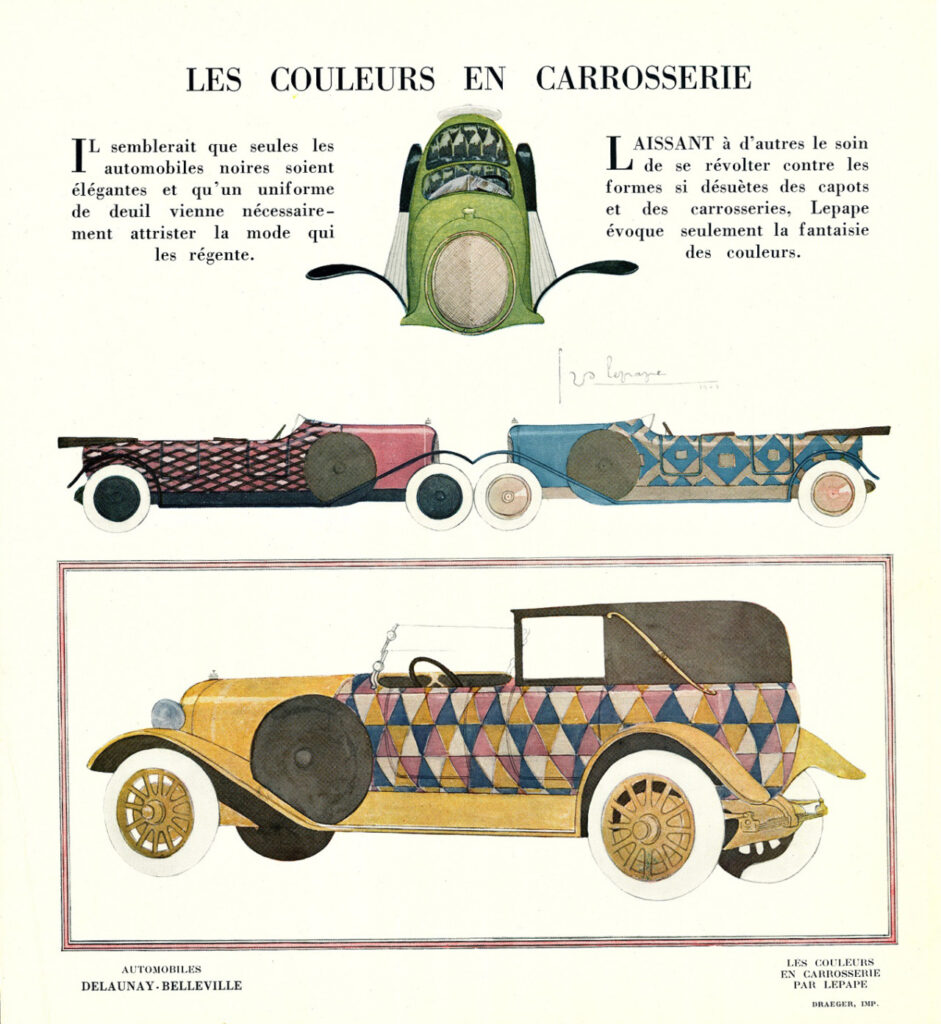

There was a contemporary context for Sonia’s Art Car in the aesthetic tumult of Art Deco Paris: the idea of an automobile painted with abstract patterns was already afoot. In 1923 the luxury automobile brand Delaunay-Belleville, est. 1904 by Louis Delaunay (whose unrelated surname sowed much confusion later), commissioned five well-known graphic artists to paint sample color schemes for cars, as an ‘essai sur les differentes manières de les carrosier’. The artists included Georges Lepape, Eduardo Garcia Benito, René Lelong, Jacques-Emile Ruhlmann, and Charles Martin. The resulting catalogue is exquisite and beautifully printed by Draeger in Paris (still in business). The proposed paint schemes are exuberantly Art Deco, and remarkably similar to each other, all using abstract geometric patterns in multiple colors. To my knowledge no customer ever actually ordered such a car, but even as an ‘ideal’ concept (so popular in the 20th Century motor magazines), such color applications were perhaps too flambouyant for the average wealthy automobilist.

The 1920s were great financially for the Delaunays, but not the ‘30s. When the Crash hit Europe in 1930, the high-end fashion business dried up. The decision to close Atelier Simultanés meant she had to lay off 30 workers, and give up their apartment. Once again they were poor artists relying on Sonia’s ingenuity to survive, but she called the mid-to-late 1930s her ‘freedom years,’ without the pressure of a fashion line, storefront, or employees. She still designed fabrics for Jacques Heim, took on interior design and graphic art jobs, and painted. For the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques, she and Robert both got commissions for enormous murals, which was a shot in the arm.

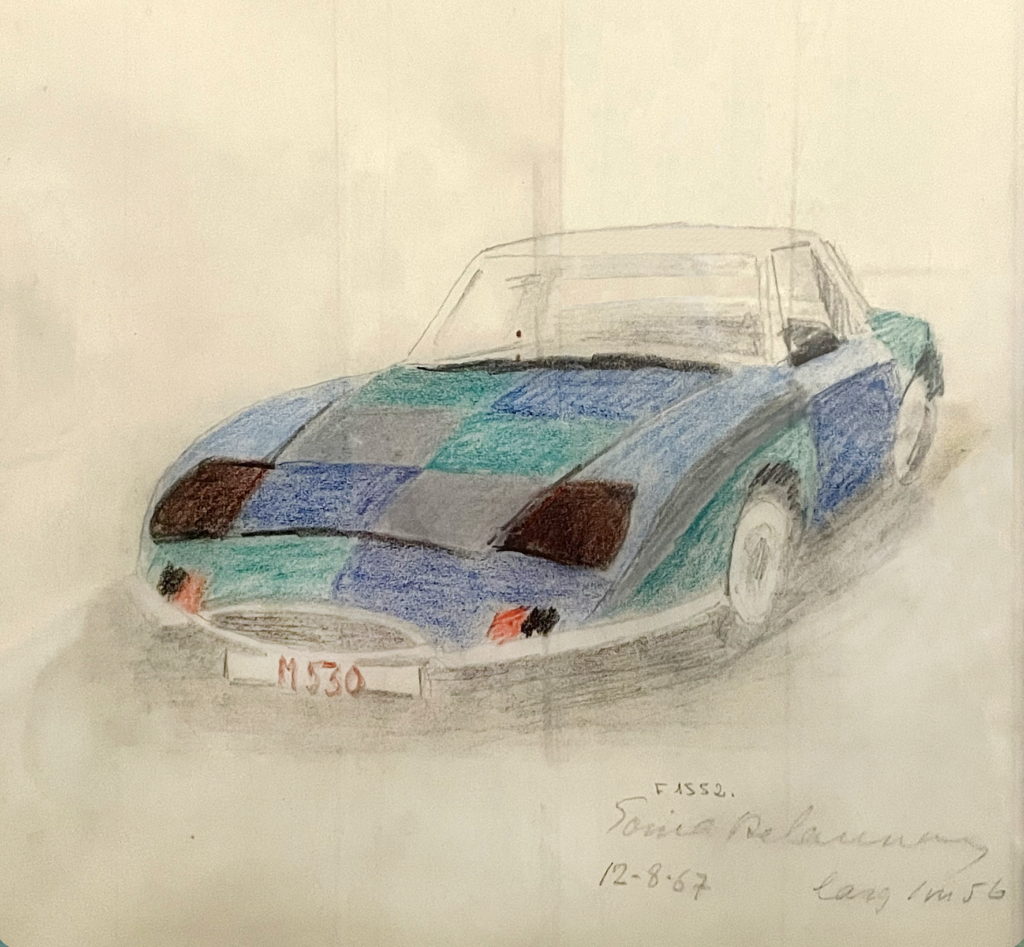

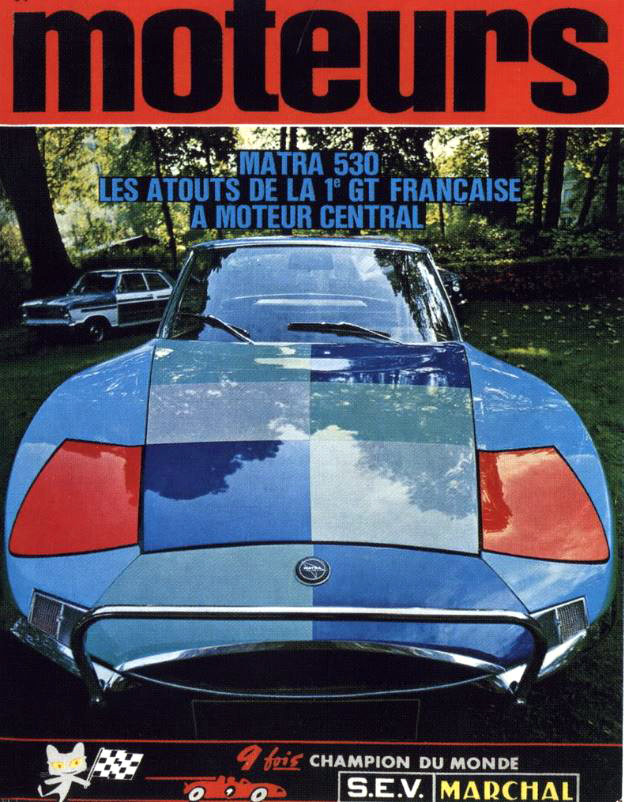

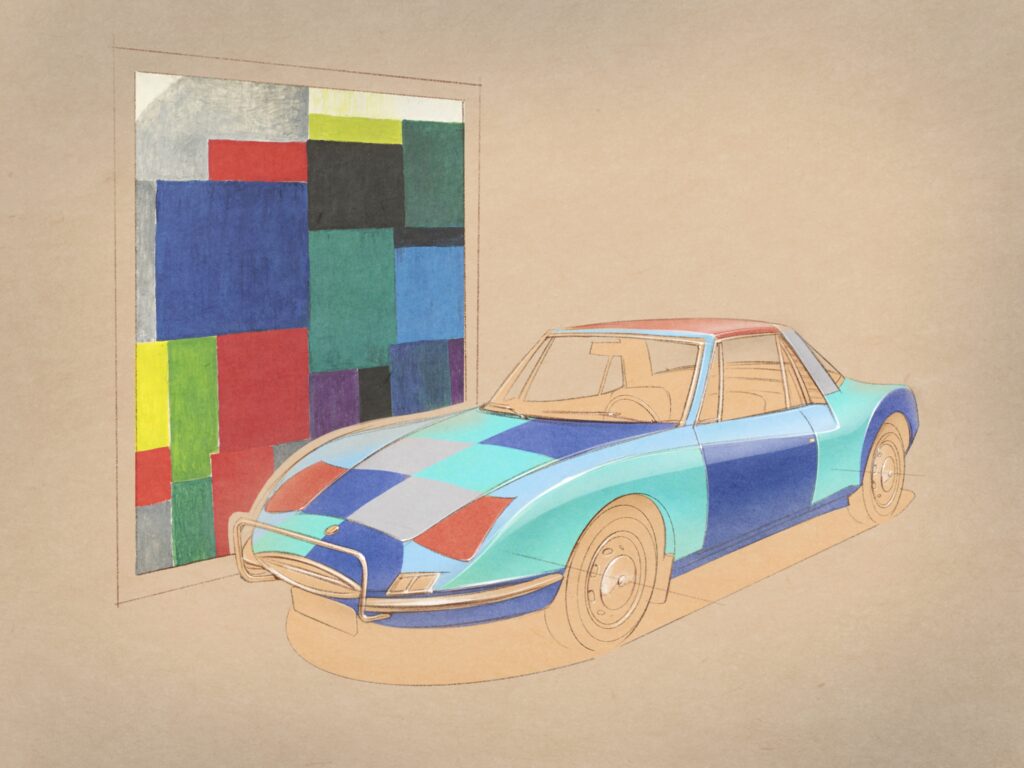

In an echo of the 1924 Delaunay-Belleville Art Car pamphlet, in early 1967 Sonia Delaunay was chosen for an exhibition of artist-decorated cars entitled ‘Cinq voitures personnalisées par cinq artistes contemporains’ (five cars personalized by five contemporary artists), organized by the arts and culture magazine Réalités. The cars were to be auctioned off as a fundraiser for the Fondation pour la recherche médicale. Four of the artists were pioneers of the Op Art style emerging in the 1960s, including Victory Vasarély, whose bulging dot paintings were the dilated-pupil grandchildren of the Delaunays’ discs. But without Sonia’s decades of design work under his belt, Vasarely’s strips of reflective mylar dots randomly applied to an Opel Kadett are simply – there is no other word for it – awful. The artist Arman (Armand Fernandez) covered a 1961 Renault 4L with 819 decals of…a Renault 4L. “The 819 Renaults lined up on the body symbolise the theme of accumulation.” Indeed. Carlos Cruz-Diez transformed a Daf 33 into a ‘Physichromobile’, using carefully measured vertical lines of different colors on both the bodywork and windows, arranged to produce visual after-effects in the viewer’s eyes. Yaacov Agam’s work was simplier, with his Simca 1000 featuring large, simple blocks of color, and was the most appealing of the younger artists’ work for the auction. Yet it was the 81-year old Sonia Delaunay who stole the show, and created an enduring work of art – her second Art Car.

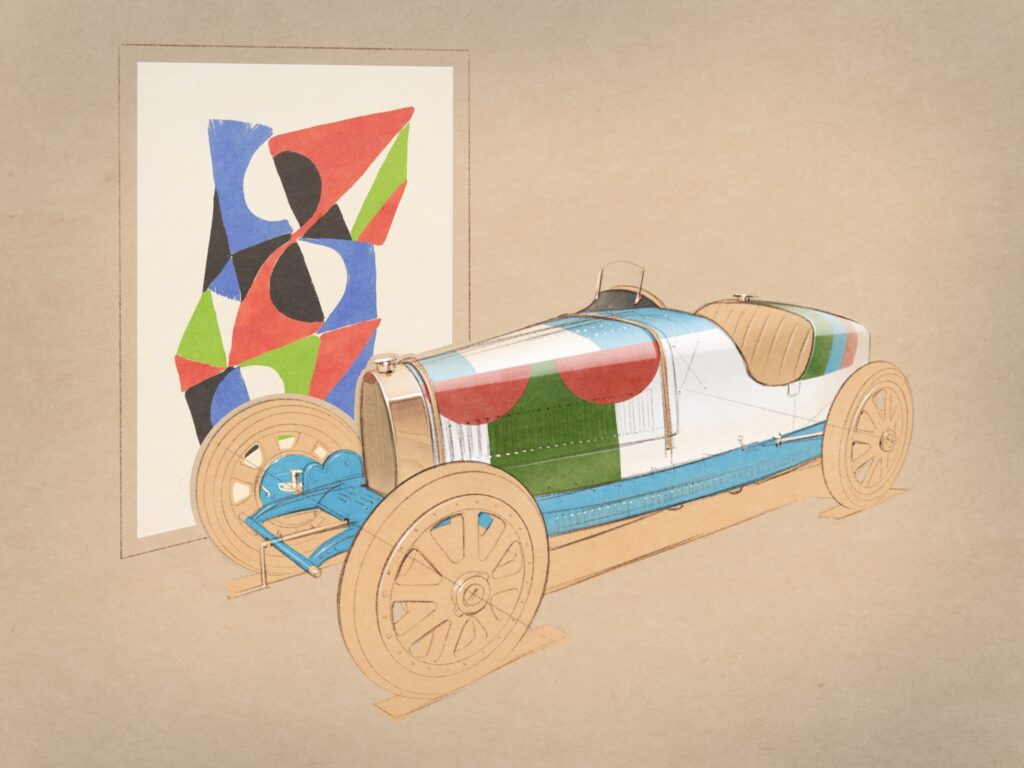

In 1973, Sonia – nearly 90 – was again invited to create a color scheme for a car, in this case a Bugatti T35, supplied to her as a 1:8 scale model by Jean-Paul Fontenelle. The model would be sold at auction to benefit the Bal des petits lits blancs, a children’s hospital charity, and had been organized by Artcurial and Hervé Poulain. The Bugatti T35 was an inspired choice as the perfect 1920s canvas for Sonia’s artwork, and her concept was arguably the best of her three Art Cars, with its colors arranged in bold, colorful roundels against blocks of color in blue, white, red, and green, very much in line with her graphic work over the previous 20 years. The model would have remained just that, a mock-up, had not the imaginative owner of an actual Bugatti T35, Marc Nicolosi, been inspired to make it real. Nicolosi asked his friend Hervé Poulain for permission from Sonia Delaunay to use the color scheme on his car. Her consent is preserved by the Nicolosi family in a letter of 3 October 1977: “I put one condition on this agreement, which is that the production be submitted to me before the words ‘after Sonia Delaunay’ are added.” Marc’s son Baptiste Nicolosi continues the tale: “Sadly, my father did not paint the Bugatti in the 1970s, and Sonia died soon after (1979). At the beginning of the 1990s he still wanted to do the paint scheme, so he contacted the owner of the model, asking ‘can you loan me the model so that I copy the paint scheme?’ He said yes, but we could keep the paint scheme ‘only for five years’. We pushed it a little bit, like 6 or seven years, but in the end my father put it back to gray.”

Chalk up another one to the ladies ! Cause once again one of them beat us ( men folks ) to the punch !

Damn fine article .. damn fine choice of photos as well …

Now if only someone ( is ya listening CMC … AutoArt .. MiniChamps etc ) would make and sell a 1/18 or 1/12 scale model of that Bugatti Type 35 ( my favorite car of all time ) she created . Cause that … is a winner on all fronts . Ahhh .. but the Matra … should of done something like that to my Bagheera back when I resided in Nice … damn .. a missed opportunity indeed ,..

.. wished I’d of know about her and her work earlier !

And again … thanks PdO … let me know if you are aware of someone making that Type 35 of hers in a scale model …. hmmm ..

The only model I’ve seen of her T35 design was painted by hand, and fetched $7500 at auction in 2016. I reckon her original would be 20x that or more…: https://cars.bonhams.com/auction/23591/lot/9/a-18-scale-model-of-the-sonia-delaunay-decorated-bugatti-type-35-by-p-fontenelle-3/

Sooooo …. hmmmm … a blue CMC 1/18 Type 35 ( like the one in the lead photo ) $600 + dollars … a few bottles of paint .. $20 maybe … some fine graded sandpaper .. couple a bucks …. couple a quality brushes maybe another $20 .. and some practice on paper afer hand … yup … bet I can do that with some additional photos .

Or .. alternatively … I could has me self a mid life crisis … spend a small portion o’ that pot o’ beans we gots saved up .. by myself a Pur – Sang re-creation from Argentina .. new our used .. and have at it with a local custom painter I know ….. hmmmmmm ….

Options options options galore … so I’ll skip hers and the original model … for that much I could create another ten … selling the additional for …. hmmm … say …. $2K + each ?

Ahhh … DIY …. beats the hell outta the market place every time !

😎

Sure, and you can digitally print any Van Gogh, CNC any motorcycle design. Have you seen what they are doing with reproducing stone sculptures these days? You can have a perfect ‘David’ in your 500 square foot garden. You are missing the point of originality. The hands and the minds of the people who are creating these works, leave their souls in the pieces we admire, and yes covet. Most of these creations fail and are ridiculed and the exposed artist is shattered. We are living in soul less times. That’s why you think a DYI project is the same as an original. It’s not. I build and restore motorcycles. I can make a perfect replica of a Ducati TT1/2, down to every last detail. I know this because I own 4 original racers that were built by Giorgio Nepoti, Rino Carracci, Fabio Taglionio, and Franco Farne. These artists are all gone, but the soul and essence of the men are still in these machines, I feel, and see them everyday. It is a tangible thing for me. Original is still original. There is a difference. More importantly, it’s not about the money. The people that treat art as a commodity are missing the point of the artist’s vision. I am not naive,I know some paint and create for money. I prefer art for the sake of art. The value is in the love and inspiration I have, and get, from my rolling and functioning original art. I can look at them all day. They are my catalyst to create and help find my soul.

Couldn’t agree with you more . Not reproductions being sold as reproductions …. but fakes and forgeries galore being sold as the real thing .

A reproduction of something ? I can live with . After all being a musician what is a recording of my music or a performance by someone else other than a reproduction of the original ?

[ bet ye never considered that one while downloading left and right… in essence legally stealing from the composer / copyright holder … did ya ? ]

But fakes and forgeries ? Hmmm … to be honest in this insane world of art ( most of which is barely artifice ) as a commodity ? In all honesty I’ve got mixed feelings .. on one hand … I hate seeing a masters work turned out by a forger being sold as the real thing …. but on the other …. well … if Mr or Ms/Mrs More Money than Brains is stupid enough to pay a godawful fortune for a fake without doing due diligence …. hmmm … part of says they’r getting exactly what they deserve !

One last thought on the subject of F&F’s … these days with the extreme prices of collector and hyper cars … even automobiles and motorcycles( new as well as classics ) are being forged sold for millions .

For instance . That legitimate sub $200k re-creation of a Bugatti Type 35 by Pur Sang I mentioned ? Like to take a guess how many documented cases there are of those wonderful re-creations being passed off as the real thing ? At least 40 that I know of . Several of which have made the news worldwide ( here in the US nobody other than the fool that bought one as the real thing could care less )